Daisies, beloved for their simple beauty and widespread presence, are often associated with seeds rather than spores. Unlike ferns, fungi, or certain non-flowering plants, daaisies reproduce primarily through seeds produced in their characteristic flower heads. Spores, which are microscopic reproductive units, are typically found in plants that do not produce flowers or seeds, such as mosses and ferns. Therefore, when considering whether a daisy has spores, the answer is no—daisies rely on seeds for reproduction, making them a prime example of flowering plants that utilize this method to propagate and thrive in diverse environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Method | Daisies reproduce sexually through seeds, not spores. |

| Seed Structure | Seeds are enclosed in achenes (small, dry fruits) with a pappus (hairy structure) for wind dispersal. |

| Spores Presence | Daisies do not produce spores; they are angiosperms (flowering plants). |

| Life Cycle | Follows a typical angiosperm life cycle: seed germination, vegetative growth, flowering, pollination, seed production. |

| Pollination | Primarily pollinated by insects (entomophily). |

| Classification | Belong to the family Asteraceae, which includes flowering plants, not spore-producing plants like ferns or fungi. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Seeds are dispersed by wind (via pappus) and occasionally by animals. |

| Spores in Related Plants | Spores are found in non-flowering plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, not in daisies or other angiosperms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Daisy Reproduction Methods: Daisies reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns or fungi

- Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are single-celled; daisy seeds are multicellular, containing embryos

- Daisy Life Cycle: Daisies grow from seeds, not spores, completing a flowering plant cycle

- Plants with Spores: Ferns, mosses, and fungi use spores; daisies do not

- Daisy Pollination Process: Daisies rely on pollinators and seeds, not spore dispersal mechanisms

Daisy Reproduction Methods: Daisies reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns or fungi

Daisies, those cheerful blooms dotting lawns and meadows, rely on seeds for reproduction, not spores. This fundamental distinction sets them apart from spore-dependent organisms like ferns and fungi. While spores are microscopic, single-celled structures capable of developing into new individuals without fertilization, daisy seeds are the product of sexual reproduction, containing a miniature plant embryo encased in a protective coat. This seed-based strategy allows daisies to disperse their offspring over greater distances, often aided by wind, animals, or human activity, ensuring the species' survival and proliferation.

Understanding the reproductive mechanism of daisies is crucial for gardeners and botanists alike. To encourage daisy growth, one must focus on seed collection and sowing rather than spore cultivation. Collect seeds from mature daisy heads, allowing them to dry thoroughly before storage. Sow seeds in well-draining soil during the cooler months of spring or fall, ensuring they are lightly covered but not buried too deeply. Maintain consistent moisture, and seedlings should emerge within 14 to 21 days. This method mimics the natural dispersal process, fostering healthy daisy populations in gardens or wildflower meadows.

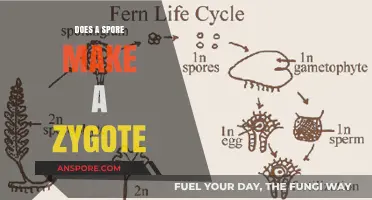

In contrast to ferns, which release spores that develop into gametophytes for sexual reproduction, daisies bypass this intermediate stage. Similarly, fungi rely on spores for asexual reproduction, spreading rapidly under favorable conditions. Daisies, however, invest energy in producing seeds, a more complex but reliable method for genetic diversity and long-term survival. This seed-based approach also makes daisies more adaptable to varying environmental conditions, as seeds can remain dormant until conditions are optimal for germination.

For those interested in propagating daisies, it’s essential to avoid common pitfalls. Overwatering can lead to seed rot, while insufficient light can hinder growth. Ensure seeds receive at least 6 hours of sunlight daily and keep the soil consistently moist but not waterlogged. Additionally, consider companion planting with species that attract pollinators, as daisies benefit from insect activity for seed production. By focusing on seed-specific care, enthusiasts can successfully cultivate daisies while appreciating their unique reproductive strategy.

In summary, daisies’ reliance on seeds for reproduction distinguishes them from spore-dependent organisms like ferns and fungi. This method ensures genetic diversity, adaptability, and efficient dispersal. By understanding and supporting seed-based reproduction, gardeners and botanists can foster thriving daisy populations, contributing to both ecological balance and aesthetic beauty. Whether in a garden or the wild, daisies exemplify the elegance of seed-driven life cycles, offering a practical and rewarding subject for study and cultivation.

How to Obtain Spore Prints from Portobello Mushrooms: A Guide

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are single-celled; daisy seeds are multicellular, containing embryos

Daisies, like all flowering plants, reproduce through seeds, not spores. This fundamental distinction hinges on cellular complexity. Spores are single-celled structures, often produced by plants like ferns and fungi, capable of developing into new organisms without fertilization. In contrast, daisy seeds are multicellular, housing an embryo—a miniature, undeveloped plant—alongside stored nutrients and a protective coat. This embryo, already formed through sexual reproduction, ensures genetic diversity and a head start for the next generation.

Consider the lifecycle: a spore must first germinate into a gametophyte, which then produces gametes for fertilization. Daisy seeds bypass this step. Each seed contains a pre-formed embryo, ready to sprout roots, shoots, and leaves upon germination. This efficiency reflects the evolutionary advantage of angiosperms (flowering plants) over spore-producing species, particularly in diverse and competitive environments.

For gardeners, understanding this difference is practical. Daisy seeds require specific conditions—moisture, warmth, and light—to activate growth. Spores, being simpler, often thrive in more varied environments. When sowing daisy seeds, ensure the soil is well-drained and lightly covered, as the embryo within is already equipped to grow, given the right conditions. Spores, however, might need a humid, shaded environment to initiate development.

From an ecological perspective, the multicellular nature of daisy seeds contributes to their success. The embryo’s stored energy allows the seedling to establish itself quickly, reducing vulnerability to predators and environmental stress. Spores, while resilient, rely on rapid division and external resources to survive. This comparison highlights why daisies dominate meadows and gardens, while spore-producing plants often occupy niche habitats.

In summary, while spores and seeds both serve reproductive purposes, their structures and lifecycles differ dramatically. Daisy seeds, with their multicellular embryos, exemplify the sophistication of flowering plants, offering a direct path to growth. Spores, though simpler, showcase the adaptability of earlier plant forms. Knowing this distinction not only enriches botanical knowledge but also informs practical gardening and conservation efforts.

Psilocybe Cubensis Spores in Texas: Legal Status Explained

You may want to see also

Daisy Life Cycle: Daisies grow from seeds, not spores, completing a flowering plant cycle

Daisies, those cheerful blooms dotting lawns and meadows, do not rely on spores for reproduction. Unlike ferns or mushrooms, which disperse tiny spores to propagate, daisies follow the classic flowering plant life cycle. This cycle begins with a seed, a compact package containing all the genetic material needed for a new plant. Understanding this distinction is crucial for gardeners and botanists alike, as it dictates how daisies are cultivated and cared for.

The life cycle of a daisy starts with germination, where the seed absorbs water and nutrients, triggering the emergence of a tiny root and shoot. This delicate seedling grows into a mature plant, developing leaves, stems, and eventually, the iconic flower heads. Each flower head is a composite structure, composed of many small florets. These florets produce pollen and ovules, which, after pollination, develop into seeds. This process highlights the daisy’s reliance on seeds as its primary means of reproduction, contrasting sharply with spore-producing plants.

For gardeners, knowing that daisies grow from seeds offers practical advantages. Seeds can be sown directly into the soil in spring or fall, depending on the species and climate. For example, Shasta daisies (Leucanthemum × superbum) thrive when planted in early spring, while English daisies (Bellis perennis) can be sown in fall for winter blooms. Proper spacing—about 12 to 18 inches apart—ensures adequate airflow and reduces competition for resources. Watering consistently but avoiding over-saturation prevents seed rot and promotes healthy growth.

Comparatively, spore-producing plants like ferns require specific conditions, such as high humidity and shade, to thrive. Daisies, however, are more adaptable, tolerating a range of soil types and sunlight levels. This adaptability makes them a favorite for both novice and experienced gardeners. By focusing on seed care—keeping the soil moist during germination and thinning seedlings to prevent overcrowding—gardeners can ensure a vibrant display of daisies year after year.

In conclusion, the daisy’s life cycle is a testament to the diversity of plant reproduction strategies. By growing from seeds rather than spores, daisies follow a predictable and manageable flowering plant cycle. This knowledge empowers gardeners to cultivate these charming blooms effectively, enhancing landscapes with their simple yet striking beauty. Whether in a formal garden or a wildflower meadow, daisies remind us of the elegance of nature’s design.

Copying Creations in Spore: Tips and Tricks for Duplicating Pieces

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Plants with Spores: Ferns, mosses, and fungi use spores; daisies do not

Daisies, with their bright petals and cheerful demeanor, reproduce through seeds, not spores. This fundamental difference sets them apart from plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, which rely on spores for propagation. Understanding this distinction is crucial for gardeners, botanists, and anyone curious about plant reproduction.

The Sporic World of Ferns, Mosses, and Fungi

Ferns, mosses, and fungi are part of a group of organisms that reproduce via spores, microscopic units designed for dispersal and survival in diverse environments. Ferns release spores from the undersides of their fronds, which develop into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes. Mosses follow a similar process, with spores growing into thread-like protonema before maturing into the recognizable moss plant. Fungi, including mushrooms and molds, produce spores in vast quantities, often released into the air or water to colonize new areas. These spores are lightweight and resilient, allowing them to travel far and wide, even in harsh conditions.

Daisies: A Seed-Based Strategy

In contrast, daisies employ seeds as their primary means of reproduction. Each daisy flower head is a composite of many small florets, which mature into seeds equipped with feathery bristles or other structures for wind dispersal. This seed-based approach is characteristic of angiosperms, or flowering plants, which dominate terrestrial ecosystems. Seeds contain a developing embryo, stored nutrients, and protective layers, giving them a survival advantage over spores in many environments. For gardeners, this means daisies can be easily propagated by collecting and sowing seeds, a straightforward process compared to the more delicate handling required for spore-based plants.

Practical Implications for Plant Care

If you’re cultivating ferns, mosses, or fungi, understanding their spore-based life cycle is essential. For example, ferns thrive in humid, shaded environments, and their spores require specific conditions to germinate, such as a sterile medium and consistent moisture. Mosses can be grown from spores by scattering them on damp soil and keeping the area misted. Fungi, like oyster mushrooms, are often cultivated using spore-infused substrates, such as sawdust or straw. Daisies, however, are low-maintenance and can be grown from seeds sown directly into well-drained soil, with full sun exposure for optimal flowering.

Why It Matters

The distinction between spore- and seed-based reproduction highlights the diversity of plant strategies for survival and propagation. Spores are ideal for colonizing new habitats quickly, while seeds provide a more robust mechanism for long-term growth and adaptation. For enthusiasts, recognizing these differences allows for more effective cultivation and appreciation of each plant’s unique biology. Whether you’re nurturing a fern in a terrarium or planting daisies in a garden bed, understanding their reproductive methods ensures healthier, more vibrant plants.

Do Actinobacteria Produce Spores? Unveiling Their Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Daisy Pollination Process: Daisies rely on pollinators and seeds, not spore dispersal mechanisms

Daisies, with their vibrant petals and cheerful demeanor, are a staple in gardens and meadows worldwide. Unlike ferns or fungi, which reproduce via spores, daisies rely on a sophisticated pollination process and seed dispersal to propagate. This distinction is crucial for understanding their life cycle and ecological role. Pollinators such as bees, butterflies, and even birds are drawn to daisies’ bright colors and nectar-rich centers, facilitating the transfer of pollen between flowers. Once pollinated, daisies produce seeds that are dispersed by wind, animals, or water, ensuring the next generation’s survival.

Consider the anatomy of a daisy to grasp its pollination mechanics. The flower head, or capitulum, consists of two types of florets: ray florets (the outer petals) and disk florets (the central cluster). Disk florets are the primary site of pollen production and seed development. When a pollinator lands on the flower, it brushes against the anthers, collecting pollen grains. As it moves to another daisy, these grains are deposited on the stigma, enabling fertilization. This process is highly efficient, maximizing the chances of successful seed production without relying on spores.

From a practical standpoint, gardeners can enhance daisy pollination by creating a pollinator-friendly environment. Planting daisies in clusters rather than singly increases their visibility to pollinators. Incorporating companion plants like lavender, coneflowers, or yarrow can also attract a diverse range of pollinators. Avoid using pesticides, as they harm beneficial insects. For seed collection, wait until the flower head turns brown and dry, then gently shake the seeds into a paper bag for storage. These seeds can be sown in spring or fall, depending on your climate, ensuring a continuous display of daisies year after year.

Comparatively, spore-based reproduction, as seen in ferns or mushrooms, is a simpler, more primitive mechanism. Spores are lightweight and can travel vast distances via wind, but they require specific conditions to germinate. Daisies, on the other hand, invest energy in producing seeds, which are more resilient and adaptable. This evolutionary strategy reflects daisies’ reliance on pollinators and their ability to thrive in diverse environments. While spores are efficient for certain organisms, daisies’ pollination-seed system is a testament to their ecological success and adaptability.

In conclusion, daisies’ pollination process underscores their dependence on external agents and seeds for reproduction, setting them apart from spore-dispersing organisms. By understanding this mechanism, gardeners and enthusiasts can better support daisy populations and appreciate their role in ecosystems. Whether you’re cultivating a garden or simply admiring these flowers in the wild, recognizing their unique reproductive strategy adds depth to their beauty and significance.

Peace Lilies and Mold: Do They Absorb Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, daisies do not have spores. They are flowering plants that reproduce through seeds.

Daisies reproduce through pollination, where pollen from the male part (anther) is transferred to the female part (stigma), leading to seed production.

No, spores are not part of a daisy’s life cycle. Spores are typically associated with non-flowering plants like ferns and fungi, not flowering plants like daisies.

Daisies produce seeds, not spores. Seeds are the result of sexual reproduction in flowering plants, while spores are asexual reproductive units found in other types of organisms.