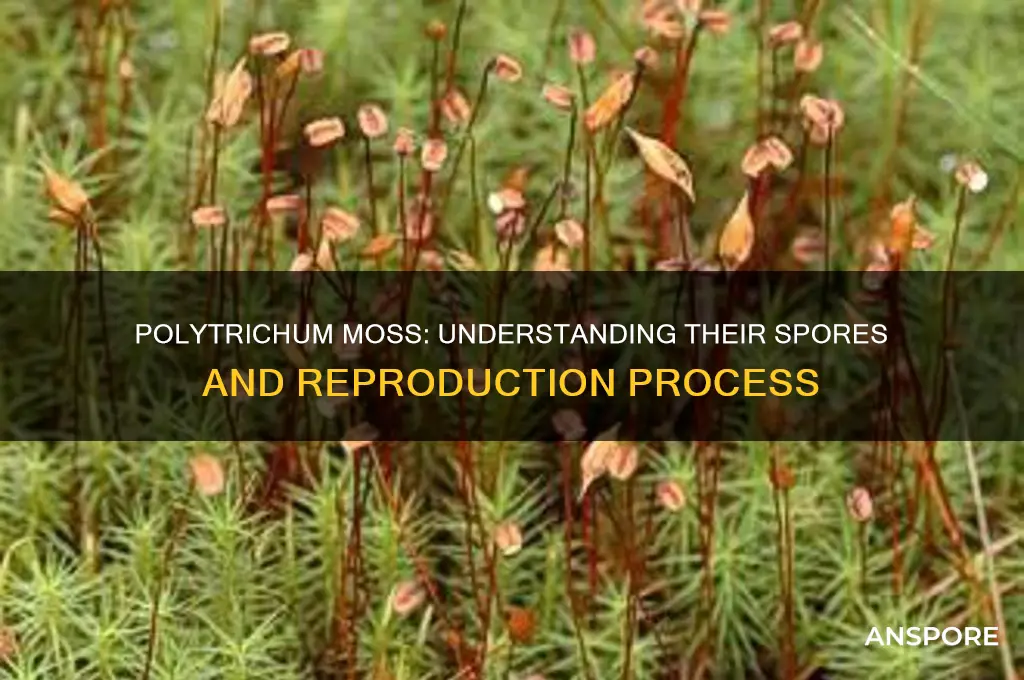

Polytrichum, commonly known as haircap moss, is a genus of mosses characterized by its distinctive, hair-like structures called awns on the leaf tips. These mosses are widely distributed and thrive in various environments, from moist soils to rocky outcrops. Like all mosses, Polytrichum reproduces via spores, which are produced in specialized structures called sporangia located at the tips of the sporophytes. The spores are dispersed by wind, allowing the moss to colonize new areas. This reproductive strategy is essential for the survival and propagation of Polytrichum species, ensuring their persistence in diverse ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do Polytrichum have spores? | Yes |

| Type of spores | Diploid (produced in sporangia) |

| Sporophyte structure | Long, stalked structure with a capsule at the tip |

| Capsule function | Contains and disperses spores |

| Spore dispersal mechanism | Ejected through a peristome (teeth-like structures) |

| Life cycle stage | Spores are part of the alternation of generations (sporophyte phase) |

| Habitat | Moist, shady environments (e.g., forests, bogs) |

| Common species | Polytrichum commune (common haircap moss) |

| Ecological role | Soil stabilization, water retention, and nutrient cycling |

| Distinguishing feature | Rigid, hair-like structures (paraphyses) surrounding the sporophyte |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Polytrichum spore structure: Examines the unique, large spores with spiral ridges aiding wind dispersal

- Spore production process: Details how Polytrichum produce spores in capsules atop gametophytes

- Spore dispersal methods: Explains wind-driven dispersal via spiral ridges and capsule dehiscence

- Spore germination conditions: Highlights moisture, light, and temperature needs for spore germination

- Role of spores in lifecycle: Describes spores as the dispersal and survival stage in alternation of generations

Polytrichum spore structure: Examines the unique, large spores with spiral ridges aiding wind dispersal

Polytrichum, a genus of mosses, produces spores that are a marvel of natural engineering. These spores are notably larger than those of many other moss species, typically ranging from 20 to 40 micrometers in diameter. This size is not arbitrary; it plays a crucial role in their function and survival. Larger spores have a greater surface area, which, when combined with their unique structure, enhances their ability to disperse effectively. The key to this lies in the spiral ridges that adorn the spore’s surface, a feature that sets Polytrichum apart from many other mosses.

The spiral ridges on Polytrichum spores are not merely decorative; they serve a critical aerodynamic purpose. These ridges create turbulence as the spores move through the air, increasing their stability and allowing them to travel farther on wind currents. This adaptation is particularly advantageous in open habitats where Polytrichum often thrives, such as heathlands and woodlands. The ridges also reduce the spores’ terminal velocity, enabling them to remain airborne longer and increase their chances of reaching suitable substrates for germination. This structural innovation is a testament to the evolutionary ingenuity of Polytrichum in maximizing reproductive success.

To observe these spores, one can collect a mature Polytrichum plant with sporophytes (the spore-producing structures) and gently tap them onto a dark surface. Under a microscope, the spores’ large size and spiral ridges become immediately apparent. For educators or enthusiasts, this simple activity provides a tangible way to demonstrate the relationship between structure and function in plant reproduction. It also highlights the importance of microscopy in botany, as the intricate details of Polytrichum spores are invisible to the naked eye.

From a practical standpoint, understanding Polytrichum spore structure has implications for conservation and horticulture. The efficient wind dispersal mechanism allows Polytrichum to colonize disturbed areas quickly, making it a valuable species for soil stabilization and ecosystem restoration. Gardeners and landscapers can utilize this knowledge by incorporating Polytrichum into green roofs or erosion-prone areas, where its spores can naturally spread and establish new growth. However, care must be taken to avoid introducing Polytrichum to ecosystems where it might outcompete native species, as its robust dispersal abilities could lead to unintended ecological impacts.

In conclusion, the unique structure of Polytrichum spores—large size combined with spiral ridges—is a fascinating example of adaptation to wind dispersal. This feature not only ensures the species’ survival but also offers practical applications in environmental management. By examining these spores, we gain insights into the intricate ways plants have evolved to thrive in their environments, reminding us of the importance of studying even the smallest components of ecosystems.

Playing Spore on MacBook Air: Compatibility and Performance Guide

You may want to see also

Spore production process: Details how Polytrichum produce spores in capsules atop gametophytes

Polytrichum, commonly known as haircap moss, is a fascinating genus of mosses that showcases a unique and intricate spore production process. Unlike simpler mosses, Polytrichum develops specialized structures called sporophytes, which emerge from the gametophyte plant body. These sporophytes are not just mere extensions but are complex, multicellular structures designed for the sole purpose of spore production. At the apex of each sporophyte lies a capsule, a critical organ where spores are formed and eventually dispersed.

The spore production process begins with the fertilization of an egg within the archegonium, a female reproductive organ on the gametophyte. This fertilization results in the development of a diploid sporophyte, which grows upward, often reaching several centimeters in height. The sporophyte consists of a foot, which anchors it to the gametophyte and absorbs nutrients, a seta, which acts as a stalk, and the capsule at the top. Inside the capsule, spore mother cells undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. This step is crucial for maintaining the alternation of generations in the moss life cycle.

As the spores mature, the capsule undergoes a series of structural changes to facilitate spore release. The capsule is typically elongated and has a lid-like structure called the operculum. Beneath the operculum lies a ring of teeth called the peristome, which plays a vital role in spore dispersal. When the capsule is ready, the operculum falls off, exposing the peristome. The peristome teeth are hygroscopic, meaning they respond to changes in humidity by opening and closing. In dry conditions, the teeth straighten, allowing spores to be released gradually. When humidity increases, the teeth curl inward, preventing water from entering the capsule and protecting the remaining spores.

Practical observation of this process can be enhanced by collecting mature Polytrichum specimens and examining the capsules under a magnifying glass or microscope. Gently squeezing the capsule can simulate dry conditions, causing the peristome teeth to open and release a cloud of spores. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the mechanism of spore dispersal but also highlights the adaptability of Polytrichum to its environment. For educators or enthusiasts, documenting the stages of capsule development and spore release can provide valuable insights into the reproductive strategies of mosses.

In conclusion, the spore production process in Polytrichum is a remarkable example of evolutionary specialization. From the initial fertilization to the sophisticated mechanisms of spore release, each step is finely tuned to ensure the survival and propagation of the species. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation for the complexity of mosses but also underscores their ecological importance as pioneers in various habitats. Whether for academic study or personal curiosity, exploring the spore production of Polytrichum offers a window into the intricate world of bryophytes.

Peracetic Acid's Power: Can It Effectively Inactivate Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore dispersal methods: Explains wind-driven dispersal via spiral ridges and capsule dehiscence

Polytrichum, a genus of mosses, employs sophisticated mechanisms for spore dispersal, leveraging both structural adaptations and environmental forces. One of its most remarkable features is the presence of spiral ridges on the sporophyte capsule, which play a critical role in wind-driven dispersal. These ridges are not merely decorative; they are precisely engineered to interact with air currents, creating a twisting motion that aids in the release and scattering of spores. This design ensures that spores are not only expelled efficiently but also carried over greater distances, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats.

The process begins with capsule dehiscence, the splitting open of the sporophyte capsule when mature. This mechanism is triggered by changes in humidity, causing the capsule to dry and contract, eventually forcing it open. As the capsule dehisces, the spiral ridges act as miniature propellers, catching the wind and spinning the capsule. This rotation generates centrifugal force, propelling spores outward in a controlled yet widespread manner. The efficiency of this system highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of Polytrichum, optimizing spore dispersal with minimal energy expenditure.

To observe this process, one can collect mature Polytrichum sporophytes and place them in a dry environment to simulate natural conditions. Over time, the capsules will begin to dehisce, revealing the spiral ridges in action. For educational purposes, a magnifying glass or microscope can be used to examine the ridges and spores in detail. Practical tips include collecting samples during late summer or early autumn when sporophytes are most mature, and storing them in a well-ventilated container to preserve their structure.

Comparatively, Polytrichum’s spore dispersal method stands out among bryophytes. While many mosses rely on simple capsule rupture or passive release, Polytrichum’s spiral ridges and dehiscence mechanism demonstrate a higher level of complexity. This adaptation is particularly advantageous in open habitats where wind is a dominant force, such as heathlands or exposed soil. By harnessing wind energy, Polytrichum maximizes its reproductive success, ensuring spores reach diverse and distant locations.

In conclusion, the wind-driven dispersal of Polytrichum spores via spiral ridges and capsule dehiscence is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. This mechanism not only showcases the plant’s adaptability but also offers valuable insights for biomimicry in engineering and design. By studying such processes, we can develop more efficient systems for seed or particle dispersal in agriculture, ecology, and beyond. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, Polytrichum serves as a living example of how small-scale structures can achieve large-scale impacts.

Can Mold Spores Trigger Persistent Coughing? Understanding the Link

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Spore germination conditions: Highlights moisture, light, and temperature needs for spore germination

Polytrichum, a genus of mosses, indeed produces spores as part of their life cycle. These spores are essential for the plant's reproduction and dispersal. Understanding the conditions required for spore germination is crucial for anyone looking to cultivate Polytrichum or study its growth patterns. The process is highly dependent on three key environmental factors: moisture, light, and temperature, each playing a unique role in triggering and sustaining germination.

Moisture: The Catalyst for Life

Spores of Polytrichum require a consistently moist environment to initiate germination. Water acts as both a medium for nutrient absorption and a signal that conditions are favorable for growth. Research indicates that a relative humidity of 80–90% is optimal, with water potential values ranging from -0.5 to -1.0 MPa. In practical terms, this means maintaining a damp substrate, such as peat or soil, without allowing it to become waterlogged. Overwatering can lead to spore suffocation or fungal growth, which competes with the moss for resources. For best results, mist the substrate daily or use a humidity dome to retain moisture levels.

Light: A Subtle Yet Critical Factor

While Polytrichum spores do not require intense light to germinate, the presence of light influences the direction and rate of growth. Spores exposed to low to moderate light levels (approximately 50–200 μmol/m²/s) tend to germinate more uniformly. Interestingly, red and far-red light spectra have been shown to enhance germination rates, mimicking natural forest floor conditions. Avoid direct sunlight, as it can desiccate the spores or cause overheating. For indoor cultivation, fluorescent or LED grow lights set on a 12–16 hour photoperiod provide sufficient illumination without risking damage.

Temperature: The Goldilocks Zone

Temperature plays a pivotal role in spore germination, with Polytrichum spores exhibiting a preference for cool to moderate conditions. Optimal germination occurs between 15°C and 25°C (59°F–77°F), mirroring the temperate habitats where these mosses thrive. Temperatures below 10°C slow germination, while those above 30°C can inhibit it entirely. Consistency is key; fluctuations of more than 5°C within a 24-hour period can disrupt the process. For controlled environments, use heating mats or thermostats to maintain stable temperatures, ensuring spores remain within their ideal range.

Practical Tips for Successful Germination

To maximize germination success, combine these factors thoughtfully. Start by sterilizing the substrate to prevent contamination, then evenly disperse spores on the surface. Maintain moisture through regular misting, ensure indirect light exposure, and monitor temperature with precision. Patience is essential, as germination can take several weeks. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, documenting environmental conditions during each attempt provides valuable insights into optimizing growth. By mastering these conditions, one can unlock the fascinating world of Polytrichum cultivation and study.

Railgun vs. Spore Spewers: Can It Annihilate the Threat Effectively?

You may want to see also

Role of spores in lifecycle: Describes spores as the dispersal and survival stage in alternation of generations

Spores are the unsung heroes of the plant kingdom, particularly in the lifecycle of bryophytes like *Polytrichum*. These microscopic structures serve as the primary means of dispersal and survival, ensuring the species’ continuity across generations. In *Polytrichum*, spores are produced in the sporophyte generation, the diploid phase of its lifecycle, and are released into the environment to initiate new gametophytes, the haploid phase. This alternation of generations is a hallmark of bryophytes, and spores are the critical link between these stages. Without spores, *Polytrichum* would lack the ability to colonize new habitats or survive harsh environmental conditions, making them indispensable to the species’ persistence.

Consider the journey of a spore: once released from the sporophyte’s capsule, it is carried by wind, water, or animals to a suitable substrate. This dispersal mechanism allows *Polytrichum* to spread far beyond its parent plant, increasing genetic diversity and reducing competition for resources. Spores are remarkably resilient, capable of withstanding desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other environmental stresses. This survival stage is crucial, as it ensures that even if the parent plant perishes, the species can endure through its spores. For gardeners or researchers cultivating *Polytrichum*, understanding this resilience can inform strategies for propagation and conservation, such as storing spores in dry, cool conditions to preserve viability.

The production of spores in *Polytrichum* is a precise and energy-intensive process, highlighting their evolutionary significance. Sporophytes invest heavily in spore development, often at the expense of their own growth. This investment underscores the spore’s role as the species’ future. Each spore contains the genetic material necessary to develop into a new gametophyte, which will eventually produce gametes to start the cycle anew. For educators or hobbyists studying *Polytrichum*, observing spore release under a microscope can provide valuable insights into the plant’s reproductive strategy and the efficiency of its dispersal mechanisms.

Comparatively, spores in *Polytrichum* function similarly to seeds in vascular plants but with distinct advantages. Unlike seeds, spores are smaller, lighter, and produced in far greater quantities, maximizing dispersal potential. However, this comes with a trade-off: spores require specific environmental conditions, such as moisture and light, to germinate successfully. For those attempting to grow *Polytrichum* from spores, creating a humid, shaded environment with a substrate rich in organic matter can significantly enhance germination rates. This practical approach leverages the spore’s natural adaptations, ensuring successful establishment of new plants.

In conclusion, spores are not merely reproductive units in *Polytrichum* but are central to its lifecycle, serving as both dispersal agents and survival structures. Their role in the alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity, species continuity, and adaptability to changing environments. Whether you’re a botanist, educator, or enthusiast, appreciating the spore’s function offers a deeper understanding of *Polytrichum*’s ecological and evolutionary success. By studying or cultivating this bryophyte, one gains a tangible connection to the intricate mechanisms that sustain life in the plant kingdom.

Botulism Spores: Can They Cause Illness and Health Risks?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Polytrichum, a genus of mosses, produces spores as part of their reproductive cycle.

Polytrichum release spores from specialized structures called sporangia, located at the tips of their sporophytes, which are elevated by seta (stalk-like structures).

Polytrichum spores are similar in function to those of other mosses but are often larger and more distinctive in shape, aiding in their dispersal and germination.