Mushrooms and trees share a complex and often symbiotic relationship, challenging the notion that mushrooms merely use trees for survival. While some mushrooms, like certain parasitic species, can harm trees by extracting nutrients, the majority engage in mutualistic partnerships known as mycorrhizal associations. In these relationships, mushrooms help trees absorb water and essential nutrients from the soil, while trees provide mushrooms with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. This interdependence highlights a fascinating ecological dynamic where mushrooms and trees rely on each other for growth and survival, rather than one simply exploiting the other.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Symbiotic Relationship | Mushrooms often form mutualistic relationships with trees, known as mycorrhizal associations, where the fungus helps the tree absorb nutrients (e.g., phosphorus, nitrogen) in exchange for carbohydrates from the tree. |

| Nutrient Exchange | Trees provide mushrooms with sugars (photosynthates), while mushrooms enhance the tree's access to soil nutrients and water. |

| Tree Health | Mushrooms can improve tree health by increasing nutrient uptake, enhancing resistance to pathogens, and promoting root growth. |

| Ecosystem Role | Mushrooms act as decomposers, breaking down dead wood and returning nutrients to the soil, benefiting both trees and the ecosystem. |

| Species Specificity | Certain mushroom species are specific to particular tree species, forming specialized mycorrhizal relationships. |

| Carbon Sequestration | Mycorrhizal networks involving mushrooms and trees play a role in carbon sequestration, storing carbon in the soil. |

| Forest Dependency | Many mushroom species rely on trees for habitat and nutrients, making them dependent on forested environments. |

| Wood Decay | Some mushrooms decompose dead or dying trees, recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. |

| Communication Network | Mycorrhizal fungi create underground networks (the "Wood Wide Web") that allow trees to share resources and signals, facilitated by mushrooms. |

| Biodiversity Support | Mushrooms associated with trees contribute to forest biodiversity by supporting various plant and animal species. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Symbiotic Relationships: Mushrooms form mutualistic mycorrhizal associations with trees, aiding nutrient exchange

- Decomposition Role: Saprotrophic mushrooms break down dead trees, recycling nutrients in ecosystems

- Tree Health Impact: Mycorrhizal networks enhance tree resilience against diseases and environmental stress

- Forest Communication: Mushrooms facilitate chemical signaling between trees via underground networks

- Resource Competition: Some mushrooms compete with trees for nutrients and water in soil

Symbiotic Relationships: Mushrooms form mutualistic mycorrhizal associations with trees, aiding nutrient exchange

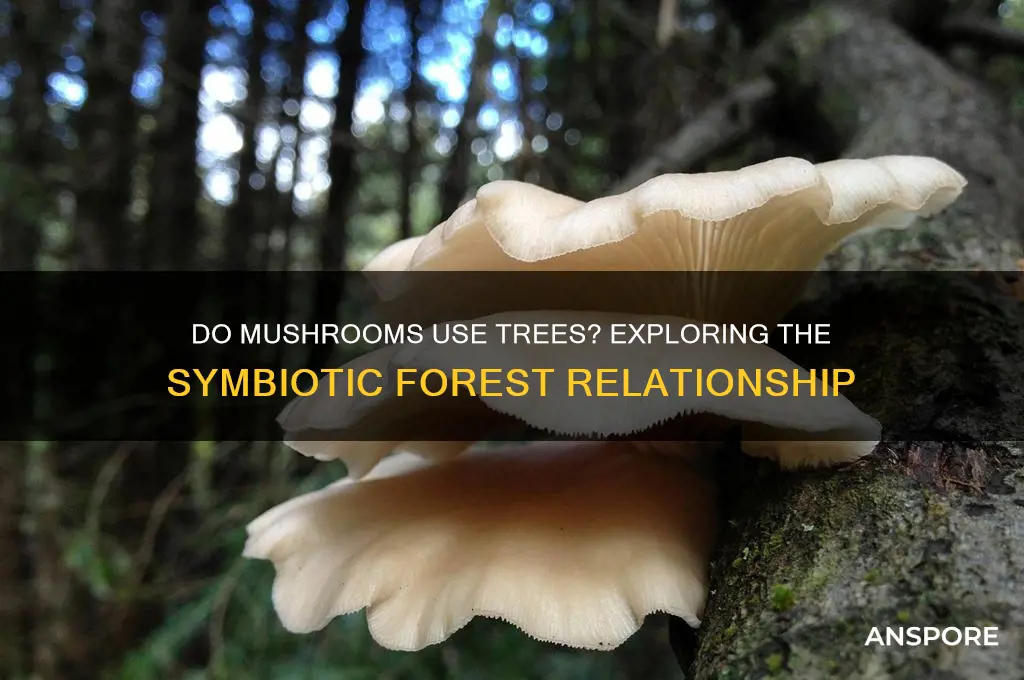

Beneath the forest floor, a hidden network thrives—a partnership so intricate it sustains entire ecosystems. Mushrooms, often overlooked, form mutualistic mycorrhizal associations with trees, creating a symbiotic relationship that is both ancient and essential. This underground alliance allows trees to access nutrients they couldn’t otherwise obtain, while mushrooms receive carbohydrates produced by the tree’s photosynthesis. It’s a give-and-take that highlights nature’s ingenuity, proving that even the most unlikely collaborators can thrive together.

Consider the process: tree roots, limited in their reach, struggle to absorb essential nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen from the soil. Enter mycorrhizal fungi, whose vast, thread-like hyphae extend far beyond the tree’s root system. These fungal networks act as extensions of the tree’s roots, efficiently scavenging nutrients and delivering them to the host plant. In return, the tree shares up to 20% of the sugars it produces through photosynthesis, fueling the fungus’s growth. This exchange is so effective that some studies suggest up to 90% of land plants rely on mycorrhizal fungi for optimal health.

To observe this relationship in action, look no further than the forest floor. The presence of mushrooms near trees isn’t coincidental—it’s a visible sign of this underground partnership. For gardeners or forest stewards, fostering this symbiosis can be practical. Introducing mycorrhizal inoculants to young trees or disturbed soil can enhance nutrient uptake, particularly in nutrient-poor environments. For example, applying 5–10 grams of mycorrhizal spores per tree during planting can significantly improve root development and overall tree health within the first growing season.

However, this relationship isn’t without its vulnerabilities. Disturbances like deforestation, soil compaction, or excessive fungicide use can disrupt mycorrhizal networks, weakening both fungi and trees. Climate change poses another threat, as shifts in temperature and precipitation patterns may alter the delicate balance of this symbiosis. Protecting these associations requires mindful land management practices, such as minimizing soil disturbance and preserving diverse fungal habitats.

In essence, the mutualistic bond between mushrooms and trees is a testament to nature’s interdependence. By understanding and nurturing this relationship, we can support healthier forests, more resilient ecosystems, and even improve agricultural practices. It’s a reminder that even the most hidden partnerships can have profound, far-reaching impacts—and that sometimes, the best collaborations are the ones we least expect.

Do Mushrooms Use Chemosynthesis? Unraveling Their Unique Energy Source

You may want to see also

Decomposition Role: Saprotrophic mushrooms break down dead trees, recycling nutrients in ecosystems

Saprotrophic mushrooms are nature’s recyclers, silently dismantling dead trees into their elemental components. Unlike parasites or mutualists, these fungi don’t exploit living trees; instead, they specialize in decomposition, targeting lignin and cellulose—tough plant materials most organisms can’t break down. This process begins when mushroom mycelium infiltrates dead wood, secreting enzymes that dissolve complex polymers into simpler sugars, amino acids, and minerals. Without saprotrophs, forests would be buried under layers of undecomposed timber, starving ecosystems of the nutrients needed for new growth.

Consider the practical implications for forest management. Leaving dead trees (snags or logs) in place fosters saprotrophic activity, enriching soil fertility over time. For instance, the oyster mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*) excels at decomposing hardwoods, converting up to 40% of a log’s mass into fungal biomass and nutrients within 1-2 years. Landowners can mimic this by creating "nurse logs" in gardens or reforestation sites, strategically placing fallen timber to accelerate nutrient cycling. Caution: avoid removing all deadwood, as this disrupts habitats for insects, birds, and other fungi dependent on decaying matter.

The efficiency of saprotrophic mushrooms varies by species and environment. For example, *Trametes versicolor* (turkey tail) thrives in cooler, moist conditions, while *Fomes fomentarius* (tinder fungus) prefers drier climates. Temperature and humidity dictate decomposition speed: optimal ranges (50-70°F, 60-80% humidity) can halve breakdown time compared to extremes. Gardeners can replicate these conditions by mulching around logs or shading them to retain moisture, ensuring fungi work at peak capacity.

From a conservation standpoint, protecting saprotrophic fungi is critical for ecosystem resilience. Disturbances like excessive logging or fungicide use decimate these communities, slowing nutrient return and weakening forest health. A study in the Pacific Northwest found that old-growth forests with intact fungal networks had 30% higher soil nitrogen levels than managed stands. To support these fungi, advocate for policies preserving deadwood and limiting chemical inputs in forestry and agriculture.

Finally, saprotrophic mushrooms offer a model for sustainable practices. Mycoremediation—using fungi to degrade pollutants—draws directly from their decomposition abilities. For instance, *Stropharia rugosoannulata* (wine cap stropharia) breaks down woody debris while filtering soil contaminants. Homeowners can cultivate this species in wood chip beds, simultaneously growing edible mushrooms and improving soil structure. By understanding and harnessing saprotrophs, we transform waste into resources, mirroring nature’s circular economy.

Do Mushrooms Photosynthesize? Unveiling Their Unique Energy-Harvesting Secrets

You may want to see also

Tree Health Impact: Mycorrhizal networks enhance tree resilience against diseases and environmental stress

Beneath the forest floor, a hidden network thrives—mycorrhizal fungi, often associated with mushrooms, form intricate alliances with tree roots. This symbiotic relationship isn’t just a passive exchange; it’s a dynamic partnership that bolsters tree resilience against diseases and environmental stressors. By colonizing root systems, these fungi create a vast underground web that facilitates nutrient sharing, water uptake, and chemical signaling between trees. This interconnectedness acts as a natural defense mechanism, enabling trees to withstand threats more effectively than they could alone.

Consider the practical implications of this network. Studies show that trees connected via mycorrhizal fungi exhibit greater resistance to pathogens like *Phytophthora* and *Armillaria*. For instance, in a managed forest, inoculating young saplings with specific mycorrhizal species can reduce disease incidence by up to 40%. Similarly, during drought conditions, this fungal network redistributes water from healthier to stressed trees, mitigating the impact of water scarcity. Gardeners and foresters can leverage this by selecting native mushroom species to cultivate, ensuring compatibility with local tree species for optimal benefits.

The role of mycorrhizal networks extends beyond disease and drought resistance. They also enhance nutrient absorption, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, which are critical for tree growth. For example, in nutrient-poor soils, trees connected to these networks can access up to 80% more phosphorus than those without fungal partners. This efficiency reduces the need for synthetic fertilizers, making mycorrhizal fungi an eco-friendly solution for sustainable forestry and agriculture. To harness this, landowners can introduce mycorrhizal inoculants during planting, ensuring young trees establish strong fungal connections early.

However, the effectiveness of mycorrhizal networks depends on environmental conditions and fungal diversity. Overuse of fungicides or soil disturbance can disrupt these networks, diminishing their protective benefits. To preserve this natural system, avoid excessive tilling and opt for organic pest management practices. Additionally, planting a variety of tree species fosters diverse fungal communities, enhancing the network’s resilience. For urban planners, incorporating native trees and mushrooms into green spaces can create self-sustaining ecosystems that thrive with minimal intervention.

In essence, mycorrhizal networks are not just a biological curiosity but a practical tool for improving tree health. By understanding and nurturing this underground alliance, we can enhance forest resilience, reduce disease outbreaks, and promote sustainable land management. Whether you’re a forester, gardener, or conservationist, integrating mycorrhizal fungi into your practices can yield long-term benefits for both trees and the ecosystems they support.

Einstein and Mushrooms: Unraveling the Psychedelic Genius Myth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Forest Communication: Mushrooms facilitate chemical signaling between trees via underground networks

Beneath the forest floor lies a hidden world of communication, where mushrooms act as the messengers in a complex network that connects trees. This underground system, often referred to as the "Wood Wide Web," is facilitated by mycorrhizal fungi, which form symbiotic relationships with tree roots. Through this network, trees exchange chemical signals, nutrients, and even warnings about threats like pests or drought. Mushrooms, as the fruiting bodies of these fungi, play a crucial role in maintaining and amplifying this communication, ensuring the forest functions as a cohesive ecosystem.

To understand how this works, imagine a tree under attack by insects. Instead of suffering in isolation, it releases chemical distress signals into the fungal network. These signals are swiftly transmitted to neighboring trees, which can then activate their defenses in response. For example, some trees release toxins to deter pests or increase their production of defensive compounds. This process is not just theoretical; studies have shown that trees connected by mycorrhizal networks are more resilient to stressors than those standing alone. Practical applications of this knowledge include forest management strategies that preserve fungal networks to enhance tree health and ecosystem stability.

From a comparative perspective, this fungal-mediated communication is akin to the internet, with mushrooms acting as routers and trees as users exchanging information. However, unlike the internet, this network is entirely biological and operates on a scale that spans entire forests. The efficiency of this system is remarkable: nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus are shared between trees, often benefiting younger or shaded trees that struggle to photosynthesize. For instance, older, more established trees can "donate" up to 20% of their carbon to saplings, fostering the next generation of forest growth. This interdependence highlights the critical role of mushrooms in sustaining forest ecosystems.

For those interested in harnessing this natural phenomenon, preserving fungal networks is key. Avoid tilling or compacting soil, as this disrupts the delicate hyphae (fungal threads) that form the network. Planting native tree species also supports mycorrhizal fungi, as these species have co-evolved to form strong symbiotic relationships. Additionally, reducing pesticide use is essential, as chemicals can harm the fungi and, by extension, the entire communication system. By adopting these practices, landowners and forest managers can promote healthier, more resilient forests.

In conclusion, mushrooms are not passive beneficiaries of trees but active facilitators of forest communication. Their role in the underground network underscores the interconnectedness of forest ecosystems and offers valuable lessons for sustainable land management. By understanding and protecting this hidden system, we can ensure forests continue to thrive, communicate, and support life above and below the ground.

Colorado's Psychedelic Shift: Recreational Mushrooms Legalized or Still Illegal?

You may want to see also

Resource Competition: Some mushrooms compete with trees for nutrients and water in soil

Beneath the forest floor, a silent battle rages for the very essence of life: nutrients and water. While trees tower above, their roots delve deep into the soil, seeking sustenance to fuel their growth. Yet, they are not alone in this quest. Certain mushrooms, often perceived as symbiotic partners, can become fierce competitors, siphoning off resources that trees desperately need. This dynamic, though hidden, shapes the health and balance of entire ecosystems.

Consider the case of *Armillaria* species, commonly known as honey fungi. These mushrooms form extensive underground networks called mycelia, which can stretch for acres. While they often decompose dead wood, they can also parasitize living trees, tapping into their root systems. This dual role—both decomposer and competitor—highlights the complexity of fungal behavior. As *Armillaria* extracts nutrients and water from the tree’s roots, it weakens the tree, making it more susceptible to stress, disease, and even death. In dense forests, this competition can lead to localized die-offs, altering the landscape over time.

To mitigate this resource competition, forest managers employ strategies such as selective thinning and soil amendments. Thinning reduces tree density, easing the demand on limited nutrients and water. Adding organic matter to the soil can also improve its fertility, giving trees a competitive edge. For gardeners or landowners, monitoring for signs of fungal competition—such as yellowing leaves, stunted growth, or mushroom clusters at the base of trees—is crucial. Early intervention, like removing infected trees or applying fungicides, can prevent further spread.

Yet, this competition is not inherently destructive. It is a natural process that drives adaptation and resilience in both trees and fungi. Some tree species have evolved defenses, such as thick bark or chemical compounds that deter fungal invasion. Similarly, certain mushrooms have developed mechanisms to coexist without harming their hosts. Understanding this delicate balance allows us to appreciate the intricate relationships within ecosystems and informs sustainable practices that support both flora and fungi.

In essence, the resource competition between mushrooms and trees is a testament to the fierce yet beautiful struggle for survival in nature. By observing and managing this dynamic, we can foster healthier forests and gardens, ensuring that both trees and mushrooms thrive in their shared habitat. Whether you’re a forester, gardener, or nature enthusiast, recognizing this hidden contest offers valuable insights into the interconnectedness of life beneath our feet.

Were Ancient Mushrooms Gigantic? Unveiling the Mystery of Prehistoric Fungi

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, many mushrooms form symbiotic relationships with trees through mycorrhizal associations, where the mushrooms help trees absorb water and nutrients in exchange for carbohydrates produced by the tree.

Yes, mushrooms can grow in various environments, including soil, decaying wood, and even manure, depending on the species. Not all mushrooms rely on trees for survival.

It depends. Some mushrooms, like mycorrhizal fungi, benefit trees, while others, such as parasitic fungi, can weaken or kill trees by feeding on their tissues.