Staphylococcus epidermidis, a Gram-positive bacterium commonly found on human skin, is known for its role as a commensal organism and occasional opportunistic pathogen. Unlike some other bacterial species, such as Bacillus and Clostridium, S. epidermidis does not form spores under normal conditions. Sporulation is a survival mechanism employed by certain bacteria to withstand harsh environments, but S. epidermidis relies instead on its ability to form biofilms and adapt to diverse conditions without transitioning into a spore state. This characteristic is crucial for understanding its behavior in clinical settings, where it often causes biofilm-associated infections on medical devices.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Natural Habitat of S. epidermidis

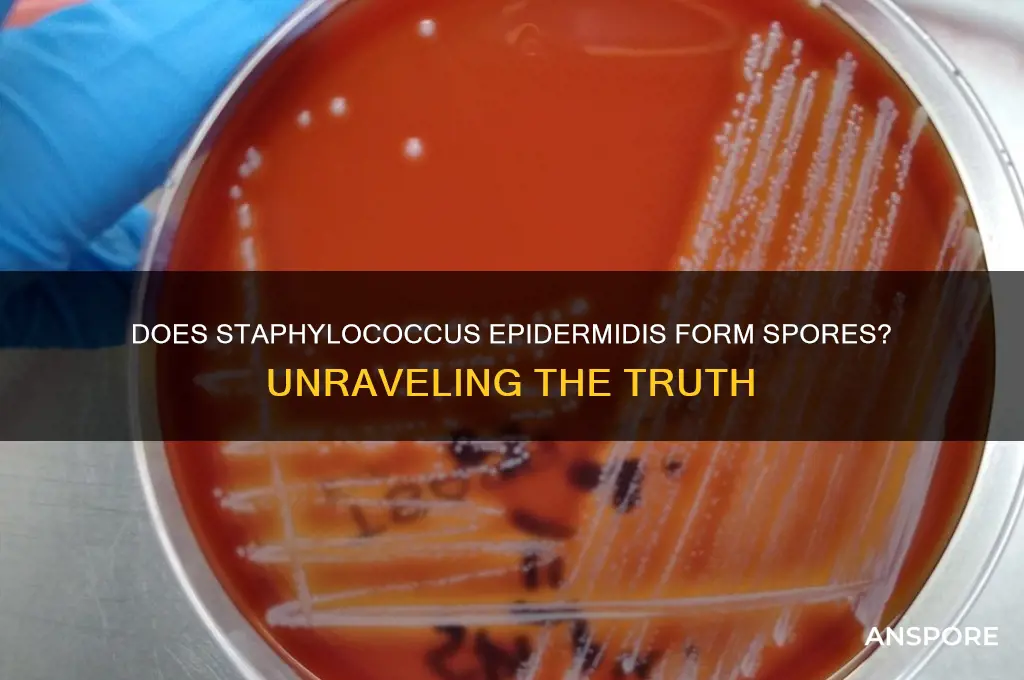

Staphylococcus epidermidis is a gram-positive, coagulase-negative bacterium that primarily colonizes the human skin and mucous membranes. Unlike its more notorious relative, Staphylococcus aureus, S. epidermidis is generally considered a commensal organism, meaning it exists harmoniously with its host under normal conditions. Its natural habitat is the outermost layer of the skin, where it thrives in the slightly oily and moist environment provided by sebaceous glands. This bacterium is particularly fond of areas rich in sebum, such as the face, scalp, and upper back, where it forms part of the skin’s natural microbiota. Understanding its habitat is crucial because it influences the bacterium’s behavior, including its ability—or lack thereof—to form spores.

Analyzing the environmental preferences of S. epidermidis reveals why it does not form spores. Sporulation is a survival mechanism employed by certain bacteria to endure harsh conditions, such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient deprivation. However, S. epidermidis has evolved to flourish in the stable, nutrient-rich environment of human skin, where such stressors are minimal. Its metabolic adaptability allows it to utilize skin-derived nutrients like fatty acids and amino acids efficiently, eliminating the need for spore formation. This contrasts with spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus anthracis, which inhabit unpredictable environments and require dormancy to survive.

From a practical standpoint, knowing the natural habitat of S. epidermidis helps in managing its role in healthcare settings. While it is typically harmless, it can become an opportunistic pathogen, particularly in immunocompromised individuals or those with indwelling medical devices. For instance, S. epidermidis is a leading cause of catheter-related bloodstream infections. To mitigate this risk, healthcare providers should focus on maintaining skin integrity and using antiseptic solutions like chlorhexidine (2% concentration) for skin preparation before procedures. Additionally, regular hand hygiene with alcohol-based rubs (at least 60% alcohol) can reduce its transmission in clinical environments.

Comparatively, the habitat of S. epidermidis also highlights its ecological niche within the human microbiome. Unlike transient skin flora, which are frequently acquired from the environment, S. epidermidis is a permanent resident, adhering strongly to skin surfaces through biofilm formation. This biofilm acts as a protective matrix, enhancing its survival and resistance to antimicrobials. While spore formation is not part of its survival strategy, biofilm production serves a similar purpose by shielding the bacterium from external threats. This distinction underscores the importance of targeting biofilms in infection control, rather than focusing on spore eradication.

In conclusion, the natural habitat of S. epidermidis on human skin explains its lack of spore formation. Its adaptation to a stable, nutrient-rich environment negates the need for such a survival mechanism. For healthcare professionals and individuals alike, this knowledge emphasizes the importance of skin hygiene and biofilm disruption in preventing S. epidermidis-related infections. By focusing on its unique ecological niche, we can develop more effective strategies to manage this bacterium in both commensal and pathogenic contexts.

Do Fungi Produce Spores? Unveiling Their Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process in Bacteria

Staphylococcus epidermidis, a common commensal bacterium found on human skin, does not form spores. This characteristic distinguishes it from other bacteria like Clostridium and Bacillus, which are known for their ability to sporulate under adverse conditions. Sporulation is a complex, highly regulated process that allows certain bacteria to survive extreme environments, such as high temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient deprivation. Understanding this process is crucial for grasping why some bacteria endure while others perish under similar conditions.

The sporulation process in bacteria involves a series of morphological and biochemical changes that culminate in the formation of a highly resistant spore. It begins with an asymmetric cell division, where the bacterium divides into a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, providing a protective environment for its maturation. During this phase, the forespore synthesizes a thick, multilayered coat composed of proteins and peptidoglycan, which confers resistance to heat, chemicals, and enzymes. This coat is essential for the spore’s ability to withstand harsh conditions, making it a key focus in studying bacterial survival mechanisms.

One of the most fascinating aspects of sporulation is its genetic regulation. The process is controlled by a cascade of transcription factors, primarily Spo0A, which activates genes involved in spore formation. This regulatory network ensures that sporulation occurs only when environmental conditions signal the need for survival. For example, Bacillus subtilis initiates sporulation in response to nutrient depletion, a process that takes approximately 8 hours under laboratory conditions. In contrast, Staphylococcus epidermidis lacks the genetic machinery for sporulation, relying instead on biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance mechanisms for survival.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporulation has significant implications for infection control and food safety. Spores of bacteria like Clostridium botulinum can survive boiling temperatures, making them a concern in canned foods. To ensure safety, commercial canning processes often involve heating food to 121°C for at least 3 minutes, a condition known as the "botulinum cook." Conversely, the non-sporulating nature of Staphylococcus epidermidis means that standard hygiene practices, such as handwashing and surface disinfection, are typically sufficient to control its spread.

In conclusion, while Staphylococcus epidermidis does not form spores, the sporulation process in other bacteria provides valuable insights into microbial survival strategies. By studying this process, researchers can develop more effective methods for controlling pathogenic bacteria and ensuring public health. Whether in a laboratory or a food processing plant, understanding sporulation is a critical tool in the fight against bacterial persistence.

Understanding Spores: Their Role, Survival Mechanisms, and Ecological Impact

You may want to see also

S. epidermidis Survival Mechanisms

Staphylococcus epidermidis, a common commensal bacterium found on human skin, does not form spores. This characteristic distinguishes it from other spore-forming pathogens like Clostridium difficile, which can survive harsh conditions through sporulation. However, S. epidermidis has evolved a suite of survival mechanisms that enable it to persist in diverse environments, including hospital settings where it often causes opportunistic infections. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing effective strategies to control its spread and treat associated infections.

One of S. epidermidis's most notable survival strategies is its ability to form biofilms, a structured community of bacteria encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix. Biofilms provide a protective barrier against antibiotics, host immune responses, and environmental stressors such as desiccation. For instance, in medical device-related infections, S. epidermidis readily colonizes surfaces like catheters and prosthetics, forming biofilms that are up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than planktonic cells. To mitigate this, healthcare providers often use antimicrobial coatings on devices or administer high-dose antibiotic lock therapy (e.g., 10 mg/mL vancomycin in catheter locks) to disrupt biofilm formation.

Another key survival mechanism is S. epidermidis's ability to adapt metabolically to nutrient-limited environments. Unlike spore-forming bacteria, which enter a dormant state, S. epidermidis slows its metabolic activity while remaining viable. This is achieved through the production of small colony variants (SCVs), which are slow-growing phenotypic variants that arise under stress conditions. SCVs are particularly problematic in chronic infections, as they evade detection by standard diagnostic methods and exhibit increased resistance to antibiotics like aminoglycosides. Clinicians often need to extend treatment durations (e.g., 6–8 weeks of rifampin and fusidic acid) to effectively target SCVs.

S. epidermidis also exploits its host environment by modulating the immune response. It produces surface proteins like polysaccharide intercellular adhesin (PIA) and teichoic acids that interfere with phagocytosis and complement activation. Additionally, it secretes enzymes such as proteases and lipases that degrade host tissues and nutrients, facilitating colonization. This immune evasion is particularly critical in immunocompromised patients, where S. epidermidis can cause severe infections despite its generally low virulence. Prophylactic measures, such as topical antiseptics (e.g., 2% chlorhexidine gluconate) and strict aseptic techniques during medical procedures, are essential to prevent colonization in vulnerable populations.

Comparatively, while S. epidermidis lacks the extreme resilience of spore-forming bacteria, its survival mechanisms are highly effective in clinical contexts. Its ability to form biofilms, adapt metabolically, and evade the immune system underscores the need for targeted interventions. For example, combining antibiotics with biofilm-disrupting agents like DNase or dispersin B can enhance treatment efficacy. Similarly, early detection of SCVs through molecular techniques (e.g., PCR for hemB mutations) can guide appropriate therapy. By addressing these mechanisms, healthcare professionals can better manage S. epidermidis infections and reduce the risk of recurrence.

Algae Reproduction: Unveiling the Role of Spores in Their Life Cycle

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Comparison with Spore-Forming Bacteria

Staphylococcus epidermidis, a common commensal bacterium found on human skin, does not form spores. This characteristic sets it apart from spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* or *Clostridium botulinum*, which produce highly resistant spores as a survival mechanism. Understanding this distinction is crucial for infection control, treatment strategies, and laboratory practices.

Analytically, the absence of spore formation in *S. epidermidis* means it is more susceptible to standard disinfection methods, such as alcohol-based sanitizers (e.g., 70% isopropyl alcohol) and heat treatment (e.g., autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes). In contrast, spore-forming bacteria require more aggressive measures, like prolonged exposure to high temperatures (e.g., 134°C for 3 hours) or specialized chemical agents (e.g., hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid), to ensure eradication. This difference highlights the importance of identifying the bacterial species in clinical and industrial settings to apply appropriate decontamination protocols.

Instructively, healthcare professionals should note that *S. epidermidis* is primarily a concern in immunocompromised patients or those with indwelling medical devices, where it can form biofilms. While it lacks spores, its biofilm-forming ability provides a level of environmental persistence. To mitigate this, regular cleaning of medical equipment with 2% chlorhexidine or 10% povidone-iodine is recommended. For spore-forming bacteria, however, biofilm disruption alone is insufficient; spore-specific sterilization techniques must be employed to prevent outbreaks, such as in food processing plants where *Clostridium* spores can survive standard cleaning procedures.

Persuasively, the non-spore-forming nature of *S. epidermidis* should not lead to complacency. While it is less resilient than spore-forming bacteria, its ability to colonize medical devices and cause opportunistic infections underscores the need for vigilant hygiene practices. For instance, hand hygiene with alcohol-based rubs for at least 20–30 seconds is effective against *S. epidermidis* but would be inadequate for spores. This comparison emphasizes the importance of tailoring infection control measures to the specific bacterial threat.

Comparatively, the survival strategies of *S. epidermidis* and spore-forming bacteria illustrate the diversity of microbial adaptation. While *S. epidermidis* relies on biofilm formation and rapid proliferation in nutrient-rich environments, spore-forming bacteria invest energy in producing dormant, stress-resistant spores. This divergence in survival mechanisms explains why *S. epidermidis* is more commonly associated with hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) in healthcare settings, whereas spore-formers are often linked to foodborne illnesses or environmental contamination. Recognizing these differences enables targeted interventions, such as using antimicrobial coatings on catheters to prevent *S. epidermidis* biofilms or implementing spore-specific decontamination in food production facilities.

Does Salmonella Enterica Form Spores? Unraveling the Bacterial Mystery

You may want to see also

Clinical Implications of Non-Sporulation

Staphylococcus epidermidis, a common commensal bacterium of human skin, does not form spores. This characteristic significantly influences its clinical behavior and management in healthcare settings. Unlike spore-forming bacteria such as Clostridium difficile, S. epidermidis lacks the ability to survive in harsh conditions by entering a dormant, resilient state. This non-sporulating nature has both advantages and challenges in clinical practice, particularly in infection control and treatment strategies.

From an infection control perspective, the non-sporulation of S. epidermidis simplifies disinfection protocols. Standard hospital disinfectants, such as 70% isopropyl alcohol or quaternary ammonium compounds, effectively eliminate vegetative cells of S. epidermidis from surfaces and medical devices. Unlike spores, which require specialized sporicidal agents like hydrogen peroxide vapor or peracetic acid, routine cleaning measures suffice. For example, in central line maintenance, healthcare providers can rely on alcohol-based scrubs to reduce S. epidermidis colonization on insertion sites, minimizing catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSIs). However, this reliance on standard disinfection must be paired with vigilance, as S. epidermidis is adept at forming biofilms on indwelling devices, which can protect the bacteria from biocides and host defenses.

Clinically, the non-sporulating nature of S. epidermidis impacts antibiotic treatment strategies. Since spores are not a concern, therapy focuses on eradicating actively growing cells. For systemic infections, such as prosthetic joint infections or endocarditis, combination therapy with rifampin and glycopeptides (e.g., vancomycin) is often employed to target biofilm-embedded bacteria. Dosage adjustments are critical; for instance, rifampin is typically administered at 300 mg every 8 hours in adults, while vancomycin dosing is weight-based (15–20 mg/kg every 8–12 hours) with therapeutic drug monitoring to maintain trough levels of 15–20 μg/mL. In pediatric populations, dosing is age- and weight-specific, requiring careful calculation to avoid toxicity. The absence of spores simplifies treatment but demands aggressive biofilm management, often necessitating device removal in severe cases.

The non-sporulation of S. epidermidis also has implications for diagnostic workflows. Since spores are not produced, laboratory identification relies on detecting active growth or genetic material. Blood cultures, for example, may take 24–48 hours to yield positive results, during which empiric therapy must be initiated based on clinical suspicion. Rapid molecular diagnostics, such as PCR-based assays, are increasingly used to identify S. epidermidis in biofilms, guiding targeted therapy. However, the lack of spore-specific markers simplifies the diagnostic process compared to spore-forming pathogens, where additional tests (e.g., spore staining) might be required.

In summary, the non-sporulation of S. epidermidis shapes clinical practice by streamlining disinfection protocols, focusing antibiotic therapy on active cells, and simplifying diagnostics. While this characteristic reduces the need for sporicidal measures, it underscores the importance of biofilm management and device-related infection prevention. Healthcare providers must remain vigilant, employing evidence-based strategies to combat this persistent pathogen in both acute and chronic infections.

Can Spore Run Smoothly on Windows 7? Compatibility Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, Staphylococcus epidermidis does not form spores. It is a non-spore-forming bacterium.

Staphylococcus epidermidis lacks the genetic and metabolic mechanisms required for spore formation, which is a characteristic of certain other bacteria like Bacillus and Clostridium.

Yes, Staphylococcus epidermidis can survive in harsh conditions through other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation and resistance to desiccation, but it does not rely on spore formation.

No, none of the staphylococcal species, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, are known to form spores. They are all non-spore-forming bacteria.