Spores and sperm are both reproductive structures, but they serve distinct purposes and exhibit significant differences. Spores are typically produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria as a means of asexual reproduction or dispersal, allowing them to survive harsh conditions and colonize new environments. They are often resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemicals, enabling long-term dormancy. In contrast, sperm are male reproductive cells found in animals and some plants, specifically designed for sexual reproduction. Sperm are motile, equipped with a tail (flagellum) to swim toward the female egg, and carry half the genetic material necessary for fertilization. While spores focus on survival and propagation, sperm are specialized for the immediate goal of combining genetic material to create offspring, highlighting their fundamentally different roles in the reproductive strategies of organisms.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Type of Organism | Spores: Produced by plants, fungi, algae, and some bacteria. Sperm: Produced by animals and some plants (e.g., gymnosperms). |

| Function | Spores: Primarily for asexual reproduction, dispersal, and survival in harsh conditions. Sperm: Solely for sexual reproduction, requiring fusion with an egg (female gamete). |

| Mobility | Spores: Generally non-motile, relying on wind, water, or other external means for dispersal. Sperm: Motile, equipped with a flagellum or tail for active movement toward the egg. |

| Structure | Spores: Typically single-celled, thick-walled, and resistant to environmental stress. Sperm: Single-celled, with a streamlined structure optimized for movement (e.g., head, midpiece, and tail). |

| Genetic Material | Spores: Contain a haploid or diploid nucleus, depending on the life cycle stage. Sperm: Always haploid, carrying half the genetic material of the parent. |

| Size | Spores: Generally larger and more robust, designed for durability. Sperm: Smaller and more lightweight, optimized for mobility. |

| Lifespan | Spores: Can remain dormant for extended periods (years to centuries) in harsh conditions. Sperm: Short-lived, typically surviving only a few hours to days. |

| Production Location | Spores: Produced in specialized structures (e.g., sporangia in fungi, cones in plants). Sperm: Produced in reproductive organs (e.g., testes in animals, pollen grains in plants). |

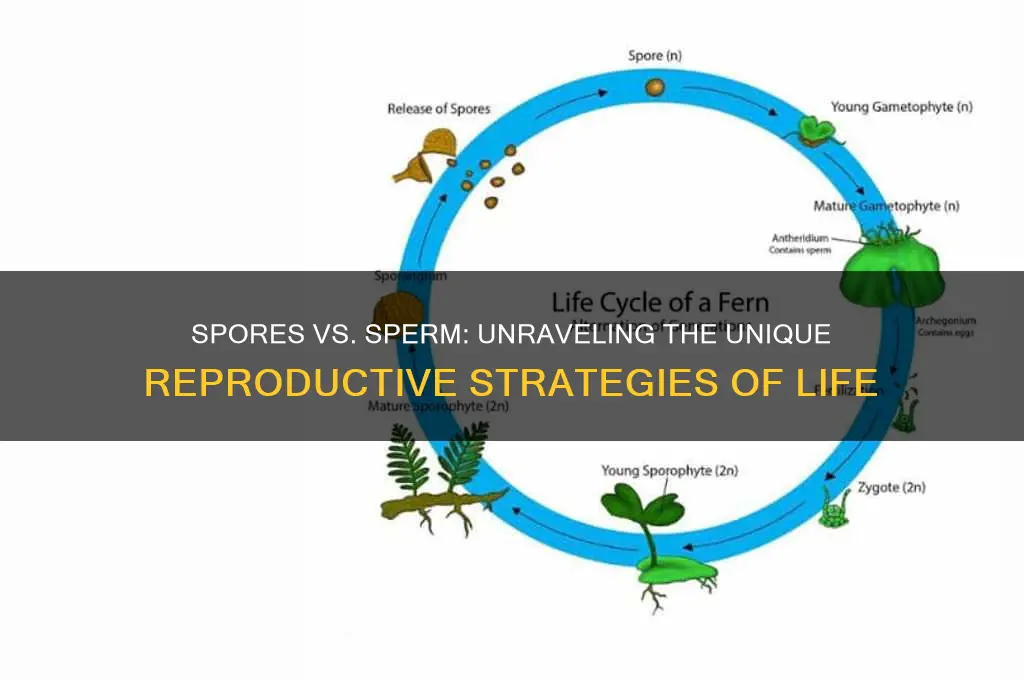

| Role in Life Cycle | Spores: Often part of alternation of generations (e.g., in ferns and mosses). Sperm: Part of the sexual reproductive phase in organisms with gametic reproduction. |

| Environmental Resistance | Spores: Highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals, aiding survival. Sperm: Fragile, requiring a suitable environment (e.g., water or mucus) for viability. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Size and Structure: Spores are larger, single-celled, and self-sustaining; sperm are small, motile, and specialized

- Function: Spores reproduce asexually and survive harsh conditions; sperm fertilize eggs for sexual reproduction

- Motility: Sperm are actively motile with tails; spores are passive and dispersed by wind/water

- Genetic Material: Spores contain full genetic sets for independent life; sperm carry half the genetic material

- Lifespan: Spores can remain dormant for years; sperm have a short lifespan, often hours or days

Size and Structure: Spores are larger, single-celled, and self-sustaining; sperm are small, motile, and specialized

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, diverge dramatically in size and structure, reflecting their distinct roles and environments. Spores, often larger than sperm, are single-celled entities designed for survival in harsh conditions. For instance, fungal spores can range from 1 to 100 micrometers in diameter, while bacterial endospores are typically 0.5 to 1.5 micrometers. This size allows them to store nutrients and protective layers, enabling them to endure extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation. In contrast, sperm cells are minuscule, measuring around 50 micrometers in length, with a streamlined structure optimized for motility. This size difference underscores their functions: spores are built for resilience, while sperm are engineered for mobility and efficiency in reaching an egg.

Consider the structural adaptations that accompany these size differences. Spores are self-sustaining, encased in a tough outer wall that shields their genetic material. This wall, composed of materials like chitin in fungi or peptidoglycan in bacteria, acts as a barrier against environmental stressors. Sperm, however, are specialized for a single purpose: fertilization. Their structure is minimalistic, featuring a compact head containing DNA, a midpiece packed with mitochondria for energy, and a tail (flagellum) for propulsion. This specialization sacrifices durability for speed and agility, a trade-off that aligns with their immediate reproductive goal.

To illustrate, imagine a spore as a well-equipped survivalist and a sperm as a sprinting athlete. The spore’s larger size and robust structure allow it to lie dormant for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. For example, *Bacillus* spores can survive boiling water and remain viable for decades. Conversely, sperm have a short lifespan, typically surviving only a few days outside the body, and require a fluid medium to swim. Their motility is powered by ATP from mitochondria, enabling them to navigate through reproductive tracts. This comparison highlights how size and structure directly correlate with function: spores prioritize longevity, while sperm prioritize rapid movement.

Practical implications of these differences are evident in fields like agriculture and medicine. Farmers use spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus thuringiensis*, as biopesticides because of their resilience and ability to persist in soil. In contrast, fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF) rely on the motility and viability of sperm, often selecting the most active and structurally intact cells for insemination. Understanding these structural distinctions can guide strategies for preservation, propagation, and manipulation of these reproductive units in various applications.

In summary, the size and structure of spores and sperm are finely tuned to their ecological and biological roles. Spores’ larger, self-sustaining design equips them for survival, while sperm’s small, motile, and specialized structure enables efficient fertilization. These differences are not arbitrary but are evolutionary adaptations that ensure the continuity of species in diverse environments. By examining these traits, we gain insights into the ingenious ways life perpetuates itself, whether through endurance or swift action.

Can Spores Develop into Independent Individuals? Exploring the Science

You may want to see also

Function: Spores reproduce asexually and survive harsh conditions; sperm fertilize eggs for sexual reproduction

Spores and sperm serve fundamentally different roles in the reproductive strategies of organisms, each adapted to distinct environmental and biological pressures. Spores are the resilient, asexually reproducing units of plants, fungi, and some microorganisms. Their primary function is to endure harsh conditions—extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient scarcity—by entering a dormant state. This survival mechanism allows them to persist for years, even decades, until conditions improve. For example, bacterial endospores can withstand boiling water, radiation, and chemicals, making them nearly indestructible. In contrast, sperm are specialized cells in animals and some plants designed for a single, time-sensitive purpose: fertilizing eggs to initiate sexual reproduction. Their function is not survival but mobility and genetic diversity, achieved through the fusion of gametes.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern versus a human to illustrate these differences. Ferns release spores that disperse via wind, landing in various environments. Those that find suitable conditions germinate into gametophytes, which produce eggs and sperm. The sperm require water to swim to the egg, highlighting their fragility and dependence on immediate conditions. Humans, on the other hand, produce sperm in vast quantities—up to 1,500 per second in a healthy adult male—to increase the likelihood of successful fertilization. Unlike spores, sperm cannot survive outside the reproductive tract for more than a few hours, emphasizing their specialized, transient role.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these differences has significant implications in fields like agriculture, medicine, and conservation. Farmers use spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus thuringiensis*, as natural pesticides because of their durability and ability to persist in soil. In contrast, fertility treatments like in vitro fertilization (IVF) rely on the precise handling and viability of sperm, often requiring controlled environments to mimic the reproductive tract. For instance, sperm used in IVF are typically washed and concentrated to improve motility, a process that underscores their fragility compared to spores.

The contrasting functions of spores and sperm also reflect broader evolutionary strategies. Asexual reproduction via spores allows for rapid colonization of new habitats, as seen in mold spreading across a damp surface. Sexual reproduction, facilitated by sperm, introduces genetic variation, which enhances adaptability over generations. For example, the sexual reproduction of coral reefs through sperm and egg release ensures genetic diversity, crucial for resilience against climate change. Spores, however, enable organisms like tardigrades to survive in space, showcasing their unparalleled hardiness.

In summary, spores and sperm are not merely different in structure but in their core functions and survival strategies. Spores prioritize endurance and asexual replication, thriving in adversity, while sperm focus on mobility and genetic fusion, driving sexual reproduction. Recognizing these distinctions not only deepens our understanding of biology but also informs practical applications, from preserving endangered species to advancing medical technologies. Whether in a laboratory or the wild, the unique roles of spores and sperm underscore the diversity of life’s reproductive tactics.

Does Your EA Account Work to Access Spore? A Guide

You may want to see also

Motility: Sperm are actively motile with tails; spores are passive and dispersed by wind/water

Sperm and spores, though both reproductive units, exhibit stark differences in their approach to mobility. Sperm, the male reproductive cells, are equipped with a tail-like structure called a flagellum, which propels them through fluid environments, such as the female reproductive tract. This active motility is essential for sperm to reach and fertilize the egg, a process that requires energy and precision. In contrast, spores, the reproductive units of plants, fungi, and some bacteria, lack any means of self-propulsion. They are passive entities, relying on external forces like wind, water, or animal carriers for dispersal.

Consider the journey of a sperm cell: upon ejaculation, millions of sperm are released into the vagina, where they must navigate through the cervix and uterus to reach the fallopian tubes. This arduous trek is fueled by the sperm's flagellum, which whips back and forth at a rate of 10-15 times per second, propelling the cell forward at a speed of approximately 1-4 millimeters per minute. To put this into perspective, a single sperm cell can travel the length of a human hair (about 1 centimeter) in roughly 25 minutes. This remarkable feat of motility is a testament to the sperm's specialized design, which prioritizes speed and agility over other functions.

In contrast, spores adopt a more passive strategy for dispersal. Take, for instance, the spores of ferns, which are produced in structures called sporangia and released into the air. These lightweight, single-celled spores can be carried by wind currents for miles, eventually settling in a new location where they can germinate and grow into a new plant. Similarly, fungal spores, such as those of mushrooms, are often dispersed by wind or water, allowing them to colonize new substrates and environments. This passive dispersal mechanism enables spores to reach distant locations without expending energy, making it an efficient strategy for species that produce large quantities of reproductive units.

The implications of these differing motility strategies are significant. For sperm, active motility is crucial for successful fertilization, as it allows them to compete with other sperm cells and navigate the complex environment of the female reproductive tract. In fact, studies have shown that sperm motility is a key factor in male fertility, with a minimum of 40% progressively motile sperm required for normal fertility. On the other hand, spores' passive dispersal mechanism enables them to colonize new environments and adapt to changing conditions, contributing to the resilience and diversity of plant and fungal ecosystems.

To optimize sperm motility, certain lifestyle factors can play a role. For example, maintaining a healthy diet rich in antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, can help protect sperm cells from oxidative stress and improve motility. Additionally, avoiding exposure to toxins, such as cigarette smoke and heavy metals, can help preserve sperm function. For individuals struggling with fertility issues, assisted reproductive technologies like intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) can be used to select and inject a single, highly motile sperm directly into an egg, bypassing the need for natural fertilization. By understanding the unique motility characteristics of sperm and spores, we can appreciate the diverse strategies employed by different organisms to ensure successful reproduction and dispersal.

Can HEPA Filters Effectively Remove Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic Material: Spores contain full genetic sets for independent life; sperm carry half the genetic material

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, differ fundamentally in their genetic payload. Spores, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, carry a complete set of genetic material, enabling them to develop into a new organism independently. This self-sufficiency is critical for survival in harsh environments, where spores can remain dormant for years until conditions improve. In contrast, sperm cells, produced by animals and some plants, carry only half the genetic material required for life. Their role is to fuse with an egg cell, which also carries half the genetic material, to form a zygote with a full genetic set. This division of labor ensures genetic diversity in offspring, a key advantage in evolving populations.

Consider the practical implications of this genetic difference. For gardeners, understanding that spores contain a full genetic set explains why a single spore can grow into a mature fern or mushroom without a partner. This knowledge informs techniques like spore collection and sowing, where precision in humidity and light conditions can yield successful germination. Conversely, in animal breeding, the fact that sperm carries only half the genetic material highlights the importance of selecting both parents carefully to achieve desired traits in offspring. For instance, in dairy cattle breeding, bulls are chosen based on their genetic potential for milk production, which is then complemented by the genetic contribution of the cow.

From an evolutionary perspective, the genetic completeness of spores versus the half-set in sperm reflects different survival strategies. Spores, often produced in vast quantities, rely on numbers and resilience to ensure at least some land in favorable conditions. Their ability to survive extreme temperatures, desiccation, and radiation makes them ideal for colonizing new or recovering environments. Sperm, on the other hand, are part of a more targeted reproductive strategy. Their mobility and short lifespan require immediate access to an egg, but this system fosters genetic recombination, increasing adaptability in changing ecosystems. For example, coral reefs rely on synchronized mass spawning events, where sperm and eggs are released simultaneously to maximize fertilization chances, despite the sperm’s limited viability.

A persuasive argument for the importance of this genetic distinction lies in its impact on conservation efforts. Preserving plant species through spore banking is a viable strategy because spores’ complete genetic material allows for long-term storage and future regeneration. Organizations like the Millennium Seed Bank store spores and seeds in controlled environments, safeguarding biodiversity against climate change and habitat loss. In contrast, preserving animal species often requires more complex methods, such as artificial insemination or embryo freezing, due to the sperm’s dependency on a complementary egg. This underscores the need for integrated approaches in conservation, tailored to the reproductive mechanisms of each species.

Finally, a comparative analysis reveals how these genetic differences influence human applications. In agriculture, spore-producing crops like ferns or mosses are cultivated for their ability to regenerate from small fragments, a trait rooted in their complete genetic material. Techniques like tissue culture exploit this property to produce disease-free plants rapidly. In contrast, sperm’s role in selective breeding has driven advancements in genetics, from hybrid crops to genetically modified organisms. For instance, in aquaculture, sperm from high-performing fish is used to inseminate eggs, improving growth rates and disease resistance in farmed populations. Understanding these genetic distinctions not only deepens our appreciation of biology but also enhances our ability to harness these mechanisms for innovation and sustainability.

Inhaling Spores: Uncovering the Hidden Health Risks and Causes

You may want to see also

Lifespan: Spores can remain dormant for years; sperm have a short lifespan, often hours or days

Spores and sperm, though both reproductive units, exhibit stark differences in their lifespans, a critical factor in their survival strategies. While sperm are designed for immediate action, spores are the masters of patience, capable of enduring dormancy for years, even decades, under adverse conditions. This disparity in longevity is a fascinating adaptation that highlights the diverse ways life ensures its continuity.

Consider the journey of a sperm cell: once released, it has a narrow window of opportunity to fertilize an egg, typically ranging from a few hours to a few days. This short lifespan is a high-stakes gamble, as sperm must navigate a hostile environment, competing with millions of others to reach their target. In humans, for instance, sperm can survive inside the female reproductive tract for up to 5 days, but their motility and fertility decline rapidly after 72 hours. This urgency is a driving force behind the rapid reproductive cycle of many species, ensuring the continuation of their genetic lineage.

In contrast, spores embrace a strategy of endurance. Produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, spores can enter a state of dormancy, slowing their metabolic processes to a near halt. This allows them to withstand extreme conditions such as drought, heat, or cold, which would be fatal to most other forms of life. For example, bacterial endospores can survive for thousands of years, with some studies suggesting they could remain viable for up to 250 million years under optimal conditions. This remarkable resilience is achieved through a tough outer coating and minimal internal activity, enabling spores to bide their time until the environment becomes favorable for growth.

The practical implications of these lifespans are profound. For sperm, the short lifespan necessitates precise timing and optimal conditions for successful reproduction. In assisted reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilization (IVF), sperm are often cryopreserved to extend their viability, but even then, their usable lifespan is limited. On the other hand, the longevity of spores has significant applications in agriculture and conservation. Seed banks, for instance, leverage the dormancy of plant spores to preserve genetic diversity, storing seeds in controlled environments to ensure their viability for future generations.

In essence, the lifespan of spores and sperm reflects their distinct evolutionary strategies. Sperm thrive on immediacy, embodying the urgency of life’s fleeting opportunities. Spores, however, embody patience, a testament to the power of persistence in the face of adversity. Understanding these differences not only sheds light on the intricacies of reproduction but also offers practical insights for fields ranging from medicine to ecology. Whether it’s optimizing fertility treatments or preserving biodiversity, the contrasting lifespans of spores and sperm provide valuable lessons in adaptability and survival.

Can Botulinum Spores Survive Stomach Acid? Unraveling the Truth

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are reproductive structures produced by plants, fungi, and some microorganisms, primarily for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions, while sperm are male reproductive cells in animals and some plants, designed to fertilize female eggs for sexual reproduction.

Spores are typically single-celled, hardy structures with thick protective walls, often containing stored nutrients and genetic material. Sperm, in contrast, are specialized cells with a tail (flagellum) for motility, minimal cytoplasm, and a nucleus containing genetic material, optimized for mobility and fertilization.

No, spores are generally involved in asexual reproduction or alternation of generations (e.g., in plants), while sperm are exclusively involved in sexual reproduction, requiring the fusion with an egg to form a zygote.