Fungi are a diverse group of organisms that reproduce through various methods, one of which involves the production of spores. The question of whether fungi produce spores during meiosis is central to understanding their reproductive biology. Meiosis is a specialized type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid cells, which is crucial for sexual reproduction. In fungi, meiosis typically occurs in structures like sporangia or asci, leading to the formation of spores such as ascospores or basidiospores. These spores are often the result of sexual reproduction and are dispersed to initiate new fungal colonies. Therefore, while not all fungal spores are produced during meiosis, many sexually derived spores are indeed a product of this process, highlighting its significance in fungal life cycles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do fungi produce spores during meiosis? | Yes |

| Type of spores produced | Meiospores (haploid spores) |

| Examples of meiospores | Ascospores (in Ascomycetes), Basidiospores (in Basidiomycetes), Zygospores (in Zygomycetes), and Oospores (in Oomycetes) |

| Function of meiospores | Sexual reproduction, genetic diversity, and dispersal |

| Process of spore formation | Meiosis followed by sporulation (development of spores) |

| Ploidy of spores | Haploid (n) |

| Ploidy of parent cells | Diploid (2n) in most fungi, except for some groups like Zygomycetes |

| Significance of meiosis | Reduces chromosome number, promotes genetic recombination, and generates diversity |

| Examples of fungi producing meiospores | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast), Penicillium, Aspergillus, and mushrooms |

| Exceptions | Some fungi, like certain yeasts, can reproduce asexually without meiosis, but sexual reproduction still involves meiosis in most cases |

| Latest research (as of 2023) | Studies continue to explore the molecular mechanisms of meiosis and sporulation in various fungal species, with advancements in genomics and transcriptomics providing new insights into these processes |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fungal Meiosis Process: Overview of meiosis in fungi, highlighting unique stages compared to other organisms

- Sporulation Mechanisms: How fungi form spores during meiosis, including ascospores and basidiospores

- Genetic Diversity: Role of meiosis in creating genetic variation through recombination in fungal populations

- Environmental Triggers: Factors like nutrient availability and stress that induce spore production in fungi

- Types of Fungal Spores: Classification of spores (e.g., zygospores, conidia) produced during meiosis

Fungal Meiosis Process: Overview of meiosis in fungi, highlighting unique stages compared to other organisms

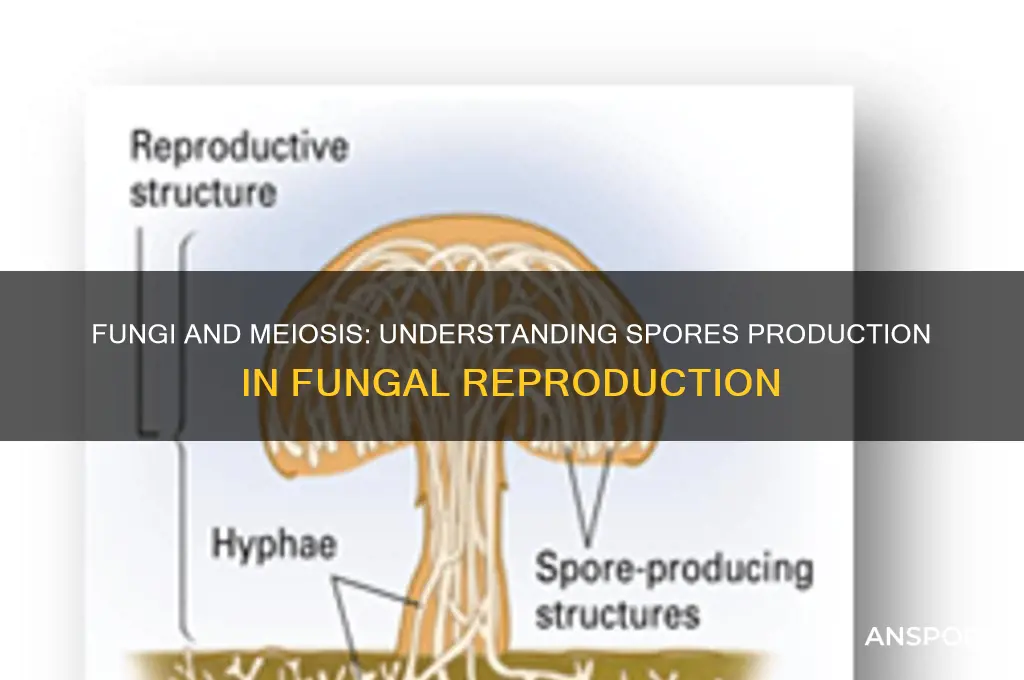

Fungi, unlike animals and plants, undergo a distinct meiotic process that is intricately tied to their life cycle and spore production. Meiosis in fungi is not merely a mechanism for genetic diversity but a critical step in their reproductive strategy. While the fundamental principles of meiosis—chromosome replication, recombination, and reduction—remain consistent across eukaryotes, fungi exhibit unique stages and adaptations that reflect their ecological roles and evolutionary history.

One of the most striking features of fungal meiosis is its integration with sporulation. In fungi, meiosis is not an isolated event but is directly coupled with the formation of spores, which serve as both reproductive units and survival structures. For example, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast), meiosis culminates in the production of four haploid spores enclosed within an ascus. This process is highly regulated, with specific checkpoints ensuring that spore formation only occurs under conditions favorable for survival and dispersal. Unlike animals, where meiosis produces gametes that must later fuse, fungal spores are self-contained units ready for immediate dispersal, highlighting a key divergence in reproductive strategies.

Another unique aspect of fungal meiosis is the variability in its timing and triggers. In many fungi, meiosis is induced by environmental cues such as nutrient depletion or changes in temperature, rather than being a continuous part of the life cycle. For instance, in *Neurospora crassa*, a model filamentous fungus, meiosis is triggered by starvation conditions, leading to the formation of ascospores. This adaptability allows fungi to synchronize their reproductive phases with environmental conditions, maximizing their chances of survival and propagation. In contrast, animals and plants often have more rigid schedules for meiosis, tied to developmental stages rather than external factors.

The structure and function of fungal meiotic cells also differ significantly from those of other organisms. In basidiomycetes, such as mushrooms, meiosis occurs in specialized structures called basidia, which produce external spores. This contrasts with the internal spore formation seen in ascomycetes. Additionally, fungi often exhibit complex genetic recombination patterns during meiosis, including high rates of gene conversion and non-crossover events. These mechanisms enhance genetic diversity, which is crucial for fungi to adapt to diverse and often hostile environments.

Practical insights into fungal meiosis have significant implications for biotechnology and agriculture. Understanding the meiotic process in fungi like *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium* can aid in the development of strains optimized for antibiotic or enzyme production. For example, manipulating meiotic recombination rates can accelerate the breeding of fungal strains with desirable traits. Similarly, in plant pathology, knowledge of fungal meiosis helps in designing strategies to control spore-borne diseases, such as wheat rust or powdery mildew, by disrupting key stages of the meiotic cycle.

In summary, the fungal meiosis process is a fascinating blend of conserved eukaryotic mechanisms and unique adaptations. Its integration with sporulation, responsiveness to environmental cues, and specialized cellular structures set it apart from meiosis in other organisms. By studying these unique features, scientists can unlock new applications in biotechnology and gain deeper insights into the evolutionary diversity of life.

Can You Safely Dispose of Fungal Spores Down the Drain?

You may want to see also

Sporulation Mechanisms: How fungi form spores during meiosis, including ascospores and basidiospores

Fungi employ meiosis, a specialized cell division process, to generate genetically diverse spores, ensuring their survival and adaptation in changing environments. This mechanism is particularly evident in the formation of ascospores and basidiospores, two distinct types of spores produced by different fungal groups. Understanding these sporulation mechanisms provides insights into fungal reproduction and highlights the intricate strategies fungi use to propagate.

The Ascospore Journey: A Sac-Enclosed Adventure

In Ascomycota, the largest fungal phylum, meiosis occurs within a sac-like structure called the ascus. Here's a breakdown:

- Dikaryotic Prelude: Two haploid nuclei fuse within the ascus, forming a diploid nucleus.

- Meiosis I & II: This diploid nucleus undergoes meiosis I and II, resulting in four haploid nuclei.

- Ascospore Formation: Each nucleus is then packaged into a spore, forming eight ascospores within the ascus.

- Release and Dispersal: The mature ascus ruptures, releasing the ascospores, which are dispersed by wind, water, or animals.

Basidiospore Ballet: A Club-Like Performance

Basidiomycota, another major fungal phylum, takes a different approach with basidiospores.

- Club-Shaped Basidium: Meiosis occurs on a club-shaped structure called the basidium.

- Nuclear Migration: Four haploid nuclei migrate to the tips of the basidium.

- Basidiospore Development: Each nucleus develops into a basidiospore, typically four per basidium.

- Ballistospore Discharge: In many species, basidiospores are forcibly discharged, reaching distances of up to several millimeters, aided by a droplet of fluid that forms at the spore's base.

Comparative Analysis: Ascospores vs. Basidiospores

While both ascospores and basidiospores result from meiosis, their formation and dispersal strategies differ significantly. Ascospores are enclosed within a protective ascus, offering some shelter during development and dispersal. Basidiospores, on the other hand, are exposed on the basidium, relying on ballistic discharge for efficient dispersal.

Unveiling the Truth: Does Moss Have Spores and How Do They Spread?

You may want to see also

Genetic Diversity: Role of meiosis in creating genetic variation through recombination in fungal populations

Fungi, like many eukaryotic organisms, rely on meiosis to generate genetic diversity, a critical factor in their survival and adaptation. During meiosis, fungal cells undergo a specialized form of cell division that results in the production of haploid spores. These spores are not merely products of division but are also vehicles for genetic recombination, a process that shuffles genetic material between homologous chromosomes. This recombination is a cornerstone of genetic diversity, enabling fungal populations to respond to changing environments, resist pathogens, and exploit new ecological niches.

Consider the process of crossing over during prophase I of meiosis, where homologous chromosomes exchange segments of DNA. This mechanism introduces novel combinations of alleles, creating unique genetic profiles in the resulting spores. For instance, in the model fungus *Neurospora crassa*, crossing over occurs at an average rate of 1-2 events per chromosome pair, significantly increasing the potential for genetic variation. Such recombination is particularly vital in fungi, as many species alternate between haploid and diploid phases, with meiosis serving as the bridge between these phases. The haploid spores produced are not only genetically diverse but also capable of dispersing over long distances, ensuring that this diversity is spread across populations.

To illustrate the practical implications, take the case of *Aspergillus nidulans*, a fungus widely studied for its genetic plasticity. Researchers have observed that increased recombination rates during meiosis correlate with enhanced resistance to fungicides in agricultural settings. By manipulating environmental conditions, such as temperature and nutrient availability, scientists can influence the frequency of crossing over, thereby modulating genetic diversity. For example, exposing *A. nidulans* to temperatures of 30°C during meiosis has been shown to increase recombination rates by up to 20%, leading to a higher proportion of spores with novel genetic traits.

However, the role of meiosis in fungal genetic diversity is not without challenges. In some fungi, such as *Candida albicans*, meiosis is rare or absent, and genetic variation arises primarily through parasexual cycles or mutagenesis. This highlights the importance of understanding the specific mechanisms driving diversity in different fungal species. For those fungi that do undergo meiosis, ensuring optimal conditions for recombination is crucial. Practical tips for researchers include maintaining cultures at specific humidity levels (e.g., 85-90% relative humidity for *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*) and providing nutrient-rich media to support robust meiotic processes.

In conclusion, meiosis plays a pivotal role in generating genetic diversity in fungal populations through recombination. By fostering unique genetic combinations, this process equips fungi with the adaptability needed to thrive in diverse environments. Whether in natural ecosystems or laboratory settings, understanding and manipulating meiotic recombination offers a powerful tool for studying fungal evolution and addressing practical challenges, such as fungicide resistance. For anyone working with fungi, recognizing the significance of meiosis in genetic variation is essential for both theoretical and applied research.

How Spores Shield Bacteria: Survival Strategies in Harsh Environments

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental Triggers: Factors like nutrient availability and stress that induce spore production in fungi

Fungi, unlike animals and plants, have evolved unique strategies to survive and propagate in diverse environments. One such strategy is the production of spores, which are often triggered by specific environmental conditions. Nutrient availability and stress are two critical factors that can induce spore production in fungi, ensuring their survival and dispersal in challenging habitats.

The Role of Nutrient Availability

Nutrient scarcity acts as a powerful signal for fungi to transition from vegetative growth to reproductive modes. For instance, when nitrogen levels drop below 10 mM in the substrate, species like *Aspergillus nidulans* initiate sporulation. This response is not merely a survival mechanism but a calculated adaptation. Fungi detect nutrient depletion through specialized receptors, such as the GprA protein in *A. nidulans*, which triggers signaling pathways leading to spore formation. Conversely, abundant nutrients, particularly carbon sources like glucose at concentrations above 2% (w/v), often suppress sporulation, favoring hyphal growth instead. This nutrient-dependent switch highlights how fungi prioritize resource allocation based on environmental cues.

Stress as a Catalyst for Sporulation

Environmental stresses, including desiccation, temperature extremes, and oxidative damage, also induce spore production. For example, exposure to temperatures above 37°C in thermotolerant fungi like *Candida albicans* triggers the formation of chlamydospores, thick-walled structures resistant to harsh conditions. Similarly, osmotic stress, such as high salt concentrations (e.g., 1 M NaCl), prompts spore formation in *Neurospora crassa* by activating the MAP kinase pathway. These stress-induced spores are not just survival units but also dispersal agents, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats once conditions improve.

Practical Implications and Manipulation

Understanding these environmental triggers has practical applications in agriculture, biotechnology, and medicine. For instance, controlling nutrient levels in fungal fermentation processes can optimize spore yield for industrial enzyme production. In agriculture, manipulating soil nutrient content can suppress pathogenic fungi by preventing sporulation. Conversely, inducing spore formation in beneficial fungi, such as mycorrhizal species, can enhance plant growth under nutrient-poor conditions. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, maintaining a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 40:1 in substrates can promote fruiting body development, while avoiding overwatering prevents osmotic stress that might inhibit sporulation.

Comparative Analysis: Nutrients vs. Stress

While both nutrient availability and stress trigger spore production, their mechanisms and outcomes differ. Nutrient-driven sporulation is a proactive response to resource limitation, often resulting in lightweight, easily dispersible spores. Stress-induced spores, however, are typically more robust, with thickened walls and enhanced resistance to environmental extremes. This distinction underscores the versatility of fungal reproductive strategies, tailored to specific ecological challenges. For example, *Penicillium* species produce conidia in response to nutrient depletion, whereas the same genus forms ascospores under oxidative stress, showcasing the adaptability of their reproductive toolkit.

Environmental triggers like nutrient availability and stress are not mere external pressures but essential cues that govern fungal life cycles. By fine-tuning spore production in response to these factors, fungi ensure their persistence across diverse and often hostile environments. Whether in a laboratory, a forest floor, or a bioreactor, understanding these triggers empowers us to harness fungal biology for innovation while appreciating the elegance of their survival strategies.

Are Fungal Spores Dangerous? Unveiling Health Risks and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Types of Fungal Spores: Classification of spores (e.g., zygospores, conidia) produced during meiosis

Fungi produce a diverse array of spores, each with unique structures and functions, often tied to their reproductive strategies. Among these, zygospores and conidia stand out as prime examples of spores produced during or in relation to meiosis, though their formation processes and roles differ significantly. Zygospores, for instance, are thick-walled, highly resilient structures formed through the fusion of haploid cells from two compatible mycelia, typically during sexual reproduction. This process involves meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity, and zygospores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh environmental conditions until favorable conditions trigger germination.

In contrast, conidia are asexual spores produced by mitosis, not meiosis, but their classification and role in fungal reproduction warrant attention. These spores are often produced at the tips or sides of specialized hyphae and serve as a rapid means of dispersal and colonization. While conidia do not involve meiosis, their production highlights the versatility of fungal reproductive strategies, complementing the genetic recombination achieved through meiosis in other spore types. Understanding this distinction is crucial for identifying fungal life cycles and their ecological roles.

Another critical spore type is the ascospore, produced within sac-like structures called asci during sexual reproduction. Meiosis occurs within the ascus, generating genetically diverse ascospores that are then released into the environment. These spores are typically thin-walled but can travel significant distances via wind or water, enabling fungi to colonize new habitats. For example, *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a model organism in genetics, produces ascospores that are essential for its survival and adaptation in varying environments.

Finally, basidiospores, produced by basidiomycetes, are another meiotic product, formed on club-shaped structures called basidia. These spores are often ejected forcibly, ensuring widespread dispersal. Mushrooms, a familiar basidiomycete, release billions of basidiospores, each capable of initiating a new mycelium. This strategy underscores the importance of meiosis in fungal reproduction, as it generates genetic diversity critical for adaptation and survival in dynamic ecosystems.

In practical terms, understanding these spore types aids in fungal identification, disease management, and biotechnological applications. For instance, zygospores’ durability makes them targets for studying fungal survival mechanisms, while ascospores and basidiospores are key in agricultural and forestry contexts, influencing crop health and ecosystem dynamics. By classifying and studying these spores, researchers can harness their unique properties for advancements in medicine, agriculture, and environmental science.

Can Spores Survive the Journey to Space? Exploring Microbial Resilience

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, fungi produce spores during meiosis, a process that involves the genetic recombination and reduction of chromosome number, resulting in haploid spores.

Fungi produce various types of spores during meiosis, including ascospores (in Ascomycetes), basidiospores (in Basidiomycetes), and zygospores (in Zygomycetes), depending on the fungal group.

Fungi produce spores during meiosis to ensure genetic diversity, facilitate dispersal, and survive harsh environmental conditions, as spores are often more resilient than vegetative cells.

Yes, meiosis in fungi is specifically linked to spore formation, as it is the reproductive phase where haploid spores are generated for dispersal and colonization.