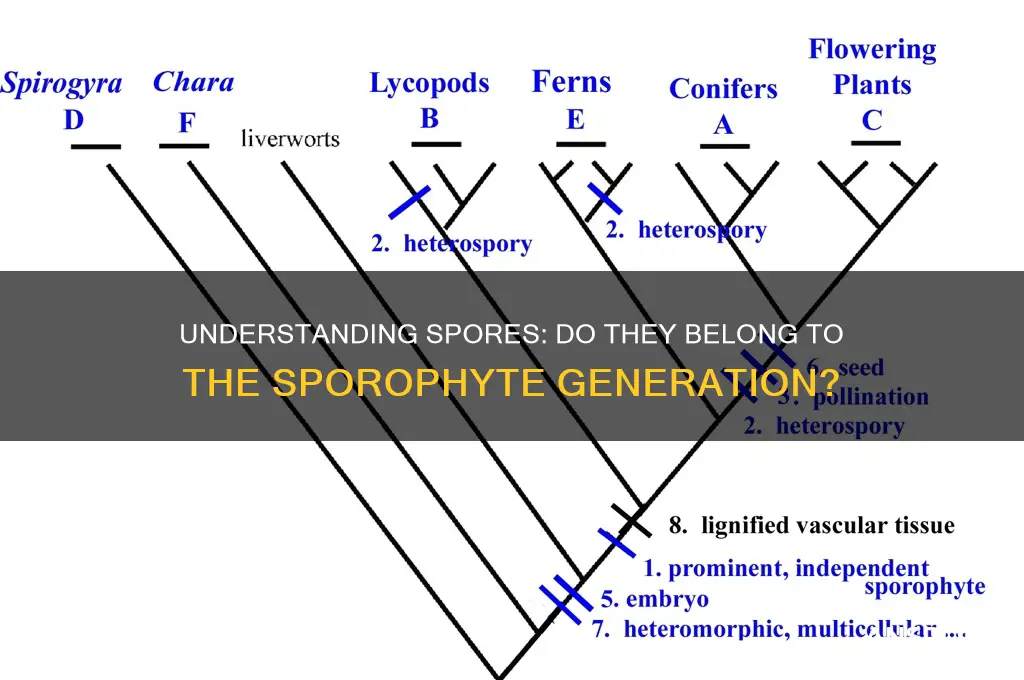

The question of whether spores belong to the sporophyte generation is central to understanding the life cycles of plants, particularly in bryophytes, ferns, and seed plants. In the alternation of generations, a characteristic feature of these organisms, two distinct phases exist: the sporophyte, which produces spores, and the gametophyte, which produces gametes. Spores are typically produced by the sporophyte through meiosis, a process that reduces the chromosome number, and they develop into gametophytes. Therefore, while spores are derived from the sporophyte generation, they are not part of it; instead, they represent the starting point of the gametophyte generation. This distinction highlights the intricate relationship between these two phases in the plant life cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Belonging Generation | Spores belong to the sporophyte generation in some plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) but to the gametophyte generation in others (e.g., liverworts, hornworts). |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are haploid cells produced by the sporophyte (diploid) generation via meiosis. |

| Function | Spores develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals to colonize new areas. |

| Examples | In ferns, spores grow into small, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli). In mosses, spores develop into thread-like protonema. |

| Alternation of Generations | Spores are part of the alternation of generations, cycling between sporophyte (diploid) and gametophyte (haploid) phases. |

| Dependency | Spores are dependent on moisture for germination and survival, as they lack vascular tissue. |

| Size | Spores are typically microscopic, ranging from 10 to 50 micrometers in diameter. |

| Wall Composition | Spores have a protective outer wall made of sporopollenin, a highly resistant polymer. |

| Longevity | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh environmental conditions. |

Explore related products

$7.98

What You'll Learn

- Sporophyte Dominance: Understanding the role of sporophytes in plant life cycles

- Spore Formation: How spores develop within the sporangia of sporophytes

- Germination Process: Spores sprouting into gametophytes, the alternate generation

- Life Cycle Phases: Alternation between sporophyte and gametophyte generations

- Evolutionary Significance: Why spores are key to plant survival and adaptation

Sporophyte Dominance: Understanding the role of sporophytes in plant life cycles

Spores are a fundamental part of the plant life cycle, but they do not belong to the sporophyte generation. Instead, spores are the product of the sporophyte—the spore-producing phase in the alternation of generations. This distinction is crucial for understanding sporophyte dominance, a phenomenon where the sporophyte generation is the more prominent and long-lived phase in vascular plants like ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. In these plants, the sporophyte invests significant energy in producing spores, which then develop into the gametophyte generation, a smaller and often short-lived phase responsible for sexual reproduction.

To grasp sporophyte dominance, consider the life cycle of a fern. The visible fern plant we see is the sporophyte, which produces spores via structures called sporangia. These spores germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli) that are often hidden from view. The gametophyte’s sole purpose is to produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction, which ultimately leads to the formation of a new sporophyte. This cycle highlights the sporophyte’s central role: it not only dominates in size and longevity but also drives the continuation of the species by producing the next generation’s starting point—the spores.

From an evolutionary perspective, sporophyte dominance is a key adaptation that has allowed vascular plants to thrive on land. The sporophyte’s robust structure provides stability and access to resources, enabling it to produce spores in large quantities. For example, a single fern frond can release thousands of spores, increasing the chances of successful colonization in diverse environments. In contrast, the gametophyte’s reduced size and dependency on moisture for reproduction limit its survival, making it less dominant in the life cycle. This imbalance underscores the sporophyte’s critical role in ensuring genetic diversity and species survival.

Practical observations of sporophyte dominance can guide horticulture and conservation efforts. For instance, when propagating ferns, gardeners focus on collecting and sowing spores rather than nurturing gametophytes, as the latter are delicate and short-lived. Similarly, in reforestation projects involving gymnosperms like pines, understanding sporophyte dominance helps prioritize the cultivation of seed-bearing trees (sporophytes) over their microscopic gametophyte counterparts. By recognizing the sporophyte’s primacy, we can develop strategies that align with natural processes, enhancing plant growth and ecosystem restoration.

In conclusion, while spores are essential to the plant life cycle, they are not part of the sporophyte generation but rather its reproductive output. Sporophyte dominance reflects an evolutionary strategy where the sporophyte invests heavily in spore production, ensuring the continuity of the species. This understanding not only deepens our appreciation of plant biology but also informs practical applications in horticulture and conservation. By focusing on the sporophyte’s role, we can better harness its strengths to sustain plant life in diverse environments.

Does Spore Effectively Work on Grass-Type Pokémon? A Detailed Analysis

You may want to see also

Spore Formation: How spores develop within the sporangia of sporophytes

Spores are the product of a complex developmental process that occurs within the sporangia of sporophytes, marking a critical phase in the life cycle of plants, particularly in ferns, mosses, and other non-seed vascular plants. This process, known as sporogenesis, involves the transformation of specialized cells into spores through meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity and the potential for new growth. Understanding how spores develop within the sporangia sheds light on the intricate balance between asexual and sexual reproduction in these organisms.

The formation of spores begins with the differentiation of sporogenous cells within the sporangium, a structure located on the sporophyte generation. These cells undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores. This reduction is essential for the alternation of generations, where the sporophyte (diploid) and gametophyte (haploid) phases alternate. In ferns, for example, each sporangium can produce hundreds to thousands of spores, depending on the species and environmental conditions. The sporangium’s wall plays a protective role, shielding the developing spores from desiccation and physical damage until they are mature and ready for dispersal.

Environmental cues, such as light, temperature, and humidity, influence the timing and efficiency of spore formation. For instance, in many fern species, spore development is accelerated under warm, humid conditions, while cooler temperatures may delay the process. Once mature, spores are released through an opening in the sporangium, often triggered by drying or mechanical stress. This release mechanism ensures widespread dispersal, increasing the chances of spores landing in suitable habitats for germination.

Practical observations of spore formation can be made through simple experiments. For example, collecting sporangia from mature fern fronds and examining them under a microscope reveals the intricate structure of the sporangium and the developing spores. By monitoring these structures over time, one can observe the progression from sporogenous cells to mature spores. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding but also highlights the precision and adaptability of plant reproductive strategies.

In conclusion, spore formation within the sporangia of sporophytes is a finely tuned process that bridges the gap between generations in the plant life cycle. By producing haploid spores through meiosis, sporophytes ensure genetic diversity and the continuity of their species. Whether observed in the wild or under a microscope, this process underscores the elegance and efficiency of nature’s reproductive mechanisms. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, studying spore formation offers valuable insights into the biology of plants and their survival strategies.

Can Rothia Mucilaginosa Form Spores? Exploring Its Reproductive Capabilities

You may want to see also

Germination Process: Spores sprouting into gametophytes, the alternate generation

Spores, the microscopic units of life, are the bridge between generations in the plant kingdom, particularly in bryophytes, ferns, and other non-seed plants. These resilient structures are produced by the sporophyte generation and are designed to disperse and survive in harsh conditions. When conditions become favorable, spores germinate, marking the transition to the gametophyte generation—a pivotal phase in the plant life cycle.

The Germination Process Unveiled

Germination begins when a spore absorbs water, triggering metabolic activity and breaking dormancy. This initial hydration is critical; without it, the spore remains inert. Once activated, the spore’s cell wall softens, allowing the emergence of a protonema or a filamentous structure in some species, such as mosses. This stage is delicate, requiring a balance of moisture, light, and temperature. For instance, fern spores often require indirect light and a humid environment to sprout successfully.

From Protonema to Gametophyte

As the protonema grows, it develops into the gametophyte, the sexual phase of the plant. In mosses, the protonema gives rise to leafy gametophores, while in ferns, it forms a heart-shaped prothallus. This transformation is nutrient-dependent; gametophytes are typically smaller and shorter-lived than sporophytes, relying on the environment for water and minerals. For optimal growth, maintain a substrate pH between 5.5 and 6.5, as acidity can hinder nutrient uptake.

Environmental Cues and Timing

Germination is highly sensitive to environmental cues. Light quality, for example, influences the direction and rate of growth in fern spores, with red light often promoting faster development. Temperature plays a dual role: while warmth accelerates germination, extreme heat can denature enzymes essential for the process. Ideal conditions vary by species; for instance, *Sphagnum* moss spores thrive in cooler, peat-rich environments, whereas tropical fern spores require higher temperatures.

Practical Tips for Successful Germination

To cultivate gametophytes from spores, start by sterilizing the substrate to prevent fungal contamination. Use a fine-grained medium like milled sphagnum or vermiculite, ensuring it remains consistently moist but not waterlogged. For ferns, scatter spores evenly on the surface and cover with a thin layer of plastic to retain humidity. Monitor daily, removing the cover once protonema appear to prevent rot. Patience is key; germination can take weeks, depending on the species and conditions.

The Alternate Generation Revealed

The gametophyte generation is the sexual phase, producing gametes that eventually form a new sporophyte. This alternation of generations is a cornerstone of plant evolution, ensuring genetic diversity through sexual reproduction. By understanding the germination process, we gain insight into the resilience and adaptability of plants, from the smallest moss to the tallest fern. This knowledge is not only academic but practical, aiding in conservation, horticulture, and the study of plant biology.

Do Spore Drops Impact Substrate Quality and Mushroom Yield?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Phases: Alternation between sporophyte and gametophyte generations

Spores are the cornerstone of the alternation of generations, a life cycle that defines many plants and algae. This cycle is a delicate dance between two distinct phases: the sporophyte and gametophyte generations. Each phase has its unique role, and understanding their interplay is crucial to grasping the complexity of plant reproduction.

The Sporophyte's Dominion: Imagine a towering tree, its branches heavy with leaves. This is the sporophyte generation, the dominant phase in many plant life cycles. The sporophyte is a diploid organism, meaning it carries two sets of chromosomes. Its primary function is to produce spores through a process called meiosis. These spores are not just any cells; they are the vehicles of dispersal, carrying the potential for new life. In ferns, for instance, the sporophyte produces spores on the underside of its fronds. Each spore is a miniature package of genetic material, ready to embark on a journey.

Spore Dispersal and Germination: Once released, spores are at the mercy of the wind, water, or other agents of dispersal. This phase is critical, as it allows plants to colonize new areas. Upon landing in a suitable environment, a spore germinates, giving rise to the gametophyte generation. This is where the life cycle takes an intriguing turn.

Gametophyte's Delicate Existence: The gametophyte generation is a haploid organism, carrying a single set of chromosomes. It is typically smaller and less conspicuous than the sporophyte. In bryophytes (mosses and liverworts), the gametophyte is the dominant generation, while in ferns and seed plants, it is often diminutive. The gametophyte's primary role is to produce gametes – sperm and eggs – through mitosis. In ferns, the gametophyte, known as a prothallus, is a small, heart-shaped structure that develops from a spore. It produces sperm, which require water to swim to the eggs, also produced by the prothallus. This dependence on water for fertilization is a key characteristic of non-seed plants.

The Union and Renewal: Fertilization occurs when a sperm fertilizes an egg, resulting in a diploid zygote. This zygote develops into a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. In seed plants, the process is more complex, involving the production of seeds, which protect the embryo and provide nutrients for early growth. The alternation of generations ensures genetic diversity, as spores are produced through meiosis, and fertilization involves the fusion of gametes from different individuals.

Understanding this alternation is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications. For instance, in agriculture, knowing the life cycle phases helps in breeding programs, where the goal is to produce plants with desirable traits. In conservation efforts, recognizing the vulnerability of certain phases, like the water-dependent fertilization in fern gametophytes, can guide strategies to protect species. The intricate dance between sporophyte and gametophyte generations is a testament to the elegance and complexity of plant life cycles, offering insights that are both scientifically fascinating and practically valuable.

Breathing C. Diff Spores: Risks, Prevention, and Air Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Significance: Why spores are key to plant survival and adaptation

Spores are the unsung heroes of plant evolution, serving as the bridge between generations and environments. In the life cycle of plants, particularly those with alternation of generations, spores belong to the sporophyte generation, the diploid phase that produces haploid spores through meiosis. This process is not just a biological curiosity; it is a strategic adaptation that has ensured the survival and diversification of plant species over millions of years. By producing spores, plants can disperse their genetic material over vast distances, colonize new habitats, and withstand harsh conditions that would otherwise be fatal to more developed life stages.

Consider the resilience of fern spores, which can remain dormant for years, waiting for the right conditions to germinate. This ability to delay development until environmental factors align—such as adequate moisture and light—is a survival mechanism honed by evolution. Similarly, the lightweight, aerodynamic design of spores allows them to travel on wind currents, a feature exploited by species like mosses and liverworts to populate remote or inhospitable areas. This dispersal capability is not just a passive trait but an active strategy that enhances genetic diversity and reduces competition among closely related individuals.

From an evolutionary standpoint, spores act as a genetic reset button. By transitioning from the sporophyte to the gametophyte generation, plants reduce their genetic load, minimizing the impact of deleterious mutations. This cyclical reduction in ploidy levels ensures that each generation starts anew, with a higher chance of adapting to changing environments. For instance, in gymnosperms and angiosperms, pollen grains (male spores) and embryo sacs (female spores) carry half the genetic material of their parent plants, allowing for rapid recombination and innovation during fertilization.

Practical applications of spore biology are evident in agriculture and conservation. Farmers and horticulturists harness the power of spores in seed banks, preserving genetic material for future use. For example, orchid seeds, which are essentially spores, are cultivated in sterile environments to propagate rare species. Conservationists use spore dispersal techniques to restore degraded ecosystems, such as reintroducing bryophyte species to damaged soil to improve water retention and nutrient cycling. These methods underscore the evolutionary significance of spores as tools for both survival and human intervention.

In conclusion, spores are not merely a stage in the plant life cycle; they are a testament to the ingenuity of evolution. Their role in dispersal, dormancy, and genetic renewal has enabled plants to thrive in diverse and challenging environments. By understanding and leveraging the unique properties of spores, we can address contemporary challenges, from food security to biodiversity loss, ensuring that the legacy of these microscopic powerhouses continues to shape life on Earth.

Unlocking Gut Health: Understanding Spore-Based Probiotics and Their Benefits

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, spores belong to the gametophyte generation. They are produced by the sporophyte through meiosis and develop into gametophytes.

Spores are haploid cells that germinate to form gametophytes, which then produce gametes (sperm and eggs) for sexual reproduction.

Spores are produced in the sporophyte generation through the process of meiosis, which reduces the chromosome number from diploid to haploid.

Yes, all plants with alternation of generations, including ferns, mosses, and seed plants, have a sporophyte generation that produces spores.