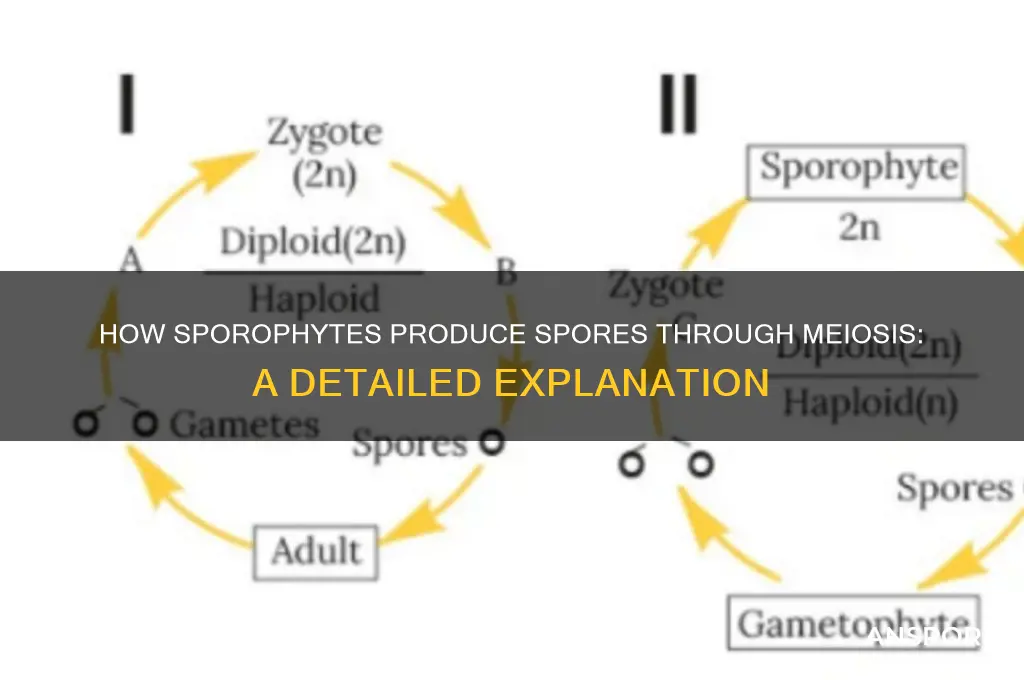

The sporophyte generation in plants is a crucial phase of their life cycle, particularly in vascular plants such as ferns, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. During this stage, the sporophyte produces spores through the process of meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid cells. This reduction division occurs in specialized structures called sporangia, where diploid sporocytes undergo meiosis to form four haploid spores. These spores are then dispersed and, under favorable conditions, germinate to develop into the gametophyte generation. Understanding this process is essential for comprehending the alternation of generations in plant life cycles and the mechanisms by which plants reproduce and adapt to their environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process of Spore Production | Sporophytes produce spores through meiosis. |

| Type of Spores Produced | Haploid spores (n chromosomes). |

| Genetic Variation | Meiosis introduces genetic diversity via crossing over and recombination. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Occurs in the diploid (2n) phase of the plant life cycle. |

| Resulting Structures | Spores develop into gametophytes (haploid phase). |

| Examples of Plants | Ferns, mosses, gymnosperms, and angiosperms. |

| Significance | Essential for alternation of generations in plant life cycles. |

| Location of Meiosis | Takes place in sporangia (structures on the sporophyte). |

| Energy Requirement | Requires energy for cell division and spore formation. |

| Environmental Factors | Influenced by light, temperature, and humidity. |

Explore related products

$13.29 $22.99

What You'll Learn

- Meiosis Process in Sporophytes: Sporophytes undergo meiosis to reduce chromosome number for spore formation

- Spore Types Produced: Meiosis results in haploid spores: spores, gametophytes, or next-generation plants

- Sporangia Role: Sporangia house sporocytes where meiosis occurs to produce spores

- Life Cycle Connection: Spores develop into gametophytes, completing the alternation of generations cycle

- Meiosis vs. Mitosis: Meiosis ensures genetic diversity in spores, unlike mitosis in vegetative growth

Meiosis Process in Sporophytes: Sporophytes undergo meiosis to reduce chromosome number for spore formation

Sporophytes, the diploid phase in the life cycles of plants, algae, and certain fungi, rely on meiosis to produce spores. This process is fundamental to their reproductive strategy, ensuring genetic diversity and the continuation of their life cycle. Meiosis, a specialized form of cell division, reduces the chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n), creating spores that can develop into the gametophyte generation. Without meiosis, sporophytes would be unable to transition to the next phase of their life cycle, disrupting their reproductive success.

The meiosis process in sporophytes begins with the replication of DNA in the diploid cells of the sporophyte’s reproductive organs, such as sporangia. This is followed by two rounds of cell division: meiosis I and meiosis II. During meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up, exchange genetic material through crossing over, and then separate, reducing the chromosome number by half. Meiosis II involves the division of sister chromatids, resulting in four haploid cells. These cells develop into spores, each carrying a unique genetic makeup due to the recombination events during meiosis. This genetic diversity is crucial for adaptation and survival in changing environments.

One practical example of this process is observed in ferns. The sporophyte generation of a fern produces sporangia on the undersides of its fronds. Within these sporangia, meiosis occurs, generating haploid spores. These spores are released and, upon landing in a suitable environment, germinate into gametophytes. The gametophytes then produce gametes, which fuse to form a new sporophyte, completing the cycle. This illustrates how meiosis in sporophytes is not just a biological mechanism but a key driver of their life cycle.

Understanding the meiosis process in sporophytes has significant implications for agriculture and conservation. For instance, in crop plants like wheat and maize, which have complex life cycles involving sporophyte and gametophyte stages, optimizing meiosis can enhance genetic diversity and improve crop resilience. Researchers can manipulate environmental conditions, such as temperature and nutrient availability, to influence meiosis efficiency. For example, maintaining a temperature range of 15–25°C during sporophyte development can promote healthy meiosis in many plant species. Additionally, ensuring adequate levels of micronutrients like zinc and boron, which are essential for DNA replication and cell division, can support the meiosis process.

In conclusion, the meiosis process in sporophytes is a finely tuned mechanism that ensures the reduction of chromosome number and the formation of genetically diverse spores. By studying and optimizing this process, scientists can enhance plant productivity and biodiversity. Whether in natural ecosystems or agricultural settings, the role of meiosis in sporophytes underscores its importance in sustaining life cycles and promoting genetic variation. Practical steps, such as monitoring environmental conditions and nutrient levels, can further support this critical biological process.

Do All Mushrooms Reproduce with Spores? Unveiling Fungal Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Spore Types Produced: Meiosis results in haploid spores: spores, gametophytes, or next-generation plants

Meiosis in sporophytes is a fundamental process that ensures genetic diversity and the continuation of plant life cycles. This specialized type of cell division reduces the chromosome number by half, producing haploid spores. These spores are not just byproducts of meiosis; they are the cornerstone of plant reproduction, serving as the foundation for gametophytes or developing directly into the next generation of plants. Understanding the types of spores produced and their roles provides insight into the intricate strategies plants employ to thrive across diverse environments.

Analytically, the spores generated through meiosis fall into distinct categories based on their function and developmental pathway. In vascular plants like ferns and seed plants, meiosis in the sporophyte phase produces two primary types of spores: microspores and megaspores. Microspores develop into male gametophytes, which typically produce sperm cells, while megaspores give rise to female gametophytes, responsible for egg production. This division of labor ensures efficient fertilization and highlights the precision of plant reproductive systems. Non-vascular plants, such as mosses, produce a single type of spore that grows into a bisexual gametophyte, capable of producing both male and female reproductive structures.

Instructively, observing these processes in a laboratory or educational setting can deepen understanding. For instance, to study spore development in ferns, collect mature sporangia from the undersides of fern leaves and examine them under a microscope. Apply a gentle heat source to release the spores, and note their size and distribution. For seed plants, dissect a flower to locate the anthers (microspores) and ovules (megaspores), observing their distinct structures. These hands-on activities illustrate how meiosis in sporophytes directly contributes to the diversity of spore types and their subsequent roles in plant reproduction.

Persuasively, the production of haploid spores through meiosis is a testament to the efficiency and adaptability of plant life cycles. By generating genetically unique spores, plants increase their resilience to environmental changes and diseases. For example, in agricultural settings, understanding spore diversity can inform breeding programs, leading to crop varieties better suited to specific climates or resistant to pests. Similarly, conservation efforts benefit from this knowledge, as it aids in the propagation of endangered plant species through spore cultivation and gametophyte development.

Comparatively, the spore types produced by meiosis in sporophytes differ significantly from those in fungi, which also utilize spores for reproduction. While plant spores are haploid and develop into gametophytes or new plants, fungal spores can be haploid, diploid, or dikaryotic, depending on the species and life cycle stage. This distinction underscores the unique evolutionary pathways of plants and fungi, despite their shared reliance on spores for survival and dispersal. Such comparisons highlight the diversity of reproductive strategies in the natural world and the importance of meiosis in driving this variation.

Descriptively, the journey of a spore from its formation in the sporophyte to its role in the next generation is a marvel of biological precision. Imagine a megaspore nestled within an ovule, its haploid nucleus carrying half the genetic material of its parent plant. As it germinates, it gives rise to a female gametophyte, a tiny, multicellular structure that will nurture the egg cell. Meanwhile, microspores released from anthers develop into pollen grains, each housing a male gametophyte. These spores, though microscopic, encapsulate the potential for new life, bridging generations and ensuring the continuity of plant species across time and space.

Can I Buy a Key Registration for Spor? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Sporangia Role: Sporangia house sporocytes where meiosis occurs to produce spores

Sporangia, the often-overlooked structures in plant and fungal life cycles, play a pivotal role in the production of spores. These specialized organs house sporocytes, the cells destined to undergo meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half. This process is fundamental to the alternation of generations in plants, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. Without sporangia, sporocytes would lack the protected environment necessary for meiosis, disrupting the entire reproductive cycle.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern, a classic example of a plant with distinct sporophyte and gametophyte generations. The sporophyte phase, the more visible and familiar fern plant, develops sporangia on the undersides of its leaves. Within these sporangia, sporocytes undergo meiosis, producing haploid spores. These spores are then dispersed, germinating into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes. This alternation between diploid sporophytes and haploid gametophytes is a direct result of the sporangia’s role in housing and facilitating meiosis.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporangia’s function is crucial for horticulture and agriculture. For instance, in cultivating mosses or ferns, gardeners must ensure conditions that support sporangia development, such as adequate humidity and light. Disrupting sporangia formation, whether through environmental stress or physical damage, can halt spore production, stunting the plant’s lifecycle. Similarly, in fungal cultivation, sporangia (or analogous structures like conidiophores) are essential for spore dispersal, making their health a priority for mycologists and farmers alike.

Comparatively, sporangia in fungi and plants share the common purpose of spore production but differ in structure and mechanism. In fungi, sporangia often develop at the tips of hyphae, releasing spores through rupture or active discharge. In contrast, plant sporangia are typically embedded in tissues, releasing spores through dehiscence. Despite these differences, the core function remains: sporangia provide a specialized environment for sporocytes to undergo meiosis, ensuring the continuation of the species.

In conclusion, sporangia are not merely passive containers but active participants in the reproductive process. By housing sporocytes and facilitating meiosis, they bridge the gap between generations, ensuring genetic diversity and survival. Whether in a fern frond or a fungal hypha, their role is indispensable, making them a fascinating and critical component of life cycles in plants and fungi. Understanding their function offers insights into both natural processes and practical applications, from gardening to biotechnology.

Multiplayer Mode in Spore: Can You Play with Friends?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Connection: Spores develop into gametophytes, completing the alternation of generations cycle

Sporophytes, the spore-producing phase in the life cycles of plants, algae, and fungi, indeed generate spores through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half. This process is critical for sexual reproduction and genetic diversity. The spores produced are not just miniature versions of the parent sporophyte; they are haploid cells destined to develop into gametophytes, the gamete-producing phase of the life cycle. This transition from sporophyte to gametophyte exemplifies the alternation of generations, a hallmark of many eukaryotic organisms.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a practical example. The visible fern plant is the sporophyte generation. On the underside of its fronds, it develops sporangia, structures where meiosis occurs, producing haploid spores. These spores are dispersed and, under suitable conditions, germinate into small, heart-shaped gametophytes (prothalli). The gametophyte generation is short-lived but crucial, as it produces gametes (sperm and eggs) that fuse to form a diploid zygote, which then grows into a new sporophyte. This cyclical process ensures genetic recombination and adaptability.

From an analytical perspective, the development of spores into gametophytes is a strategic evolutionary mechanism. By alternating between diploid and haploid phases, organisms maximize genetic diversity while maintaining stability. The sporophyte phase, being more robust and long-lived, can invest energy in growth and spore production, while the gametophyte phase focuses on sexual reproduction. This division of labor optimizes resource allocation and increases the species' chances of survival in varying environments.

For those studying or teaching this concept, a hands-on activity can deepen understanding. Collect fern spores from mature plants and sow them on a moist, soil-covered tray. Observe the development of prothalli under a magnifying glass, noting their structure and eventual production of gametes. This experiment not only illustrates the alternation of generations but also highlights the environmental conditions required for each phase, such as moisture for gametophyte survival.

In conclusion, the connection between spores developing into gametophytes and the completion of the alternation of generations cycle is a testament to the elegance of biological systems. It underscores the importance of meiosis in sporophytes, not just as a means of spore production, but as a foundational step in a complex life cycle. Understanding this process provides insights into the evolutionary strategies of plants and other organisms, offering both scientific and practical value.

Can You See Fungal Spores? Unveiling the Invisible World of Fungi

You may want to see also

Meiosis vs. Mitosis: Meiosis ensures genetic diversity in spores, unlike mitosis in vegetative growth

Sporophytes, the diploid phase in the life cycles of plants, ferns, and some algae, produce spores through meiosis, a process fundamentally distinct from mitosis. Meiosis is a specialized cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, creating haploid spores genetically unique from the parent. This reduction division is crucial for sexual reproduction and genetic diversity, ensuring that each spore carries a novel combination of traits. In contrast, mitosis maintains the chromosome number, producing genetically identical cells essential for vegetative growth and tissue repair. Understanding this difference highlights why meiosis is pivotal for evolutionary adaptability, while mitosis supports stable, asexual expansion.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a practical example. The sporophyte generation produces spores via meiosis in structures called sporangia. These spores, upon germination, grow into gametophytes, which are haploid and produce gametes. When fertilization occurs, a new sporophyte arises, completing the cycle. Meiosis here ensures that each spore is genetically distinct, increasing the species’ resilience to environmental changes. Mitosis, however, dominates the gametophyte phase, allowing for the rapid, clonal growth of this short-lived stage. This division of labor between meiosis and mitosis underscores their complementary roles in survival and propagation.

From an analytical perspective, meiosis introduces genetic diversity through two key mechanisms: crossing over during prophase I and random chromosome assortment. Crossing over swaps genetic material between homologous chromosomes, creating new allele combinations. Random assortment during metaphase I further shuffles these combinations, ensuring that each spore is genetically unique. Mitosis, lacking these mechanisms, produces exact replicas of the parent cell, ideal for maintaining tissue integrity but devoid of innovation. This contrast explains why meiosis is reserved for reproductive structures like spores, while mitosis drives the growth of roots, stems, and leaves.

To illustrate the practical implications, imagine a crop species facing a new disease. If the sporophyte relied solely on mitosis for spore production, all spores would be genetically identical, making the population uniformly susceptible. Meiosis, however, generates diverse spores, increasing the likelihood that some will possess resistance traits. Farmers can then select and cultivate these resistant individuals, safeguarding yields. This scenario underscores the evolutionary advantage of meiosis in spores, a principle applicable across agriculture, conservation, and biotechnology.

In conclusion, the distinction between meiosis and mitosis in sporophytes is not merely academic but a cornerstone of biological strategy. Meiosis ensures that spores are genetically diverse, equipping species to adapt and evolve, while mitosis supports the stable, asexual growth necessary for resource accumulation. By producing spores through meiosis, sporophytes balance innovation with stability, a duality essential for long-term survival. Recognizing this interplay offers insights into plant breeding, ecosystem resilience, and the fundamental mechanisms driving life’s complexity.

Do All Cells Produce Spores? Unraveling the Truth Behind Cellular Reproduction

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the sporophyte produces spores through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, resulting in haploid spores.

The sporophyte produces haploid spores through meiosis, which can develop into the gametophyte generation in the plant life cycle.

Meiosis is necessary for sporophyte spore production because it ensures genetic diversity and maintains the alternation of generations by producing haploid spores from the diploid sporophyte.