Spore stains are a valuable diagnostic tool in microbiology, offering a simple yet effective method to visualize and identify bacterial spores. This staining technique is particularly useful for distinguishing between spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria, which is crucial in various fields such as medicine, food safety, and environmental monitoring. By applying specific dyes and heat, spore stains allow microbiologists to observe the unique characteristics of spores, including their resistance to staining and their distinct morphology. This process aids in the rapid identification of potentially harmful spore-forming pathogens, such as *Clostridium* and *Bacillus* species, enabling timely interventions and appropriate treatment strategies. Furthermore, spore stains play a significant role in research, helping scientists study spore formation, germination, and the mechanisms behind spore resistance, ultimately contributing to advancements in microbiology and related disciplines.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Identification of Bacterial Spores | Spore stains differentiate spore-forming bacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Clostridium) from non-spore-forming bacteria, aiding in species identification. |

| Resistance Assessment | Spores are highly resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation. Spore stains help evaluate their resistance properties, crucial for sterilization studies. |

| Environmental Monitoring | Used to detect spore-forming bacteria in environmental samples (e.g., soil, water), ensuring safety in healthcare, food, and pharmaceutical industries. |

| Clinical Diagnostics | Helps diagnose infections caused by spore-forming pathogens, such as Clostridium difficile or Bacillus anthracis. |

| Quality Control | Ensures effectiveness of sterilization processes (e.g., autoclaving) by confirming spore inactivation in medical equipment and supplies. |

| Research Applications | Studies spore morphology, germination, and viability under various conditions, advancing microbiology research. |

| Differential Staining | Uses dyes (e.g., malachite green, safranin) to distinguish spores (green) from vegetative cells (red), providing clear visualization under microscopy. |

| Rapid Results | Quick staining process (typically 30–60 minutes) allows for timely identification and decision-making in clinical and industrial settings. |

| Cost-Effective | Relatively inexpensive compared to molecular methods, making it accessible for routine laboratory use. |

| Historical Significance | A traditional microbiological technique still widely used due to its reliability and simplicity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying bacterial spore presence

Bacterial spores are highly resistant structures that can survive extreme conditions, making their detection crucial in various fields, from medicine to environmental science. Spore stains are a fundamental technique in microbiology, offering a simple yet powerful method to identify these resilient forms. This process involves a series of steps that differentiate spores from vegetative bacterial cells, providing valuable insights into the presence and characteristics of spore-forming bacteria.

The Art of Spore Staining:

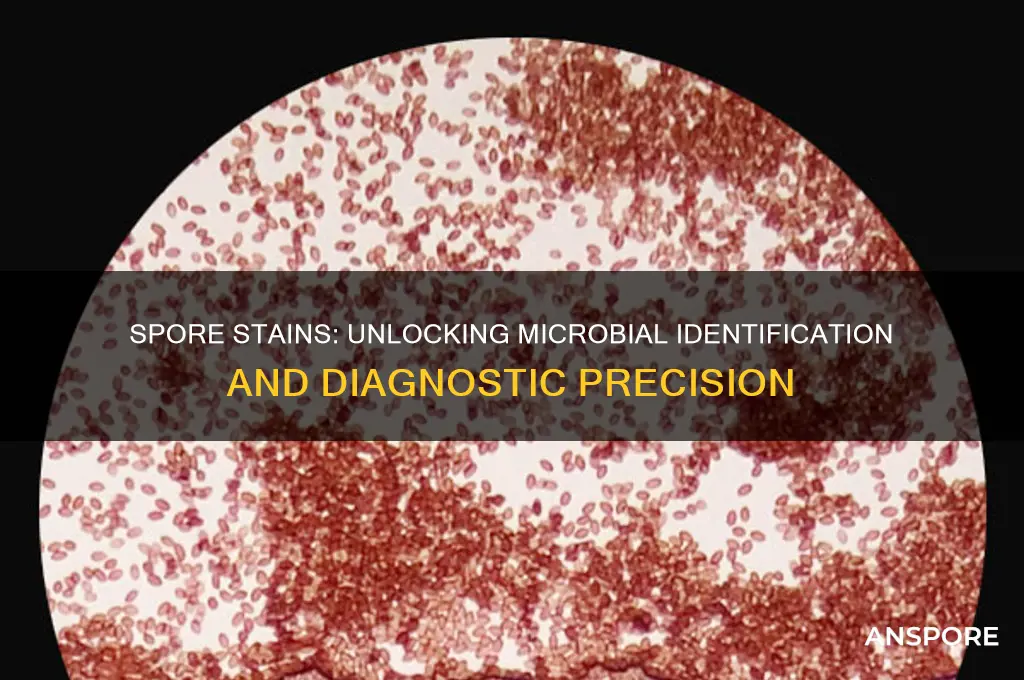

Imagine a scenario where a microbiologist is tasked with identifying a potential spore-forming pathogen in a clinical sample. The first step is to prepare a smear of the bacterial culture on a microscope slide. Here's where the magic begins. The staining procedure typically employs a combination of dyes, such as malachite green and safranin, which differentially stain spores and vegetative cells. Malachite green, a primary stain, penetrates the spore's impermeable coat, while safranin, a counterstain, colors the vegetative cells and background. After staining, the slide is examined under a microscope, revealing distinct green-colored spores against a pink or red background. This visual contrast is key to identification.

Unveiling the Spore's Secrets:

The beauty of spore staining lies in its ability to provide rapid and specific results. When examining the stained slide, one can observe the size, shape, and arrangement of spores, which are often unique to specific bacterial species. For instance, *Bacillus* spores are typically oval and located centrally or subterminally in the cell, while *Clostridium* spores are larger and more swollen. This morphological analysis is a critical step in preliminary identification. Furthermore, the stain's intensity and the spore's resistance to decolorization during the process offer additional clues about the spore's maturity and viability.

Practical Applications and Considerations:

In a clinical setting, spore staining is invaluable for quickly identifying potential pathogens like *Clostridium difficile* or *Bacillus anthracis*. For instance, in a patient with suspected anthrax, a spore stain can provide rapid confirmation, guiding immediate treatment decisions. However, it's essential to note that spore staining is not without limitations. The technique may not distinguish between viable and non-viable spores, and some bacteria may require specific staining modifications for optimal results. Therefore, it is often used in conjunction with other tests for comprehensive identification.

Mastering the Technique:

To ensure accurate results, technicians must adhere to precise staining protocols. This includes controlling the heating duration during the malachite green application, as overheating can kill spores and affect staining. Additionally, the choice of decolorizer is critical; water is typically used, but for more resistant spores, a weaker acid may be necessary. Proper slide preparation and staining technique are paramount to avoid false negatives or positives. With practice, microbiologists can master this art, contributing to efficient and effective bacterial identification.

In summary, spore staining is a powerful tool for identifying bacterial spores, offering rapid visual identification and morphological analysis. Its applications span clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and research, providing a simple yet elegant solution to a complex problem. By understanding the intricacies of this technique, microbiologists can unlock valuable information about spore-forming bacteria, contributing to better-informed decisions in various fields.

Can Dogs Safely Eat Mushroom Spores? Risks and Facts Revealed

You may want to see also

Differentiating spore-forming bacteria

Spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, present unique challenges in identification due to their resilient endospores. Spore stains, particularly the Schaeffer-Fulton method, are indispensable for differentiating these organisms from non-spore formers. This technique employs a combination of heat, primary stains (e.g., malachite green), and counterstains (e.g., safranin) to highlight spores as refractile, green bodies against a pink cellular background. The presence, size, location (terminal, central, or subterminal), and shape (oval, spherical, or swollen) of spores provide critical morphological clues for species-level identification.

Consider the following scenario: a clinical sample yields Gram-positive, rod-shaped bacteria. Without spore staining, distinguishing between *Bacillus anthracis* (causative agent of anthrax) and *Lactobacillus* (a non-pathogenic commensal) would be impossible based on Gram stain alone. Spore staining reveals *B. anthracis*’s characteristic large, central spores, enabling rapid identification and appropriate treatment initiation. This example underscores the diagnostic precision spore stains afford in clinical microbiology.

To perform a spore stain effectively, follow these steps: heat-fix the smear, apply malachite green for 5 minutes (with gentle heat to enhance penetration), rinse thoroughly, decolorize with water, counterstain with safranin for 1 minute, and examine under oil immersion (1000x magnification). Caution: overheating during staining can distort spore morphology, while inadequate decolorization may obscure results. For optimal results, use fresh reagents and standardize heating protocols (e.g., 80°C water bath for malachite green application).

Comparatively, alternative methods like the Dorner method (using picric acid as a decolorizer) or the Moeller method (employing carbol fuchsin) offer variations in staining intensity and spore contrast. However, the Schaeffer-Fulton method remains the gold standard for its simplicity, reliability, and compatibility with most spore-forming bacteria. Its ability to preserve cellular morphology while distinctly marking spores makes it invaluable for both research and clinical settings.

In conclusion, spore stains are not merely a laboratory exercise but a critical tool for differentiating spore-forming bacteria with precision. By revealing spore characteristics, they bridge the gap between ambiguous Gram stain results and definitive identification. Mastery of this technique empowers microbiologists to diagnose infections accurately, study spore biology, and implement targeted interventions, particularly in cases of bioterrorism or foodborne outbreaks.

Should You Download All Spore DLC? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Assessing spore viability

Spore viability assessment is a critical step in determining the effectiveness of sterilization processes, particularly in medical, pharmaceutical, and food industries. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are highly resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation, making them a significant challenge to eradicate. Therefore, verifying whether spores have been successfully inactivated is essential to ensure safety and compliance with regulatory standards.

One widely used method for assessing spore viability is the spore stain technique, which involves differential staining to distinguish between viable and non-viable spores. For instance, the malachite green staining method is commonly employed. In this process, spores are heated to allow the malachite green dye to penetrate the spore coat. Subsequently, a counterstain such as safranin is applied to differentiate between spores and background debris. Viable spores retain the green color, while non-viable spores appear pink or colorless. This method is particularly useful for its simplicity and cost-effectiveness, though it requires careful control of heating time and temperature to avoid false results.

Another advanced approach is the use of fluorescent dyes in conjunction with spore stains. For example, the combination of propidium iodide (PI) and SYTO 9 in the LIVE/DEAD spore viability kit allows for rapid assessment under a fluorescence microscope. PI penetrates damaged spore membranes, staining non-viable spores red, while SYTO 9 stains all spores green. The viability is then determined by the ratio of green to red fluorescence. This method offers higher sensitivity and faster results compared to traditional staining, making it ideal for high-throughput applications.

When assessing spore viability, it’s crucial to consider the limitations of each method. For instance, some spores may enter a viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, where they remain alive but cannot be detected by traditional culturing techniques. Additionally, over-heating during staining can lead to false-positive results by damaging viable spores. To mitigate these risks, always follow manufacturer guidelines for reagent concentrations and incubation times. For example, when using malachite green, heat spores at 80°C for 30 minutes, and for fluorescent dyes, ensure the dye concentration does not exceed 10 μM to avoid toxicity effects.

In practical applications, spore viability assessment is often integrated into validation protocols for autoclaves, dry heat sterilizers, and chemical disinfectants. For instance, in pharmaceutical manufacturing, Bacillus atrophaeus spores are commonly used as biological indicators to test sterilization cycles. By comparing the viability of spores before and after sterilization, operators can confirm the process’s efficacy. Regular monitoring and documentation of these tests are essential to meet regulatory requirements, such as those outlined in USP <1227> or ISO 11138 standards.

In conclusion, assessing spore viability through staining techniques is a cornerstone of sterilization validation. Whether using traditional methods like malachite green or advanced fluorescent dyes, the key lies in precise execution and understanding the method’s limitations. By incorporating these techniques into routine testing, industries can ensure the reliability of their sterilization processes, safeguarding both product quality and public health.

Can Shroomish Learn Stun Spore? Exploring Moveset Possibilities

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Studying spore morphology

Spore morphology—the study of spore structure and form—is a cornerstone of microbiology, offering insights into identification, function, and ecological roles. By examining size, shape, color, and surface features, researchers can differentiate between species, predict environmental adaptations, and assess potential health risks. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores are larger and more polygonal than those of *Bacillus cereus*, a distinction critical in diagnostic settings. This morphological analysis, often enhanced by spore stains, provides a visual fingerprint that complements molecular techniques.

To study spore morphology effectively, begin with proper staining techniques. The Schaeffer-Fulton stain, a differential method, highlights spores in green against red vegetative cells, making them easily distinguishable under a light microscope. For more detailed analysis, phase-contrast or scanning electron microscopy (SEM) can reveal intricate surface structures like exosporium layers or spore coat textures. When preparing samples, ensure spores are in their mature, dormant state, as immature spores may lack defining features. Use a 1:10 dilution of the spore suspension to avoid overcrowding on the slide, which can obscure individual structures.

Comparative analysis of spore morphology across species reveals evolutionary adaptations. For example, the smooth, thick-walled spores of *Clostridium botulinum* reflect their need to survive harsh conditions, while the rough, filamentous spores of *Streptomyces* species facilitate attachment to surfaces. Such comparisons not only aid in taxonomic classification but also inform applications in biotechnology. Spores with robust coats, like those of *Bacillus subtilis*, are studied for their potential in drug delivery systems due to their stability and resistance to degradation.

Practical tips for studying spore morphology include maintaining consistent staining protocols to ensure reproducibility. Use a standardized microscope calibration slide to accurately measure spore dimensions, typically ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 micrometers in diameter. For advanced users, software tools like ImageJ can analyze spore images for precise measurements and surface area calculations. When working with pathogenic spores, such as those of *Anthrax*, adhere to biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) practices, including the use of a biological safety cabinet and proper personal protective equipment.

In conclusion, studying spore morphology through staining and microscopy is a powerful tool for identification, research, and applied science. By mastering techniques, understanding adaptations, and applying practical tips, researchers can unlock the secrets of these resilient structures. Whether for diagnostic purposes, ecological studies, or biotechnological advancements, spore morphology remains an indispensable area of study in microbiology.

Mold Spores: Do They Die or Continue to Spread?

You may want to see also

Evaluating disinfection effectiveness

Spore stains are indispensable in evaluating disinfection effectiveness, particularly in healthcare and laboratory settings where microbial control is critical. By targeting endospores—the most resilient form of bacterial life—these stains provide a definitive measure of a disinfectant’s ability to eliminate the hardiest pathogens. Unlike vegetative cells, endospores can survive extreme conditions, including heat, chemicals, and radiation, making them the gold standard for assessing disinfection efficacy. A successful disinfection process should not only kill vegetative bacteria but also destroy these dormant, protective forms.

To evaluate disinfection effectiveness using spore stains, follow a structured protocol. First, prepare a spore suspension of a known concentration, typically using *Bacillus subtilis* or *Bacillus atrophaeus*, which are standard test organisms. Apply the disinfectant at the recommended dosage—for example, a 1:10 dilution of bleach (5,000–8,000 ppm chlorine) for surface disinfection—and ensure contact time aligns with manufacturer guidelines, often 10–30 minutes. After exposure, neutralize the disinfectant to halt its activity, then plate the treated suspension onto nutrient agar. Incubate at 37°C for 24–48 hours. If no colonies grow, the disinfectant has effectively inactivated the spores, indicating robust efficacy.

A critical caution in this process is avoiding false negatives. Inadequate neutralization of the disinfectant can inhibit spore germination, leading to misleading results. Use a neutralizer specific to the disinfectant—for instance, sodium thiosulfate for chlorine-based agents—and verify its effectiveness through control tests. Additionally, ensure the spore suspension is uniformly distributed during testing to prevent clustering, which can skew results. Practical tips include using sterile techniques to avoid contamination and confirming spore viability before testing to ensure accurate baseline data.

Comparatively, spore stains offer a more rigorous assessment than traditional methods like phenol coefficient tests, which focus on vegetative bacteria. While these tests are useful for general disinfection, they fall short in high-risk environments like hospitals or pharmaceutical cleanrooms, where spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* pose significant threats. Spore stains bridge this gap, providing a definitive measure of a disinfectant’s ability to ensure sterility. For instance, in a study comparing disinfectants in a hospital ICU, only those that passed spore stain tests were deemed suitable for preventing healthcare-associated infections.

In conclusion, spore stains are a cornerstone in evaluating disinfection effectiveness, offering a reliable, standardized method to validate microbial control. By targeting the most resistant bacterial forms, they ensure disinfectants meet the highest safety standards. Whether in healthcare, food processing, or research, incorporating spore stains into disinfection protocols provides actionable data to optimize practices and safeguard public health. Their specificity and rigor make them an essential tool for anyone serious about microbial eradication.

Alcohol vs. Mildew: Can It Effectively Kill Spores?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A spore stain is a specialized staining technique used to differentiate bacterial spores from vegetative cells. It typically involves the use of heat (heat fixation) and specific dyes like malachite green, followed by a counterstain such as safranin. Spores retain the primary stain due to their impermeable structure, appearing green, while vegetative cells take up the counterstain, appearing red or pink.

Spore stains are useful for identifying spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species. They help distinguish between spore-forming and non-spore-forming bacteria, which is critical for diagnosis, classification, and understanding bacterial survival mechanisms in harsh environments.

Spore stains are valuable in food microbiology to detect spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium botulinum* or *Bacillus cereus*, in clinical settings to identify spore-forming infections, and in environmental studies to assess bacterial resilience. They are also essential in quality control for sterilization processes, as spores are highly resistant to heat and chemicals.