Bacillus species are known for their ability to form highly resistant endospores, which allow them to survive harsh environmental conditions. One common medium used to isolate and identify Bacillus species is bicarbonate agar, which is particularly selective for Bacillus anthracis due to its alkaline pH and the presence of bicarbonate. The question of whether Bacillus spores can grow on bicarbonate agar is significant, as it relates to both the identification of specific Bacillus species and the understanding of their growth requirements. Bicarbonate agar supports the growth of Bacillus spores by providing an environment that mimics their natural habitat, often alkaline soils, and includes nutrients that promote spore germination and vegetative growth. This medium is also used in diagnostic laboratories to differentiate Bacillus anthracis from other Bacillus species based on characteristic colony morphology and biochemical reactions. Therefore, the ability of Bacillus spores to grow on bicarbonate agar is not only a fundamental aspect of their biology but also a critical tool in microbiological research and clinical diagnostics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Growth on Bicarbonate Agar | Bacillus species, particularly Bacillus anthracis, can grow on bicarbonate agar. |

| Purpose of Bicarbonate Agar | Used as a selective medium for isolating Bacillus anthracis due to its ability to utilize bicarbonate as a carbon source. |

| Appearance of Colonies | Bacillus anthracis typically forms small, grayish-white, non-hemolytic colonies with a ground-glass appearance. |

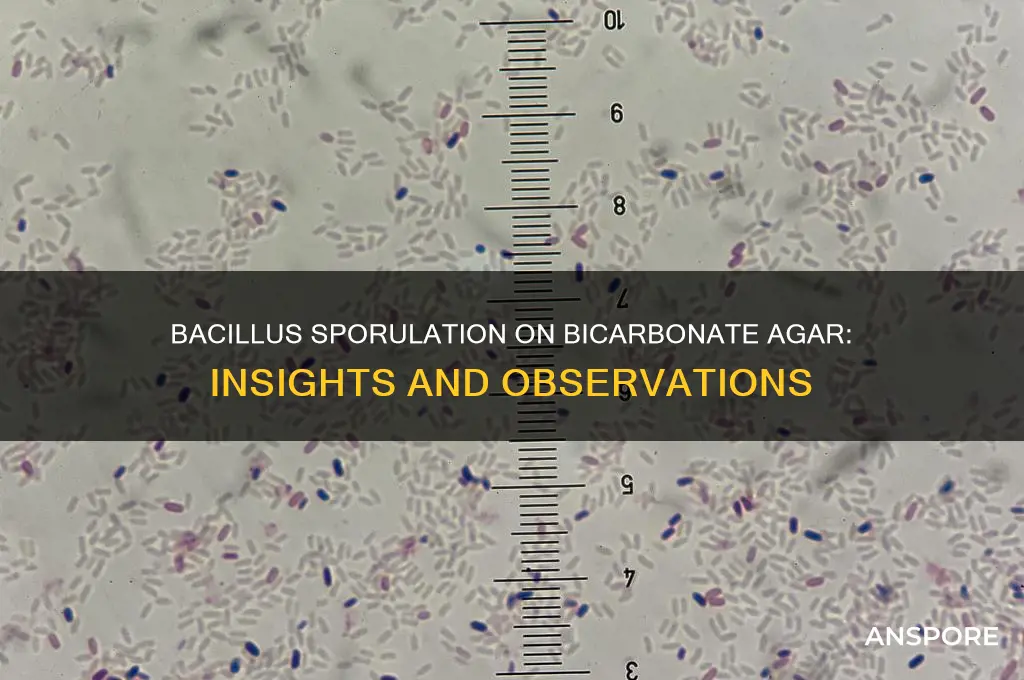

| Spore Formation | Bacillus species, including B. anthracis, are known for their ability to form endospores, which can be observed under a microscope. |

| Spore Staining | Spores can be visualized using specialized staining techniques, such as the Schaeffer-Fulton or Dorner methods. |

| Selective Properties | Bicarbonate agar inhibits the growth of most other bacteria, allowing for the selective isolation of Bacillus species. |

| pH Indicator | The agar often contains a pH indicator (e.g., phenol red) that changes color in response to acid production, aiding in identification. |

| Incubation Conditions | Typically incubated at 35-37°C for 18-24 hours to observe growth and characteristic colony morphology. |

| Applications | Primarily used in clinical and environmental laboratories for the detection and isolation of Bacillus anthracis, the causative agent of anthrax. |

| Limitations | While selective, bicarbonate agar may not completely inhibit all non-Bacillus species, requiring further confirmatory tests. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Conditions: Optimal pH, temperature, and bicarbonate concentration for Bacillus spore formation on bicarbonate agar

- Nutrient Requirements: Essential nutrients and bicarbonate’s role in supporting Bacillus spore development on agar

- Spore Viability Testing: Methods to assess Bacillus spore viability and longevity on bicarbonate agar

- Inhibition Factors: Factors like contaminants or additives that hinder Bacillus spore formation on bicarbonate agar

- Applications in Research: Use of bicarbonate agar for studying Bacillus spore characteristics and applications in microbiology

Spore Formation Conditions: Optimal pH, temperature, and bicarbonate concentration for Bacillus spore formation on bicarbonate agar

Bacillus species are renowned for their ability to form highly resistant endospores under adverse environmental conditions. When cultivating these spores on bicarbonate agar, understanding the optimal pH, temperature, and bicarbonate concentration is crucial for successful spore formation. Bicarbonate agar, typically composed of nutrients and sodium bicarbonate, provides a buffer system that helps maintain a stable pH, which is essential for spore development. However, not all Bacillus strains respond identically, and precise conditions must be tailored to the species in question.

Optimal pH for Spore Formation: Bacillus species generally thrive in slightly alkaline conditions, with a pH range of 7.5 to 8.5 being ideal for spore formation on bicarbonate agar. This pH range mimics the natural environment where many Bacillus species are found, such as soil and aquatic systems. Deviations from this range can inhibit sporulation, as extreme acidity or alkalinity disrupts the metabolic processes necessary for spore development. For instance, a pH below 7.0 may hinder the activity of key enzymes involved in sporulation, while a pH above 9.0 can denature proteins essential for the process.

Temperature Requirements: Temperature plays a pivotal role in sporulation, with most Bacillus species forming spores optimally between 30°C and 37°C. This mesophilic range aligns with the temperatures at which these bacteria are commonly found in nature. Lower temperatures, such as 25°C, may slow down sporulation, while higher temperatures, above 40°C, can be detrimental, potentially killing vegetative cells before sporulation occurs. For example, Bacillus subtilis, a well-studied model organism, exhibits peak sporulation efficiency at 37°C, making it a benchmark for laboratory conditions.

Bicarbonate Concentration and Its Role: The concentration of bicarbonate in the agar is critical for maintaining the optimal pH and providing a buffer system that stabilizes the environment. A typical bicarbonate agar recipe includes 0.5% to 1.0% sodium bicarbonate, which ensures the pH remains within the desired range throughout the incubation period. Too little bicarbonate may result in pH fluctuations, while excessive amounts can lead to osmotic stress, inhibiting spore formation. Practical tips include monitoring the pH of the agar before inoculation and adjusting the bicarbonate concentration if necessary to ensure it falls within the optimal range.

Practical Considerations and Troubleshooting: When preparing bicarbonate agar for Bacillus spore formation, it is essential to sterilize the medium properly to avoid contamination. Autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes is standard practice. After inoculation, incubate the plates for 48 to 72 hours to allow sufficient time for sporulation. If sporulation is not observed, consider reevaluating the pH, temperature, and bicarbonate concentration. For instance, if spores are absent, check if the pH has drifted outside the optimal range or if the incubation temperature was too high or too low. Adjusting these parameters based on the specific Bacillus species being cultured can significantly improve results.

In summary, successful spore formation of Bacillus on bicarbonate agar hinges on precise control of pH, temperature, and bicarbonate concentration. By maintaining a pH between 7.5 and 8.5, incubating at 30°C to 37°C, and using 0.5% to 1.0% sodium bicarbonate, researchers can optimize conditions for robust sporulation. Attention to these details ensures reliable and reproducible results, whether for laboratory studies or industrial applications.

Unveiling Botulism Spores: Appearance, Characteristics, and Identification Guide

You may want to see also

Nutrient Requirements: Essential nutrients and bicarbonate’s role in supporting Bacillus spore development on agar

Bacillus spores are renowned for their resilience, capable of surviving extreme conditions. However, their development on agar requires specific nutrients and environmental cues. Bicarbonate, often included in agar formulations, plays a pivotal role in supporting spore germination and outgrowth by maintaining pH stability and providing essential carbon sources.

Essential Nutrients for Bacillus Spore Development

Bacillus spores demand a precise blend of nutrients to transition from dormancy to active growth. Key components include nitrogen sources like ammonium or peptone, which fuel protein synthesis, and carbon sources such as glucose or glycerol for energy metabolism. Trace elements like magnesium, manganese, and iron are also critical, acting as cofactors for enzymatic reactions. Notably, bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) serves dual functions: it acts as a buffer to stabilize pH, typically maintaining an optimal range of 7.0–7.5, and provides a supplementary carbon source for metabolic processes. Without these nutrients, spores may remain dormant or fail to germinate effectively.

Bicarbonate’s Role in Spore Germination

Bicarbonate is not merely a buffer; it actively participates in spore activation. During germination, Bacillus spores release dipicolinic acid (DPA), a process that lowers pH and triggers metabolic reawakening. Bicarbonate neutralizes this acidity, ensuring the environment remains conducive to growth. Additionally, bicarbonate enhances the availability of carbon dioxide, which some Bacillus species utilize for energy production via pathways like the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. For optimal results, bicarbonate concentrations in agar typically range from 0.5% to 1.0%, balancing pH regulation and nutrient provision without inhibiting growth.

Practical Tips for Agar Preparation

When preparing bicarbonate agar for Bacillus spore studies, precision is key. Start by dissolving 1.0 g of sodium bicarbonate per 100 mL of agar to achieve a 1% concentration. Autoclave the medium at 121°C for 15 minutes to sterilize while preserving bicarbonate stability. Allow the agar to cool to 50–55°C before pouring plates to prevent nutrient degradation. For spore inoculation, use a sterile loop or pipette to transfer a small aliquot (10–50 μL) of spore suspension onto the agar surface. Incubate at 30–37°C for 24–48 hours, monitoring for colony formation. Avoid excessive bicarbonate, as concentrations above 2% can inhibit growth due to osmotic stress.

Comparative Analysis: Bicarbonate vs. Alternative Buffers

While bicarbonate is widely used, alternative buffers like phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or Tris-HCl can also support Bacillus spore development. However, bicarbonate offers distinct advantages. Unlike PBS, which lacks a carbon source, bicarbonate provides both buffering capacity and metabolic support. Tris-HCl, though effective for pH control, can interfere with nutrient availability at high concentrations. Bicarbonate’s dual role makes it a preferred choice for agar formulations, particularly in studies focusing on spore germination and outgrowth dynamics. Its simplicity and effectiveness ensure reliable results in both research and diagnostic settings.

Takeaway: Optimizing Conditions for Bacillus Spore Studies

Understanding the interplay between essential nutrients and bicarbonate is crucial for successful Bacillus spore cultivation on agar. By providing a balanced nutrient profile and maintaining optimal pH, bicarbonate agar creates an environment conducive to spore activation and growth. Researchers and practitioners should tailor bicarbonate concentrations and incubation conditions to specific Bacillus species, ensuring robust and reproducible results. This knowledge not only advances microbiological research but also enhances applications in biotechnology, food safety, and environmental monitoring.

Exploring Spore: Can You Discover Earth in This Cosmic Simulation?

You may want to see also

Spore Viability Testing: Methods to assess Bacillus spore viability and longevity on bicarbonate agar

Bacillus spores are renowned for their resilience, capable of surviving extreme conditions, but assessing their viability and longevity on bicarbonate agar requires precise methods. Bicarbonate agar, often used for cultivating bacteria in a slightly alkaline environment, presents a unique substrate for spore viability testing. The challenge lies in distinguishing between viable spores and those that have lost their ability to germinate, a critical distinction in fields like food safety, pharmaceuticals, and environmental monitoring.

Methods for Spore Viability Testing on Bicarbonate Agar

One widely adopted method is the heat-shock activation technique, where spores are exposed to temperatures of 70–80°C for 10–30 minutes before plating on bicarbonate agar. This step stimulates germination by breaking spore dormancy, allowing viable spores to initiate growth. After incubation at 37°C for 24–48 hours, colony-forming units (CFUs) are counted to quantify viability. Another approach involves direct plating without heat activation, followed by extended incubation (up to 72 hours) to capture slower-germinating spores. Both methods require careful standardization to avoid false negatives or positives.

Analytical Considerations and Limitations

While bicarbonate agar supports spore germination, its alkaline pH (around 8.4) can inhibit some Bacillus species, necessitating species-specific optimization. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores typically exhibit robust growth, whereas *Bacillus cereus* may require additional nutrients like glucose or peptone. False negatives can arise from suboptimal incubation conditions, such as temperatures below 30°C or inadequate humidity. Conversely, over-incubation may lead to false positives due to non-specific bacterial growth. Calibrating these variables is essential for accurate results.

Practical Tips for Enhanced Accuracy

To improve reliability, incorporate positive and negative controls in every assay. Use a known viable spore suspension as a positive control and a heat-killed (121°C, 15 minutes) spore suspension as a negative control. Additionally, serial dilution plating (e.g., 10^-3 to 10^-6 dilutions) helps avoid overcrowding and ensures accurate CFU counting. For longevity studies, periodically sample stored spores (e.g., weekly or monthly) and test viability on fresh bicarbonate agar to track survival rates over time. Document storage conditions (temperature, humidity, light exposure) to correlate environmental factors with viability decline.

Innovative Approaches and Future Directions

Emerging techniques like fluorescence microscopy with viability dyes (e.g., propidium iodide or SYTO 9) offer real-time assessment of spore integrity on bicarbonate agar, bypassing the need for CFU counting. These methods distinguish between intact and compromised spores, providing deeper insights into viability mechanisms. Integrating omics technologies, such as transcriptomics or proteomics, could further elucidate how bicarbonate agar influences spore germination and longevity. As these tools evolve, they promise to refine spore viability testing, ensuring greater precision in both research and industrial applications.

Unlocking Gut Health: Understanding Spore-Based Probiotics and Their Benefits

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Inhibition Factors: Factors like contaminants or additives that hinder Bacillus spore formation on bicarbonate agar

Bacillus spore formation on bicarbonate agar is a delicate process influenced by various environmental and chemical factors. Among these, contaminants and additives play a pivotal role in either facilitating or inhibiting spore development. Understanding these inhibition factors is crucial for researchers and microbiologists aiming to optimize spore production for applications in biotechnology, agriculture, and medicine.

One significant inhibitor is the presence of heavy metal contaminants, such as lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), and cadmium (Cd). Even at low concentrations (e.g., 10–50 ppm), these metals can disrupt the cellular metabolism of Bacillus species, impairing their ability to form spores. For instance, lead ions interfere with enzyme activity, particularly those involved in DNA replication and cell division, which are essential for sporulation. To mitigate this, ensure that all laboratory equipment and reagents are free from heavy metal residues, and consider using chelating agents like EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) at a concentration of 0.1–0.5 mM to bind and neutralize these contaminants.

Another critical factor is the pH imbalance caused by additives or contaminants. Bicarbonate agar typically maintains a slightly alkaline pH (around 8.4), which is optimal for Bacillus spore formation. However, acidic contaminants or additives can lower the pH, inhibiting sporulation. For example, acetic acid or lactic acid, even at concentrations as low as 0.1%, can significantly reduce spore viability. To counteract this, monitor the pH of the agar medium using a calibrated pH meter and adjust it with sterile sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or hydrochloric acid (HCl) solutions as needed. Additionally, avoid using acidic preservatives or cleaning agents in the laboratory environment.

Organic solvents, commonly found in laboratory settings, are another class of inhibitors. Solvents like ethanol, acetone, and chloroform can permeate cell membranes, disrupting lipid bilayers and interfering with spore formation. Even residual amounts (e.g., 0.01–0.1%) can have detrimental effects. To minimize their impact, ensure all glassware and equipment are thoroughly rinsed with sterile distilled water and dried in a laminar flow hood before use. Alternatively, consider using solvent-free alternatives or employing a vacuum desiccator to remove traces of solvents from the agar medium.

Lastly, microbial contaminants, particularly fungi and competing bacteria, can outcompete Bacillus species for nutrients and produce inhibitory metabolites. For example, Penicillium fungi secrete penicillin, a known inhibitor of bacterial cell wall synthesis, which can halt sporulation. To prevent contamination, maintain strict aseptic techniques, including autoclaving all media and equipment at 121°C for 15 minutes. Additionally, incorporate antibiotics like cycloheximide (50–100 µg/mL) into the agar to selectively inhibit fungal growth without affecting Bacillus species.

In summary, inhibiting factors such as heavy metals, pH imbalances, organic solvents, and microbial contaminants can significantly hinder Bacillus spore formation on bicarbonate agar. By identifying and addressing these factors through careful monitoring, appropriate additives, and stringent laboratory practices, researchers can enhance spore yield and reliability for various applications.

Sewing Psilocybin Spores: Compatibility with Various Grow Kits Explained

You may want to see also

Applications in Research: Use of bicarbonate agar for studying Bacillus spore characteristics and applications in microbiology

Bicarbonate agar serves as a specialized medium for cultivating and studying Bacillus spores due to its alkaline pH, typically ranging from 8.4 to 8.6. This pH mimics the environment in which many Bacillus species thrive, promoting spore germination and vegetative growth. Researchers often use this medium to isolate and enumerate Bacillus spores from environmental samples, such as soil or water, where these organisms are prevalent. The agar’s composition, which includes sodium bicarbonate as a buffering agent, ensures stability under aerobic conditions, making it ideal for studying spore viability and resistance mechanisms.

To effectively study Bacillus spores on bicarbonate agar, follow these steps: prepare the medium by dissolving 20 grams of nutrient agar and 10 grams of sodium bicarbonate in 1 liter of distilled water, sterilize via autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, and pour into sterile Petri dishes. Inoculate the agar with the sample containing Bacillus spores, incubate at 37°C for 24–48 hours, and observe colony morphology. For spore-specific studies, heat-shock the sample at 80°C for 10 minutes before inoculation to eliminate vegetative cells, ensuring only spores germinate. This method enhances the accuracy of spore-focused research.

A comparative analysis reveals that bicarbonate agar outperforms standard nutrient agar in Bacillus spore studies due to its pH-specific advantages. While nutrient agar supports general bacterial growth, bicarbonate agar selectively favors Bacillus species, particularly spore-forming strains like *Bacillus subtilis* and *Bacillus cereus*. This selectivity is critical for applications in food microbiology, where Bacillus spores are common contaminants. For instance, bicarbonate agar is used to assess spore survival in pasteurized milk, with studies showing a 90% reduction in spore count after heat treatment at 72°C for 15 seconds.

The persuasive case for using bicarbonate agar lies in its ability to simulate real-world conditions for Bacillus spores. Its alkaline pH mimics environments like the gastrointestinal tract, where Bacillus spores must germinate to cause infection. This makes bicarbonate agar invaluable in pathogenicity studies and vaccine development. For example, researchers use this medium to test spore resistance to antimicrobial agents, such as chlorine (0.5–1.0 ppm), commonly used in water treatment. The medium’s reliability in predicting spore behavior under stress conditions underscores its utility in applied microbiology.

In conclusion, bicarbonate agar is a cornerstone in Bacillus spore research, offering a pH-optimized environment for studying germination, resistance, and applications in food safety and medicine. Its specificity and ease of use make it a preferred choice over generic media, enabling precise investigations into spore characteristics. By incorporating practical techniques and comparative insights, researchers can leverage bicarbonate agar to advance our understanding of Bacillus spores and their implications in various fields.

Understanding the Meaning of 'Spor' in Ancient Roman Culture and Language

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Bicarbonate agar is a nutrient-rich medium that contains sodium bicarbonate, which acts as a pH buffer. It is used for Bacillus spore testing because it supports spore germination and bacterial growth, allowing for the isolation and identification of Bacillus species.

Yes, Bacillus spores can survive and germinate on bicarbonate agar. The medium provides the necessary nutrients and conditions for spore activation, growth, and colony formation, making it suitable for detecting and culturing Bacillus species.

Positive results are indicated by the presence of characteristic Bacillus colonies, which are typically large, irregular, and may exhibit a haze around the colony due to toxin production. Negative results show no growth, confirming the absence of viable Bacillus spores in the sample.