Bacillus is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria known for its remarkable ability to form highly resistant endospores, commonly referred to as spores. These spores are a key survival mechanism, allowing Bacillus species to endure harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. Unlike the vegetative cells, which are actively growing and metabolizing, spores are dormant, metabolically inactive forms that can remain viable for extended periods, sometimes even centuries. This sporulation process is a defining characteristic of Bacillus, distinguishing it from many other bacterial genera and contributing to its widespread presence in diverse environments, including soil, water, and even the gastrointestinal tracts of animals. Understanding whether Bacillus has spores is fundamental to appreciating its ecological significance, industrial applications, and potential health implications.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How and why Bacillus forms spores under stress conditions

- Spore Structure: Key components and layers of Bacillus spores

- Spore Resistance: Survival mechanisms of Bacillus spores in harsh environments

- Germination Triggers: Factors that activate Bacillus spore germination

- Spore Applications: Uses of Bacillus spores in industry and research

Sporulation Process: How and why Bacillus forms spores under stress conditions

Bacillus, a genus of Gram-positive bacteria, is renowned for its ability to form highly resistant spores under stress conditions. This process, known as sporulation, is a survival mechanism that allows the bacterium to endure harsh environments such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, and desiccation. Unlike vegetative cells, which are vulnerable to adverse conditions, spores can remain dormant for years, only to revive when conditions improve. This adaptability makes Bacillus a fascinating subject in microbiology and biotechnology.

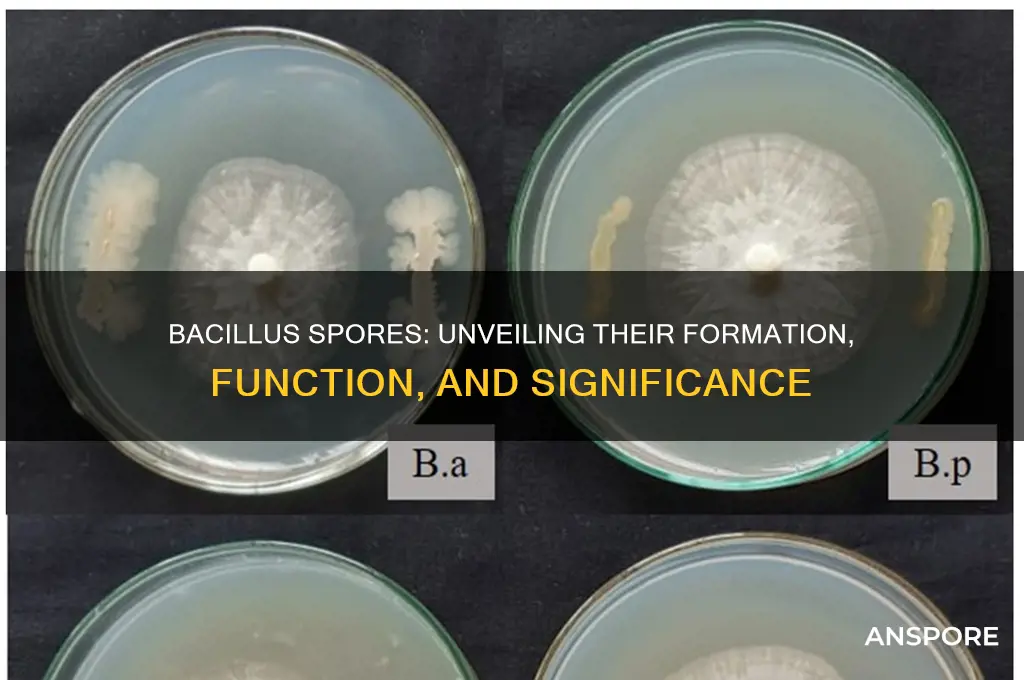

The sporulation process in Bacillus is a complex, multi-stage transformation that begins with the activation of specific genes in response to stress. When nutrients become scarce, the bacterium initiates a series of morphological changes. First, the cell replicates its DNA and then divides asymmetrically, forming a smaller cell (the forespore) within a larger mother cell. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, creating a double-membrane structure. Over time, the forespore develops a thick, protective coat composed of proteins, peptidoglycan, and other molecules, which confer resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals. This layer is crucial for the spore’s durability, enabling it to withstand conditions that would destroy vegetative cells.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporulation is essential for industries such as food preservation and healthcare. For instance, Bacillus spores can survive pasteurization temperatures (typically 63°C for 30 minutes), making them a concern in food processing. To eliminate spores, more extreme measures like autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) are required. Conversely, the resilience of Bacillus spores is harnessed in probiotics, where they can survive the gastrointestinal tract to deliver beneficial effects. Researchers are also exploring spore-based technologies for vaccine delivery and environmental cleanup, leveraging their stability and longevity.

Comparatively, sporulation in Bacillus differs from other bacterial survival strategies, such as biofilm formation or cyst development in parasites. While biofilms protect bacteria through collective resistance, spores offer individual cells a long-term survival option. This distinction highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of Bacillus, which prioritizes long-term persistence over immediate group protection. Such differences underscore the importance of tailoring antimicrobial strategies to the specific survival mechanisms of the target organism.

In conclusion, the sporulation process in Bacillus is a remarkable example of bacterial adaptability, driven by the need to survive stress conditions. By forming spores, Bacillus ensures its longevity in environments that would otherwise be lethal. This mechanism not only poses challenges in industries like food safety but also offers opportunities in biotechnology. Understanding the intricacies of sporulation is key to both mitigating its risks and harnessing its potential, making it a critical area of study in microbiology.

Do Cycads Have Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Key components and layers of Bacillus spores

Bacillus spores are renowned for their resilience, capable of withstanding extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. This durability stems from their intricate structure, which consists of multiple layers, each serving a specific protective function. Understanding these layers is crucial for appreciating how Bacillus spores can survive for decades, if not centuries, in harsh environments.

At the core of the spore lies the spore protoplast, which contains the bacterial genome, essential enzymes, and metabolic machinery. This central region is akin to a miniaturized bacterial cell, poised to resume growth once conditions become favorable. Surrounding the protoplast is the spore core wall, a robust structure that maintains the spore’s shape and protects its contents. The core wall is rich in peptidoglycan, a polymer that provides structural integrity while remaining flexible enough to accommodate rehydration during germination.

Encasing the core wall is the cortex, a thick layer composed primarily of peptidoglycan. The cortex plays a critical role in spore dehydration, as it is responsible for trapping calcium dipicolinate, a compound that helps stabilize the spore’s DNA during dormancy. During germination, the cortex is degraded, allowing water to reenter the spore and initiate metabolic activity. Beyond the cortex lies the spore coat, a proteinaceous layer that acts as the primary barrier against environmental stressors. The coat is highly impermeable, preventing the entry of enzymes, chemicals, and other damaging agents. Its composition varies among Bacillus species but typically includes keratin-like proteins and enzymes that aid in spore resistance.

The outermost layer is the exosporium, a thin, hair-like structure that surrounds the spore in some Bacillus species. The exosporium is involved in spore adhesion to surfaces and may contain proteins that interact with the environment. While not all Bacillus spores have an exosporium, its presence enhances the spore’s ability to survive in specific ecological niches. Together, these layers form a formidable defense system, ensuring that Bacillus spores can endure extreme conditions and reawaken when the environment becomes conducive to growth.

To illustrate the practical implications, consider the food industry, where Bacillus spores are a major concern in canning processes. Spores can survive pasteurization temperatures (typically 70–90°C), necessitating more aggressive methods like autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) to ensure their destruction. Understanding spore structure helps in designing effective sterilization protocols, ensuring food safety and shelf stability. Similarly, in biotechnology, the resilience of Bacillus spores is harnessed for applications like probiotic delivery and bioinsecticides, where their ability to remain dormant until activated is a key advantage.

Are Psilocybe Cubensis Spores Legal in California? A Guide

You may want to see also

Spore Resistance: Survival mechanisms of Bacillus spores in harsh environments

Bacillus spores are renowned for their extraordinary resilience, capable of withstanding conditions that would annihilate most life forms. These dormant structures, formed during nutrient deprivation, exhibit resistance to extreme temperatures, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. Understanding their survival mechanisms not only sheds light on microbial adaptability but also has practical implications for industries like food preservation, healthcare, and space exploration.

Bacillus spores owe their toughness to a multi-layered defense system. The outermost layer, the exosporium, acts as a protective shield, preventing direct contact with harmful agents. Beneath lies the spore coat, a robust structure composed of proteins and peptides that provides mechanical strength and chemical resistance. The cortex, rich in peptidoglycan, maintains spore dehydration and protects the core. Finally, the core itself, housing the bacterial genome and essential enzymes, is stabilized by dipicolinic acid (DPA), a molecule that binds calcium ions to form a lattice-like structure, further enhancing resistance.

One key survival strategy of Bacillus spores is their ability to enter a state of profound dormancy. This metabolic shutdown minimizes energy consumption and reduces vulnerability to environmental stressors. Spores can remain viable for decades, even centuries, in this dormant state, waiting for favorable conditions to reactivate. For instance, spores of *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, have been revived from sediments dating back to the 19th century. This remarkable longevity underscores the effectiveness of their survival mechanisms.

Practical applications of spore resistance are vast. In the food industry, understanding spore survival helps develop more effective sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, which is necessary to destroy spores of *Clostridium botulinum*. In healthcare, spore resistance informs the design of disinfectants and sterilization protocols for medical equipment. For space exploration, studying spore survival in extreme environments like Mars provides insights into the potential for extraterrestrial life and the risks of interplanetary contamination.

To combat spore resistance in unwanted contexts, such as food spoilage or infections, targeted strategies are essential. For example, combining heat treatment with chemical agents like hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid can enhance spore destruction. In clinical settings, antibiotics like vancomycin or linezolid are used to treat infections caused by spore-forming bacteria, though their effectiveness depends on the spore’s germination stage. For individuals handling spore-contaminated materials, wearing protective gear and following strict hygiene protocols is crucial to prevent exposure.

In conclusion, the survival mechanisms of Bacillus spores in harsh environments are a testament to the ingenuity of microbial life. By deciphering these mechanisms, we not only gain a deeper appreciation for the resilience of life but also unlock practical solutions to challenges in food safety, healthcare, and beyond. Whether harnessing their durability for beneficial purposes or combating their persistence in unwanted scenarios, understanding spore resistance is key to navigating the microbial world.

How Fungi Reproduce: The Role of Spores Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Germination Triggers: Factors that activate Bacillus spore germination

Bacillus species are renowned for their ability to form highly resistant spores, a survival mechanism that allows them to endure extreme conditions. However, these spores are not perpetually dormant; they can be activated under specific circumstances, a process known as germination. Understanding the triggers that initiate this transformation is crucial for various applications, from biotechnology to environmental management.

The Chemical Awakening: Nutrient Signaling

In the realm of Bacillus spore germination, certain chemicals act as potent stimulants. One of the most well-studied triggers is the presence of specific nutrients, particularly amino acids and sugars. For instance, L-valine, a branched-chain amino acid, is a powerful germinant for many Bacillus species, including *B. subtilis* and *B. cereus*. When spores detect a threshold concentration of L-valine, typically in the range of 1-10 mM, they initiate germination. This process is highly specific; different Bacillus species may respond to distinct amino acids or require unique combinations for activation. For example, *B. anthracis* spores are known to germinate in response to L-alanine and inosine, a nucleoside, rather than L-valine. This specificity is a fascinating adaptation, ensuring spores remain dormant until they encounter the precise conditions indicative of a favorable environment.

Environmental Cues: Temperature and pH

Beyond chemical signals, environmental factors play a pivotal role in triggering Bacillus spore germination. Temperature is a critical parameter, with many species exhibiting optimal germination within a specific range. For instance, *B. subtilis* spores germinate most efficiently at temperatures between 30°C and 50°C. This temperature-dependent activation is a strategic adaptation, allowing spores to remain dormant during extreme cold or heat and spring to life when conditions are more conducive to growth. Similarly, pH levels can influence germination. Some Bacillus species prefer slightly alkaline conditions, with a pH range of 7.5 to 8.5, for optimal germination. This preference is particularly relevant in natural environments, where pH fluctuations can signal the presence of nutrients or potential hosts.

The Role of Hydration: Water Activity and Pressure

Water is essential for life, and its availability is a critical factor in Bacillus spore germination. Spores require a certain level of hydration to initiate the germination process. This is often measured as water activity (aw), which represents the availability of water in a system. Most Bacillus spores germinate when aw exceeds 0.95, indicating a relatively humid environment. Interestingly, water pressure can also influence germination. High hydrostatic pressure, typically above 100 MPa, has been shown to induce germination in some Bacillus species, possibly by altering the spore's membrane integrity. This pressure-induced germination is a unique adaptation, allowing spores to respond to physical changes in their environment.

Practical Applications and Considerations

Understanding these germination triggers has practical implications. In biotechnology, controlled germination is essential for spore-based products, such as probiotics and biocontrol agents. For instance, in the production of spore-based probiotics, manufacturers can use specific nutrient triggers to ensure rapid and consistent germination in the gut, enhancing product efficacy. In environmental applications, knowing the precise conditions that activate spores can aid in developing strategies to manage Bacillus-related issues, such as food spoilage or pathogen control. For example, in the food industry, preventing the germination of *B. cereus* spores by controlling temperature and nutrient availability is crucial to ensuring food safety.

In summary, Bacillus spore germination is a complex process influenced by a myriad of factors, from specific chemical signals to environmental conditions. Each species has evolved unique responses to these triggers, ensuring their survival and proliferation in diverse habitats. By deciphering these germination codes, scientists can harness the power of Bacillus spores for various applications while also developing strategies to manage their impact in different contexts. This knowledge is a testament to the intricate relationship between microorganisms and their environment, where subtle cues can initiate profound transformations.

Exploring Omnivorous Diets in Spore: A Comprehensive Guide for Players

You may want to see also

Spore Applications: Uses of Bacillus spores in industry and research

Bacillus spores, renowned for their resilience, have become indispensable in various industrial and research applications. Their ability to withstand extreme conditions—heat, radiation, and desiccation—makes them ideal for processes requiring long-term stability and durability. From biotechnology to agriculture, these spores are engineered to perform tasks that conventional methods struggle to achieve.

In the realm of bioremediation, Bacillus spores are deployed to clean up environmental contaminants. For instance, strains like *Bacillus subtilis* are genetically modified to break down petroleum hydrocarbons in oil spills. A typical application involves dispersing spore-laden pellets at a rate of 10^6–10^8 spores per gram of contaminated soil. These spores germinate upon contact with nutrients, secreting enzymes that degrade pollutants. Studies show a 70–90% reduction in hydrocarbon levels within 4–6 weeks, making this method both efficient and cost-effective.

The probiotic industry leverages Bacillus spores to enhance gut health in humans and animals. Unlike lactic acid bacteria, Bacillus spores survive stomach acid and germinate in the intestines, delivering consistent benefits. Products like *Bacillus coagulans* are formulated into capsules containing 1–5 billion CFUs (colony-forming units) per dose. Clinical trials indicate improved digestion and immune function in adults aged 18–65, with minimal side effects. For livestock, spore-based feed additives reduce antibiotic use by 30–50%, promoting sustainable farming practices.

In agriculture, Bacillus spores serve as biofertilizers and biopesticides, reducing reliance on chemical inputs. Strains like *Bacillus thuringiensis* produce proteins toxic to pests but harmless to humans and plants. Farmers apply spore suspensions at 10^8–10^10 CFUs per liter of water, achieving pest control with a single application. Similarly, spore-based biofertilizers enhance nutrient uptake in crops like wheat and rice, increasing yields by 15–25%. These applications align with organic farming standards, making them popular among eco-conscious growers.

Finally, research utilizes Bacillus spores as model systems for studying stress resistance and cellular mechanisms. Their ability to remain dormant for decades provides insights into DNA repair and metabolic shutdown. Scientists expose spores to gamma radiation or extreme temperatures, analyzing their survival rates to develop theories on astrobiology and extremophile biology. Such studies have practical implications, informing the design of radiation-resistant materials and long-term food preservation methods.

In summary, Bacillus spores are not just biological curiosities but powerful tools with diverse applications. Their unique properties enable innovations in environmental cleanup, health, agriculture, and scientific discovery, showcasing their potential to address global challenges.

Buying Magic Mushroom Spores in Australia: Legalities and Options Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Bacillus is a genus of bacteria known for its ability to form highly resistant endospores, commonly referred to as spores.

Bacillus spores serve as a survival mechanism, allowing the bacteria to withstand harsh environmental conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation.

While most Bacillus species are spore-forming, there are a few exceptions. However, the majority are known for their ability to produce spores.

Bacillus spores are dormant, highly resistant structures, whereas vegetative cells are actively growing and metabolizing but more susceptible to environmental stress.

Bacillus spores are extremely resilient and require extreme conditions, such as high temperatures (e.g., autoclaving) or specific chemicals, to be effectively destroyed.