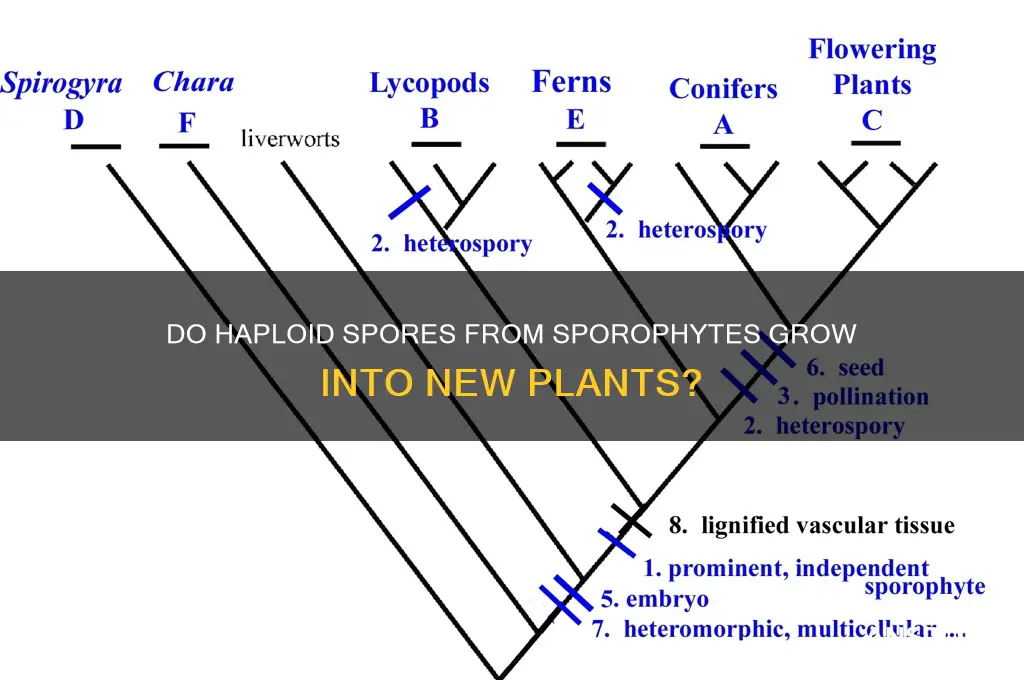

Haploid spores produced by sporophytes are a fundamental aspect of the life cycle of many plants, particularly in ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants. These spores are generated through the process of meiosis within the sporophyte generation, which is the diploid phase of the plant's life cycle. Once released, the haploid spores develop into gametophytes, the haploid phase, which are typically small, multicellular structures. Gametophytes then produce gametes—sperm and eggs—that, upon fertilization, give rise to a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in these organisms, highlighting the intricate relationship between sporophytes and the haploid spores they produce.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Spores | Haploid |

| Origin | Produced by sporophytes (diploid parent plant) |

| Process of Formation | Meiosis in spore-producing organs (e.g., sporangia) |

| Function | Develop into gametophytes (haploid generation) |

| Examples of Plants | Ferns, mosses, gymnosperms, angiosperms |

| Gametophyte Dependency | Gametophytes grow independently from spores |

| Role in Life Cycle | Part of alternation of generations (sporophyte → gametophyte → sporophyte) |

| Size | Microscopic, typically single-celled at dispersal |

| Dispersal Methods | Wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms |

| Environmental Adaptation | Often resistant to harsh conditions (e.g., desiccation) |

| Genetic Composition | Contain half the number of chromosomes of the sporophyte |

| Development Outcome | Produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporophyte Structure and Function

Sporophytes, the diploid phase in the life cycles of plants, algae, and some fungi, are structurally complex organisms designed to produce haploid spores. These spores, in turn, develop into gametophytes, ensuring the continuation of the species. The sporophyte’s structure is intricately adapted to its function, with specialized tissues and organs optimized for spore production and dispersal. For instance, in vascular plants like ferns and flowering plants, the sporophyte generation dominates the life cycle, manifesting as the familiar plant body we see, complete with roots, stems, and leaves.

Analyzing the sporophyte’s structure reveals a hierarchy of organization tailored to its reproductive role. In seed plants, such as conifers and angiosperms, sporophytes produce spores within cones or flowers, respectively. These reproductive structures house sporangia, the sites of spore formation. For example, pollen grains in angiosperms are male spores produced in anthers, while female spores (megaspores) develop within ovules. The sporophyte’s vascular system, composed of xylem and phloem, supports this process by transporting water, nutrients, and photosynthates to the developing spores and reproductive organs.

To understand the sporophyte’s function, consider its role in spore dispersal, a critical step in the life cycle. Sporophytes employ various mechanisms to ensure spores reach new habitats. Ferns, for instance, release spores from the undersides of their fronds, relying on wind for dispersal. In contrast, flowering plants often use animals or wind as vectors, with pollen grains adapted for adhesion or lightweight structures for wind travel. This diversity in dispersal strategies highlights the sporophyte’s evolutionary success in colonizing diverse environments.

Practical insights into sporophyte function can guide horticulture and conservation efforts. For example, gardeners cultivating ferns should mimic natural conditions by providing humid environments and avoiding direct sunlight to support sporophyte health and spore production. Similarly, in reforestation projects, understanding the sporophyte’s role in seed production can inform the timing and methods of seed collection and sowing. For instance, pine cones should be harvested when mature but before they open to release spores, ensuring maximum viability.

In conclusion, the sporophyte’s structure and function are a testament to nature’s ingenuity in ensuring species survival. From the vascular tissues that nourish developing spores to the reproductive organs that facilitate dispersal, every aspect of the sporophyte is finely tuned to its role. By studying these mechanisms, we gain not only a deeper appreciation of plant biology but also practical tools for horticulture, conservation, and agriculture. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or conservationist, understanding sporophytes unlocks new possibilities for working with and preserving plant life.

How Do Ferns Spread Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproduction Process

You may want to see also

Spore Formation Process

Spores are the microscopic units of life that enable plants, fungi, and some algae to reproduce and disperse. In the context of sporophytes, these structures play a pivotal role in the life cycle of many organisms, particularly in the alternation of generations seen in plants like ferns and mosses. The process of spore formation, or sporogenesis, is a complex yet fascinating mechanism that ensures the survival and propagation of species across diverse environments.

The Journey from Sporophyte to Spore

Sporophytes are the diploid phase in the life cycles of plants and certain algae, producing haploid spores through meiosis. This process begins within specialized structures called sporangia, which are often located on the sporophyte’s leaves, stems, or other reproductive organs. Inside the sporangia, sporogenous cells undergo meiosis, reducing the chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n). Each resulting spore is genetically unique, carrying half the genetic material of its parent sporophyte. This reduction in chromosome number is critical for the alternation of generations, allowing the subsequent gametophyte phase to develop from a single spore.

Steps in Spore Formation

Spore formation involves several distinct steps, each crucial for the successful production of viable spores. First, the sporophyte’s sporangia mature, signaling the initiation of sporogenesis. Next, sporogenous cells within the sporangia divide meiotically, producing four haploid spores per cell. These spores are then released through dehiscence, a process where the sporangium splits open, often triggered by environmental factors like dryness or wind. For example, in ferns, sporangia are clustered into structures called sori, which release spores when conditions are optimal for dispersal. Once released, spores are carried by wind, water, or animals to new locations, where they germinate under suitable conditions to form gametophytes.

Environmental Factors and Spore Viability

The success of spore formation and dispersal is heavily influenced by environmental conditions. Humidity, temperature, and light play critical roles in both sporogenesis and spore germination. For instance, excessive moisture can hinder spore release by preventing sporangia from drying and opening, while extreme temperatures may damage spore viability. Practical tips for cultivating spore-producing plants include maintaining moderate humidity levels (around 50-70%) and ensuring adequate air circulation to facilitate spore dispersal. For hobbyists growing ferns or mosses, placing sporangia-bearing plants in well-ventilated areas and avoiding overwatering can enhance spore production and germination rates.

Comparative Analysis: Spores Across Kingdoms

While the spore formation process shares similarities across plants, fungi, and algae, there are notable differences. In fungi, spores are produced asexually through structures like conidia or sexually via asci and basidia, depending on the species. Algae, such as the green alga *Chlamydomonas*, produce spores through similar meiotic processes but often in response to environmental stressors like nutrient depletion. In contrast, plant spores are typically produced in a more structured, cyclical manner tied to the alternation of generations. Understanding these variations highlights the adaptability of spore formation as a reproductive strategy across diverse organisms.

Takeaway: The Significance of Spore Formation

Spore formation is a fundamental process that ensures genetic diversity and species survival in changing environments. By producing haploid spores, sporophytes enable the next generation to adapt to new conditions, whether through genetic recombination or rapid dispersal. For gardeners, botanists, and enthusiasts, understanding this process can enhance the cultivation and conservation of spore-producing plants. By mimicking natural conditions and respecting the delicate balance of sporogenesis, we can foster thriving ecosystems and appreciate the intricate beauty of life’s reproductive strategies.

Streptococcus and Spore Formation: Unraveling the Bacterial Mystery

You may want to see also

Haploid Spore Development

Haploid spores, produced by sporophytes in plants and certain algae, are the cornerstone of alternation of generations—a life cycle where organisms alternate between diploid and haploid phases. These spores, carrying a single set of chromosomes, develop into gametophytes, which in turn produce gametes for sexual reproduction. This process is not merely a biological curiosity but a fundamental mechanism ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability in species ranging from ferns to mosses.

Consider the fern as a prime example. The sporophyte, the familiar leafy plant, releases haploid spores via structures called sporangia. Each spore, when deposited in a suitable environment, germinates into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte (prothallus). This gametophyte, though diminutive, is a self-sustaining organism that produces both sperm and eggs. The key to successful spore development lies in environmental conditions: adequate moisture, light, and temperature are critical for germination and growth. For instance, ferns thrive in humid, shaded areas, where spores can absorb water and initiate metabolic activity without desiccation.

Analyzing the developmental pathway reveals a delicate balance between genetic programming and environmental cues. Spores are equipped with stored nutrients and protective coatings, enabling them to survive harsh conditions until optimal growth opportunities arise. Once activated, the spore undergoes cell division, forming a multicellular gametophyte. This stage is particularly vulnerable; for example, in mosses, the gametophyte must remain moist for sperm to swim to the egg, a process that can be disrupted by dry conditions. Thus, spore development is not just about growth but also about timing and resilience.

Practical applications of understanding haploid spore development extend to horticulture and conservation. Gardeners cultivating ferns or mosses must replicate natural conditions, such as misting soil to maintain humidity and providing indirect light to prevent gametophyte desiccation. In conservation efforts, reintroducing spore-producing plants to degraded habitats requires knowledge of spore dispersal mechanisms and germination requirements. For instance, spores of certain algae are used in aquaculture to control algal blooms, highlighting their ecological and economic significance.

In conclusion, haploid spore development is a marvel of biological efficiency, blending genetic simplicity with environmental responsiveness. From the forest floor to the laboratory, mastering this process unlocks potential in agriculture, ecology, and biotechnology. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or conservationist, appreciating the intricacies of spore development transforms how we interact with and preserve the natural world.

Are Spore Syringes Illegal? Understanding Legal Boundaries and Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.99

Environmental Factors Affecting Growth

Spores, the haploid reproductive units produced by sporophytes, are remarkably resilient yet highly sensitive to environmental cues during their growth phase. Temperature plays a pivotal role in spore germination and development. For instance, ferns require a narrow temperature range—typically between 20°C and 28°C—for optimal spore growth. Deviations outside this range can inhibit germination or lead to malformed gametophytes. In contrast, moss spores exhibit greater temperature tolerance, often germinating in cooler environments as low as 10°C, making them more adaptable to diverse climates. Understanding these thermal thresholds is crucial for cultivating spore-producing plants in controlled environments or predicting their distribution in the wild.

Light exposure is another critical factor influencing spore growth, particularly in the early stages of development. Many spore-producing species, such as liverworts, require specific light wavelengths to trigger germination. Blue light (450–495 nm) has been shown to stimulate spore germination in *Marchantia polymorpha*, while red light (620–750 nm) can inhibit it. This sensitivity to light spectra highlights the importance of photoreceptors in spore development and underscores the need for precise light management in horticultural settings. For home growers, using LED grow lights with adjustable spectra can mimic natural conditions and enhance spore viability.

Moisture availability is equally vital, as spores are highly dependent on water for activation and initial growth. In arid environments, spores may remain dormant for years, waiting for sufficient moisture to initiate germination. For example, desert mosses like *Syntrichia caninervis* have evolved to germinate rapidly after rare rainfall events, ensuring survival in harsh conditions. However, excessive moisture can lead to fungal infections or spore desiccation, particularly in humid tropical regions. Maintaining a humidity level of 60–80% is ideal for most spore cultures, with regular misting to prevent drying without promoting mold growth.

Nutrient availability in the substrate also significantly impacts spore growth. While spores are initially self-sufficient, relying on stored nutrients, they quickly deplete these reserves and require external sources for sustained development. A balanced substrate enriched with nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK ratio of 10-10-10) supports robust gametophyte formation. Organic matter, such as peat moss or compost, can enhance nutrient retention and water-holding capacity. For field applications, soil testing and amendments are essential to ensure optimal nutrient levels, particularly in degraded or nutrient-poor environments.

Finally, atmospheric gases, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂), influence spore growth dynamics. Elevated CO₂ levels (up to 1,000 ppm) have been shown to accelerate gametophyte development in species like *Physcomitrella patens*, a model moss. However, excessive CO₂ can lead to abnormal growth patterns or reduced photosynthetic efficiency. In controlled environments, monitoring and adjusting CO₂ concentrations using sensors and ventilation systems can optimize growth conditions. For outdoor cultivation, planting spore-producing species in areas with natural CO₂ enrichment, such as near decomposing organic matter, can enhance their growth potential.

By manipulating these environmental factors—temperature, light, moisture, nutrients, and gases—growers and researchers can maximize the success of haploid spores derived from sporophytes. Each factor interacts dynamically, requiring careful calibration to create an optimal growth environment. Whether in a laboratory, greenhouse, or natural setting, understanding these influences empowers individuals to cultivate spore-producing plants effectively and sustainably.

Can Poison Ivy Spores Spread to People? Understanding the Risks

You may want to see also

Life Cycle Transition to Gametophytes

In the intricate dance of plant reproduction, the transition from sporophyte to gametophyte marks a pivotal shift in the life cycle. Haploid spores, produced by the sporophyte, are the vehicles for this transformation. These spores, upon dispersal, germinate under favorable conditions to give rise to gametophytes—the haploid phase responsible for producing gametes. This process is not merely a biological necessity but a testament to the adaptability and resilience of plant life. For instance, in ferns, a single sporophyte can release thousands of spores, each with the potential to develop into a new gametophyte, ensuring species survival across diverse environments.

Consider the steps involved in this transition, a process both delicate and precise. First, spores must land in an environment with adequate moisture, light, and nutrients. Without these, germination is halted, underscoring the importance of habitat suitability. Once germinated, the spore develops into a protonema (in mosses) or a heart-shaped prothallus (in ferns), structures that are often microscopic yet crucial. These gametophytes then produce gametes—sperm and eggs—through specialized organs. The timing of this development is critical; for example, in mosses, the male gametophyte must release sperm when the female archegonia are receptive, a process often synchronized by environmental cues like rainfall.

The transition to gametophytes is not without challenges. Spores are highly susceptible to desiccation and predation, making their journey from sporophyte to germination a perilous one. To mitigate this, some plants, like certain liverworts, produce spores with protective coatings or elaters—spring-like structures that aid in dispersal. Additionally, the gametophyte phase is typically short-lived, relying on the sporophyte for long-term survival. This interdependence highlights the evolutionary balance between the two phases, where the sporophyte provides stability and the gametophyte ensures genetic diversity through sexual reproduction.

Practical observations of this transition can deepen our appreciation for plant biology. For hobbyists cultivating ferns or mosses, understanding this cycle is key to successful propagation. For instance, maintaining high humidity and indirect light can mimic the spore’s natural habitat, encouraging germination. Similarly, in educational settings, observing the development of a fern prothallus under a microscope can illustrate the complexity of this phase. Such hands-on engagement not only demystifies the process but also fosters a deeper connection to the natural world.

In conclusion, the life cycle transition to gametophytes is a marvel of biological efficiency and adaptability. From the production of haploid spores to their development into gamete-producing structures, each step is finely tuned to ensure the continuation of the species. By studying this process, we gain insights into the resilience of plant life and the intricate mechanisms that drive biodiversity. Whether in a laboratory, classroom, or garden, witnessing this transition offers a profound reminder of the interconnectedness of all living things.

Pressure Cooking Spore Syringes: Safe Method or Risky Experiment?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, haploid spores are produced directly by sporophytes through the process of meiosis in plants and algae.

Haploid spores grow into gametophytes, which are the haploid phase of the plant life cycle responsible for producing gametes.

Sporophytes produce haploid spores through meiosis, reducing the chromosome number by half.

No, haploid spores develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes that fuse to form a diploid zygote, eventually growing into a new sporophyte.

Sporophytes produce haploid spores during the sporophyte phase, which is the diploid stage of the plant life cycle.