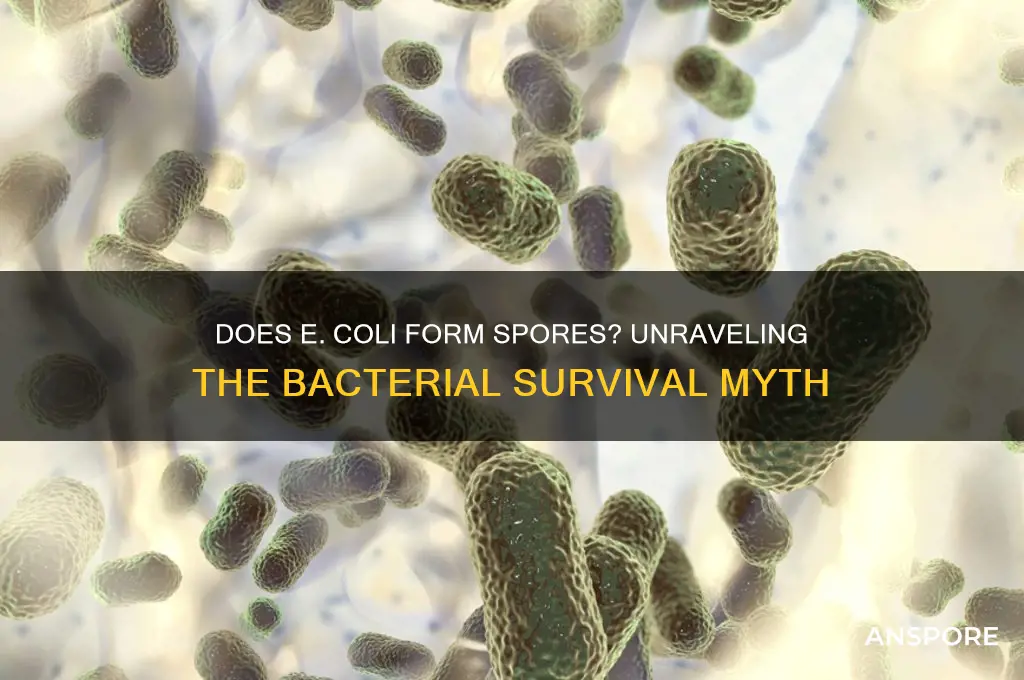

*Escherichia coli* (*E. coli*), a well-known bacterium commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals, is frequently studied for its role in both normal gut function and as a pathogen. One common question regarding *E. coli* is whether it forms spores, a dormant and highly resistant structure produced by some bacteria to survive harsh environmental conditions. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium* or *Bacillus*, *E. coli* does not produce spores under any circumstances. Instead, it relies on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and genetic adaptability, to endure challenging environments. Understanding this distinction is crucial, as it highlights the differences in survival strategies among bacterial species and informs approaches to controlling *E. coli* in clinical, industrial, and environmental settings.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does E. coli form spores? | No |

| Reason for non-spore formation | E. coli is a non-spore-forming bacterium, belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. It lacks the genetic and physiological mechanisms required for sporulation. |

| Survival strategies | E. coli relies on other mechanisms for survival in harsh conditions, such as biofilm formation, stress response systems, and the ability to enter a dormant state (e.g., stationary phase). |

| Comparison to spore-forming bacteria | Unlike spore-forming bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium), E. coli does not produce highly resistant endospores, making it more susceptible to environmental stressors like heat, desiccation, and disinfectants. |

| Relevance in food safety | The non-spore-forming nature of E. coli is important in food safety, as it is less likely to survive extreme processing conditions compared to spore-forming pathogens. |

| Laboratory identification | E. coli can be differentiated from spore-forming bacteria through spore staining techniques (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton stain), where E. coli will not stain as spore-positive. |

| Genetic basis | E. coli lacks the sporulation-specific genes (e.g., spo0A, sigE) found in spore-forming bacteria, which are essential for spore development. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- E. coli's Life Cycle: E. coli reproduces asexually, lacks spore formation, and divides by binary fission

- Spore Formation in Bacteria: Spores are survival structures; E. coli does not produce spores under stress

- E. coli Survival Mechanisms: E. coli survives via biofilms, stress proteins, and DNA repair, not sporulation

- Comparison with Spore-Forming Bacteria: Unlike Bacillus or Clostridium, E. coli lacks sporulation genes and mechanisms

- Environmental Stress Response: E. coli responds to stress with dormancy or lysis, not spore development

E. coli's Life Cycle: E. coli reproduces asexually, lacks spore formation, and divides by binary fission

E. coli, a bacterium commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals, follows a straightforward life cycle centered around asexual reproduction. Unlike some bacteria, such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, E. coli does not form spores. This absence of spore formation is a defining characteristic that influences its survival strategies and environmental interactions. Instead, E. coli relies on binary fission, a rapid and efficient method of reproduction, to thrive in its preferred habitats.

Binary fission in E. coli is a highly regulated process that begins with DNA replication, followed by cell elongation and division. Under optimal conditions, such as those found in the gut (temperature around 37°C and nutrient-rich environment), E. coli can double its population every 20 minutes. This rapid reproduction allows it to quickly colonize its environment but also makes it vulnerable to harsh conditions, as it lacks the protective spore stage. For instance, exposure to temperatures above 60°C or disinfectants like bleach can swiftly eliminate E. coli populations.

The lack of spore formation in E. coli has practical implications, particularly in food safety and healthcare. Since E. coli cannot form spores, it is less likely to survive long-term in adverse environments, such as dried surfaces or highly acidic foods. However, its ability to multiply rapidly in favorable conditions underscores the importance of proper hygiene and food handling practices. For example, cooking ground beef to an internal temperature of 71°C (160°F) effectively kills E. coli, while washing hands with soap for at least 20 seconds reduces transmission risk.

Comparatively, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* can survive extreme conditions, making them more challenging to eradicate. E. coli’s inability to form spores simplifies its control but requires vigilance in environments where it can thrive. In laboratory settings, E. coli’s asexual reproduction and lack of spore formation make it a preferred model organism for genetic studies, as its life cycle is predictable and easy to manipulate. Researchers often use nutrient-rich media like LB broth to cultivate E. coli, ensuring optimal growth conditions for experiments.

In summary, E. coli’s life cycle is marked by asexual reproduction through binary fission and the absence of spore formation. This simplicity makes it both a valuable research tool and a manageable pathogen in controlled environments. However, its rapid multiplication in favorable conditions necessitates strict hygiene practices to prevent contamination and infection. Understanding these specifics allows for targeted strategies to control E. coli, whether in a laboratory, kitchen, or clinical setting.

Alcohol's Power: Can 95% Concentration Inactivate Biological Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore Formation in Bacteria: Spores are survival structures; E. coli does not produce spores under stress

Bacteria have evolved remarkable strategies to endure harsh conditions, and spore formation is one of their most effective survival mechanisms. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow certain bacteria to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus anthracis* form spores that can persist in soil for decades, only to germinate when conditions become favorable. This ability underscores the importance of spores as a survival tool in the microbial world. However, not all bacteria possess this capability, and understanding which species do—and which do not—is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications.

Among the myriad bacterial species, *Escherichia coli* (*E. coli*) stands out as a well-studied organism, yet it lacks the ability to form spores. Despite its resilience in various environments, *E. coli* relies on other mechanisms to survive stress, such as biofilm formation and genetic adaptation. This distinction is significant because spore-forming bacteria pose unique challenges in food safety, healthcare, and environmental management. For example, while *E. coli* contamination in food can cause illness, it is typically eliminated by standard cooking temperatures. In contrast, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium perfringens* require higher temperatures (above 121°C) or longer exposure to heat to ensure destruction.

The absence of spore formation in *E. coli* has practical implications for laboratory and industrial settings. Researchers often use *E. coli* as a model organism precisely because it does not form spores, simplifying experiments and reducing biosafety concerns. In biotechnology, *E. coli* is a preferred host for producing recombinant proteins, as spore formation could complicate purification processes. However, this lack of sporulation also limits its use in studies of spore-specific mechanisms, such as germination or resistance to antibiotics. Understanding these limitations helps scientists choose the right bacterial species for their research objectives.

From a comparative perspective, the inability of *E. coli* to form spores highlights the diversity of bacterial survival strategies. While spore-forming bacteria invest energy in creating durable structures, *E. coli* focuses on rapid replication and adaptability. This trade-off reflects the ecological niches these bacteria occupy: *E. coli* thrives in nutrient-rich environments like the gut, where sporulation is unnecessary, whereas spore-formers often inhabit unpredictable habitats. Recognizing these differences allows for targeted interventions, such as using specific disinfectants or storage conditions to control bacterial growth in different contexts.

In practical terms, knowing that *E. coli* does not produce spores simplifies risk management in food processing and healthcare. For instance, pasteurization at 72°C for 15 seconds effectively eliminates *E. coli* in milk, whereas spore-forming bacteria require more stringent methods like ultra-high temperature (UHT) treatment. Similarly, in clinical settings, the absence of spores in *E. coli* infections means that standard sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, are sufficient to decontaminate equipment. This knowledge not only ensures safety but also optimizes resources by avoiding unnecessary over-treatment.

Can a Single Spore Grow into a Plant? Exploring the Process

You may want to see also

E. coli Survival Mechanisms: E. coli survives via biofilms, stress proteins, and DNA repair, not sporulation

E. coli, a bacterium commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals, does not form spores as a survival mechanism. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Clostridium botulinum* or *Bacillus anthracis*, which encapsulate themselves in highly resistant spores to endure harsh conditions, E. coli relies on alternative strategies to ensure its persistence. This distinction is critical for understanding how E. coli thrives in diverse environments, from the gut to contaminated food and water.

One of E. coli's primary survival mechanisms is the formation of biofilms, which are structured communities of bacteria encased in a self-produced protective matrix. Biofilms shield E. coli from antibiotics, host immune responses, and environmental stressors like desiccation and pH changes. For example, in food processing plants, E. coli biofilms can adhere to surfaces, making them difficult to eradicate even with standard cleaning protocols. To combat this, industries often employ sanitizers containing chlorine (50–200 ppm) or quaternary ammonium compounds, but even these may require mechanical removal to fully eliminate biofilms.

Another key survival strategy is the production of stress proteins, which help E. coli withstand adverse conditions such as high temperatures, oxidative stress, and nutrient deprivation. For instance, heat-shock proteins like DnaK and GroEL are upregulated when E. coli is exposed to temperatures above 42°C, allowing it to survive in environments like undercooked meat or pasteurized milk. Similarly, oxidative stress proteins such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) neutralize reactive oxygen species, enabling E. coli to persist in aerobic environments. These proteins are particularly relevant in clinical settings, where E. coli infections can develop resistance to antibiotics by overexpressing stress-response genes.

E. coli also excels at DNA repair, a mechanism that ensures its genetic integrity in the face of mutagens like UV radiation or chemical disinfectants. The SOS response, a global DNA repair system, is activated when DNA damage occurs, allowing E. coli to repair its genome and continue replicating. This is especially concerning in healthcare, as DNA repair mechanisms contribute to antibiotic resistance. For example, E. coli strains with mutations in the *gyrA* gene, which encodes a target of fluoroquinolones, can survive antibiotic treatment by repairing the damage caused by these drugs.

In contrast to spore-forming bacteria, which can remain dormant for years, E. coli's survival mechanisms focus on active adaptation and resilience. While spores are a passive, long-term survival strategy, E. coli's biofilms, stress proteins, and DNA repair systems enable it to actively respond to immediate threats. This difference has practical implications: spore-formers require extreme measures like autoclaving (121°C, 15 psi for 15 minutes) for inactivation, whereas E. coli can often be controlled with less aggressive methods, such as proper cooking (75°C for 1 minute) or effective sanitation protocols. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for preventing E. coli contamination in food, water, and healthcare settings.

Effective Ways to Eliminate Airborne Mold Spores in Your Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.25

Comparison with Spore-Forming Bacteria: Unlike Bacillus or Clostridium, E. coli lacks sporulation genes and mechanisms

E. coli, a bacterium commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals, stands in stark contrast to spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. While the latter possess the remarkable ability to form highly resistant spores under adverse conditions, E. coli lacks the genetic machinery necessary for sporulation. This fundamental difference in survival strategies has significant implications for their behavior in environments ranging from food processing plants to healthcare settings.

Consider the sporulation process in *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied model organism. When nutrients become scarce, this bacterium initiates a complex genetic program involving over 50 genes, culminating in the formation of a spore encased in multiple protective layers. These spores can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical disinfectants, often surviving for years. In contrast, E. coli relies solely on its vegetative form, which is far more susceptible to environmental stresses. For instance, while *Bacillus* spores can survive pasteurization temperatures (72°C for 15 seconds), E. coli is typically inactivated at these conditions, making it less of a concern in properly processed foods.

From a practical standpoint, this distinction is critical in food safety and medical contexts. Spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Clostridium perfringens* pose significant risks due to their ability to survive standard cooking temperatures and germinate in favorable conditions, leading to foodborne illnesses. E. coli, however, is more easily controlled through proper hygiene and cooking practices. For example, heating food to an internal temperature of 75°C (165°F) effectively eliminates E. coli, whereas *Clostridium* spores may require temperatures exceeding 100°C under pressure (autoclaving) for complete inactivation.

The absence of sporulation genes in E. coli also influences its role in laboratory research. While *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* are often studied for their sporulation mechanisms and applications in biotechnology (e.g., spore-based vaccines), E. coli is a preferred model for genetic studies due to its rapid growth and well-characterized genome. However, this lack of sporulation limits its utility in scenarios requiring long-term survival or extreme resistance, such as environmental bioremediation or space exploration.

In summary, the inability of E. coli to form spores sets it apart from bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, shaping its ecological niche and practical management. Understanding this difference is essential for tailoring strategies to control these organisms, whether in preventing food contamination, treating infections, or advancing scientific research. While spore-formers present unique challenges due to their resilience, E. coli’s vulnerability offers opportunities for effective intervention through conventional methods.

Are Psilocybe Spores Purple? Unveiling the Truth About Mushroom Spores

You may want to see also

Environmental Stress Response: E. coli responds to stress with dormancy or lysis, not spore development

E. coli, a bacterium commonly found in the intestines of humans and animals, faces environmental stresses like nutrient depletion, temperature shifts, and pH changes. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus subtilis*, E. coli lacks the genetic machinery to produce spores. Instead, it employs two primary survival strategies: dormancy and lysis. Dormancy, or the stationary phase, involves slowing metabolic activity to conserve energy, while lysis, the breakdown of the cell, releases genetic material and nutrients that can benefit the bacterial population. These responses highlight E. coli's adaptability in harsh conditions without resorting to spore formation.

To understand why E. coli opts for dormancy or lysis, consider its ecological niche. As a facultative anaerobe thriving in nutrient-rich environments, it has evolved to exploit resources rapidly rather than invest energy in spore development. For instance, when nutrients are scarce, E. coli enters the stationary phase, reducing its growth rate and synthesizing stress-resistant proteins like Dps, which protect DNA from oxidative damage. This strategy allows it to persist until conditions improve. In contrast, lysis occurs under severe stress, such as exposure to antibiotics or phage infection, where sacrificing individual cells benefits the population by releasing public goods like enzymes or DNA.

From a practical standpoint, understanding E. coli's stress responses is crucial for industries like food safety and biotechnology. For example, in food processing, E. coli's ability to enter dormancy can lead to persistent contamination, as dormant cells may survive standard sanitization methods. To mitigate this, treatments combining heat (e.g., 70°C for 10 minutes) and chemical sanitizers (e.g., 200 ppm chlorine) are recommended to target both active and dormant cells. Similarly, in biotechnology, inducing controlled lysis in E. coli is used to extract proteins or plasmids, often achieved by adding lysozyme (100 µg/mL) or detergents like Triton X-100.

Comparatively, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* invest significant energy in spore development, which provides long-term survival in extreme conditions. E. coli's approach, however, is more immediate and resource-efficient, aligning with its role as an opportunistic colonizer. This difference underscores the trade-offs in bacterial survival strategies: spores offer durability but require substantial energy, while dormancy and lysis provide flexibility with minimal investment. For researchers and practitioners, recognizing these distinctions is key to predicting and controlling E. coli behavior in various environments.

In conclusion, E. coli's response to environmental stress—dormancy or lysis—reflects its evolutionary adaptation to transient, resource-rich habitats. While spore development offers long-term survival, E. coli's strategies prioritize rapid recovery and population-level benefits. This knowledge informs practical applications, from enhancing food safety protocols to optimizing biotechnological processes. By focusing on these mechanisms, we gain deeper insights into E. coli's resilience and its implications for human health and industry.

Exploring Pteridophytes: Do They Have Spore Capsules or Not?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, E. coli (Escherichia coli) does not form spores. It is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

E. coli lacks the genetic machinery required for sporulation, a process typically seen in other bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium.

While E. coli does not form spores, it can survive in harsh conditions by forming biofilms or entering a dormant state, though it is less resilient than spore-forming bacteria.

No, all known strains of E. coli are non-spore-forming. Sporulation is not a characteristic of this bacterial species.

![Substances screened for ability to reduce thermal resistance of bacterial spores 1959 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Z99EgARVL._AC_UL320_.jpg)