Ferns are unique plants that reproduce through spores rather than seeds, and understanding how they spread these spores is key to appreciating their life cycle. Unlike flowering plants, ferns produce tiny, dust-like spores on the undersides of their fronds, typically in structures called sori. When mature, these spores are released and dispersed by wind, water, or even animals, allowing ferns to colonize new areas. This method of reproduction enables ferns to thrive in diverse environments, from shady forests to rocky crevices, making them one of the most widespread and resilient plant groups on Earth.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method of Spores Spread | Ferns spread spores through a process called sporulation. Spores are released from the undersides of fern leaves (fronds) and dispersed by wind, water, or animals. |

| Sporangia Location | Spores are produced in structures called sporangia, which are typically found on the undersides of mature fern fronds, often clustered in groups called sori. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are lightweight and can travel long distances via wind (primary method). Some spores may also be carried by water or adhere to animals for dispersal. |

| Spores Size | Fern spores are microscopic, typically ranging from 20 to 60 micrometers in diameter, allowing for efficient wind dispersal. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are part of the alternation of generations in ferns. They develop into prothalli (gametophytes), which then produce gametes to form new fern plants (sporophytes). |

| Environmental Factors | Spores are more likely to spread and germinate in humid, shaded environments, which are typical of fern habitats. |

| Seasonality | Ferns often release spores during specific seasons, usually in spring or summer, depending on the species and climate. |

| Adaptations for Spread | Some ferns have elastic structures in their sporangia that help eject spores, enhancing dispersal efficiency. |

| Role in Ecosystem | Fern spores contribute to plant diversity and serve as a food source for certain microorganisms and small invertebrates. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Production Mechanisms: Ferns develop sporangia on the undersides of leaves to produce and release spores

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading fern spores over long distances efficiently

- Environmental Factors: Humidity, light, and temperature influence spore release and germination success in ferns

- Life Cycle Stages: Spores grow into gametophytes, which then develop into new fern plants

- Adaptation Strategies: Ferns evolved lightweight spores and protective coatings to enhance survival and dispersal

Spore Production Mechanisms: Ferns develop sporangia on the undersides of leaves to produce and release spores

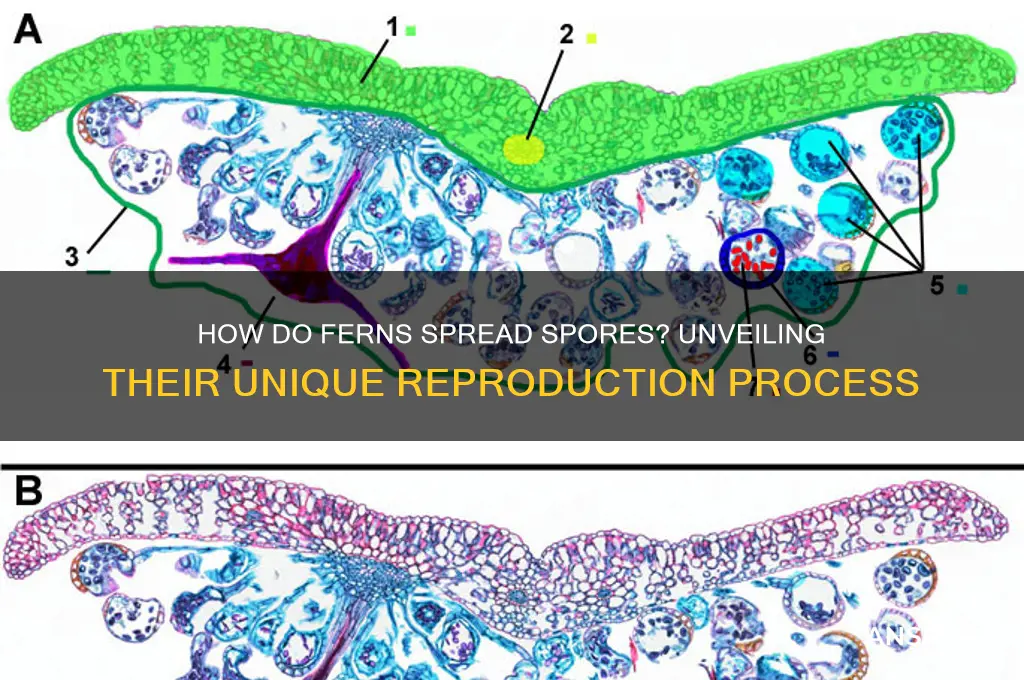

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and their spore production mechanisms are both intricate and efficient. At the heart of this process are the sporangia, tiny structures that develop on the undersides of fern leaves, also known as fronds. These sporangia serve as factories for spore production, each one capable of releasing hundreds of spores into the environment. The placement of sporangia on the leaf’s underside is strategic, protecting them from excessive moisture loss while ensuring optimal dispersal when conditions are right.

The development of sporangia follows a precise sequence. As the fern matures, clusters of sporangia, known as sori, form in distinct patterns unique to each species. For example, maidenhair ferns have circular sori, while Bracken ferns display linear arrangements. Inside each sporangium, spores are produced through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number, ensuring genetic diversity. This diversity is crucial for ferns to adapt to varying environments, from shaded forest floors to rocky crevices.

Once mature, the sporangia undergo a remarkable mechanism to release spores. As they dry out, the cells in the sporangium’s wall change shape, creating tension. This tension builds until the sporangium suddenly snaps open, launching spores into the air. This process, known as ballistospory, can propel spores several centimeters, increasing their chances of reaching suitable habitats. For gardeners cultivating ferns, understanding this mechanism can inform watering practices—allowing the soil to dry slightly between waterings mimics natural conditions and encourages healthy spore production.

Comparatively, ferns’ spore dispersal methods differ significantly from those of seed-producing plants. While seeds are often encased in protective structures and dispersed by animals or wind, fern spores are lightweight and rely solely on wind currents. This makes their dispersal highly dependent on environmental factors, such as air movement and humidity. For enthusiasts looking to propagate ferns from spores, creating a humid, well-ventilated environment—like a sealed container with moist soil—can simulate ideal conditions for spore germination.

In practical terms, observing spore production in ferns can be a rewarding experience. During late summer or early fall, examine the undersides of mature fronds for sori. A magnifying glass can reveal the intricate patterns and structures of the sporangia. For educational purposes, collecting spores for germination experiments is straightforward: place a mature frond with visible sori on a sheet of paper, and within days, the spores will drop, ready for sowing. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding of fern biology but also highlights the elegance of their reproductive strategies.

How to Play Spore on LAN: A Step-by-Step Multiplayer Guide

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals aid in spreading fern spores over long distances efficiently

Ferns, ancient plants that have thrived for millions of years, rely on efficient dispersal methods to spread their spores across vast distances. Among these methods, wind, water, and animals play pivotal roles, each contributing uniquely to the fern's reproductive success. Wind, the most common agent, carries lightweight spores aloft, allowing them to travel kilometers before settling in new habitats. This passive yet effective strategy ensures ferns colonize diverse environments, from forest floors to rocky outcrops.

Water, though less universal, is equally vital in specific ecosystems. Fern spores, often hydrophobic, can float on water surfaces, enabling dispersal in wetlands, streams, and rain-soaked terrains. For instance, species like the royal fern (*Osmunda regalis*) thrive in moist environments where water aids spore movement. This method, while localized, ensures ferns establish themselves in nutrient-rich areas, fostering robust growth.

Animals, often overlooked, contribute through indirect yet impactful means. Small creatures like insects or birds may carry spores on their bodies, inadvertently transporting them to new locations. Additionally, larger animals trampling through fern-rich areas can dislodge spores, aiding in their spread. This symbiotic relationship highlights how ferns leverage external agents to enhance their reproductive reach.

Practical observations reveal that wind-dispersed spores are most effective in open, elevated areas, while water dispersal thrives in low-lying, humid regions. Gardeners cultivating ferns can mimic these conditions by placing spore-bearing plants in breezy spots or near water features. For enthusiasts, understanding these methods not only deepens appreciation for ferns but also aids in successful propagation and conservation efforts.

In essence, the interplay of wind, water, and animals forms a dynamic network that ensures ferns’ survival and proliferation. Each method, tailored to specific environments, underscores the adaptability of these resilient plants. By studying these dispersal strategies, we gain insights into ferns’ ecological roles and learn how to support their growth in both natural and cultivated settings.

Can Spores Be Deadly? Uncovering the Truth About Their Lethal Potential

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: Humidity, light, and temperature influence spore release and germination success in ferns

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on spores for reproduction, and the success of this process is intricately tied to environmental conditions. Humidity, for instance, plays a pivotal role in spore release. Ferns typically thrive in moist environments, and a relative humidity of 70-90% is ideal for the maturation and dispersal of spores. In drier conditions, the sporangia—the structures housing the spores—may fail to open, trapping spores and hindering reproduction. For gardeners cultivating ferns, maintaining consistent moisture levels through misting or humidifiers can significantly enhance spore release, especially in indoor settings.

Light, though often overlooked, is another critical factor influencing fern spore germination. While ferns generally prefer shaded environments, the intensity and duration of light exposure can affect the viability of spores. Studies show that spores exposed to low to moderate light (around 50-200 μmol/m²/s) germinate more successfully than those in complete darkness or intense light. This is because light triggers physiological processes necessary for spore activation. For optimal results, place fern spores in a location with filtered, indirect light, mimicking their natural understory habitat.

Temperature acts as a double-edged sword in fern spore reproduction, affecting both release and germination. Most fern species release spores within a temperature range of 15-25°C (59-77°F), with extremes inhibiting the process. Germination, however, often requires a slightly warmer range, typically 20-30°C (68-86°F), depending on the species. For example, tropical ferns like *Nephrolepis exaltata* (Boston fern) may require higher temperatures for successful germination compared to temperate species like *Dryopteris filix-mas* (male fern). Gardeners should monitor temperature fluctuations, especially during the critical stages of spore development and germination, to ensure reproductive success.

The interplay of these environmental factors underscores the delicate balance ferns require for survival. For instance, high humidity without adequate light can lead to mold growth, which competes with spores for resources. Similarly, optimal temperature without sufficient moisture can render spores dormant. A practical approach is to create a controlled environment, such as a terrarium, where humidity, light, and temperature can be regulated. Using a hygrometer to monitor humidity, a grow light to provide consistent illumination, and a heating mat to stabilize temperature can dramatically improve spore germination rates.

In conclusion, understanding how humidity, light, and temperature influence fern spore release and germination is essential for both conservation and cultivation efforts. By replicating the ferns' natural habitat conditions, enthusiasts can foster successful reproduction, ensuring the longevity of these ancient plants. Whether in a garden or laboratory setting, precision in managing these environmental factors is key to unlocking the reproductive potential of ferns.

Are Bacterial Spore Cells Dead During Staining? Unraveling the Mystery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$89.99 $114.99

Life Cycle Stages: Spores grow into gametophytes, which then develop into new fern plants

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, rely on a unique reproductive strategy centered around spores. These microscopic, dust-like particles are the starting point of their life cycle. Dispersed by wind, water, or even animals, spores embark on a journey to find suitable environments for germination. This initial stage is crucial, as it determines the success of the entire life cycle. Without successful spore dispersal, ferns cannot propagate and colonize new areas.

Once a spore lands in a favorable environment—typically moist and shaded—it germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure often overlooked due to its size. This gametophyte is a self-sustaining organism, capable of photosynthesis, but its primary role is reproductive. It produces both male (sperm) and female (egg) cells, which, under the right conditions, unite to form a zygote. This process, known as fertilization, marks the transition from the gametophyte stage to the next phase of the fern's life cycle.

The zygote develops into a young fern plant, or sporophyte, which grows directly from the gametophyte. This new plant is the familiar fern we recognize, with its fronds and fiddleheads. As the sporophyte matures, it produces spore cases (sporangia) on the undersides of its leaves. These sporangia release spores, completing the cycle and ensuring the next generation of ferns. This alternation between gametophyte and sporophyte generations is a defining feature of fern reproduction.

Understanding this life cycle is essential for gardeners and conservationists alike. For instance, to cultivate ferns successfully, one must replicate their preferred habitat: moist soil, indirect light, and humidity. Spores should be sown on a sterile medium, such as a mix of peat and sand, and kept consistently damp. Patience is key, as gametophytes can take weeks to develop, and sporophytes may take months to mature. By mimicking natural conditions, enthusiasts can witness the entire life cycle unfold, from spore to thriving fern.

In comparison to seed-producing plants, ferns’ reliance on spores and water for fertilization highlights their ancient evolutionary origins. This method, while less efficient in dry environments, has sustained ferns for over 360 million years. Their resilience and adaptability make them a fascinating subject for study and a valuable addition to ecosystems. By appreciating the intricacies of their life cycle, we gain insight into the diversity of plant reproduction strategies and the delicate balance of nature.

Exploring the Genetic Diversity of Spores: Unveiling Nature's Hidden Complexity

You may want to see also

Adaptation Strategies: Ferns evolved lightweight spores and protective coatings to enhance survival and dispersal

Ferns, ancient plants that have thrived for millions of years, rely on spores for reproduction, a strategy that hinges on their ability to disperse widely and survive harsh conditions. To achieve this, ferns have evolved two key adaptations: lightweight spores and protective coatings. These features are not merely coincidental but are finely tuned mechanisms that ensure the species’ continuity in diverse environments. Lightweight spores, often measuring just a few micrometers in diameter, minimize energy expenditure during dispersal, allowing them to travel farther on air currents or water. This reduction in size, however, comes with vulnerability, which is countered by the second adaptation: a protective coating. Composed of sporopollenin, a durable biopolymer, this coating shields the spore from desiccation, UV radiation, and microbial attacks, ensuring its viability until it lands in a suitable habitat.

Consider the lifecycle implications of these adaptations. When a fern releases its spores, often in vast quantities, the lightweight nature of each spore increases the likelihood that at least some will reach fertile ground. For instance, a single fern can produce millions of spores annually, yet only a fraction will germinate successfully. The protective coating plays a critical role here, acting as a safeguard during the spore’s journey. Without it, spores would be susceptible to environmental stressors, drastically reducing their chances of survival. This dual strategy—lightweight for dispersal, protective for endurance—exemplifies how ferns have optimized their reproductive process to thrive in varied ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these adaptations can inform conservation efforts and horticulture practices. Gardeners cultivating ferns, for example, can mimic natural conditions by ensuring spores are dispersed in humid, shaded environments, where the protective coating can maintain spore integrity until germination. Additionally, researchers studying spore dispersal can use these adaptations as a model for developing bio-inspired technologies, such as lightweight, durable materials for environmental monitoring devices. By studying how ferns have mastered survival through these evolutionary traits, we gain insights into both biological resilience and potential applications in human innovation.

Comparatively, ferns’ spore adaptations contrast sharply with seed-producing plants, which invest energy in larger, nutrient-rich seeds. While seeds offer immediate resources for germination, they are heavier and require animals or gravity for dispersal. Ferns, on the other hand, prioritize quantity and durability, relying on wind and water to carry their spores over vast distances. This strategy reflects a trade-off between immediate survival and long-term dispersal, highlighting the diversity of reproductive approaches in the plant kingdom. By focusing on lightweight spores and protective coatings, ferns have carved out a niche that allows them to flourish in environments where seed-bearing plants might struggle.

In conclusion, the evolution of lightweight spores and protective coatings in ferns is a testament to nature’s ingenuity in solving complex survival challenges. These adaptations not only ensure the dispersal of spores across diverse landscapes but also enhance their resilience against environmental threats. Whether you’re a botanist, gardener, or simply an enthusiast of natural history, appreciating these strategies offers a deeper understanding of how ferns have persisted and thrived for millennia. By studying these mechanisms, we not only gain insights into plant biology but also uncover principles that can inspire solutions in fields ranging from materials science to conservation biology.

Exploring Legal Ways to Obtain Psychedelic Mushroom Spores Safely

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ferns spread their spores through a process called sporulation. The undersides of fern fronds contain structures called sori, which produce and release spores into the air. These lightweight spores are carried by wind or water to new locations.

Fern spores land in moist, shaded environments, such as forest floors, rock crevices, or damp soil. Once a spore lands in a suitable spot, it germinates into a tiny, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus, which eventually develops into a new fern plant.

While most ferns spread spores via wind dispersal, some species have adapted unique methods. For example, certain ferns have spores that are sticky or have wings, aiding in attachment or longer-distance travel. However, the basic mechanism of spore release from sori remains consistent across most fern species.