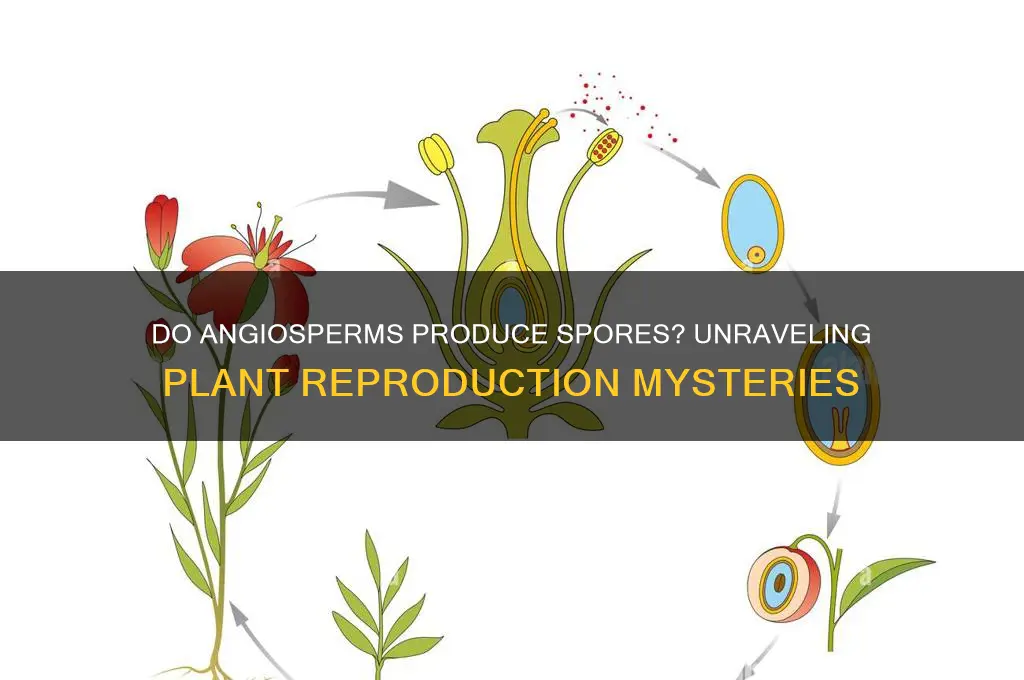

Angiosperms, commonly known as flowering plants, are a diverse group of plants characterized by their production of flowers and fruits. Unlike non-vascular plants such as ferns and mosses, which reproduce via spores, angiosperms primarily reproduce through seeds. These seeds develop from the ovules after fertilization, a process that occurs within the flower. While angiosperms do not produce spores as part of their primary reproductive cycle, they do generate spores during the alternation of generations in their life cycle, specifically in the form of microspores (which develop into pollen) and megaspores (which give rise to the female gametophyte). This distinction highlights the unique reproductive strategies of angiosperms compared to spore-producing plants, emphasizing their reliance on seeds for dispersal and survival.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do angiosperms produce spores? | No |

| Reproductive method | Seeds |

| Life cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte dominant) |

| Sporophyte phase | Dominant, long-lived (the plant we see) |

| Gametophyte phase | Reduced, dependent on sporophyte (pollen and embryo sac) |

| Type of reproduction | Sexual reproduction via flowers and seeds |

| Dispersal method | Seeds dispersed by wind, water, animals, or explosively |

| Examples | Roses, oaks, grasses, sunflowers |

| Contrast with spore-producing plants | Unlike ferns, mosses, and gymnosperms, angiosperms do not rely on spores for reproduction |

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Angiosperm Life Cycle Overview: Angiosperms reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns and mosses

- Spores in Non-Angiosperms: Ferns, mosses, and fungi use spores for asexual reproduction and dispersal

- Angiosperm Pollination Methods: Angiosperms rely on flowers, wind, or animals for pollination, not spore dispersal

- Seed vs. Spore Development: Seeds develop from fertilized ovules; spores are haploid reproductive cells

- Evolutionary Differences: Angiosperms evolved seeds for protection; spores are primitive reproductive structures

Angiosperm Life Cycle Overview: Angiosperms reproduce via seeds, not spores, unlike ferns and mosses

Angiosperms, commonly known as flowering plants, stand apart from ferns and mosses in their reproductive strategy. While ferns and mosses rely on spores to propagate, angiosperms have evolved a more complex and efficient method: seed production. This fundamental difference shapes their life cycles, ecological roles, and interactions with their environments. Seeds, unlike spores, contain an embryo, stored nutrients, and protective layers, enabling angiosperms to colonize diverse habitats and survive harsh conditions.

To understand this distinction, consider the life cycle of an angiosperm. It begins with pollination, where pollen from the male reproductive organ (stamen) fertilizes the female ovule (pistil). This process results in the formation of a seed within a fruit. The seed, a miniature time capsule, houses a dormant embryo, endosperm (nutrient storage), and a protective seed coat. When conditions are favorable, the seed germinates, giving rise to a new plant. This seed-based reproduction contrasts sharply with spore-based reproduction, where a single-celled spore develops into a gametophyte, which then produces gametes for fertilization.

From a practical standpoint, the seed-based life cycle of angiosperms has profound implications for agriculture, horticulture, and conservation. Seeds can be stored, transported, and sown with precision, making angiosperms ideal for crop cultivation. For example, wheat, rice, and corn—staples of global food systems—are all angiosperms. Their seeds are harvested, processed, and replanted seasonally, ensuring consistent yields. In contrast, spore-based plants like ferns and mosses are less predictable and harder to cultivate on a large scale, limiting their agricultural utility.

However, the reliance on seeds is not without challenges. Angiosperms require pollinators—bees, butterflies, birds, or wind—for successful reproduction. Declines in pollinator populations, driven by habitat loss and pesticide use, threaten angiosperm diversity and food security. Conservation efforts, such as creating pollinator-friendly habitats and reducing chemical inputs, are essential to sustain these vital relationships. Additionally, while seeds offer resilience, they are not invincible. Extreme weather, pests, and diseases can still disrupt germination and growth, underscoring the need for sustainable practices.

In summary, the angiosperm life cycle’s reliance on seeds, rather than spores, is a key evolutionary innovation. This adaptation has enabled angiosperms to dominate terrestrial ecosystems and become the foundation of human agriculture. Yet, their success hinges on delicate ecological balances, reminding us of the interconnectedness of life. By understanding and protecting these processes, we can ensure the continued prosperity of angiosperms and the countless species, including humans, that depend on them.

Do Spores Contain Diploid Cells? Unraveling the Genetic Makeup

You may want to see also

Spores in Non-Angiosperms: Ferns, mosses, and fungi use spores for asexual reproduction and dispersal

Ferns, mosses, and fungi rely on spores as their primary method of asexual reproduction and dispersal, a strategy that contrasts sharply with angiosperms, which produce seeds. Spores are lightweight, single-celled structures that can be carried by wind, water, or animals to colonize new environments. For example, ferns release spores from the undersides of their fronds, which germinate into tiny, heart-shaped gametophytes when conditions are favorable. This process bypasses the need for a mate, allowing rapid proliferation in suitable habitats.

Mosses, another non-angiosperm group, produce spores in capsules atop slender stalks called setae. These capsules dry out and split open, dispersing spores over considerable distances. Unlike seeds, spores require moisture to develop, which is why mosses thrive in damp, shaded environments. This dependency on water highlights a key limitation of spore-based reproduction but also explains their success in specific ecological niches.

Fungi, though distinct from plants, also utilize spores for reproduction and dispersal. For instance, mushrooms release billions of spores from their gills, each capable of growing into a new fungal organism. This sheer volume ensures that at least some spores land in environments conducive to growth. Fungal spores are remarkably resilient, surviving harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures and desiccation, which further enhances their dispersal potential.

Comparing these non-angiosperms reveals a common theme: spores are an efficient, low-energy method of reproduction and dispersal. They lack the protective coat and nutrient reserves of seeds, making them vulnerable but also highly adaptable. This trade-off allows ferns, mosses, and fungi to dominate environments where angiosperms struggle, such as dense forests, rocky outcrops, and decaying matter.

For gardeners or enthusiasts looking to cultivate these spore-producing organisms, understanding their life cycles is crucial. Ferns, for instance, require consistent moisture and indirect light for spore germination. Mosses can be encouraged to grow by maintaining damp soil and avoiding direct sunlight. Fungi, particularly mushrooms, thrive in organic-rich substrates like compost or wood chips. By mimicking their natural habitats, one can successfully propagate these non-angiosperms and appreciate their unique reproductive strategies.

Do Mushroom Spores Need Light? Unveiling the Truth for Successful Growth

You may want to see also

Angiosperm Pollination Methods: Angiosperms rely on flowers, wind, or animals for pollination, not spore dispersal

Angiosperms, commonly known as flowering plants, have evolved sophisticated pollination strategies that set them apart from spore-dispersing organisms. Unlike ferns or fungi, which release spores into the wind for reproduction, angiosperms depend on flowers, wind, or animals to transfer pollen between individuals. This reliance on external agents ensures genetic diversity and efficient fertilization, making angiosperms the most diverse group of land plants. Understanding these methods reveals the intricate adaptations that have allowed them to dominate terrestrial ecosystems.

One of the most recognizable pollination methods is animal-mediated pollination, which involves insects, birds, bats, and even small mammals. Flowers have co-evolved with these pollinators, offering rewards like nectar, pollen, or shelter in exchange for pollen transfer. For instance, hummingbirds are attracted to tubular, red flowers rich in nectar, while bees favor open, brightly colored blooms with easily accessible pollen. Gardeners can enhance pollination by planting species like lavender, sunflowers, or bee balm, which are known to attract a variety of pollinators. To maximize success, ensure these plants are grouped together and bloom throughout the growing season to provide a continuous food source.

Wind pollination, another common method, is employed by grasses, oaks, and pines, among others. These plants produce lightweight, dry pollen grains that can be carried over long distances by air currents. While efficient, this method requires the production of vast quantities of pollen to increase the likelihood of fertilization. For those managing wind-pollinated species, such as corn or wheat, it’s essential to plant in blocks rather than rows to facilitate pollen interception. Additionally, avoid planting near areas with high wind turbulence, as this can disperse pollen away from the target area.

In contrast to spore dispersal, which is passive and relies on environmental conditions, angiosperm pollination is a targeted process. Flowers are not just reproductive structures but also signaling devices, using color, scent, and shape to attract specific pollinators. For example, night-blooming flowers like the moonflower emit strong fragrances to attract moths, while daytime blooms often rely on visual cues. This precision ensures that pollen is transferred efficiently, reducing waste and increasing the chances of successful reproduction.

While angiosperms do not produce spores, their seeds are the result of successful pollination and fertilization. Seeds are protected by fruits, which often rely on animals for dispersal, creating a two-step process that ensures both reproduction and distribution. This distinction highlights the advanced reproductive strategies of angiosperms, which have enabled them to colonize nearly every habitat on Earth. By studying and supporting these pollination methods, we can contribute to the health of ecosystems and the sustainability of agriculture.

Mold Spores and Sinus Infections: Uncovering the Hidden Connection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seed vs. Spore Development: Seeds develop from fertilized ovules; spores are haploid reproductive cells

Angiosperms, commonly known as flowering plants, are renowned for their seed-producing capabilities, a hallmark of their reproductive strategy. Unlike some other plant groups, angiosperms do not produce spores as part of their life cycle. Instead, their reproductive process centers around the development of seeds, which are the result of fertilization within the ovule. This distinction is fundamental to understanding the unique biology of angiosperms and their dominance in terrestrial ecosystems.

Seeds are the product of a complex process that begins with the fertilization of an ovule, a structure found within the ovary of a flower. Following fertilization, the ovule develops into a seed, which contains an embryo, stored food, and a protective coat. This process is a key feature of angiosperms and is responsible for their success in diverse environments. The seed provides a means for the plant to disperse its offspring and ensures the survival of the species through periods of unfavorable conditions.

In contrast, spores are haploid reproductive cells produced by plants such as ferns, mosses, and fungi. These cells are typically single-celled and are capable of developing into a new organism without fertilization. Spores are often lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, allowing the parent plant to propagate over a wide area. However, this method of reproduction lacks the protective and nutrient-rich environment provided by a seed, making spore-producing plants more vulnerable to environmental challenges.

The development of seeds in angiosperms offers several advantages over spore reproduction. Firstly, seeds provide a secure environment for the developing embryo, protecting it from desiccation, predation, and mechanical damage. Secondly, the stored food within the seed, such as endosperm or cotyledons, supplies the embryo with the necessary nutrients for initial growth, increasing the chances of survival in nutrient-poor soils. Lastly, seeds can remain dormant for extended periods, allowing plants to time their germination to coincide with favorable environmental conditions.

For gardeners and botanists, understanding the difference between seed and spore development is crucial for successful plant propagation. Angiosperms, with their seed-based reproduction, often require specific conditions for germination, such as adequate moisture, temperature, and light. In contrast, spore-producing plants may necessitate more controlled environments, like humid conditions for fern spore germination. By recognizing these distinctions, one can tailor propagation techniques to suit the unique reproductive strategies of different plant groups, ensuring healthier and more robust growth.

Exploring the Microscopic World: What Do Spores Really Look Like?

You may want to see also

Evolutionary Differences: Angiosperms evolved seeds for protection; spores are primitive reproductive structures

Angiosperms, or flowering plants, are distinguished by their production of seeds, a trait that marks a significant evolutionary leap from the more primitive reproductive method of spore dispersal. While non-seed plants like ferns and mosses rely on spores to reproduce, angiosperms encapsulate their offspring in seeds, providing a protective barrier against environmental stressors such as desiccation, predation, and mechanical damage. This innovation allowed angiosperms to colonize a wider range of habitats, contributing to their dominance in terrestrial ecosystems today. The seed’s structure—often containing stored nutrients and a protective coat—ensures the embryo’s survival until conditions are favorable for germination, a luxury spores do not afford.

To understand the evolutionary advantage of seeds, consider the reproductive cycle of spore-producing plants. Spores are lightweight, single-celled structures that disperse easily through wind or water but are highly vulnerable to environmental conditions. For instance, ferns release spores that must land in a moist environment to grow into gametophytes, which then produce eggs and sperm. This dependency on specific conditions limits their reproductive success compared to angiosperms, whose seeds can lie dormant for extended periods. A practical example is the desert angiosperm *Larrea tridentata*, which can remain dormant as a seed for decades before germinating after rare rainfall, a survival strategy spores cannot replicate.

From an analytical perspective, the evolution of seeds represents a shift from passive to active reproductive strategies. Spores rely on sheer numbers and environmental chance for survival, whereas seeds are equipped with mechanisms to enhance viability. For instance, some angiosperm seeds have hard coats that only allow germination after scarification (e.g., passing through an animal’s digestive tract) or exposure to fire, ensuring they sprout in nutrient-rich conditions. This adaptability highlights the seed’s role as an evolutionary innovation, not just a reproductive structure but a survival tool.

Instructively, gardeners and botanists can leverage this knowledge to improve plant propagation. For spore-bearing plants like ferns, creating a humid, shaded environment mimics their natural habitat, increasing the likelihood of successful germination. In contrast, angiosperm seeds often require specific treatments, such as stratification (cold treatment) for temperate species like *Acer saccharum* (sugar maple), to break dormancy. Understanding these differences allows for more effective cultivation practices, emphasizing the practical implications of evolutionary distinctions.

Persuasively, the seed’s evolutionary success underscores its role as a cornerstone of biodiversity. Angiosperms account for approximately 80% of all plant species, a statistic that reflects the seed’s transformative impact on plant survival and dispersal. By contrast, spore-producing plants are largely confined to specific niches, such as moist forests or aquatic environments. This disparity highlights the seed’s superiority as a reproductive structure, making a compelling case for its significance in the history of life on Earth. In essence, the seed is not just a product of evolution but a driver of it, shaping ecosystems and enabling the proliferation of plant life in ways spores cannot.

Troubleshooting Spore Registration Issues on Steam: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, angiosperms do not produce spores. They reproduce through seeds, which are the result of sexual reproduction involving flowers, pollination, and fertilization.

Angiosperms differ from spore-producing plants (like ferns and mosses) because they rely on seeds for reproduction, while spore-producing plants use spores for asexual reproduction and dispersal.

No, angiosperms do not have a spore-producing stage in their life cycle. Their life cycle is characterized by alternation of generations between a dominant sporophyte (the plant) and a reduced gametophyte (within the flower).