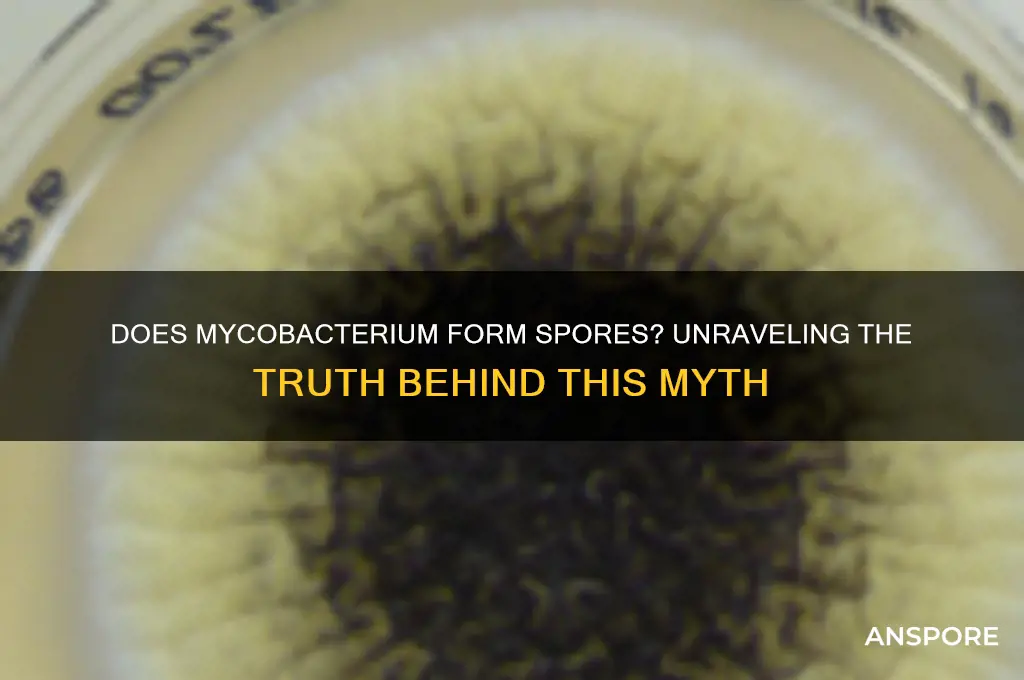

Mycobacterium, a genus of bacteria known for its unique cell wall composition and resistance to environmental stresses, is often associated with diseases such as tuberculosis and leprosy. One common question regarding these bacteria is whether they form spores, a survival mechanism employed by some microorganisms to endure harsh conditions. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Bacillus and Clostridium, mycobacteria do not produce spores. Instead, they rely on their robust cell wall, rich in mycolic acids, to withstand desiccation, disinfectants, and other adverse environments. This characteristic, combined with their slow growth rate, contributes to their persistence in clinical and environmental settings, making them a significant focus in microbiology and infectious disease research.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Does Mycobacterium form spores? | No |

| Reason | Mycobacteria lack the genetic and structural mechanisms required for sporulation, which are present in other bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium. |

| Survival Strategy | Mycobacteria survive harsh conditions through their waxy cell wall (rich in mycolic acids), which provides resistance to desiccation and disinfectants. |

| Dormancy | Some mycobacteria, like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, can enter a dormant, non-replicating state in response to stress, but this is not equivalent to spore formation. |

| Persistence | They can persist in hostile environments for extended periods due to their robust cell wall, but they do not produce spores for long-term survival. |

| Relevance | The absence of spore formation is a key distinction in their classification and behavior compared to spore-forming bacteria. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation in Mycobacteria: Mycobacteria do not form spores; they are non-spore-forming bacteria

- Survival Mechanisms: Mycobacteria survive via cell wall complexity, not spore formation

- Comparison with Spores: Unlike spore-formers (e.g., Bacillus), mycobacteria lack sporulation genes

- Environmental Persistence: Mycobacteria persist in harsh conditions without spore formation

- Clinical Implications: Non-spore-forming nature affects Mycobacterium tuberculosis treatment and disinfection strategies

Sporulation in Mycobacteria: Mycobacteria do not form spores; they are non-spore-forming bacteria

Mycobacteria, a genus of bacteria known for causing diseases like tuberculosis and leprosy, are often misunderstood when it comes to their survival mechanisms. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, mycobacteria do not produce spores. This distinction is critical in understanding their behavior in environments and their response to disinfection methods. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow some bacteria to survive extreme conditions, but mycobacteria rely on other strategies, such as forming biofilms or persisting within host cells, to endure harsh environments.

From a practical standpoint, the non-spore-forming nature of mycobacteria has significant implications for infection control. For instance, while spore-forming bacteria require specialized sterilization techniques like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, mycobacteria can typically be inactivated with less stringent methods. Standard disinfection protocols, such as using 70% ethanol or 0.5% sodium hypochlorite, are generally effective against mycobacteria. However, their waxy cell wall, rich in mycolic acids, provides inherent resistance to drying and some chemicals, necessitating thorough cleaning and contact times of at least 10 minutes for effective disinfection.

Comparatively, the absence of sporulation in mycobacteria highlights their evolutionary adaptation to specific niches. While spores enable bacteria to survive in diverse, often hostile environments, mycobacteria have evolved to thrive within host organisms, particularly macrophages. Their ability to evade the host immune system and persist in a dormant state, rather than forming spores, is a key factor in the chronic nature of diseases like tuberculosis. This distinction underscores why mycobacterial infections are notoriously difficult to treat, often requiring prolonged antibiotic regimens (e.g., 6–9 months for tuberculosis) to ensure complete eradication.

For laboratory workers and healthcare professionals, understanding that mycobacteria do not form spores is crucial for safety protocols. Unlike working with spore-formers, which may require biosafety level 3 (BSL-3) containment, most mycobacteria can be handled under BSL-2 conditions with proper precautions. However, aerosol-generating procedures, such as centrifugation or sonicating mycobacterial cultures, demand additional measures like HEPA filtration and personal protective equipment to prevent airborne transmission. This knowledge ensures efficient resource allocation and minimizes unnecessary over-containment.

In summary, the non-spore-forming nature of mycobacteria is a defining characteristic that shapes their ecology, pathogenicity, and management. While they lack the extreme resilience of spores, their unique cell wall and intracellular survival strategies pose distinct challenges. Recognizing this difference allows for targeted disinfection, appropriate laboratory handling, and effective treatment strategies, ultimately contributing to better control of mycobacterial infections.

Pollen Spores vs. Eggs: Unraveling the Botanical Mystery

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Mycobacteria survive via cell wall complexity, not spore formation

Mycobacteria, including the notorious *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, are masters of survival, but they achieve this without forming spores. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus anthracis* or *Clostridium botulinum*, which encapsulate their genetic material in a protective shell to endure harsh conditions, mycobacteria rely on a different strategy: their remarkably complex cell wall. This waxy, multilayered structure, rich in mycolic acids, acts as a formidable barrier against desiccation, antibiotics, and the host immune system. For instance, this cell wall composition allows *M. tuberculosis* to persist in macrophages, the very cells meant to destroy it, contributing to its ability to cause latent infections that can reactivate years later.

To understand the survival advantage of this cell wall, consider its role in antibiotic resistance. The lipid-rich outer layer slows the penetration of hydrophilic drugs, while the inner peptidoglycan layer provides structural integrity. This dual-layered defense mechanism explains why treating tuberculosis requires a prolonged regimen of multiple drugs, such as isoniazid, rifampicin, and ethambutol, often administered for 6–9 months. In contrast, spore-forming bacteria can survive extreme conditions like boiling or UV radiation but are generally more susceptible to antibiotics once their spores germinate. Mycobacteria, however, remain metabolically active yet protected, making them a unique challenge in clinical settings.

From a practical standpoint, the absence of spore formation in mycobacteria has significant implications for infection control. While spores can persist on surfaces for years, mycobacteria are less likely to survive outside a host for extended periods. For example, *M. tuberculosis* can remain viable in sputum or dust for weeks, but not decades like spores. This distinction informs disinfection protocols: standard hospital disinfectants like 70% ethanol or sodium hypochlorite are effective against mycobacteria, whereas spore-forming bacteria often require specialized sporicides. Healthcare workers should focus on respiratory precautions, such as N95 masks, to prevent airborne transmission rather than surface decontamination.

Comparatively, the survival mechanisms of mycobacteria and spore-forming bacteria highlight the diversity of microbial adaptation. While spores are a passive, dormant state, mycobacteria’s cell wall complexity allows them to actively resist environmental and host challenges. This distinction is crucial for researchers developing new treatments. Targeting mycolic acid synthesis, for instance, has led to drugs like ethionamide, which disrupt the cell wall and enhance antibiotic efficacy. Conversely, spore-targeted therapies focus on inhibiting germination or degrading the spore coat, a strategy irrelevant to mycobacteria. Understanding these differences ensures that interventions are tailored to the specific survival mechanisms of each pathogen.

In summary, mycobacteria’s survival hinges on their intricate cell wall, not spore formation. This adaptation enables them to withstand antibiotics, evade immune responses, and persist in hostile environments. For clinicians and researchers, this knowledge underscores the need for prolonged, multi-drug treatments and targeted therapies that exploit the cell wall’s vulnerabilities. Patients, particularly those in high-risk groups like immunocompromised individuals or those with HIV, should adhere strictly to prescribed regimens to prevent drug resistance. By focusing on the unique biology of mycobacteria, we can combat these resilient pathogens more effectively.

Do Actinobacteria Produce Spores? Unveiling Their Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Comparison with Spores: Unlike spore-formers (e.g., Bacillus), mycobacteria lack sporulation genes

Mycobacteria and spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus* share a reputation for resilience, but their survival strategies diverge fundamentally at the genetic level. While *Bacillus* species possess a well-defined set of sporulation genes that orchestrate the formation of highly resistant endospores, mycobacteria lack these genetic blueprints entirely. This absence explains why mycobacteria, despite their hardiness, do not produce spores. Instead, they rely on a thick, waxy cell wall composed of mycolic acids to withstand harsh conditions, a mechanism distinct from sporulation.

To understand the implications, consider the survival of *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* in dry sputum for weeks or even months. This longevity is not due to spore formation but rather to the protective lipid barrier that shields the bacterium from desiccation and environmental stressors. In contrast, *Bacillus anthracis* forms spores that can persist in soil for decades, a capability directly tied to its sporulation genes. This comparison highlights the evolutionary trade-offs: mycobacteria invest in a robust cell wall, while spore-formers allocate resources to a more energy-intensive but highly effective sporulation process.

From a practical standpoint, this genetic difference has significant implications for disinfection and sterilization. Spores of *Bacillus* require extreme measures, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, to ensure inactivation. Mycobacteria, however, are generally susceptible to less intense methods, like exposure to 70% ethanol or boiling water for 30 minutes, due to their non-spore-forming nature. Understanding this distinction is crucial for healthcare settings, where mycobacterial contamination poses a risk but can be managed with standard disinfection protocols.

Finally, the absence of sporulation genes in mycobacteria offers a unique lens for studying bacterial survival strategies. Researchers can explore how mycobacteria’s waxy cell wall evolved as an alternative to sporulation, shedding light on adaptive mechanisms in pathogenic bacteria. For instance, the development of drugs targeting mycolic acid synthesis, such as isoniazid for tuberculosis, leverages this structural vulnerability. In contrast, spore-formers present a different challenge, requiring strategies to disrupt their highly resistant spore coats. This comparative analysis underscores the importance of genetic differences in shaping bacterial survival and informing targeted interventions.

Are Spore-Printed Mushroom Caps Safe to Eat? A Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$27.25

Environmental Persistence: Mycobacteria persist in harsh conditions without spore formation

Mycobacteria, unlike spore-forming bacteria such as *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*, do not produce spores as a survival mechanism. Yet, they exhibit remarkable environmental persistence, thriving in conditions that would eliminate many other microorganisms. This ability is rooted in their unique cell wall composition, which is rich in mycolic acids—long, hydrophobic fatty acids that form a waxy barrier. This impermeable layer protects against desiccation, extreme temperatures, and disinfectants, allowing mycobacteria to survive in soil, water, and even household surfaces for months to years. For instance, *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* can persist in dust for up to six months, while *Mycobacterium avium* complex (MAC) remains viable in tap water for over a year.

Understanding this persistence is critical for infection control, particularly in healthcare settings. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which require specialized sterilization techniques like autoclaving at 121°C, mycobacteria can often withstand routine disinfection methods. For example, ethanol-based hand sanitizers (effective against most pathogens) are less reliable against mycobacteria due to their waxy cell wall. Instead, disinfectants containing chlorine (e.g., 5,000 ppm available chlorine) or hydrogen peroxide (e.g., 6% solution) are recommended for surface decontamination. In clinical laboratories, mycobacteria are handled under Biosafety Level 2 or 3 conditions, depending on the species, to prevent aerosolization and transmission.

Comparatively, the persistence of mycobacteria without spore formation highlights their evolutionary adaptation to harsh environments. While spores are a dormant, highly resistant form, mycobacteria remain metabolically active, albeit at a reduced rate, in adverse conditions. This metabolic flexibility allows them to utilize limited nutrients and repair cellular damage over time. For example, *Mycobacterium smegmatis* can survive in nutrient-poor soil by entering a slow-growing state, reactivating when conditions improve. This contrasts with spore-formers, which remain dormant until triggered to germinate by specific environmental cues.

Practically, this persistence has implications for water treatment and food safety. Mycobacteria can colonize biofilms in water distribution systems, resisting chlorine disinfection commonly used in municipal water treatment. To mitigate this, additional filtration (e.g., 0.2-micron filters) or UV treatment is recommended. In food processing, mycobacteria can survive pasteurization temperatures (72°C for 15 seconds), necessitating more stringent heat treatments or alternative methods like high-pressure processing. For individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS or undergoing chemotherapy, avoiding untreated water and thoroughly cooking food is essential to prevent opportunistic infections like MAC or *Mycobacterium abscessus*.

In summary, mycobacteria’s environmental persistence without spore formation is a testament to their robust cellular architecture and metabolic adaptability. This trait poses unique challenges in infection control, water treatment, and food safety, requiring targeted strategies beyond those effective against spore-forming bacteria. By understanding these mechanisms, we can develop more effective interventions to limit their spread and protect public health.

How Spores Shield Pathogenic Bacteria from Extreme Temperature Stress

You may want to see also

Clinical Implications: Non-spore-forming nature affects Mycobacterium tuberculosis treatment and disinfection strategies

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), does not form spores, a characteristic that significantly influences its clinical management. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which can survive harsh conditions by entering a dormant, highly resistant state, M. tuberculosis relies on its robust cell wall for survival. This non-spore-forming nature has profound implications for both treatment and disinfection strategies, shaping how healthcare providers approach TB control.

From a treatment perspective, the absence of spores means M. tuberculosis does not exhibit the same level of resistance to environmental stressors as spore-forming pathogens. However, its waxy cell wall, rich in mycolic acids, provides inherent protection against many antibiotics and disinfectants. This necessitates the use of combination therapy, typically involving drugs like isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, to prevent the emergence of drug-resistant strains. For instance, the standard first-line treatment for drug-sensitive TB is a six-month regimen, with an initial intensive phase of two months followed by a continuation phase of four months. Adherence to this regimen is critical, as incomplete treatment can lead to relapse or the development of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB), which requires longer, more toxic, and costlier treatment options.

In disinfection strategies, the non-spore-forming nature of M. tuberculosis simplifies certain aspects of infection control compared to spore-forming bacteria like Clostridium difficile. M. tuberculosis is susceptible to common disinfectants such as bleach (sodium hypochlorite) and ultraviolet (UV) light, which are effective in decontaminating surfaces and air in healthcare settings. For example, a 1:10 dilution of household bleach (5,000 ppm) is recommended for disinfecting surfaces potentially contaminated with M. tuberculosis. However, its ability to survive in a dry state for weeks necessitates rigorous environmental control measures, particularly in high-risk areas like TB wards and laboratories. HEPA filtration and negative-pressure ventilation systems are essential in preventing airborne transmission, as M. tuberculosis is primarily spread through respiratory droplets.

The non-spore-forming nature of M. tuberculosis also impacts patient isolation protocols. Unlike spore-forming pathogens, which can persist in the environment for extended periods, M. tuberculosis requires immediate attention to airborne transmission risks. Patients with active pulmonary TB should be placed in respiratory isolation until they are no longer infectious, typically after two weeks of effective treatment. This highlights the importance of rapid diagnosis and initiation of therapy, as early intervention reduces the risk of transmission and improves treatment outcomes.

In summary, the non-spore-forming nature of M. tuberculosis dictates specific treatment and disinfection strategies. While it eliminates the need to address spore-related resistance, it demands targeted approaches to overcome its unique cell wall defenses and prevent transmission. Clinicians and infection control specialists must remain vigilant in adhering to evidence-based protocols, ensuring effective management of TB in both individual patients and community settings.

Endospore-Forming Organisms: Dangerous Pathogens or Harmless Survivors?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Mycobacterium does not form spores. Unlike some bacteria, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, Mycobacterium lacks the ability to produce endospores.

Mycobacterium survives through its robust cell wall, which is rich in mycolic acids, providing resistance to desiccation, disinfectants, and environmental stresses.

No, none of the Mycobacterium species are known to form spore-like structures. Their survival mechanisms rely on their unique cell wall composition and ability to persist in hostile environments.

Understanding that Mycobacterium does not form spores is crucial for developing effective disinfection and sterilization methods, as spore-targeting strategies are not applicable to these bacteria.

![Substances screened for ability to reduce thermal resistance of bacterial spores 1959 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Z99EgARVL._AC_UL320_.jpg)