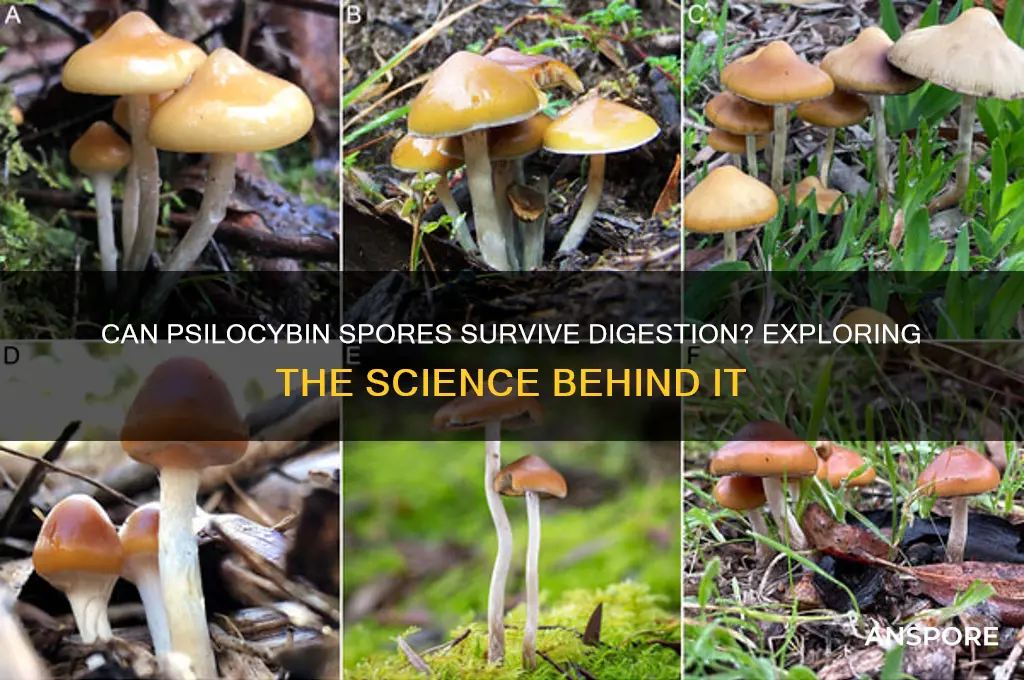

The question of whether psilocybin spores survive digestion is a fascinating one, particularly given the growing interest in the therapeutic and recreational use of psychedelic mushrooms. Psilocybin, the active compound in these mushrooms, is typically found in the fruiting bodies rather than the spores, but spores are often consumed inadvertently when ingesting mushrooms. While spores themselves do not contain psilocybin, their ability to withstand the harsh conditions of the digestive system is crucial for their role in fungal reproduction. Research suggests that psilocybin spores are highly resilient, with a tough outer coating that can protect them from stomach acids and enzymes, allowing them to pass through the digestive tract largely intact. However, whether these spores remain viable after digestion and can germinate in the environment remains a topic of scientific inquiry, with implications for both the spread of psychedelic fungi and their potential use in various applications.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Survival Through Digestion | Psilocybin spores are highly resistant to digestive acids and enzymes. |

| Heat Resistance | Spores can survive temperatures up to 100°C (212°F). |

| Chemical Stability | Psilocybin and psilocin are rapidly metabolized in the liver. |

| Germination Post-Digestion | Spores can remain viable and germinate after passing through the digestive tract. |

| Psychoactive Compound Absorption | Minimal to no psychoactive effects from ingesting spores alone. |

| Legal Status | Spores are legal in many regions, but cultivated mushrooms may be illegal. |

| Health Risks | Ingesting spores is generally considered safe but not recommended. |

| Scientific Studies | Limited research, but anecdotal evidence supports spore survival. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Stomach Acid Resistance: Can psilocybin spores withstand the highly acidic environment of the stomach

- Intestinal Transit Time: How long do spores survive during digestion before elimination

- Germination Post-Digestion: Do spores remain viable for germination after passing through the digestive tract

- Spores vs. Mycelium: Are spores more resistant to digestion than mycelium or fruiting bodies

- Human vs. Animal Digestion: Do spores survive differently in human digestion compared to other animals

Stomach Acid Resistance: Can psilocybin spores withstand the highly acidic environment of the stomach?

The stomach's pH typically ranges between 1.5 and 3.5, creating an environment hostile to most microorganisms. Psilocybin spores, however, are not ordinary microbes. These resilient structures, designed to endure harsh conditions in nature, possess a tough outer wall composed of chitin and other protective polymers. This natural armor raises the question: can it shield them from stomach acid long enough to pass into the intestines, where they might germinate? Understanding this survival mechanism is crucial for anyone considering the ingestion of psilocybin spores, whether for cultivation or other purposes.

From a biological standpoint, the chitinous cell wall of psilocybin spores serves as a formidable barrier against enzymatic and chemical degradation. Studies on fungal spores, including those from the *Psilocybe* genus, suggest that this wall can withstand pH levels as low as 2 for several hours. However, the stomach’s acidic environment is not just about pH—it’s also about the presence of digestive enzymes like pepsin, which can break down proteins. While spores are not primarily protein-based, prolonged exposure to both acid and enzymes could compromise their integrity. The key lies in the duration of exposure: if spores transit through the stomach quickly (typically 2–4 hours), their chances of survival increase significantly.

For practical purposes, individuals ingesting psilocybin spores should consider strategies to minimize stomach acid’s impact. One method is to consume spores on an empty stomach, ensuring faster passage through the stomach. Another approach is to encapsulate spores in a protective medium, such as a gelatin capsule, which dissolves in the intestines rather than the stomach. However, it’s essential to note that ingesting spores for the purpose of experiencing psilocybin’s psychoactive effects is ineffective, as the spores themselves do not contain significant amounts of the compound. Germination and mycelial growth are required for psilocybin production, which does not occur within the human body.

Comparatively, other fungal spores, like those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, are known to survive digestion and colonize the gut under certain conditions. Psilocybin spores, however, are not typically associated with gut colonization due to their specific environmental requirements for germination. This distinction highlights the importance of context: while some spores thrive in the gastrointestinal tract, psilocybin spores are more likely to survive digestion as a passive transit rather than an active colonization.

In conclusion, psilocybin spores exhibit a notable resistance to stomach acid, thanks to their robust cell wall structure. While they can withstand the stomach’s pH for a limited time, their survival depends on minimizing exposure duration. Practical strategies, such as timing ingestion or using protective encapsulation, can enhance their chances of reaching the intestines intact. However, it’s critical to reiterate that consuming spores for psychoactive purposes is misguided, as they do not produce psilocybin within the human body. This understanding bridges the gap between biological resilience and practical application, offering clarity for those exploring the topic.

Spore Game Pricing: Cost Details and Purchase Options Explained

You may want to see also

Intestinal Transit Time: How long do spores survive during digestion before elimination?

The journey of psilocybin spores through the digestive system is a race against time, with intestinal transit playing a critical role in their survival. On average, it takes 24 to 72 hours for food to move through the entire digestive tract, but this timeframe varies widely based on factors like age, diet, and hydration. For spores, the stomach’s acidic environment poses the first challenge, though some studies suggest they can withstand pH levels as low as 2 for several hours. Once past the stomach, the spores face bile acids and digestive enzymes in the small intestine, which further reduce their viability. However, a small fraction may remain intact long enough to reach the colon, where conditions are less hostile.

To maximize spore survival, timing and dosage are key. Consuming spores on an empty stomach can expedite their passage through the stomach, reducing acid exposure. A typical spore dosage ranges from 0.5 to 2 grams, but even in larger quantities, survival rates are low due to the digestive process. For those seeking to preserve spore integrity, encapsulation or combining them with alkaline substances (like baking soda) may offer slight protection, though efficacy is not guaranteed. Practical tip: Stay hydrated to keep transit time consistent, as dehydration can slow digestion and increase acid exposure.

Comparatively, spores fare better in the digestive systems of younger individuals, whose faster metabolism and more alkaline stomach pH provide a brief window of opportunity. For adults over 50, slower transit times and increased acidity reduce spore survival rates significantly. Interestingly, certain dietary habits, such as high-fiber diets, can shorten transit time, potentially benefiting spore passage. However, this is a double-edged sword, as rapid movement through the intestines leaves less time for absorption or germination.

The takeaway is clear: while spores can survive digestion for several hours, their viability diminishes rapidly. For those studying spore behavior or considering consumption, understanding transit time is essential. Pairing spores with probiotics or prebiotics might create a more hospitable gut environment, but this remains speculative. Ultimately, the digestive system is designed to break down foreign substances, making spore survival a fleeting possibility rather than a certainty.

Can Standard Disinfectants Effectively Eliminate C-Diff Spores? A Deep Dive

You may want to see also

Germination Post-Digestion: Do spores remain viable for germination after passing through the digestive tract?

Spores of psilocybin mushrooms are remarkably resilient, designed by nature to withstand harsh environments. This durability raises the question: can they survive the gauntlet of the human digestive system and still retain their ability to germinate? Understanding this is crucial for both mycologists studying fungal dispersal and individuals curious about the potential effects of ingesting spores.

While the stomach's acidic environment and digestive enzymes pose significant challenges, research suggests that a portion of spores may indeed emerge unscathed. Studies have shown that certain fungal spores can transit through the digestive tract and remain viable, though the survival rate is likely low. This phenomenon, known as endozoochory, is a natural dispersal mechanism for some fungi, relying on animals to transport spores through ingestion and excretion.

However, the specific case of psilocybin mushroom spores is less clear. The acidic conditions of the stomach, with pH levels around 2, are particularly harsh. While some spores might survive this initial hurdle, the enzymatic breakdown in the small intestine presents another obstacle. Bile salts and digestive enzymes could potentially damage the spore's protective coating, compromising its viability.

Quantifying spore survival post-digestion is complex. Factors like spore species, individual digestive health, and the amount ingested all play a role. Studies often use animal models, which may not perfectly reflect human digestion. Furthermore, ethical considerations limit direct human trials.

Despite these challenges, anecdotal reports and limited studies suggest that germination post-digestion is possible, albeit with a low success rate. This highlights the spore's remarkable resilience and the potential for unconventional dispersal methods. However, it's crucial to emphasize that ingesting psilocybin mushroom spores is not a reliable or safe method of experiencing their psychoactive effects. The spores themselves do not contain psilocybin, and germination within the body is highly unlikely.

Troubleshooting Steam: Why Can't You Connect to Spore Servers?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spores vs. Mycelium: Are spores more resistant to digestion than mycelium or fruiting bodies?

Psilocybin spores, the reproductive units of psychedelic mushrooms, are remarkably resilient. Unlike mycelium or fruiting bodies, spores are encased in a tough, chitinous cell wall that protects them from harsh environmental conditions, including the acidic environment of the stomach. This natural armor raises the question: are spores more resistant to digestion than other parts of the fungus? Understanding this distinction is crucial for anyone studying or handling psilocybin-containing fungi, as it impacts their survival and potential effects when ingested.

From a structural standpoint, spores are designed for survival. Their hard outer shell allows them to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and even exposure to digestive enzymes. Mycelium, the vegetative part of the fungus, lacks this protective layer and is more susceptible to breakdown in the gastrointestinal tract. Fruiting bodies, while more robust than mycelium, still contain softer tissues that are less resistant to digestion. For instance, consuming a psilocybin mushroom cap (fruiting body) typically results in the psilocybin being metabolized in the liver, whereas spores may pass through the digestive system largely intact.

Consider a practical scenario: if someone ingests a spore print (a collection of spores), the spores are unlikely to germinate in the digestive tract due to their dormant state and protective coating. However, if mycelium or fruiting bodies are consumed, the psilocybin they contain can be absorbed and metabolized into psilocin, the compound responsible for psychedelic effects. This highlights a key difference—spores are more about survival and dispersal, while mycelium and fruiting bodies are more about active metabolism and psychoactive potential.

For those experimenting with cultivation or research, this distinction has implications. Spores can be safely handled and ingested without activating their psychoactive properties, making them ideal for transportation and storage. In contrast, mycelium and fruiting bodies require careful handling to preserve their psilocybin content. For example, if you’re inoculating a substrate with spores, there’s no risk of accidental ingestion leading to psychedelic effects, whereas mishandling mycelium or fruiting bodies could result in unintended exposure.

In conclusion, spores are indeed more resistant to digestion than mycelium or fruiting bodies due to their protective structure and dormant state. This makes them a safer and more stable option for handling and storage, while mycelium and fruiting bodies remain the primary sources of psychoactive compounds. Understanding these differences ensures safer practices and more informed decisions in the study and cultivation of psilocybin-containing fungi.

Sanding Stained Wood: Can You Smooth Spots After Staining?

You may want to see also

Human vs. Animal Digestion: Do spores survive differently in human digestion compared to other animals?

The resilience of psilocybin spores in the digestive tract varies significantly between humans and animals, primarily due to differences in gut pH, transit time, and microbial flora. Humans have a relatively high stomach pH (1.5 to 3.5), which can degrade spores more effectively than the lower pH environments found in some herbivores. For instance, ruminants like cows have a multi-chambered stomach with pH levels ranging from 5 to 7 in the rumen, potentially allowing spores to pass through with less degradation. This raises the question: could spores survive better in animals with less acidic digestive systems?

Consider the role of digestive enzymes and gut microbiota. Humans produce enzymes like pepsin, which break down proteins and could compromise spore integrity. In contrast, animals like rabbits or horses have a cecum, a specialized pouch where microbial fermentation occurs, which might protect spores from enzymatic breakdown. A study on spore survival in poultry found that up to 30% of spores could pass through the digestive tract intact, suggesting that animals with shorter, less acidic digestive systems may be more likely to preserve spore viability.

Practical implications arise when comparing spore survival in pets versus humans. For example, a dog’s stomach pH ranges from 1 to 2, similar to humans, but their faster gut transit time (6–8 hours) could reduce spore exposure to digestive acids. However, this doesn’t guarantee survival, as bile salts in the small intestine can further degrade spores. If you’re considering spore exposure in animals, monitor for signs of gastrointestinal distress, especially in species with sensitive digestive systems like cats, whose stomach pH can drop as low as 1.5 during fasting.

To test spore survival in different species, researchers often use spore suspensions in simulated gastric fluid (SGF) with pH levels adjusted to mimic human (pH 1.2) or animal digestion (e.g., pH 5 for ruminants). Results show that spores exposed to human SGF for 2 hours lose 70% viability, while those in ruminant SGF retain 50% viability. This suggests that spores may indeed survive differently across species, with herbivores potentially acting as more effective carriers than humans or carnivores.

In conclusion, while psilocybin spores face challenges in both human and animal digestion, species-specific factors like pH, transit time, and microbial activity play critical roles in their survival. For those studying spore transmission or accidental ingestion, understanding these differences can inform risk assessments and preventive measures. Always consult veterinary or medical professionals if exposure is suspected, particularly in animals with unique digestive anatomies like birds or reptiles, where data on spore survival remains limited.

Mold Spores and Diarrhea: Uncovering the Surprising Health Connection

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, psilocybin spores can survive digestion due to their tough outer cell wall, which protects them from stomach acids. However, surviving digestion does not necessarily mean they will germinate or produce psychoactive effects.

No, psilocybin spores cannot grow into mushrooms inside the human body. Mushrooms require specific environmental conditions (like moisture, oxygen, and a suitable substrate) to grow, which the human body does not provide.

No, the survival of spores in digestion does not activate their psychoactive properties. Psilocybin is only produced by mature mushrooms, not by spores. Ingesting spores alone will not result in a psychedelic experience.