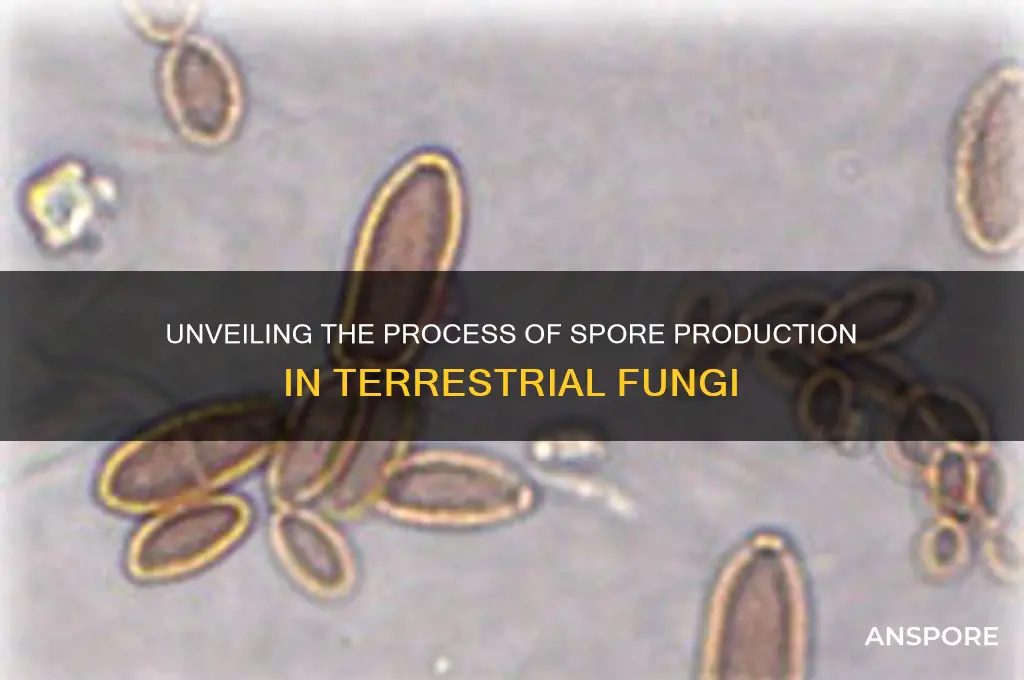

Terrestrial fungi employ diverse strategies to produce spores, which are essential for their survival, dispersal, and reproduction. These microscopic structures are typically generated through specialized structures like sporangia, asci, or basidia, depending on the fungal group. In zygomycetes, for example, spores form within sporangia, while in ascomycetes, they develop inside asci following a process called ascogenous development. Basidiomycetes, on the other hand, produce spores on basidia, often in structures like gills or pores. The production of spores involves intricate cellular processes, including meiosis and mitosis, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on fungal biology but also highlights their ecological roles in nutrient cycling and ecosystem dynamics.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangiospores Formation: Spores develop inside sporangia, released upon maturity via sporangium rupture

- Conidiospores Production: Asexual spores form on conidiophores, produced externally by budding or fragmentation

- Zygospores Development: Sexual spores result from zygote formation post-gametangia fusion in compatible fungi

- Ascospores Creation: Sexual spores develop inside asci, formed post-karyogamy in Ascomycetes

- Basidiospores Generation: Sexual spores grow on basidia, produced externally in Basidiomycetes

Sporangiospores Formation: Spores develop inside sporangia, released upon maturity via sporangium rupture

Sporangiospores represent a critical reproductive mechanism in terrestrial fungi, particularly within the Zygomycota and certain Basidiomycota groups. Unlike other spore types, sporangiospores develop within a specialized structure called the sporangium, a sac-like organ that serves as both nursery and launchpad. This process begins with the maturation of hyphae, the filamentous structures that constitute the fungal body. At specific developmental stages or in response to environmental cues, these hyphae differentiate to form sporangia. Inside each sporangium, haploid spores are produced through mitosis, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability. The sporangium acts as a protective chamber, shielding the developing spores from desiccation, predation, and other environmental stressors until they reach maturity.

The release of sporangiospores is a dramatic event, triggered by the rupture of the sporangium wall. This mechanism is both efficient and economical, as it relies on the natural weakening of the sporangium’s cell wall over time. Environmental factors such as humidity, temperature, and light can accelerate this process, ensuring spores are dispersed under optimal conditions. For example, in *Pilobolus*, a fungus commonly found on herbivorous animal dung, the sporangium ruptures explosively, propelling spores up to 2 meters away. This adaptation maximizes dispersal range, increasing the likelihood of colonization in new habitats. The timing and force of sporangium rupture are finely tuned to the fungus’s ecological niche, highlighting the precision of this reproductive strategy.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporangiospore formation is essential for managing fungal populations in agriculture and horticulture. For instance, *Rhizopus stolonifer*, a common cause of fruit rot, relies on sporangiospores for propagation. To mitigate its spread, growers can implement strategies such as reducing humidity levels, which delay sporangium maturation, or using fungicides that target sporangium development. Conversely, in mycoremediation—the use of fungi to degrade pollutants—sporangiospore-producing fungi can be cultivated under controlled conditions to ensure efficient spore production. By manipulating environmental factors like light exposure and nutrient availability, practitioners can optimize sporangium formation and spore release, enhancing the fungi’s effectiveness in breaking down contaminants.

Comparatively, sporangiospore formation differs significantly from other fungal reproductive methods, such as conidia production in Ascomycota or basidiospore formation in Basidiomycota. While conidia are produced externally on specialized structures and basidiospores are ejected from club-shaped basidia, sporangiospores are entirely dependent on the sporangium for development and dispersal. This reliance on a single structure makes sporangiospore-producing fungi more vulnerable to environmental disruptions but also more specialized in their reproductive ecology. For example, the explosive discharge of *Pilobolus* spores is unparalleled in other fungal groups, showcasing the unique adaptations of sporangiospore-producing species.

In conclusion, sporangiospore formation is a fascinating and highly specialized process that underscores the diversity of fungal reproductive strategies. By encapsulating spores within a sporangium and releasing them via rupture, these fungi balance protection with efficient dispersal. Whether in natural ecosystems or applied contexts, this mechanism offers valuable insights into fungal biology and practical tools for managing fungal populations. For enthusiasts and professionals alike, studying sporangiospores provides a window into the intricate ways fungi adapt to and thrive in terrestrial environments.

Are Psilocybin Spores Illegal? Understanding the Legal Landscape

You may want to see also

Conidiospores Production: Asexual spores form on conidiophores, produced externally by budding or fragmentation

Conidiospores, a prevalent form of asexual spores in terrestrial fungi, are produced externally on specialized structures called conidiophores. This process, known as conidiogenesis, is a fascinating example of fungal reproduction that relies on either budding or fragmentation. Unlike sexual spores, which require the fusion of gametes, conidiospores are formed through mitotic divisions, making them a rapid and efficient means of propagation. This method allows fungi to colonize new environments quickly, particularly in nutrient-rich or competitive habitats where speed is advantageous.

The production of conidiospores begins with the development of conidiophores, which emerge from the fungal hyphae. These structures can vary widely in shape, size, and branching patterns, reflecting the diversity of fungal species. Once formed, conidiophores serve as the foundation for spore production. In budding, a small outgrowth, or bud, develops on the conidiophore and gradually detaches to form a mature conidiospore. Fragmentation, on the other hand, involves the division of the conidiophore itself into multiple spore-like fragments, each capable of growing into a new fungus. Both mechanisms highlight the adaptability of fungi in dispersing their genetic material.

For practical applications, understanding conidiospore production is crucial in fields like agriculture and medicine. For instance, farmers can manage fungal pathogens by disrupting conidiophore development or spore dispersal, reducing crop losses. In laboratories, researchers often cultivate fungi on agar plates under controlled conditions (e.g., 25°C and 60% humidity) to study conidiogenesis. A simple tip for hobbyists: observe conidiophores under a 40x microscope to witness budding or fragmentation firsthand, using a sterile needle to transfer fungal samples onto slides.

Comparatively, conidiospores differ from other asexual spores, such as chlamydospores, in their external formation and rapid release. While chlamydospores are thick-walled and serve as survival structures, conidiospores are lightweight and designed for immediate dispersal. This distinction underscores the strategic diversity of fungal reproduction. By focusing on conidiophores, scientists can develop targeted interventions, such as antifungal agents that inhibit conidiophore growth, offering precise control over fungal populations.

In conclusion, conidiospore production exemplifies the ingenuity of terrestrial fungi in adapting to their environments. Whether through budding or fragmentation, this asexual method ensures rapid and widespread dispersal, making it a key area of study for both theoretical and applied mycology. By mastering the intricacies of conidiogenesis, we unlock new possibilities for managing fungi in agriculture, medicine, and beyond.

Bacillus Megaterium: Unveiling Its Spore-Forming Capabilities and Significance

You may want to see also

Zygospores Development: Sexual spores result from zygote formation post-gametangia fusion in compatible fungi

In the intricate world of terrestrial fungi, zygospores represent a fascinating mechanism of sexual reproduction, ensuring genetic diversity and survival across generations. This process begins with the fusion of gametangia, specialized structures that house compatible haploid gametes. When two such gametangia from different mating types come into contact, their cell walls dissolve, allowing the gametes to merge and form a diploid zygote. This zygote then develops into a thick-walled zygospore, a resilient structure capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. Unlike asexual spores, zygospores are the product of genetic recombination, offering evolutionary advantages by introducing new traits into fungal populations.

The development of zygospores is a highly regulated process, often triggered by environmental cues such as nutrient scarcity or changes in humidity. For example, in the fungus *Zygorhynchus* spp., compatible hyphae respond to these signals by differentiating into gametangia. The fusion of these structures is facilitated by pheromone signaling, ensuring that only compatible individuals mate. Once formed, the zygospore undergoes a period of dormancy, during which its thick wall protects the genetic material from desiccation, predation, and extreme temperatures. This dormancy can last for months or even years, depending on the species and environmental conditions.

Practical observation of zygospore development can be achieved through laboratory cultivation of compatible fungal strains under controlled conditions. For instance, placing *Rhizopus stolonifer* (a common bread mold) on nutrient-rich agar plates and maintaining a temperature of 25–30°C can induce gametangia formation. By introducing strains of opposite mating types, researchers can observe the fusion process under a microscope, noting the zygospore’s characteristic dark pigmentation and spherical shape. This method is valuable for studying genetic diversity and the mechanisms of fungal survival in terrestrial ecosystems.

Comparatively, zygospores differ from other fungal spores, such as conidia or basidiospores, in their origin and function. While asexual spores are produced through mitosis and serve primarily for rapid colonization, zygospores are the result of meiosis and are crucial for long-term survival and adaptation. This distinction highlights the dual reproductive strategies employed by fungi, balancing immediate proliferation with genetic innovation. Understanding these differences is essential for fields like agriculture, where fungal pathogens and beneficial species alike rely on spore production for their life cycles.

In conclusion, zygospore development exemplifies the sophistication of fungal reproductive strategies. By combining genetic recombination with environmental resilience, fungi ensure their persistence in diverse terrestrial habitats. For enthusiasts and researchers alike, studying this process offers insights into fungal biology and its broader ecological implications. Whether in a laboratory setting or natural environment, observing zygospore formation underscores the remarkable adaptability of these organisms.

Does Diphtheria Produce Spores? Unraveling the Bacteria's Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ascospores Creation: Sexual spores develop inside asci, formed post-karyogamy in Ascomycetes

In the intricate world of terrestrial fungi, ascomycetes stand out for their unique method of spore production. Ascospores, the sexual spores of these fungi, are not just ejected into the environment haphazardly. Instead, they develop within specialized structures called asci, which form only after a precise genetic union known as karyogamy. This process ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, key traits for survival in diverse ecosystems.

Consider the lifecycle of *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, a well-studied ascomycete. After two haploid cells (often of opposite mating types, a and α) detect each other via pheromones, they undergo plasmogamy, fusing their cytoplasm but keeping their nuclei separate. Karyogamy follows, where the nuclei merge, creating a diploid cell. This cell then undergoes meiosis, producing four haploid nuclei. Each nucleus is encased in an ascus, where it develops into an ascospore. The ascus acts as a protective chamber, ensuring the spores mature safely before dispersal.

The formation of asci is a critical step, as it not only safeguards the developing ascospores but also facilitates their eventual release. In species like *Neurospora crassa*, the asci become turgid and burst open, ejecting the spores with force. This mechanism maximizes dispersal range, increasing the chances of colonization in new habitats. For gardeners or mycologists cultivating ascomycetes, understanding this process can optimize spore collection. For instance, maintaining a humid environment (70-80% relative humidity) and a temperature of 22-25°C mimics ideal conditions for ascus development and spore release.

Comparatively, basidiomycetes produce spores on external basidia, leaving them more exposed to environmental stressors. Ascomycetes, however, invest energy in asci formation, a strategy that pays off in stability and protection. This distinction highlights the evolutionary ingenuity of ascomycetes, which dominate terrestrial ecosystems with over 64% of known fungal species. For researchers, this makes ascomycetes prime candidates for studying fungal genetics and ecology.

In practical terms, harnessing ascospore production can benefit agriculture and biotechnology. For example, *Trichoderma* species, prolific ascospore producers, are used as biofungicides to combat plant pathogens. By manipulating environmental conditions to favor ascus formation, farmers can enhance the efficacy of these biocontrol agents. Similarly, in lab settings, inducing karyogamy through controlled mating assays allows scientists to study genetic recombination in ascomycetes, advancing our understanding of fungal evolution.

In conclusion, the creation of ascospores within asci post-karyogamy is a testament to the sophistication of ascomycetes. From protecting genetic material to ensuring efficient dispersal, this process underscores the fungi’s adaptability. Whether in nature, agriculture, or research, mastering this mechanism opens doors to leveraging ascomycetes’ potential. For anyone working with these fungi, recognizing the importance of asci and karyogamy is not just academic—it’s practical.

Botulism Spores in the Air: Uncovering the Hidden Presence

You may want to see also

Basidiospores Generation: Sexual spores grow on basidia, produced externally in Basidiomycetes

In the intricate world of terrestrial fungi, basidiospores stand out as a marvel of sexual reproduction, uniquely produced on club-shaped structures called basidia. These spores are the hallmark of Basidiomycetes, a diverse phylum encompassing mushrooms, puffballs, and rusts. Unlike asexual spores, basidiospores arise through a complex process involving karyogamy and meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity. This external spore production on basidia distinguishes Basidiomycetes from other fungal groups, making them a focal point in understanding fungal life cycles.

The formation of basidiospores begins with the fusion of hyphae from compatible mating types, a process known as plasmogamy. This union creates a dikaryotic mycelium, where two haploid nuclei coexist in a single cell. As the mycelium matures, it develops specialized structures called basidiocarps (fruiting bodies), such as mushrooms. Within these basidiocarps, club-shaped basidia emerge, each bearing four haploid nuclei. Meiosis occurs, followed by nuclear migration, resulting in four haploid basidiospores attached to the basidium. These spores are then released into the environment, often through mechanisms like wind or water, to initiate new fungal colonies.

One of the most fascinating aspects of basidiospore generation is the precision with which spores are ejected. In many Basidiomycetes, such as the common button mushroom (*Agaricus bisporus*), basidiospores are launched with remarkable force. This is achieved through a sudden release of water droplets at the basidium’s surface, creating a miniature "puff" that propels spores up to several millimeters. This mechanism ensures efficient dispersal, increasing the likelihood of colonization in new habitats. Practical observation of this process can be done by placing a mature mushroom cap on a sheet of dark paper overnight, revealing a spore print that mirrors the arrangement of gills or pores.

While basidiospore production is a natural process, understanding it has practical applications in agriculture and mycology. For instance, mushroom cultivators manipulate environmental conditions like humidity (85-95%) and temperature (22-25°C) to optimize basidiocarp formation. Additionally, knowing the spore dispersal mechanism aids in disease management, as basidiospores of rust fungi (*Puccinia* spp.) can devastate crops like wheat and soybeans. By monitoring spore release patterns, farmers can implement timely interventions, such as fungicide application during peak spore production periods.

In conclusion, basidiospore generation exemplifies the sophistication of fungal reproductive strategies. From the dikaryotic mycelium to the explosive spore discharge, each step is finely tuned for survival and propagation. Whether in the wild or in cultivation, understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation of fungal biology but also empowers practical applications in agriculture and conservation. Observing basidiospores under a microscope or witnessing their dispersal in nature offers a tangible connection to the hidden world of fungi, reminding us of their vital role in ecosystems.

Does Spore Require EA App Integration for Optimal Gameplay?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores in terrestrial fungi are produced through specialized structures such as sporangia, asci, or basidia, depending on the fungal group. These structures undergo meiosis or mitosis to generate spores, which are then released into the environment for dispersal.

The main types of spores produced by terrestrial fungi include asexual spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) and sexual spores (e.g., asci spores, basidiospores). Asexual spores are produced via mitosis, while sexual spores result from meiosis.

Terrestrial fungi release spores through various mechanisms, such as wind dispersal, water splash, or animal vectors. For example, some fungi forcibly eject spores (ballistospores), while others rely on passive release from mature structures like gills or pustules.

Environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, light, and nutrient availability significantly influence spore production in terrestrial fungi. Optimal conditions promote sporulation, while stress or suboptimal conditions may delay or inhibit the process.