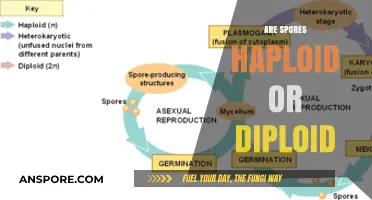

Spores, which are reproductive structures found in plants, fungi, and some protozoa, play a crucial role in the life cycles of these organisms. Understanding whether spores are produced by mitosis or meiosis is essential to grasp their function and significance. Mitosis is a type of cell division that results in two genetically identical daughter cells, typically involved in growth and repair, while meiosis is a specialized form of cell division that produces four genetically unique haploid cells, primarily for sexual reproduction. In the context of spore formation, the process varies depending on the organism and the type of spore. For instance, in fungi, spores such as conidia are often produced through mitosis, serving as asexual reproductive units. In contrast, spores like those in ferns and mosses, which are part of their sexual life cycle, are typically produced through meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity. Thus, the production of spores can involve either mitosis or meiosis, depending on the organism and the specific role of the spore in its life cycle.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Process of Spore Formation | Spores are produced through meiosis, a type of cell division that results in haploid cells (cells with half the number of chromosomes). |

| Type of Spores | Haploid spores (e.g., spores in fungi, plants like ferns, and some algae). |

| Purpose | Spores serve as reproductive units and are often used for dispersal and survival in harsh conditions. |

| Contrast with Mitosis | Mitosis produces diploid cells (cells with a full set of chromosomes) and is involved in growth, repair, and asexual reproduction, not spore formation. |

| Examples of Organisms | Fungi (e.g., molds, mushrooms), plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and some algae produce spores via meiosis. |

| Genetic Diversity | Meiosis introduces genetic variation through crossing over and independent assortment, which is beneficial for spore-producing organisms. |

| Life Cycle Stage | Spores are typically part of the alternation of generations in plants and fungi, transitioning between haploid and diploid phases. |

| Key Difference | Spores are haploid and result from meiosis, while cells produced by mitosis are diploid and genetically identical to the parent cell. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores result from mitosis for asexual reproduction, not meiosis

- Plant Spores: Plants produce spores via meiosis for alternation of generations

- Bacterial Spores: Bacterial endospores form through asexual processes, not mitosis or meiosis

- Mitosis vs. Meiosis: Mitosis creates identical cells; meiosis produces genetically diverse gametes/spores

- Sporulation Process: Meiosis in spore formation ensures genetic variation in offspring

Spores in Fungi: Most fungal spores result from mitosis for asexual reproduction, not meiosis

Fungal spores are often misunderstood as products of meiosis, akin to those in plants. However, the majority of fungal spores arise from mitosis, a process that ensures genetic consistency and rapid proliferation. This asexual method allows fungi to colonize environments swiftly, as seen in the ubiquitous dispersal of *Aspergillus* spores in indoor and outdoor settings. Unlike meiosis, which introduces genetic variation, mitosis preserves the parent’s genetic identity, making it ideal for stable, clonal reproduction in stable environments.

Consider the lifecycle of *Penicillium*, a common mold. When conditions are favorable, it produces conidia—asexual spores formed through mitosis. These spores are lightweight and easily airborne, enabling the fungus to spread without relying on sexual reproduction. This strategy is particularly effective in nutrient-rich but unpredictable environments, where speed and consistency outpace the need for genetic diversity. For instance, a single *Penicillium* colony can release millions of conidia daily, each genetically identical to the parent.

Contrast this with meiosis, which occurs in fungi during sexual reproduction. Here, spores like ascospores or basidiospores are produced, but these are far less common and require specific conditions, such as the fusion of compatible hyphae. Meiosis introduces genetic recombination, beneficial for adapting to changing environments but inefficient for rapid colonization. For example, the sexual spores of *Coprinus comatus* (the shaggy mane mushroom) are produced only under precise environmental cues, unlike its asexual counterparts.

Practical implications of this distinction are significant. In agriculture, mitotic spores of fungi like *Fusarium* can quickly contaminate crops, as their clonal nature ensures consistent virulence. Controlling such fungi requires disrupting their asexual cycle, such as through fungicides targeting spore dispersal. Conversely, understanding meiotic spores helps in breeding programs, where genetic diversity is leveraged to develop resistant strains. For home gardeners, preventing mold growth involves reducing humidity—a key trigger for mitotic spore release.

In summary, while both mitosis and meiosis play roles in fungal reproduction, mitosis dominates in spore production for asexual replication. This process underpins fungi’s success in diverse ecosystems, from decomposing organic matter to infecting hosts. Recognizing this distinction not only clarifies fungal biology but also informs strategies for managing fungal growth, whether in industrial settings or everyday environments.

Do Gram-Negative Bacteria Form Spores? Unraveling the Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Plant Spores: Plants produce spores via meiosis for alternation of generations

Plants, unlike animals, rely on an intricate life cycle known as alternation of generations, where two distinct phases—sporophyte and gametophyte—alternate. Spores, the key to this cycle, are produced by the sporophyte generation through meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half. This process ensures genetic diversity, a critical factor for plant survival in changing environments. For instance, ferns release spores from the undersides of their fronds, each capable of growing into a new gametophyte, which then produces gametes to restart the cycle.

Understanding meiosis in spore production is essential for horticulture and agriculture. Gardeners cultivating mosses or ferns must recognize that spores require specific conditions—moisture, shade, and nutrient-rich substrates—to germinate successfully. In contrast, mitosis, which maintains the full chromosome set, is reserved for vegetative growth in plants. This distinction highlights why spores are not clones of the parent plant but genetically unique individuals, fostering adaptability in diverse ecosystems.

From an evolutionary perspective, meiosis in spore production is a strategic advantage. It allows plants to colonize harsh habitats, such as rocky outcrops or arid soils, where seeds might fail. For example, bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) thrive in these conditions due to their spore-based reproduction. Educators and hobbyists can demonstrate this by growing ferns from spores in a controlled environment, observing the transition from sporophyte to gametophyte under a microscope.

Practical applications extend to conservation efforts. Reintroducing spore-producing plants like lichens or ferns can restore degraded landscapes, as their spores disperse widely and establish quickly. However, caution is necessary: over-collection of spores from wild populations can disrupt ecosystems. Sustainable practices, such as cultivating spores in labs or greenhouses, ensure preservation while meeting demand for landscaping or research.

In summary, plant spores are the product of meiosis, driving the alternation of generations and ensuring genetic diversity. Whether for gardening, education, or conservation, understanding this process empowers individuals to harness its benefits responsibly. By respecting the delicate balance of spore production, we contribute to the resilience of plant life across the globe.

Pollen vs. Spores: Understanding the Difference in Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Bacterial Spores: Bacterial endospores form through asexual processes, not mitosis or meiosis

Bacterial endospores are a remarkable survival mechanism, but their formation defies the typical cellular processes of mitosis and meiosis. Unlike eukaryotic cells, which rely on these division methods for reproduction and genetic diversity, bacteria employ a unique asexual process to create endospores. This process, known as sporulation, is a highly regulated series of events triggered by environmental stress, such as nutrient depletion or extreme conditions. Understanding this distinction is crucial for fields like microbiology and biotechnology, where the resilience of bacterial spores poses both challenges and opportunities.

The sporulation process begins with a bacterial cell sensing adverse conditions. In response, it initiates a series of morphological and biochemical changes. The cell divides asymmetrically, forming a smaller cell (the forespore) within the larger mother cell. This forespore then undergoes a series of maturation steps, including the synthesis of a protective spore coat and the dehydration of its cytoplasm. The result is a dormant, highly resistant structure capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals. Notably, this process does not involve the genetic recombination seen in meiosis or the equal division of chromosomes in mitosis.

From a practical standpoint, the asexual nature of spore formation has significant implications. For instance, in food preservation, bacterial spores are a major concern because they can survive standard sterilization methods. Common practices like pasteurization (heating to 63°C for 30 minutes) are insufficient to eliminate spores, necessitating more aggressive techniques such as autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes). In biotechnology, however, the durability of spores is harnessed for applications like vaccine delivery and enzyme stabilization. Understanding the asexual process of sporulation allows scientists to develop targeted strategies for both combating and utilizing these resilient structures.

Comparatively, while fungal and plant spores often arise from meiosis, bacterial endospores stand apart due to their asexual origin. This difference highlights the diversity of spore-forming mechanisms across organisms. For example, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus*, are produced through meiosis and play a role in sexual reproduction. In contrast, bacterial endospores are purely a survival tool, devoid of genetic variation. This distinction is vital for researchers and practitioners in fields like agriculture and medicine, where spore behavior directly impacts outcomes.

In conclusion, bacterial endospores are a testament to the ingenuity of microbial survival strategies. Their formation through asexual processes, distinct from mitosis and meiosis, underscores the unique biology of bacteria. By grasping this mechanism, we can better address challenges like food spoilage and antibiotic resistance while leveraging spores for innovative applications. Whether in the lab or the field, this knowledge equips us to navigate the complexities of bacterial resilience with precision and purpose.

Lysol's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Ringworm Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Mitosis vs. Meiosis: Mitosis creates identical cells; meiosis produces genetically diverse gametes/spores

Spores, those resilient survival structures of plants, fungi, and some bacteria, are not produced by mitosis. This might seem counterintuitive, given that mitosis is the process of cell division that results in two genetically identical daughter cells. However, spore formation is a specialized process that requires genetic diversity to ensure the survival of the species in varying environments. This is where meiosis comes into play.

Understanding the Process: Meiosis and Genetic Diversity

Meiosis is a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, producing four haploid cells (gametes or spores) with unique genetic combinations. This reduction division is crucial for sexual reproduction, as it allows for the fusion of two haploid gametes (e.g., sperm and egg) to form a diploid zygote. In the case of spores, meiosis ensures that each spore has a distinct genetic makeup, increasing the chances of successful germination and growth in diverse conditions. For instance, in ferns, meiosis occurs in the sporangia, resulting in the production of haploid spores that can develop into gametophytes.

Comparing Mitosis and Meiosis in Spore Production

While mitosis is essential for growth, repair, and asexual reproduction, it does not contribute to spore formation. Mitosis produces identical cells, which is vital for maintaining tissue integrity and ensuring proper development. In contrast, meiosis is specifically adapted for generating genetic diversity. Consider the life cycle of a fungus: during the sexual phase, meiosis produces haploid spores (ascospores or basidiospores) that can disperse and colonize new environments. This diversity is key to the fungus's ability to adapt and thrive in various ecological niches.

Practical Implications: Why Genetic Diversity Matters

The genetic diversity produced by meiosis in spores has significant ecological and agricultural implications. For example, in crop plants, spores with varied genetic traits can lead to the development of new varieties with improved resistance to pests, diseases, or environmental stresses. Farmers and plant breeders often exploit this diversity through selective breeding or genetic engineering. Similarly, in the study of fungi, understanding spore diversity helps in managing fungal diseases and harnessing beneficial fungi for biotechnology applications.

Takeaway: The Role of Meiosis in Spore Formation

In summary, spores are not produced by mitosis but by meiosis, a process that ensures genetic diversity. This diversity is essential for the survival and adaptation of organisms in changing environments. Whether in plants, fungi, or other spore-producing organisms, meiosis plays a critical role in generating the variability needed for evolution and ecological success. By contrasting mitosis and meiosis, we gain a deeper understanding of how these cellular processes contribute to the complexity and resilience of life.

Effective Methods to Remove Mold Spores from Your Clothes Safely

You may want to see also

Sporulation Process: Meiosis in spore formation ensures genetic variation in offspring

Spores, the resilient survival structures of many organisms, are not products of mitosis but of meiosis, a specialized cell division process that introduces genetic variation. This distinction is crucial because it underpins the adaptability and evolutionary success of spore-producing species. While mitosis results in genetically identical daughter cells, meiosis shuffles genetic material through crossing over and independent assortment, ensuring that each spore carries a unique combination of traits. This genetic diversity is particularly vital for organisms like fungi, plants, and certain protozoa, which rely on spores to endure harsh conditions and colonize new environments.

Consider the sporulation process in fungi, a prime example of meiosis in action. When environmental conditions deteriorate—such as nutrient depletion or desiccation—fungal hyphae initiate sporulation. The process begins with the formation of a diploid zygote, which undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores. During meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up, exchange segments via crossing over, and then segregate, reducing the chromosome number by half. Meiosis II further divides these cells, yielding four haploid spores. This two-step division not only ensures genetic recombination but also maximizes the potential for variation, increasing the likelihood that at least some spores will thrive in unpredictable environments.

The role of meiosis in spore formation extends beyond fungi to plants, particularly in the life cycles of ferns, mosses, and seedless vascular plants. For instance, in ferns, the sporophyte (diploid) phase produces sporangia, structures where meiosis occurs to generate haploid spores. These spores develop into gametophytes, which, upon fertilization, restore the diploid phase. This alternation of generations, facilitated by meiosis, ensures that each generation of spores carries novel genetic combinations, enhancing the species’ resilience to environmental changes. Without meiosis, these organisms would lack the genetic plasticity needed to adapt to shifting climates or habitats.

Practical implications of this process are evident in agriculture and conservation. For example, understanding sporulation in crop pathogens like *Phytophthora* or *Fusarium* can inform strategies to combat fungal diseases. Since spores from meiosis exhibit genetic diversity, fungicides must target broad-spectrum mechanisms rather than specific strains. Similarly, in conservation efforts for endangered plant species, promoting genetic diversity through spore collection and propagation can improve the long-term viability of reintroduced populations. By harnessing the natural variation generated by meiosis, scientists can develop more robust and resilient species.

In conclusion, the sporulation process hinges on meiosis to ensure genetic variation in offspring, a feature that distinguishes spores from mitotically produced cells. This mechanism is not merely a biological curiosity but a cornerstone of survival and adaptation for spore-producing organisms. Whether in fungi, plants, or protozoa, meiosis during spore formation equips these organisms with the diversity needed to thrive in dynamic environments. Recognizing this process underscores its significance in both natural ecosystems and applied fields, from agriculture to conservation.

Effective Milky Spore Application: A Step-by-Step Guide for Lawn Grub Control

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are typically produced by meiosis, a type of cell division that results in genetically diverse haploid cells.

Spores are produced through meiosis because it ensures genetic diversity and reduces the chromosome number to haploid, which is essential for the life cycle of many organisms, such as fungi and plants.

No, spores are not produced by mitosis. Mitosis results in genetically identical diploid cells, which is not the purpose of spore formation.

Meiosis plays a crucial role in spore production by creating genetically unique haploid cells, which can later develop into new individuals or structures, such as gametophytes in plants.