Gram-negative rods are a diverse group of bacteria characterized by their outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides, which distinguishes them from gram-positive bacteria. While some bacteria, such as certain gram-positive species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are known for their ability to form spores as a survival mechanism, gram-negative rods generally do not form spores. Instead, they rely on other strategies, such as biofilm formation or resistance mechanisms, to endure harsh environmental conditions. Notable exceptions include *Bacillus* species, which are gram-positive, and *Clostridium*, but among gram-negative rods, spore formation is not a typical feature. This distinction is crucial for understanding their survival, pathogenicity, and treatment in clinical and environmental contexts.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Gram-Negative Rods Form Spores? | No, most Gram-negative rods do not form spores. |

| Exceptions | A few rare exceptions exist, such as Adenosynbacter and Oceanibacillus, but these are not typical Gram-negative rods. |

| Spore Formation Mechanism | Sporulation is primarily a feature of Gram-positive bacteria, especially in the genus Bacillus and Clostridium. |

| Cell Wall Structure | Gram-negative rods have a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane, which does not support spore formation. |

| Survival Strategies | Gram-negative rods rely on other mechanisms for survival, such as biofilm formation, antibiotic resistance, and metabolic versatility. |

| Examples of Non-Spore Forming Gram-Negative Rods | Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Enterobacter. |

| Significance | The inability to form spores makes Gram-negative rods more susceptible to environmental stresses compared to spore-forming bacteria. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Sporulation in Gram-Negative Bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are primarily known for their outer membrane and thin peptidoglycan layer, which distinguish them from Gram-positive counterparts. While sporulation is a hallmark of certain Gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, it is far less common in Gram-negative species. However, exceptions exist, and understanding these rare cases is crucial for both clinical and environmental microbiology. For instance, *Chromobacterium violaceum*, a Gram-negative rod, produces spore-like structures under specific stress conditions, challenging the traditional dichotomy of sporulation in bacterial groups.

Analyzing the mechanisms of sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria reveals a distinct process compared to Gram-positive organisms. Unlike the well-studied endospore formation in *Bacillus subtilis*, Gram-negative sporulation involves the production of exospores, which are encased in an outer membrane rather than a thick peptidoglycan coat. This structural difference impacts spore resilience, as exospores are generally less resistant to environmental stressors like heat and desiccation. Research on *Chromobacterium* spp. shows that sporulation is triggered by nutrient deprivation and regulated by unique genetic pathways, distinct from those in Gram-positive bacteria.

From a practical standpoint, identifying sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria has significant implications for infection control and treatment. Exospores can survive in harsh environments, potentially leading to persistent infections or contamination in healthcare settings. For example, *C. violaceum* exospores have been isolated from water sources, posing a risk of transmission. Clinicians should be aware that standard sterilization methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, may not effectively eliminate exospores, necessitating alternative disinfection strategies like prolonged exposure to higher temperatures or chemical agents.

Comparatively, the rarity of sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria underscores the evolutionary divergence in survival strategies between bacterial groups. While Gram-positive spores are highly resilient, Gram-negative exospores represent a more specialized adaptation, often limited to specific genera. This distinction highlights the importance of species-specific research in microbiology. For instance, studying *C. violaceum* sporulation can provide insights into its role in environmental persistence and pathogenesis, aiding in the development of targeted interventions.

In conclusion, sporulation in Gram-negative bacteria, though uncommon, is a fascinating and clinically relevant phenomenon. Understanding the unique mechanisms and implications of exospore formation in species like *Chromobacterium violaceum* can enhance diagnostic accuracy, infection control, and treatment strategies. By focusing on these exceptions, microbiologists can bridge gaps in knowledge and improve outcomes in both healthcare and environmental settings.

Where to Buy Magic Mushroom Spores: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Common Gram-Negative Rod Species

Gram-negative rods are a diverse group of bacteria characterized by their thin peptidoglycan cell wall and outer membrane containing lipopolysaccharides. While spore formation is a survival mechanism commonly associated with Gram-positive bacteria like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus*, it is rare among Gram-negative rods. However, exceptions exist, and understanding these species is crucial for clinical and environmental contexts. Among the vast array of Gram-negative rods, only a few are known to form spore-like structures or exhibit similar survival strategies.

One notable example is *Xenorhabdus nematophila*, a Gram-negative rod that forms resistant cyst-like structures under stress. While not true spores, these structures allow the bacterium to survive harsh conditions, such as desiccation or nutrient deprivation. This species is symbiotically associated with entomopathogenic nematodes and plays a role in insect pathogenesis. Its ability to form cysts highlights an adaptive strategy that blurs the line between traditional spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria.

Another species of interest is *Stenotrophomonas maltophilia*, a ubiquitous Gram-negative rod found in aquatic and soil environments. While it does not form spores, it exhibits remarkable environmental resilience, surviving in diverse habitats, including medical devices and hospital settings. Its resistance to multiple antibiotics and ability to form biofilms make it a significant opportunistic pathogen, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Understanding its survival mechanisms is essential for infection control and treatment strategies.

In contrast, *Escherichia coli*, one of the most well-known Gram-negative rods, does not form spores. However, it employs other survival tactics, such as biofilm formation and persistence in the gastrointestinal tract. Certain strains, like enterohemorrhagic *E. coli* (EHEC), can cause severe infections, emphasizing the importance of hygiene and proper food handling. For instance, cooking ground beef to an internal temperature of 160°F (71°C) effectively kills *E. coli* and prevents foodborne illness.

Finally, *Pseudomonas aeruginosa* exemplifies a Gram-negative rod with exceptional environmental adaptability. While it does not form spores, it thrives in diverse niches, from soil and water to hospital environments. Its ability to survive in low-nutrient conditions and resist multiple antibiotics makes it a leading cause of nosocomial infections. Practical tips for preventing *P. aeruginosa* infections include regular hand hygiene, proper disinfection of medical equipment, and vigilant monitoring of high-risk patients, such as those with cystic fibrosis or burns.

In summary, while spore formation is rare among Gram-negative rods, species like *Xenorhabdus nematophila* demonstrate alternative survival strategies. Others, such as *Stenotrophomonas maltophilia*, *Escherichia coli*, and *Pseudomonas aeruginosa*, rely on biofilm formation, environmental resilience, and antibiotic resistance to persist. Recognizing these mechanisms is vital for managing infections and implementing effective control measures in clinical and environmental settings.

Breathing in Spores: Unraveling Dizziness, Nausea, and Breathing Difficulties

You may want to see also

Conditions for Spore Formation

Spore formation, or sporulation, is a survival mechanism primarily associated with certain Gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. However, the question of whether Gram-negative rods form spores is less straightforward. While the majority of Gram-negative bacteria do not produce spores, there are exceptions, such as *Adenosylcobalamin* (a rare case) and some species in the genus *Cyanobacteria*. For these organisms, spore formation is contingent on specific environmental conditions that trigger this adaptive response. Understanding these conditions is crucial for both microbiological research and practical applications, such as controlling bacterial survival in extreme environments.

The first critical condition for spore formation is nutrient deprivation, particularly the depletion of carbon and nitrogen sources. When Gram-negative bacteria capable of sporulation sense starvation, they initiate a complex genetic program to redirect cellular resources toward spore development. For instance, in *Cyanobacteria*, nitrogen limitation triggers the differentiation of vegetative cells into spores, ensuring long-term survival. This process is highly regulated and requires precise environmental cues, such as a specific pH range (typically neutral to slightly alkaline) and optimal temperature (around 30–37°C). Deviations from these parameters can inhibit sporulation, emphasizing the need for tightly controlled conditions.

Another key factor is the presence of specific signaling molecules and environmental stressors. For example, some Gram-negative bacteria respond to oxidative stress or desiccation by initiating spore formation. In laboratory settings, researchers often simulate these conditions by gradually reducing nutrient availability and introducing mild stressors, such as hydrogen peroxide at low concentrations (e.g., 0.1–0.5 mM). Additionally, the role of quorum sensing—a cell-to-cell communication mechanism—cannot be overlooked. Certain bacteria require a minimum population density, detected through quorum-sensing molecules, to activate sporulation genes. This ensures that spore formation occurs only when it is most beneficial for the bacterial community.

Practical tips for inducing spore formation in Gram-negative bacteria include using defined minimal media to precisely control nutrient levels and monitoring environmental parameters with tools like pH meters and incubators. For researchers, maintaining a sterile environment is essential to avoid contamination, as non-spore-forming bacteria can outcompete sporulating species. It’s also important to note that not all Gram-negative rods will respond to these conditions, so species-specific protocols are necessary. For example, *Cyanobacteria* may require additional light exposure to mimic their natural habitat, while other species might need specific trace elements to support sporulation.

In conclusion, while spore formation in Gram-negative rods is less common, it is not impossible. The conditions for sporulation are stringent, requiring nutrient deprivation, specific environmental stressors, and precise regulation of factors like pH, temperature, and population density. By understanding and manipulating these conditions, researchers can study this rare phenomenon and potentially harness it for biotechnological applications, such as biofilm control or environmental remediation. This knowledge also highlights the remarkable adaptability of bacteria, even within the constraints of their Gram classification.

Cheating Food in Spore: Tips, Tricks, and Ethical Considerations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.25

Differences from Gram-Positive Spores

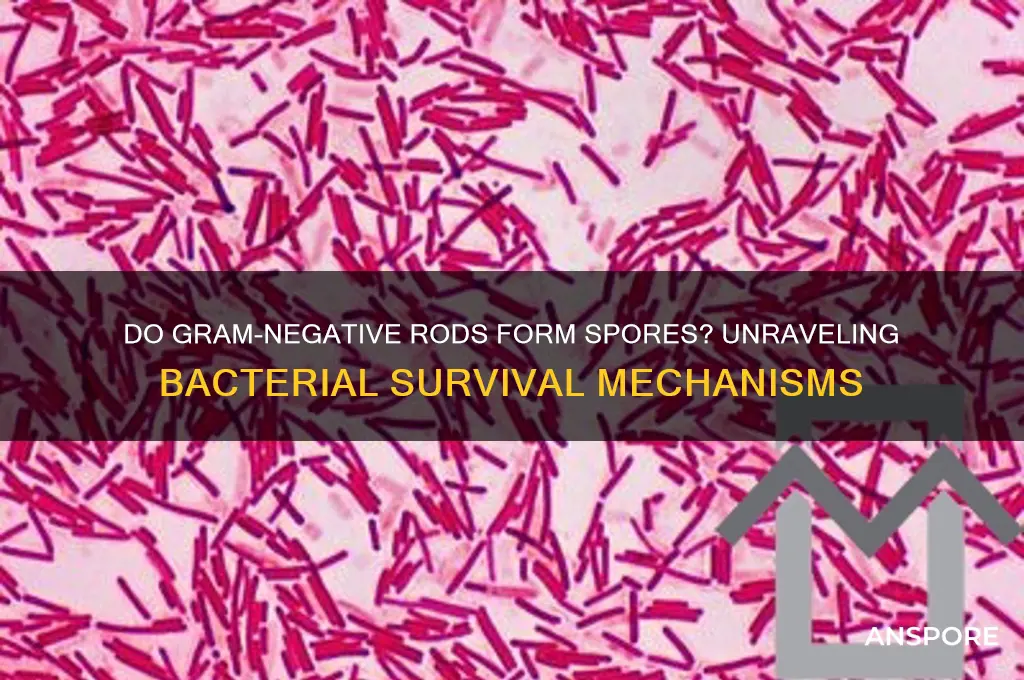

Gram-negative rods and Gram-positive bacteria differ fundamentally in their ability to form spores, a critical survival mechanism in harsh environments. While Gram-positive bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* are well-known spore-formers, Gram-negative rods generally do not produce spores. This distinction is rooted in their cell wall structure and metabolic pathways. Gram-negative bacteria, with their complex double-membrane cell walls, lack the genetic machinery required for sporulation, a process tightly regulated in Gram-positive species. Understanding this difference is essential for microbiologists, clinicians, and researchers studying bacterial survival strategies.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in Gram-negative rods simplifies their control in clinical and industrial settings. Unlike Gram-positive spores, which can withstand extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and chemicals, Gram-negative rods are more susceptible to standard sterilization methods. For instance, autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes effectively kills most Gram-negative bacteria, whereas Gram-positive spores may require longer exposure times or higher temperatures. This makes Gram-negative rods less problematic in contamination scenarios, though their ability to develop antibiotic resistance remains a significant concern.

However, exceptions to the rule exist, and understanding them is crucial. Some Gram-negative bacteria, like *Chromobacterium violaceum*, produce spore-like structures under specific conditions, though these are not true endospores. These structures lack the durability of Gram-positive spores and are not considered a primary survival mechanism. Researchers must differentiate between true sporulation and such anomalous formations to avoid misinterpretation in laboratory studies. This highlights the importance of precise terminology and rigorous experimental design in microbiology.

Clinically, the inability of Gram-negative rods to form spores influences treatment strategies. While Gram-positive spore-formers like *Clostridioides difficile* require targeted therapies to eradicate persistent spores, Gram-negative infections are typically managed with antibiotics that penetrate their outer membrane. However, the rise of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens, such as *Pseudomonas aeruginosa* and *Klebsiella pneumoniae*, necessitates innovative approaches like combination therapy or phage treatment. Unlike spores, which can reactivate after treatment, Gram-negative rods are less likely to recur post-eradication, provided the infection is fully treated.

In summary, the absence of spore formation in Gram-negative rods distinguishes them from Gram-positive bacteria, influencing their survival, control, and clinical management. While exceptions exist, this characteristic simplifies their handling in most contexts. Researchers and clinicians must remain vigilant about emerging anomalies and resistant strains, ensuring accurate identification and effective treatment strategies. This knowledge bridges the gap between fundamental microbiology and practical applications, fostering advancements in infection control and therapeutic development.

Are Fungal Spores on Rose Leaves Harmful? A Gardener's Guide

You may want to see also

Clinical Significance of Spores

Gram-negative rods are a diverse group of bacteria, but unlike their Gram-positive counterparts, they generally do not form spores. This distinction is crucial in clinical settings, as spores significantly impact disease persistence, treatment challenges, and infection control. While Gram-negative rods lack this survival mechanism, understanding the clinical significance of spores in other bacteria provides valuable context for managing infections and preventing outbreaks.

Spores, highly resistant dormant forms produced by certain bacteria like *Clostridioides difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis*, pose unique challenges in healthcare. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions—heat, radiation, and disinfectants—allows them to persist in hospital environments for months. This resilience increases the risk of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), particularly in immunocompromised patients. For instance, *C. difficile* spores can survive on surfaces and hands, leading to transmission despite standard cleaning protocols.

Effective infection control hinges on spore-specific strategies. Traditional alcohol-based hand sanitizers are ineffective against spores; instead, handwashing with soap and water is essential. Environmental cleaning requires spore-killing agents like chlorine-based disinfectants, with contact times of at least 10 minutes for optimal efficacy. In clinical practice, isolating patients with spore-forming infections and employing barrier precautions are critical to prevent spread.

From a treatment perspective, spores complicate antibiotic therapy. Their dormant state renders them impervious to many antibiotics, necessitating agents like vancomycin or fidaxomicin for *C. difficile* infections. Even after spore germination, the vegetative form may require prolonged treatment to prevent recurrence. For example, *C. difficile* treatment often involves 10–14 days of oral vancomycin (125 mg qid) or fidaxomicin (200 mg bid), with extended or tapered regimens for high-risk patients.

Comparatively, the absence of spore formation in Gram-negative rods simplifies their management but highlights the need for vigilance against spore-forming pathogens. While Gram-negative infections like *E. coli* or *Pseudomonas aeruginosa* are treated with beta-lactams or carbapenems, spore-forming bacteria demand a tailored approach. Recognizing this difference ensures appropriate treatment and infection control measures, reducing morbidity and mortality in clinical settings.

In summary, while Gram-negative rods do not form spores, the clinical significance of spores in other bacteria underscores the need for targeted strategies in healthcare. From stringent disinfection protocols to specific antibiotic regimens, addressing spore-related challenges is essential for patient safety and outbreak prevention. This knowledge bridges the gap between microbiology and clinical practice, guiding effective management of spore-associated infections.

Can C. Diff Spores Be Inhaled? Understanding Airborne Transmission Risks

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, gram-negative rods generally do not form spores. Sporulation is more commonly observed in gram-positive bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species.

Yes, there are rare exceptions. For example, *Adenosylcobalamin 8-phosphatase* (formerly known as *Sinorhizobium meliloti*) and some species in the genus *Azotobacter* are gram-negative bacteria capable of forming cyst-like spores under specific conditions.

Most gram-negative rods lack the genetic and structural mechanisms required for sporulation. Their cell wall composition and metabolic pathways differ from those of gram-positive spore-formers, making spore formation energetically unfavorable or impossible.

![Substances screened for ability to reduce thermal resistance of bacterial spores 1959 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Z99EgARVL._AC_UL320_.jpg)