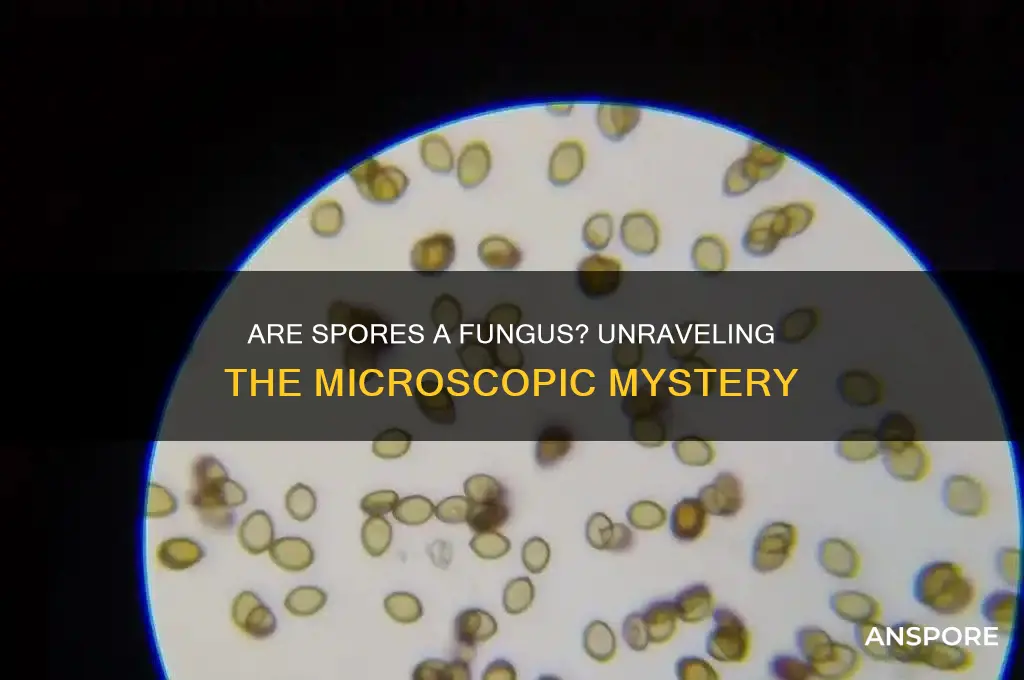

Spores are often associated with fungi, but understanding whether they are inherently a fungus requires a closer look at their biological role and structure. Spores are reproductive units produced by various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria, serving as a means of dispersal and survival in adverse conditions. In the case of fungi, spores are a critical part of their life cycle, allowing them to spread and colonize new environments. However, not all spores are fungal; for instance, plant spores, such as those from ferns or mosses, are distinct from fungal spores in both function and morphology. Therefore, while spores are a defining feature of fungi, they are not exclusive to them, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between different types of spores based on their origin and characteristics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spores Definition | Spores are reproductive units produced by fungi, plants, algae, and some bacteria. They are typically single-celled and can develop into a new organism under favorable conditions. |

| Fungal Spores | Fungal spores are specifically produced by fungi as part of their life cycle. They are a means of reproduction and dispersal. |

| Fungus Definition | A fungus is a member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. Fungi are classified as a separate kingdom, distinct from plants and animals. |

| Relationship | Fungal spores are a part of the fungal life cycle, but not all spores are fungal. Spores can be produced by various organisms, including plants (e.g., pollen, seeds) and bacteria (e.g., endospores). |

| Fungal Spore Types | Fungi produce various types of spores, including: 1. Sporangiospores: produced inside a sporangium (e.g., Zygomycota). 2. Conidiospores: produced at the ends of specialized hyphae called conidiophores (e.g., Aspergillus). 3. Ascospores: produced inside a sac-like structure called an ascus (e.g., Saccharomyces). 4. Basidiospores: produced on a club-shaped structure called a basidium (e.g., mushrooms). |

| Fungal Spore Function | Fungal spores serve as a means of: 1. Reproduction: allowing fungi to produce new individuals. 2. Dispersal: enabling fungi to spread to new environments. 3. Survival: helping fungi withstand harsh conditions (e.g., drought, extreme temperatures). |

| Non-Fungal Spores | Examples of non-fungal spores include: 1. Plant spores: produced by ferns, mosses, and other non-seed plants. 2. Bacterial endospores: produced by certain bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) as a survival mechanism. |

| Key Distinction | While fungal spores are a type of spore, not all spores are fungal. The term "spore" is broader and encompasses reproductive units from multiple kingdoms of life. |

Explore related products

$23.29 $24.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Definition: Spores are reproductive units, not fungi themselves, but produced by some fungi

- Fungal Spores: Fungi release spores for reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions

- Spore vs. Fungus: Spores are parts of fungi, not independent organisms; fungi are the whole

- Non-Fungal Spores: Plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and bacteria also produce spores, not just fungi

- Spore Function: Spores aid in fungal colonization, longevity, and adaptation to diverse environments

Spore Definition: Spores are reproductive units, not fungi themselves, but produced by some fungi

Spores are often mistaken for fungi, but this confusion stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of their role. While it’s true that certain fungi produce spores, these microscopic structures are not fungi themselves. Instead, spores function as reproductive units, akin to seeds in plants, designed to disperse and propagate the fungal species under favorable conditions. This distinction is crucial for anyone studying microbiology, gardening, or even home mold remediation, as it clarifies the lifecycle and behavior of fungi.

To illustrate, consider the common black mold (*Stachybotrys chartarum*), which releases spores into the air as part of its reproductive process. These spores are lightweight and can travel long distances, settling in damp environments where they germinate into new fungal colonies. However, the spores themselves are not mold—they are the means by which mold reproduces. This is why spore counts are often measured in air quality assessments; high levels indicate a potential mold problem, but the spores are merely the messengers, not the mold itself.

From a practical standpoint, understanding this difference is essential for effective mold control. For instance, wiping down surfaces with a damp cloth may remove visible mold but can inadvertently spread spores, exacerbating the issue. Instead, use a HEPA-filtered vacuum or a solution of bleach and water (1 cup bleach per gallon of water) to kill spores and prevent regrowth. Always wear protective gear, such as gloves and an N95 mask, when handling moldy materials to avoid inhaling spores, which can trigger allergies or respiratory issues in sensitive individuals.

Comparatively, spores share similarities with other reproductive structures in nature, like pollen or bacterial endospores, but their function is uniquely tied to fungi and certain plants (e.g., ferns and mosses). Unlike pollen, which relies on external agents like wind or insects for dispersal, fungal spores are self-sufficient, capable of surviving harsh conditions until they find a suitable environment to grow. This resilience makes them both a marvel of biology and a challenge for those seeking to control fungal growth in homes or gardens.

In conclusion, while spores are intimately associated with fungi, they are not fungi themselves but rather the reproductive tools fungi use to ensure their survival and spread. Recognizing this distinction allows for more informed and effective strategies in managing fungal growth, whether in a laboratory, home, or natural setting. By treating spores as what they are—dispersal units, not the organism itself—you can better target interventions and prevent unnecessary confusion or missteps in fungal control efforts.

Mycotoxins vs. Spores: Understanding the Key Differences and Risks

You may want to see also

Fungal Spores: Fungi release spores for reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions

Fungi are masters of survival, and their secret weapon is the spore. These microscopic structures are not fungi themselves but rather specialized cells produced by fungi for specific purposes. Think of them as tiny, durable capsules containing the genetic material needed to start a new fungal organism.

Fungal spores serve three crucial functions: reproduction, dispersal, and survival.

Reproduction: Unlike animals that rely on mating for reproduction, most fungi reproduce asexually through spore formation. A single fungus can produce millions of spores, ensuring the continuation of its genetic lineage. This asexual reproduction allows for rapid population growth under favorable conditions.

For example, the common bread mold *Aspergillus* releases spores that, when landing on a suitable food source like stale bread, germinate and grow into new mold colonies.

Dispersal: Spores are incredibly lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or tails, allowing them to be carried by wind, water, or even insects over vast distances. This dispersal mechanism is vital for fungi to colonize new habitats and exploit diverse resources. Imagine a puffball fungus releasing a cloud of spores that travel on the breeze, eventually landing on a decaying log miles away, where they can establish a new fungal community.

Survival in Harsh Conditions: Spores are remarkably resilient. They can withstand extreme temperatures, dryness, and even radiation. This dormancy allows fungi to survive unfavorable conditions like winter or drought. When conditions improve, spores germinate and resume growth. Consider the spores of certain yeast species that can survive for years in a dry state, only to spring back to life when rehydrated.

Understanding fungal spores is crucial in various fields. In agriculture, managing spore dispersal can help control plant diseases caused by fungi. In medicine, studying spore resistance aids in developing antifungal treatments. By appreciating the remarkable adaptability of fungal spores, we gain valuable insights into the fascinating world of fungi and their impact on our lives.

Best Time to Apply Milky Spore for Grub Control in Lawns

You may want to see also

Spore vs. Fungus: Spores are parts of fungi, not independent organisms; fungi are the whole

Spores are often mistaken for independent organisms, but they are, in fact, reproductive units produced by fungi, much like seeds in plants. This misunderstanding arises because spores can survive harsh conditions and travel long distances, giving the impression of autonomy. However, they are fundamentally parts of a larger fungal organism, incapable of independent growth or metabolism. Fungi, on the other hand, are complex, multicellular structures that include mycelium, fruiting bodies, and spores. Understanding this relationship is crucial for fields like mycology, agriculture, and medicine, where distinguishing between the part (spore) and the whole (fungus) is essential for accurate identification and treatment.

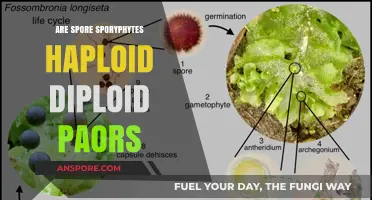

To illustrate, consider the lifecycle of a mushroom. The mushroom itself is a fruiting body, a visible structure that emerges from an extensive underground network of mycelium. Spores are produced within the mushroom’s gills or pores and are released into the environment to disperse and germinate under favorable conditions. Without the mycelium, spores cannot develop into new fungi. Conversely, the mycelium relies on spores for reproduction and colonization of new habitats. This interdependence highlights that spores are not standalone entities but specialized components of the fungal organism.

From a practical standpoint, this distinction has significant implications. For instance, in fungal infections, antifungal treatments target the mycelium or the fungal cell wall, not the spores directly. Spores are often more resistant to treatment due to their dormant state and protective coatings. In agriculture, understanding spore dispersal helps in managing fungal diseases, such as powdery mildew or rust, by implementing strategies like crop rotation or fungicide application at critical spore release periods. Recognizing spores as parts of fungi, not independent invaders, refines these approaches for greater effectiveness.

A comparative analysis further clarifies the spore-fungus relationship. While spores are akin to plant seeds, fungi are more analogous to the entire plant, including roots, stems, and flowers. Just as a seed cannot perform photosynthesis or grow without the support of the plant’s root system, a spore cannot metabolize or reproduce without the fungal mycelium. This analogy underscores the spore’s role as a reproductive tool rather than an independent life form. It also emphasizes the importance of studying fungi as integrated organisms, rather than focusing solely on their dispersive elements.

In conclusion, the misconception that spores are independent fungi stems from their remarkable resilience and dispersal capabilities. However, they are intrinsically tied to the fungal organism, functioning as reproductive units rather than autonomous entities. By grasping this distinction, professionals and enthusiasts alike can better navigate the complexities of fungal biology, from disease management to ecological roles. Spores are not the fungus—they are a vital part of it, contributing to the organism’s survival and propagation in diverse environments.

Are Mildew Spores Dangerous? Understanding Health Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Non-Fungal Spores: Plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and bacteria also produce spores, not just fungi

Spores are often mistakenly associated exclusively with fungi, but this is a narrow view of their biological role. While fungal spores are well-known for their ability to disperse and colonize new environments, they are far from the only organisms to employ this reproductive strategy. Plants, particularly ferns and mosses, also produce spores as part of their life cycle. For instance, ferns release tiny, dust-like spores from the undersides of their fronds, which can travel great distances on air currents before germinating under suitable conditions. This method of reproduction allows these plants to thrive in diverse habitats, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands.

Bacteria, too, produce spores, though these are structurally and functionally distinct from both fungal and plant spores. Bacterial spores, such as those formed by *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, are highly resistant to extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and desiccation. This resilience makes them a significant concern in food safety and sterilization processes. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores can survive in improperly canned foods, posing a risk of botulism if the spores germinate and produce toxin. Understanding the differences between bacterial spores and those of fungi or plants is crucial for effective control measures, such as using autoclaves at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure spore destruction.

The production of spores in non-fungal organisms highlights their evolutionary significance as a survival mechanism. In plants like mosses, spores enable colonization of barren or disturbed environments, as they require minimal resources to germinate and grow. This adaptability is particularly evident in bryophytes, which often dominate early stages of ecological succession. Similarly, bacterial spores serve as a dormant form, allowing microorganisms to endure harsh conditions until favorable circumstances return. This contrasts with fungal spores, which are primarily dispersal agents rather than survival structures, though some fungi, like *Aspergillus*, can also form resistant structures called sclerotia.

Practical applications of non-fungal spores extend beyond biology into horticulture and industry. For gardeners, understanding fern and moss spore germination can enhance propagation efforts. Fern spores, for instance, require a sterile, moist medium and indirect light to develop into prothalli, the initial stage of their life cycle. In contrast, moss spores thrive on damp, nutrient-poor substrates, making them ideal for green roofs or soil stabilization projects. Meanwhile, industries must account for bacterial spores in sterilization protocols, particularly in pharmaceuticals and food production, where spore contamination can have severe consequences.

In summary, while spores are commonly linked to fungi, their presence in plants and bacteria underscores their versatility as a reproductive and survival strategy. From the delicate spores of ferns to the resilient endospores of bacteria, these structures play critical roles in the persistence and dispersal of diverse organisms. Recognizing this broader context not only deepens our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications in fields ranging from ecology to public health. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or factory, the impact of non-fungal spores is both profound and far-reaching.

Are Spore Growths on Potatoes Safe to Eat?

You may want to see also

Spore Function: Spores aid in fungal colonization, longevity, and adaptation to diverse environments

Spores are not fungi themselves but rather microscopic, resilient structures produced by fungi (and some plants, bacteria, and algae) to ensure survival and dispersal. Think of them as fungal "seeds," designed to endure harsh conditions until they find a suitable environment to germinate and grow. This distinction is crucial: while spores are integral to fungal life cycles, they are not living organisms in the same sense as the fungi that produce them. Instead, they serve as vehicles for fungal colonization, longevity, and adaptation across diverse environments.

Consider the process of spore dispersal, a marvel of natural engineering. Fungi release spores in staggering quantities—a single mushroom can emit billions in a day. These spores are lightweight and often equipped with structures like wings or tails, allowing them to travel vast distances via wind, water, or even animal carriers. For example, the spores of *Aspergillus* fungi, commonly found in soil and decaying matter, can survive extreme temperatures and humidity levels, enabling them to colonize environments from Arctic tundra to tropical rainforests. This adaptability is not just a survival mechanism but a strategic advantage, ensuring fungi can thrive in niches where other organisms cannot.

Longevity is another critical function of spores. In dormant states, spores can remain viable for decades, even centuries, waiting for optimal conditions to activate. This is particularly evident in species like *Cladosporium*, whose spores can persist in soil or on surfaces until moisture and nutrients become available. Such resilience allows fungi to outlast environmental stressors, from droughts to wildfires, ensuring their continued presence in ecosystems. For instance, spores of the fungus *Neurospora crassa* have been revived from 20-million-year-old amber, demonstrating their extraordinary capacity for long-term survival.

Adaptation is where spores truly shine. Each spore carries genetic material that can mutate or recombine during germination, enabling fungi to evolve rapidly in response to environmental pressures. This is especially vital in pathogenic fungi like *Candida albicans*, which uses spores to adapt to host immune systems and antifungal treatments. For practical purposes, understanding spore adaptation is key in agriculture and medicine. Farmers can rotate crops to disrupt spore cycles, while clinicians can prescribe antifungal medications like fluconazole (typically 150–300 mg daily for adults) to target spore-forming fungi, though caution is advised due to rising resistance.

In essence, spores are not just passive agents but active contributors to fungal success. Their role in colonization, longevity, and adaptation underscores their significance in both natural and human-altered environments. Whether you’re a gardener battling powdery mildew or a researcher studying fungal ecology, recognizing the function of spores provides actionable insights. For instance, reducing humidity levels below 60% can inhibit spore germination in indoor spaces, while using fungicides with spore-specific targets can enhance crop protection. By leveraging this knowledge, we can better manage fungal interactions and harness their benefits while mitigating their drawbacks.

Do Mold Spores Fluctuate with Seasons? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are not a fungus themselves but are reproductive structures produced by fungi (and some other organisms) to propagate and survive in various environments.

Yes, all fungi produce spores as part of their life cycle, though the type and method of spore production vary among different fungal species.

Yes, under suitable conditions, spores can germinate and grow into new fungal organisms, continuing the life cycle of the fungus.

No, spores are the reproductive units of fungi, while mold refers to the visible growth of fungal colonies, often consisting of many spores and other fungal structures.