The question of whether a eukaryote spore has a seed coat is rooted in the distinction between plant reproductive structures and the protective mechanisms of different organisms. Eukaryotic spores, commonly found in fungi, algae, and some plants, are typically unicellular or multicellular structures designed for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. Unlike seeds, which are characteristic of angiosperms and gymnosperms and are encased in a protective seed coat (testa), spores generally lack such a specialized outer layer. Instead, spores rely on their resilient cell walls, often composed of materials like chitin or sporopollenin, to withstand environmental stresses. While both seeds and spores serve reproductive purposes, their structural adaptations reflect their evolutionary divergence and the specific challenges they face in their respective environments.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Presence of Seed Coat | Eukaryote spores do not have a seed coat. Seed coats are exclusive to seeds of seed-bearing plants (spermatophytes), which are a subset of eukaryotes. Spores, produced by plants like ferns, fungi, and some algae, lack this structure. |

| Structure | Spores are typically single-celled or multicellular reproductive units with a protective wall, but not a seed coat. They are often lightweight and adapted for dispersal. |

| Function | Spores are primarily for asexual or sexual reproduction and dispersal, while seeds contain an embryo and stored nutrients, protected by a seed coat. |

| Organisms Producing Spores | Fungi, non-seed plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and some algae produce spores. Seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms) produce seeds instead. |

| Protection Mechanism | Spores have a resistant outer wall but lack the complex protective layers of a seed coat. They rely on dormancy and environmental triggers for germination. |

| Nutrient Storage | Spores generally do not store nutrients, unlike seeds, which contain endosperm or cotyledons for the developing embryo. |

Explore related products

$29.99

$18.98

$19.98

What You'll Learn

- Spore vs. Seed Structure: Comparing the protective layers of eukaryotic spores and seeds

- Seed Coat Function: Role of seed coats in protection and dormancy

- Spore Wall Composition: Materials forming the outer layer of eukaryotic spores

- Germination Differences: How spores and seeds initiate growth without a seed coat

- Eukaryotic Spore Protection: Mechanisms spores use instead of a seed coat for survival

Spore vs. Seed Structure: Comparing the protective layers of eukaryotic spores and seeds

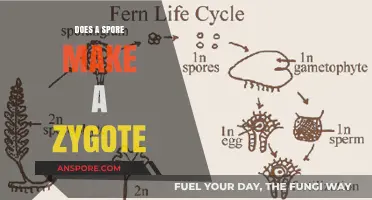

Eukaryotic spores and seeds both serve as dispersal units for plants and fungi, but their protective layers differ significantly in structure and function. While seeds are characteristic of plants (embryophytes), spores are produced by a variety of eukaryotic organisms, including fungi, ferns, and mosses. A seed’s protective layer, known as the seed coat (testa), is a hardened, multi-layered structure derived from the ovule’s integuments. In contrast, spores lack a seed coat; instead, they are often encased in a thin, resilient wall composed of sporopollenin, a highly durable biopolymer. This fundamental difference highlights the distinct evolutionary adaptations of spores and seeds to their respective environments and dispersal mechanisms.

To understand the protective layers of spores, consider the example of fern spores. These microscopic units are surrounded by a single-layered wall that provides resistance to desiccation, UV radiation, and mechanical stress. The sporopollenin in this wall is remarkably inert, allowing spores to remain viable for extended periods in harsh conditions. In contrast, a seed coat is more complex, often consisting of multiple layers (e.g., outer testa and inner tegmen) that protect the embryo, store nutrients, and regulate water uptake during germination. For instance, the seed coat of a bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) is thick and impermeable, preventing premature germination until conditions are favorable. This comparison underscores how spores prioritize durability and dispersal, while seeds emphasize protection and resource allocation.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these structural differences is crucial for horticulture, agriculture, and conservation. Gardeners working with spore-bearing plants like ferns must ensure proper humidity and light conditions to encourage spore germination, as their protective layers offer limited nutrient storage. Conversely, seed-sowing techniques often involve scarification or stratification to breach the seed coat’s defenses, simulating natural processes that trigger germination. For example, cold stratification for 4–6 weeks at 1–5°C is recommended for seeds with hard coats, such as those of certain perennials, to enhance water uptake and initiate growth. These methods highlight the need to tailor approaches based on the unique protective mechanisms of spores and seeds.

A persuasive argument can be made for the superiority of seeds in terms of evolutionary success. The seed coat’s complexity allows plants to colonize diverse habitats by protecting the embryo and storing resources, contributing to the dominance of seed plants (spermatophytes) in terrestrial ecosystems. Spores, while highly efficient for dispersal, rely on external conditions for germination and lack the internal resources of seeds. However, this does not diminish the ecological importance of spore-bearing organisms; fungi, for instance, play critical roles in nutrient cycling and symbiotic relationships. Ultimately, the protective layers of spores and seeds reflect distinct strategies for survival and propagation, each tailored to the organism’s life cycle and environmental niche.

In conclusion, the protective layers of eukaryotic spores and seeds reveal contrasting adaptations to their roles in dispersal and germination. While spores rely on a thin, durable wall for resilience, seeds employ a complex coat for protection and resource management. Recognizing these differences enables informed practices in horticulture, conservation, and research, ensuring the successful propagation of both spore-bearing and seed-bearing organisms. Whether cultivating ferns or growing crops, understanding these structures is key to harnessing the unique biology of each reproductive unit.

Can Frankia Form Spores? Unveiling the Truth About This Unique Bacterium

You may want to see also

Seed Coat Function: Role of seed coats in protection and dormancy

Eukaryotic spores, such as those produced by fungi and some plants, lack a seed coat, a structure exclusive to seeds of seed-bearing plants (spermatophytes). However, the protective and dormancy-inducing functions of seed coats offer valuable insights into the adaptive strategies of reproductive structures across eukaryotes. Seed coats, composed of maternally derived tissues, serve as a critical interface between the embryo and the environment, balancing protection with the eventual need for germination.

Mechanisms of Protection

Seed coats act as a physical barrier against mechanical damage, pathogens, and herbivores. Composed of layers like the testa and tegmen, they are often hardened with lignin, suberin, or tannins, which deter pests and resist decay. For example, the seed coat of the lotus (*Nelumbo nucifera*) contains impermeable layers that prevent water uptake, protecting the embryo in aquatic environments. Similarly, the thick, woody coat of the coconut (*Cocos nucifera*) safeguards the seed during long-distance dispersal across oceans. These adaptations highlight the seed coat’s role in ensuring survival in diverse and often hostile conditions.

Regulation of Dormancy

Beyond protection, seed coats play a pivotal role in enforcing dormancy, a state of suspended growth that ensures germination occurs under optimal conditions. This is achieved through mechanical or chemical inhibition. In mechanical dormancy, the hard seed coat restricts embryo expansion, as seen in legumes like *Lupinus*. Chemical dormancy, on the other hand, involves compounds within the coat that inhibit germination until specific environmental cues, such as scarification or stratification, are met. For instance, the seed coat of *Beta vulgaris* (beet) contains inhibitors that are neutralized by exposure to light, triggering germination. This dual function of protection and dormancy regulation underscores the seed coat’s complexity as a multifunctional structure.

Practical Implications and Applications

Understanding seed coat function has practical applications in agriculture and conservation. Farmers use scarification techniques, such as sanding or hot-water treatment, to weaken hard seed coats and improve germination rates in crops like *Phaseolus vulgaris* (common bean). In seed banking, the durability of seed coats is leveraged to preserve genetic diversity, as seen in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, where seeds with robust coats are stored for decades without deterioration. Additionally, studying seed coat chemistry can inspire the development of biodegradable materials or natural pest deterrents, bridging ecological insights with technological innovation.

Comparative Perspective with Eukaryotic Spores

While eukaryotic spores lack a seed coat, they employ alternative strategies to achieve similar protective and dormancy functions. Fungal spores, for instance, have cell walls fortified with chitin, providing resistance to environmental stresses. Plant spores, like those of ferns, rely on lightweight, resilient walls for dispersal and survival. Though structurally distinct, these adaptations reflect convergent evolutionary solutions to the challenges of protection and dormancy. By contrasting seed coats with spore structures, we gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity of reproductive strategies in eukaryotes and the principles that govern their survival.

Do We Swallow Mold Spores? Unveiling the Hidden Truth

You may want to see also

Spore Wall Composition: Materials forming the outer layer of eukaryotic spores

Eukaryotic spores, unlike seeds, do not possess a seed coat. Instead, they are encased in a specialized structure known as the spore wall, which serves as a protective barrier against environmental stresses. This wall is composed of a diverse array of materials, each contributing to the spore's durability, resistance, and ability to remain dormant for extended periods. Understanding the composition of the spore wall is crucial for fields such as microbiology, agriculture, and biotechnology, as it influences spore survival and dispersal mechanisms.

The primary components of the spore wall include sporopollenin, a highly resistant biopolymer found in plant spores, and chitin or chitosan in fungal spores. Sporopollenin, for instance, is renowned for its chemical inertness and mechanical strength, enabling spores to withstand extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, and UV radiation. In fungi, chitin provides structural integrity and acts as a barrier against microbial invasion. Additionally, spore walls often contain proteins and lipids, which play roles in germination regulation and protection against oxidative stress. For example, in *Bacillus* endospores, a layer of dipicolinic acid and calcium ions is embedded within the spore coat, contributing to heat resistance and DNA stabilization.

Analyzing the spore wall composition reveals its adaptive significance. For instance, the thick, multilayered walls of fungal spores allow them to persist in soil for decades, while the lightweight yet robust walls of fern spores facilitate wind dispersal. In contrast, bacterial endospores, with their keratin-like outer layers, can survive in harsh environments, including outer space. This diversity in composition highlights the evolutionary tailoring of spore walls to specific ecological niches, ensuring species survival across varying conditions.

Practical applications of spore wall research are vast. In agriculture, understanding sporopollenin could lead to the development of drought-resistant crops. In medicine, manipulating spore wall proteins might enhance vaccine delivery systems, as spores can act as stable carriers for antigens. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores have been engineered to display foreign proteins on their surface, serving as oral vaccines. However, caution is necessary when altering spore wall composition, as changes may inadvertently affect germination efficiency or environmental resilience.

To study spore wall composition, techniques such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) are employed. These methods allow researchers to identify and quantify wall components, providing insights into their structural and functional roles. For DIY enthusiasts, simple staining techniques using calcofluor white (for chitin) or Sudan black (for lipids) can reveal spore wall layers under a fluorescence microscope. Such explorations not only deepen scientific understanding but also inspire innovations in biomimicry and material science.

Are Fungal Spores Airborne? Unveiling the Truth About Their Spread

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Differences: How spores and seeds initiate growth without a seed coat

Spores and seeds, though both agents of plant reproduction, diverge sharply in their germination mechanisms, particularly when considering the absence of a seed coat. Unlike seeds, which often rely on a protective seed coat to regulate germination, spores initiate growth through a more direct interaction with their environment. This distinction is critical in understanding how these reproductive units respond to external stimuli. For instance, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus niger*, germinate upon contact with moisture and suitable nutrients, bypassing the need for a seed coat entirely. This process is rapid, often occurring within hours under optimal conditions, and is driven by the spore’s thin, permeable cell wall, which allows immediate nutrient uptake.

In contrast, seeds without a seed coat, such as those of some gymnosperms or artificially decoated angiosperms, face unique challenges in initiating growth. The absence of a seed coat exposes the embryo to environmental stressors, requiring internal mechanisms to compensate. For example, naked seeds of pine trees (*Pinus* spp.) rely on thick, resinous coatings and chemical inhibitors within the embryo itself to prevent premature germination. When conditions are favorable, these inhibitors degrade, allowing the embryo to mobilize stored resources and begin growth. This internal regulation contrasts with the external responsiveness of spores, highlighting the evolutionary adaptations of each reproductive strategy.

To facilitate germination in seed coat-deficient seeds, horticulturists employ specific techniques. For instance, scarification—mechanically or chemically weakening the seed’s outer layer—can mimic the protective function of a seed coat. Similarly, stratification, a process of exposing seeds to alternating temperatures and moisture levels, helps break dormancy in species like *Acer saccharum* (sugar maple). These methods underscore the importance of replicating the seed coat’s role in regulating water uptake and enzyme activation, which are critical for successful germination.

Spores, however, thrive on simplicity. Their germination is often triggered by minimal cues, such as a 20–30% increase in humidity or the presence of specific sugars in the environment. For example, *Penicillium* spores germinate efficiently at relative humidities above 85%, with optimal growth occurring at temperatures between 20–30°C. This minimal requirement for external protection allows spores to colonize diverse habitats rapidly, from soil to decaying matter. Their resilience lies in their ability to remain dormant for extended periods, germinating only when conditions are precisely aligned.

In practical terms, understanding these germination differences is essential for agriculture, conservation, and biotechnology. For seed coat-deficient seeds, controlled environments with precise humidity (60–70%) and temperature (22–25°C) can enhance germination rates. Spores, on the other hand, are harnessed in industrial processes like fermentation, where their rapid germination is optimized by adjusting nutrient concentrations and pH levels. By leveraging these unique mechanisms, scientists and practitioners can maximize the potential of both spores and seeds, even in the absence of a seed coat.

Did EA Ruin Spore? Exploring the Game's Unfulfilled Potential

You may want to see also

Eukaryotic Spore Protection: Mechanisms spores use instead of a seed coat for survival

Eukaryotic spores, unlike seeds, lack a seed coat, yet they thrive in diverse and often harsh environments. This survival is attributed to a suite of protective mechanisms that compensate for the absence of a rigid outer layer. One such mechanism is the spore wall, a robust, multilayered structure composed of complex polymers like chitin, glucans, and proteins. In fungi, for example, the spore wall provides mechanical strength, resisting desiccation and chemical damage. Similarly, in ferns and other spore-producing plants, the exine layer of the spore wall acts as a barrier against UV radiation and microbial invasion. These walls are not static; they can adapt to environmental stressors, thickening or altering composition to enhance resilience.

Another critical survival strategy is dormancy, a state of metabolic inactivity that allows spores to endure unfavorable conditions for extended periods. This mechanism is particularly evident in bacterial endospores, which can remain viable for centuries. Dormancy is regulated by internal signals and environmental cues, such as nutrient scarcity or temperature extremes. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores enter dormancy when starved, reactivating only when conditions improve. This metabolic pause minimizes energy expenditure and shields the spore’s genetic material from damage, ensuring long-term survival without the need for a seed coat.

Spores also employ chemical defenses to ward off predators and pathogens. Many fungal spores produce secondary metabolites, such as toxins or antifungal compounds, that deter consumption or infection. For example, *Aspergillus* spores release gliotoxin, a potent antimicrobial agent. Similarly, plant spores often contain phenolic compounds that inhibit microbial growth. These chemical defenses act as an invisible shield, compensating for the physical vulnerability of lacking a seed coat.

A less obvious but equally vital mechanism is dispersal efficiency. Spores are typically lightweight and aerodynamic, allowing them to travel vast distances via wind or water. This dispersal minimizes competition and increases the likelihood of finding suitable habitats. For instance, fern spores are so small and lightweight that they can remain airborne for days, colonizing distant environments. This strategy reduces the need for a protective seed coat by ensuring spores reach environments where they can germinate and thrive.

Finally, spores leverage environmental triggers to time their germination optimally. Unlike seeds, which rely on a seed coat to regulate germination, spores respond directly to external cues such as moisture, temperature, and light. For example, moss spores germinate only in the presence of water and specific light conditions, ensuring they activate in environments conducive to growth. This precision in timing reduces the risk of premature germination and enhances survival rates, even without a seed coat.

In summary, eukaryotic spores employ a combination of physical, chemical, and behavioral mechanisms to survive without a seed coat. From resilient spore walls and dormancy to chemical defenses and strategic dispersal, these adaptations ensure spores can endure and thrive in diverse environments. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on spore biology but also inspires biomimetic solutions for preserving and protecting fragile biological materials.

Comparing Selaginella Spore Sizes: Are They Uniform Across Species?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, eukaryote spores do not have a seed coat. Spores are reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some protists, and they lack the protective seed coat found in seeds of seed-bearing plants (spermatophytes).

Eukaryote spores are protected by a tough outer wall made of materials like chitin (in fungi) or sporopollenin (in plants). This wall provides resistance to harsh environmental conditions, such as desiccation and radiation.

No, eukaryote spores and seeds are different. Spores are haploid, single-celled structures used for dispersal and survival, while seeds are diploid, multicellular structures that contain an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat. Seeds are exclusive to seed plants (gymnosperms and angiosperms).