Spores, which are reproductive structures produced by various organisms such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria, are known for their resilience and ability to survive harsh environmental conditions. A key feature of spores is their protective outer layer, which plays a crucial role in their durability. One of the most significant components of this protective layer is the cell wall, a rigid structure that provides structural support and protection against external stressors. The presence of a cell wall in spores is essential for their ability to withstand desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other adverse conditions, making it a fundamental characteristic of these specialized cells. Understanding whether spores have cell walls is important for comprehending their survival mechanisms and their role in the life cycles of the organisms that produce them.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do spores have cell walls? | Yes |

| Type of cell wall | Typically composed of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides |

| Function of spore cell wall | Provides structural support, protection against environmental stresses (e.g., heat, desiccation, UV radiation), and prevents water loss |

| Thickness of spore cell wall | Generally thicker than vegetative cell walls, contributing to spore durability |

| Cell wall composition in bacterial spores | Contains peptidoglycan (murein) and additional layers like cortex and coat proteins |

| Cell wall composition in fungal spores | Primarily composed of chitin, glucans, and mannoproteins |

| Cell wall composition in plant spores | Contains sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer, in addition to cellulose and other polysaccharides |

| Role in spore dormancy | The cell wall helps maintain spore dormancy by regulating water and nutrient uptake |

| Resistance to degradation | Spore cell walls are highly resistant to enzymatic and chemical degradation, aiding long-term survival |

| Germination process | The cell wall must be modified or degraded for the spore to germinate and resume growth |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cell Wall Composition: Do spores have cell walls made of chitin, cellulose, or other materials

- Function of Cell Walls: How do spore cell walls protect against environmental stressors like heat and UV

- Thickness and Structure: Are spore cell walls thicker or differently structured compared to vegetative cells

- Cell Wall Formation: At what stage of spore development does the cell wall form

- Species Variations: Do all spore-producing organisms (e.g., fungi, bacteria) have cell walls in their spores

Cell Wall Composition: Do spores have cell walls made of chitin, cellulose, or other materials?

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain organisms, indeed possess cell walls, but their composition varies significantly across different species. Unlike the uniform cellulose-based walls of plants, spore cell walls are tailored to their unique roles in protection and dispersal. For instance, fungal spores, such as those from *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, have cell walls primarily composed of chitin, a tough polysaccharide also found in insect exoskeletons. This chitinous layer provides structural integrity and resistance to environmental stresses, enabling spores to survive harsh conditions like desiccation and extreme temperatures.

In contrast, bacterial spores, exemplified by those of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, feature cell walls with a distinct composition. These spores are encased in multiple layers, including a thick proteinaceous coat and an outer exosporium, but their core wall structure is not chitin-based. Instead, bacterial spore walls contain peptidoglycan, a polymer similar to that found in vegetative bacterial cells, though in a more cross-linked and dehydrated form. This composition contributes to their extraordinary durability, allowing them to withstand radiation, heat, and chemicals.

Plant spores, such as those from ferns or mosses, exhibit yet another variation in cell wall composition. Their walls are primarily composed of cellulose, the same material found in plant cell walls, but they also contain additional polymers like sporopollenin. This lipid-rich biopolymer forms a highly resistant outer layer, protecting the spore during its airborne journey and ensuring successful germination upon landing in a suitable environment. The presence of sporopollenin is a key factor in the longevity of plant spores, with some remaining viable for thousands of years.

Understanding these compositional differences is crucial for practical applications, such as developing antifungal agents or preserving historical artifacts contaminated with spores. For example, chitin-degrading enzymes like chitinases can be used to target fungal spores in agricultural settings, while bacterial spores may require autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure complete inactivation. Similarly, the unique properties of sporopollenin in plant spores make them valuable in paleobotanical studies, where their analysis provides insights into past climates and ecosystems. By recognizing the specific materials that compose spore cell walls, scientists and practitioners can devise more effective strategies for managing, studying, and utilizing these remarkable structures.

Are Ivy Spores Harmful? Uncovering the Truth About Ivy Spores

You may want to see also

Function of Cell Walls: How do spore cell walls protect against environmental stressors like heat and UV?

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain bacteria, fungi, and plants, are renowned for their ability to withstand extreme environmental conditions. Central to this survival capability is their cell wall, a robust and specialized structure that acts as the first line of defense against stressors like heat and UV radiation. Unlike the cell walls of vegetative cells, spore cell walls are composed of unique materials such as sporopollenin and dipicolinic acid, which confer exceptional durability and resistance. These components form a protective barrier that shields the spore’s genetic material and metabolic machinery from damage, ensuring long-term viability even in harsh environments.

One of the key mechanisms by which spore cell walls protect against heat stress is their ability to maintain structural integrity at high temperatures. Sporopollenin, a highly cross-linked biopolymer, provides a rigid framework that resists thermal degradation. This material acts like a natural insulator, minimizing heat penetration and preventing denaturation of proteins and nucleic acids within the spore. For example, bacterial endospores can survive temperatures exceeding 100°C for extended periods, a feat made possible by their specialized cell wall architecture. Similarly, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* species, rely on their cell walls to endure heat shocks that would destroy less protected cells.

UV radiation poses another significant threat to cellular structures, particularly DNA, which can sustain irreparable damage from UV-induced mutations. Spore cell walls combat this by incorporating pigments and compounds that absorb or scatter UV rays. For instance, melanin, a common component in fungal spore walls, acts as a natural sunscreen, dissipating UV energy as heat. Additionally, the thickness and density of spore cell walls reduce the penetration depth of UV radiation, further safeguarding the spore’s internal contents. This dual-layered protection—physical barrier plus UV-absorbing compounds—ensures that spores remain dormant yet viable even after prolonged exposure to sunlight.

Practical applications of spore cell wall resilience are found in industries such as food preservation and biotechnology. In food processing, heat-resistant bacterial spores like *Clostridium botulinum* are targeted for elimination through sterilization techniques (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes). Understanding the protective role of their cell walls helps optimize these processes to ensure safety. Similarly, in agriculture, fungal spores engineered with enhanced cell wall UV resistance could improve crop resilience in sun-exposed environments. For hobbyists or researchers culturing microorganisms, knowing that spores require more aggressive sterilization methods than vegetative cells can prevent contamination and ensure experimental accuracy.

In summary, spore cell walls are not merely passive structures but dynamic shields engineered by evolution to counter environmental extremes. Their composition and design provide a blueprint for developing synthetic materials with similar protective properties. Whether in nature or industry, the function of spore cell walls in resisting heat and UV radiation underscores their critical role in the survival and dissemination of these microscopic powerhouses. By studying these mechanisms, we unlock insights into both biological resilience and practical innovations.

Can Botulism Spores Survive Fermentation? Uncovering the Risks and Facts

You may want to see also

Thickness and Structure: Are spore cell walls thicker or differently structured compared to vegetative cells?

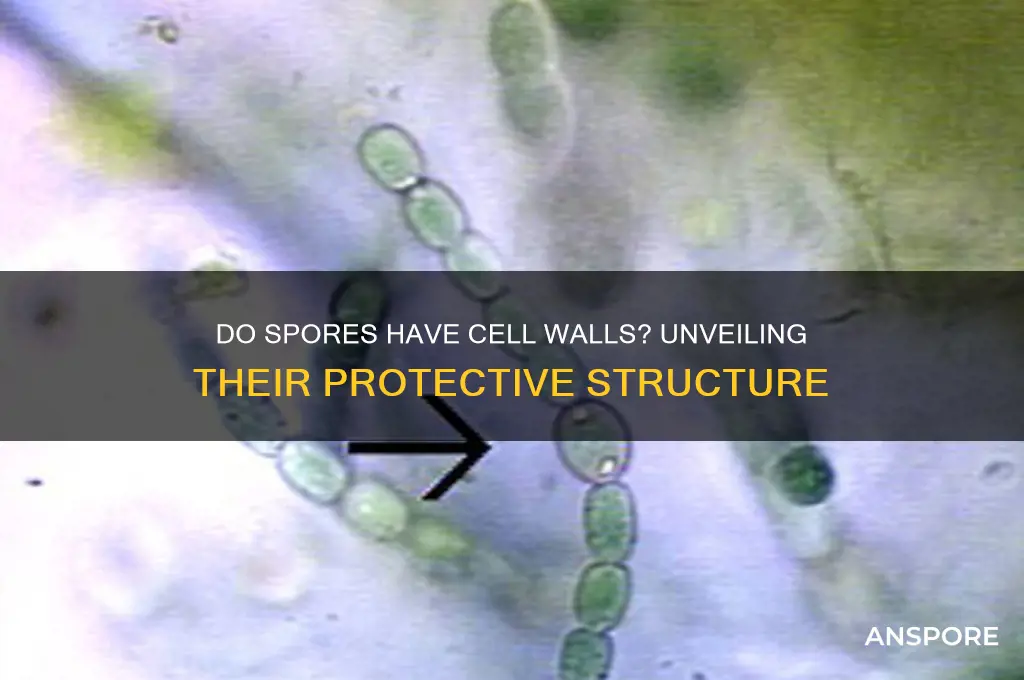

Spores, the resilient survival structures of certain organisms, possess cell walls that are distinctly thicker and more robust compared to those of vegetative cells. This increased thickness is a critical adaptation for withstanding harsh environmental conditions such as desiccation, extreme temperatures, and chemical stressors. For instance, bacterial endospores have cell walls composed of multiple layers, including a thick layer of peptidoglycan and additional protective proteins like dipicolinic acid, which contribute to their durability. In contrast, vegetative cells have thinner, more flexible cell walls optimized for growth and metabolic activity rather than long-term survival.

To understand the structural differences, consider the composition of spore cell walls. Fungal spores, for example, often contain chitin and other polysaccharides that enhance rigidity and resistance to degradation. This contrasts with the cell walls of vegetative fungal cells, which are primarily composed of glucan and chitin but in a less compact arrangement. The spore’s wall structure is designed to minimize water loss and resist enzymatic breakdown, making it a formidable barrier against external threats. Such architectural differences are not merely incidental but are evolutionary strategies to ensure spore longevity.

A practical example of this thickness and structural difference can be observed in *Bacillus subtilis* endospores. Their cell walls are up to 10 times thicker than those of vegetative cells, measuring around 40–60 nm compared to 5–10 nm. This thickness, combined with a modified peptidoglycan layer and additional protective coatings, allows spores to remain dormant for years or even centuries. For researchers or industries working with spores, understanding this structural disparity is crucial for applications like spore decontamination, where breaking through the spore’s thick wall requires specific treatments, such as high-temperature steam sterilization (autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes).

From a comparative perspective, the spore’s cell wall is not just thicker but also more chemically and physically resistant. While vegetative cells rely on their walls for shape and basic protection, spores use theirs as a fortress. For instance, fungal spores treated with common antifungal agents often survive due to their impermeable walls, whereas vegetative cells are more susceptible. This highlights the need for tailored approaches in fields like agriculture and medicine, where targeting spores versus vegetative cells requires different strategies.

In conclusion, the spore cell wall’s thickness and structure are specialized features that set them apart from vegetative cells. This distinction is not merely a biological curiosity but has practical implications for industries ranging from food preservation to pharmaceutical development. By recognizing these differences, scientists and practitioners can devise more effective methods for spore control, activation, or utilization, ensuring better outcomes in both research and applied settings.

Dyson Purifier vs. Mold Spores: Can It Effectively Combat Growth?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.25 $11.99

Cell Wall Formation: At what stage of spore development does the cell wall form?

Spores, the resilient survival structures of various organisms, undergo a complex developmental process, and the formation of their cell walls is a critical step in ensuring their durability. This process is not a singular event but a carefully orchestrated sequence integrated into the spore's maturation. The cell wall, a robust protective layer, begins to take shape during the spore maturation phase, a stage that follows the initial division of the sporocyte (the cell that gives rise to spores). This phase is marked by the deposition of specialized polymers, primarily chitin in fungi and peptidoglycan in bacteria, which provide structural integrity and protection against environmental stressors.

From an analytical perspective, the timing of cell wall formation is strategically aligned with the spore's need for survival. As the spore transitions from a metabolically active cell to a dormant, resilient structure, the cell wall acts as a barrier against desiccation, UV radiation, and enzymatic degradation. In fungi, for instance, the cell wall begins to thicken and harden during the late stages of sporulation, coinciding with the accumulation of storage compounds like lipids and proteins. This synchronization ensures that the spore is fully equipped to withstand harsh conditions before dispersal.

Instructively, understanding this developmental stage is crucial for applications in biotechnology and agriculture. For example, disrupting cell wall formation in fungal pathogens can render their spores non-viable, offering a targeted approach to disease control. Conversely, enhancing cell wall robustness in beneficial spores, such as those of mycorrhizal fungi, can improve their survival during storage and application. Practical tips include monitoring sporulation conditions (e.g., humidity, temperature) to optimize cell wall development, as suboptimal environments can lead to weak or incomplete walls.

Comparatively, the cell wall formation in bacterial spores (endospores) differs significantly from that in fungal spores. In bacteria, the cell wall is partially degraded during the early stages of sporulation, and a new, modified wall (the cortex) is synthesized around the developing spore. This process is followed by the assembly of an outer proteinaceous coat, which, while not a cell wall, serves a similar protective function. The distinct timing and composition of these structures highlight the evolutionary adaptations of different organisms to spore-mediated survival.

Descriptively, the cell wall formation stage is a visually striking phase under microscopy. In fungi, the spore's surface transforms from a smooth, uniform appearance to a textured, layered structure as polymers are deposited. In bacteria, the developing endospore can be seen as a bright, refractile body within the mother cell, with the cortex and coat layers becoming discernible as sporulation progresses. These visual cues are invaluable for researchers and practitioners in assessing spore viability and quality.

In conclusion, the cell wall formation during spore development is a precisely timed and functionally critical process. Whether in fungi or bacteria, this stage ensures that spores are equipped with the structural resilience needed for long-term survival. By understanding and manipulating this process, we can harness the potential of spores in various fields, from pest control to ecosystem restoration. Practical considerations, such as optimizing environmental conditions and monitoring developmental markers, are essential for leveraging this knowledge effectively.

Are Spore Servers Still Active? Exploring the Current Status

You may want to see also

Species Variations: Do all spore-producing organisms (e.g., fungi, bacteria) have cell walls in their spores?

Spores, the resilient survival structures of various organisms, exhibit remarkable diversity in their composition and function. Among the critical features to consider is the presence of cell walls, which provide structural integrity and protection. While it is widely known that fungal spores possess cell walls, the scenario becomes more nuanced when examining bacterial spores and other spore-producing organisms. This variation highlights the importance of understanding species-specific adaptations in spore biology.

Fungal spores, such as those produced by molds and mushrooms, are universally encased in cell walls composed primarily of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides. These cell walls are essential for withstanding environmental stresses, including desiccation and predation. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores have robust cell walls that enable them to persist in diverse habitats, from soil to indoor environments. This consistency in fungal spore structure underscores the evolutionary advantage of cell walls in ensuring spore longevity and dispersal.

In contrast, bacterial spores, exemplified by those of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, present a different scenario. While bacterial spores are renowned for their extreme resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals, their protective layers do not strictly qualify as cell walls. Instead, they are enveloped by a proteinaceous coat and an outer exosporium, which serve analogous functions to cell walls by providing durability and protection. This distinction is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of bacterial spore survival and for developing targeted sterilization methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes.

Beyond fungi and bacteria, other spore-producing organisms, like certain algae and plants, further complicate the picture. For example, fern spores possess cell walls composed of sporopollenin, a highly resistant polymer that enables them to endure harsh conditions. Similarly, pollen grains, though not spores in the strictest sense, have cell walls that facilitate their role in reproduction. These variations emphasize the need to approach spore biology with a species-specific lens, recognizing that structural adaptations are tailored to the organism’s ecological niche.

In practical terms, understanding these species variations is vital for fields such as microbiology, agriculture, and medicine. For instance, knowing that bacterial spores lack traditional cell walls informs the development of antimicrobial strategies, while the presence of sporopollenin in fern spores explains their fossilization potential, aiding paleobotanical research. By dissecting these differences, scientists and practitioners can harness spore biology more effectively, whether for preserving food, treating infections, or studying evolutionary history.

Effective Ways to Purify Air and Eliminate Mold Spores Safely

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores do have cell walls. These cell walls are typically composed of complex polymers like chitin in fungi or sporopollenin in plants, providing structural support and protection.

Yes, spore cell walls are often thicker and more resistant than those of vegetative cells. This adaptation helps spores survive harsh environmental conditions, such as drought, heat, or chemicals.

The primary function of a spore's cell wall is to protect the genetic material inside the spore from environmental stressors, ensuring long-term survival and dispersal.

No, the composition of spore cell walls varies depending on the organism. For example, fungal spores contain chitin, while plant spores (like pollen) have sporopollenin, and bacterial spores have a unique layer called the exosporium.