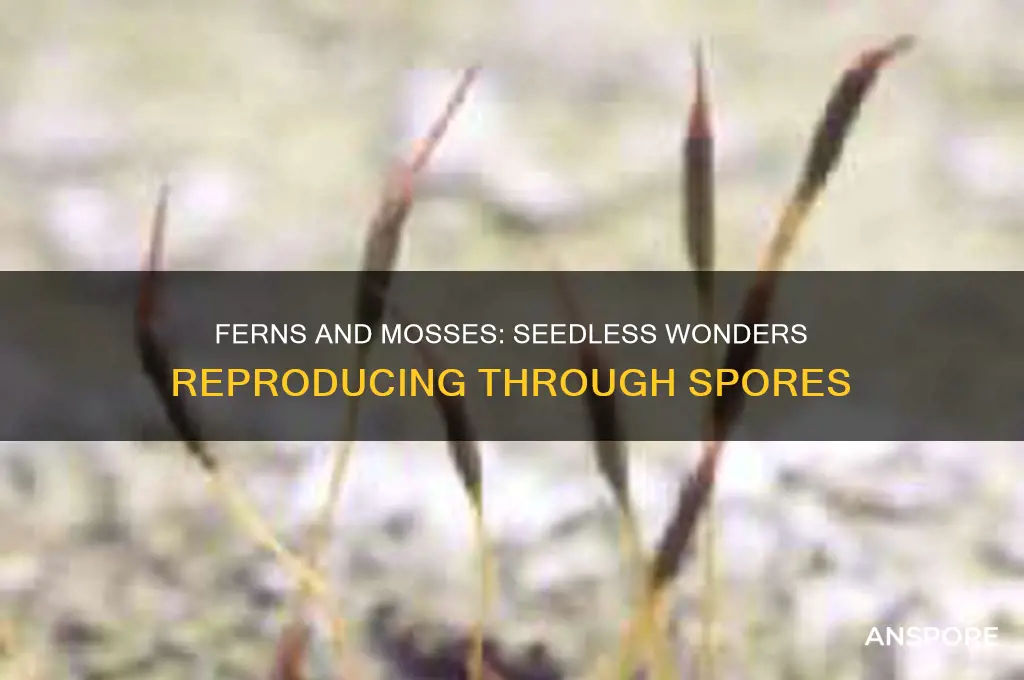

Ferns and mosses are both non-flowering plants that belong to the group of vascular and non-vascular plants, respectively, and their reproductive methods differ significantly from those of seed-bearing plants. Unlike flowering plants that reproduce through seeds, ferns and mosses rely on spores for reproduction, a process that is characteristic of plants in the early stages of evolution. Ferns produce spores on the undersides of their fronds, which, when released, can grow into small, heart-shaped structures called prothalli, where sexual reproduction occurs, ultimately leading to the development of new fern plants. Mosses, on the other hand, also reproduce via spores, which are produced in capsules at the tips of their stems and are dispersed to grow into new moss plants under suitable conditions. This spore-based reproductive strategy allows both ferns and mosses to thrive in diverse environments, from shady forests to rocky outcrops, without the need for seeds or flowers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Method | Ferns and mosses reproduce via spores, not seeds. |

| Type of Plant | Both are non-vascular plants (mosses) and vascular plants (ferns). |

| Spores vs. Seeds | Spores are haploid, single-celled structures; seeds are diploid, multicellular with stored food. |

| Life Cycle | Alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte phases). |

| Gametophyte Dominance | In mosses, the gametophyte is dominant; in ferns, the sporophyte is dominant. |

| Water Dependency for Reproduction | Both require water for sperm to swim to eggs during fertilization. |

| Habitat | Ferns and mosses thrive in moist, shaded environments. |

| Examples | Ferns: Bracken, Maidenhair; Mosses: Sphagnum, Sheet Moss. |

| Evolutionary Age | Mosses are older (evolved ~470 million years ago); ferns ~360 million years ago. |

| Seed-like Structures | Neither produces seeds; ferns have sporangia on the underside of leaves. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fern Reproduction Methods: Ferns reproduce via spores, not seeds, dispersed by wind or water

- Moss Reproduction Methods: Mosses also use spores, not seeds, for asexual and sexual reproduction

- Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are single-celled; seeds contain embryos with stored food

- Life Cycle of Ferns: Alternation of generations: sporophyte and gametophyte phases

- Life Cycle of Mosses: Dominant gametophyte phase; sporophyte depends on gametophyte

Fern Reproduction Methods: Ferns reproduce via spores, not seeds, dispersed by wind or water

Ferns, unlike flowering plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, they rely on spores as their primary method of reproduction. These microscopic, single-celled structures are produced in abundance on the undersides of fern fronds, in structures called sori. Each sorus contains hundreds to thousands of spores, ensuring a high probability of successful dispersal and germination. This spore-based reproductive strategy is a hallmark of ferns and is shared with other non-seed plants like mosses, though the specifics of their life cycles differ.

The dispersal of fern spores is a fascinating process, driven primarily by wind and water. Due to their lightweight nature, spores can travel significant distances when carried by air currents, allowing ferns to colonize new habitats efficiently. In moist environments, water can also play a role, transporting spores to suitable substrates where they can germinate. This dual dispersal mechanism highlights the adaptability of ferns to diverse ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands.

Once a spore lands in a favorable environment, it develops into a prothallus, a small, heart-shaped gametophyte. This stage of the fern life cycle is often overlooked but is crucial for reproduction. The prothallus produces both male and female reproductive cells. When water is present, sperm from the male organs swim to the female eggs, enabling fertilization. This dependence on water for fertilization is why ferns thrive in humid or wet conditions.

A key takeaway from fern reproduction is its alternation of generations, a unique feature of their life cycle. Ferns alternate between a spore-producing sporophyte (the plant we typically recognize as a fern) and a gamete-producing gametophyte (the prothallus). This complex cycle ensures genetic diversity and resilience, allowing ferns to survive in environments where seed-producing plants might struggle. Understanding this process not only sheds light on fern biology but also underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies in the plant kingdom.

For those interested in cultivating ferns, knowing their reproductive methods can be practical. Propagating ferns from spores requires patience and specific conditions. Spores should be sown on a sterile, moist medium, kept in a humid environment, and provided with indirect light. Germination can take several weeks, and the prothalli require consistent moisture to develop. While this method is more challenging than growing ferns from divisions, it offers a rewarding way to observe the entire fern life cycle firsthand.

Do Algae Reproduce by Spores? Unveiling Aquatic Plant Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Moss Reproduction Methods: Mosses also use spores, not seeds, for asexual and sexual reproduction

Mosses, unlike flowering plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, they rely on spores for both asexual and sexual reproduction, a method that has sustained these ancient plants for over 400 million years. This spore-based system is highly efficient in damp, shaded environments where mosses thrive, allowing them to disperse widely and colonize new habitats with minimal energy expenditure. Spores are lightweight, durable, and easily carried by wind or water, making them ideal for plants that lack roots, flowers, or fruits.

Sexual Reproduction in Mosses:

The sexual reproduction cycle of mosses involves two distinct generations: the gametophyte (the moss plant we typically see) and the sporophyte (a stalk-like structure that grows from the gametophyte). The gametophyte produces sex organs: antheridia (male) and archegonia (female). When water is present, sperm from the antheridia swim to the archegonia to fertilize the egg, forming a zygote. This zygote develops into the sporophyte, which eventually releases spores from a capsule at its tip. These spores germinate into new gametophytes, completing the cycle. This process is entirely dependent on moisture, highlighting mosses' adaptation to wet environments.

Asexual Reproduction via Spores:

While sexual reproduction ensures genetic diversity, mosses also reproduce asexually using spores. Spores produced by the sporophyte are haploid, meaning they contain a single set of chromosomes. When conditions are favorable, these spores grow directly into new gametophytes without fertilization. This method is rapid and efficient, allowing mosses to quickly colonize disturbed areas. Additionally, moss fragments can regenerate into new plants, a form of vegetative reproduction that complements spore-based methods.

Practical Tips for Observing Moss Reproduction:

To observe moss reproduction, collect a sample from a damp, shaded area and place it in a terrarium with consistent moisture. Monitor the plant for the development of sporophytes, which appear as small, stalk-like structures. Over time, you may notice spore capsules forming at the tips. For a closer look, use a magnifying glass or microscope to examine spores released from these capsules. To encourage asexual reproduction, gently break off small pieces of the moss and observe whether they grow into new plants.

Comparative Advantage of Spores Over Seeds:

Spores offer mosses a reproductive edge in their habitats. Unlike seeds, which require energy-intensive structures like flowers and fruits, spores are produced with minimal resource investment. Their small size and hard outer coating make them resilient to harsh conditions, ensuring survival during dispersal. This efficiency allows mosses to thrive in environments where seed-producing plants struggle, such as rocky outcrops, tree bark, and soil with low nutrient content. By mastering spore-based reproduction, mosses have become one of the most widespread plant groups on Earth.

Algae Reproduction: Unveiling the Role of Spores in Their Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Seeds: Spores are single-celled; seeds contain embryos with stored food

Ferns and mosses, unlike flowering plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, they rely on spores for reproduction, a method that has sustained these ancient lineages for millions of years. Spores are single-celled structures, lightweight and easily dispersed by wind or water, allowing these plants to colonize diverse environments. In contrast, seeds are multicellular, containing an embryo with stored food, which provides a head start for the developing plant. This fundamental difference in reproductive strategy highlights the evolutionary divergence between non-vascular (mosses) and vascular (ferns) plants and seed-bearing plants.

To understand the significance of spores, consider their role in the life cycle of ferns and mosses. After dispersal, a spore germinates into a gametophyte, a small, heart-shaped structure that produces sex cells. In ferns, this gametophyte is independent and photosynthetic, while in mosses, it remains dependent on the parent plant. Fertilization occurs when sperm from the male gametophyte swims to the egg on the female gametophyte, a process requiring water. The resulting zygote develops into a sporophyte, which produces new spores, completing the cycle. This reliance on water for reproduction is a key limitation, confining these plants to moist environments.

Seeds, on the other hand, offer a distinct advantage: they are self-contained survival kits. Encased in a protective coat, seeds contain an embryo, stored food (endosperm or cotyledons), and sometimes dormant hormones. This design allows seeds to withstand harsh conditions, such as drought or cold, and germinate when conditions improve. For example, a sunflower seed can remain viable in soil for years, waiting for the right combination of moisture and warmth. This adaptability has enabled seed plants to dominate terrestrial ecosystems, from forests to grasslands.

Practical observations of these reproductive strategies can be made in everyday settings. In a damp, shaded garden, you might notice ferns unfurling their fiddleheads or mosses carpeting the ground. These plants thrive where moisture is consistent, a requirement for spore-mediated reproduction. Conversely, in a dry, sunny meadow, seed-bearing plants like grasses and wildflowers dominate, their seeds dispersed by wind or animals. To encourage spore-reproducing plants, maintain soil moisture and avoid excessive sunlight. For seed-bearing plants, ensure proper spacing and provide nutrients to support seedling growth.

The contrast between spores and seeds underscores the diversity of plant reproductive strategies. Spores, with their simplicity and reliance on water, are a testament to the resilience of early plant forms. Seeds, with their complexity and self-sufficiency, represent an evolutionary leap that has shaped modern ecosystems. By observing these differences, we gain insight into the ecological niches these plants occupy and the conditions they require to thrive. Whether cultivating a garden or exploring the wild, understanding spores and seeds enhances our appreciation of the natural world.

Do Mushrooms Only Spore at Night? Unveiling Fungal Secrets

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle of Ferns: Alternation of generations: sporophyte and gametophyte phases

Ferns and mosses are prime examples of plants that reproduce via spores, not seeds, setting them apart from flowering plants. This distinction is rooted in their life cycles, which feature a unique process called alternation of generations. In ferns, this cycle involves two distinct phases: the sporophyte and the gametophyte, each with its own structure, function, and ecological role. Understanding this alternation is key to grasping how ferns propagate and thrive in diverse environments.

The sporophyte phase is the more visible stage of a fern’s life cycle, represented by the leafy, green plant we typically recognize. This phase is diploid, meaning its cells contain two sets of chromosomes. The sporophyte produces spores through structures called sporangia, often found on the undersides of mature fronds. When released, these spores are dispersed by wind or water, demonstrating the fern’s reliance on external factors for reproduction. Each spore is a single cell, lightweight and resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions until it lands in a suitable environment.

Transitioning to the gametophyte phase, the spore germinates into a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. This phase is haploid, with cells containing only one set of chromosomes. The prothallus is typically just a few millimeters in size and lives in moist, shaded areas. Its primary function is to produce gametes—sperm and eggs—through specialized structures. The sperm require water to swim to the egg, highlighting the fern’s dependence on moisture for successful reproduction. Once fertilization occurs, a new sporophyte develops, completing the cycle.

A critical takeaway from this alternation is the division of labor between the two phases. The sporophyte invests energy in growth and spore production, while the gametophyte focuses on sexual reproduction. This strategy ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, as spores can travel far from the parent plant, colonizing new habitats. For gardeners or enthusiasts cultivating ferns, maintaining consistent moisture and shade is essential to support both phases, particularly the water-dependent gametophyte.

In comparison to mosses, ferns share the trait of spore reproduction but differ in the dominance of their life cycle phases. In mosses, the gametophyte is the more prominent stage, while in ferns, the sporophyte takes center stage. This distinction underscores the evolutionary diversity within non-seed plants. By studying the alternation of generations in ferns, we gain insights into the intricate balance of nature and the strategies plants employ to survive and reproduce without seeds.

Circle of Spores Druids: Poison Immunity Explained in D&D 5e

You may want to see also

Life Cycle of Mosses: Dominant gametophyte phase; sporophyte depends on gametophyte

Mosses, unlike more complex plants, do not produce seeds. Instead, their life cycle revolves around spores, tiny, single-celled reproductive units that can disperse over long distances. This fundamental difference sets them apart from seed-bearing plants like ferns and flowering plants. The moss life cycle is characterized by a dominant gametophyte phase, a feature that highlights their evolutionary position as non-vascular plants.

The Gametophyte's Reign: Imagine a lush, green carpet of moss blanketing a forest floor. This verdant expanse is primarily composed of the gametophyte generation, the sexually reproducing phase of the moss life cycle. The gametophyte is a haploid organism, meaning it possesses a single set of chromosomes. It is the gametophyte that we typically recognize as "moss," with its leafy, photosynthetic body (thallus) and rhizoids anchoring it to the substrate. This phase is not only dominant in terms of visibility but also in terms of longevity. Moss gametophytes can survive for years, even decades, continuously growing and expanding through mitosis.

Sporophyte's Dependence: Emerging from the gametophyte are slender, stalk-like structures called sporophytes. These represent the diploid phase of the life cycle, carrying two sets of chromosomes. Unlike the independent gametophyte, the sporophyte is entirely dependent on its parent for water, nutrients, and physical support. It lacks the vascular tissue necessary for independent nutrient transport. At the tip of the sporophyte sits a capsule, where spores are produced through meiosis. This dependence on the gametophyte for survival is a key characteristic that distinguishes mosses from more advanced plants.

A Delicate Balance: The relationship between the gametophyte and sporophyte in mosses is a delicate one. The gametophyte provides the essential resources for the sporophyte's development, while the sporophyte ensures the production and dispersal of spores, guaranteeing the continuation of the species. This interdependence highlights the evolutionary strategy of mosses, prioritizing the longevity and resilience of the gametophyte while relying on the sporophyte for genetic diversity and dispersal. Understanding this unique life cycle is crucial for appreciating the adaptations that allow mosses to thrive in diverse environments, from damp forests to arid rock faces.

Do Spore Syringes Include Needles? Essential Tools Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ferns reproduce by spores, not seeds. They produce tiny, dust-like spores on the undersides of their fronds, which develop into new plants under suitable conditions.

Mosses reproduce by spores, not seeds. They release spores from capsule-like structures called sporangia, which grow into new moss plants when they land in a moist environment.

No, ferns and mosses are not seed-bearing plants. They are non-vascular (mosses) and vascular (ferns) plants that reproduce via spores, making them part of the group called "pteridophytes" and "bryophytes," respectively.

No, ferns and mosses cannot produce seeds. They rely on spores for reproduction, which is a primitive method compared to the seed-based reproduction of flowering plants and gymnosperms.