Fungi are unique organisms that employ two distinct reproductive systems to ensure their survival and propagation: sexual and asexual reproduction. One of the most fascinating aspects of fungal reproduction is their ability to produce spores, which serve as the primary means of dispersal and reproduction. Asexual spores, such as conidia, are produced through mitosis and allow fungi to rapidly colonize new environments, while sexual spores, like asci and basidiospores, result from meiosis and promote genetic diversity. This dual reproductive strategy enables fungi to adapt to diverse ecological niches, withstand harsh conditions, and maintain their presence in various ecosystems, highlighting their evolutionary success and ecological importance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproductive Systems | Fungi have two primary reproductive systems: asexual and sexual. |

| Asexual Reproduction | Involves the production of spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) without the fusion of gametes. Occurs via mitosis. |

| Sexual Reproduction | Involves the fusion of haploid gametes (e.g., from hyphae of compatible mating types) to form a diploid zygote, followed by meiosis. |

| Spores | Specialized cells produced by fungi for dispersal and survival. Types include asexual spores (e.g., conidia) and sexual spores (e.g., asci, basidiospores). |

| Spore Formation | Asexual spores form directly on hyphae or in sporangia, while sexual spores form within specialized structures like asci (Ascomycota) or basidia (Basidiomycota). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Spores are dispersed via wind, water, animals, or explosive mechanisms (e.g., in puffballs). |

| Survival Adaptations | Spores are highly resistant to harsh conditions (e.g., desiccation, temperature extremes), allowing fungi to survive in diverse environments. |

| Life Cycle | Fungi alternate between haploid (dominant) and diploid phases in their life cycle, known as the haploid-diploid life cycle. |

| Examples of Asexual Spores | Conidia (molds), sporangiospores (bread molds), and chlamydospores (thick-walled resting spores). |

| Examples of Sexual Spores | Ascospores (Ascomycota), basidiospores (Basidiomycota), and zygospores (Zygomycota). |

| Ecological Role | Spores enable fungi to colonize new habitats, decompose organic matter, and form symbiotic relationships (e.g., mycorrhizae, lichens). |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual reproduction promotes genetic recombination, increasing diversity and adaptability in fungal populations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporangiospores Formation: Spores develop inside sporangia, released through rupture, aiding in asexual reproduction and dispersal

- Conidiospores Production: Asexual spores form on conidiophores, dispersed by wind, water, or animals for survival

- Sexual Reproduction: Involves plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis, producing genetically diverse spores for adaptation

- Perfect Fungi: Have both sexual and asexual reproductive systems, ensuring survival in varying environments

- Imperfect Fungi: Lack sexual reproduction, relying solely on asexual spores for propagation and spread

Sporangiospores Formation: Spores develop inside sporangia, released through rupture, aiding in asexual reproduction and dispersal

Fungi employ a fascinating strategy for survival and propagation through the formation of sporangiospores, a process that showcases their adaptability and efficiency in asexual reproduction. This method begins with the development of spores within specialized structures called sporangia, which act as protective chambers for the maturing spores. Once the spores are fully formed, the sporangium ruptures, releasing them into the environment. This mechanism ensures widespread dispersal, allowing fungi to colonize new habitats and thrive in diverse conditions. The rupture-based release is particularly effective in environments where wind or water currents can carry the lightweight spores over significant distances.

Analyzing the sporangiospore formation process reveals its dual role in both reproduction and survival. Unlike sexual reproduction, which requires the fusion of gametes, sporangiospore production is asexual, enabling rapid multiplication without the need for a mate. This is especially advantageous in stable environments where genetic diversity is less critical. For instance, molds like *Rhizopus*, commonly found on bread, utilize this method to quickly spread across food surfaces. The efficiency of this system lies in its simplicity: a single sporangium can produce thousands of spores, each capable of developing into a new organism under favorable conditions.

To understand the practical implications, consider the steps involved in sporangiospore formation. First, the fungus develops a sporangiophore, a stalk-like structure that supports the sporangium. Inside the sporangium, spores grow through mitosis, a form of cell division that ensures genetic uniformity. Once mature, the sporangium wall weakens and eventually ruptures, releasing the spores. This process is highly regulated, often triggered by environmental cues such as humidity or nutrient availability. For gardeners or farmers dealing with fungal infestations, disrupting this cycle—for example, by reducing moisture—can limit spore dispersal and control fungal growth.

Comparatively, sporangiospore formation stands out from other fungal reproductive methods, such as zygospores or conidia, due to its reliance on rupture for dispersal. While zygospores result from sexual fusion and remain dormant until conditions improve, and conidia are released through passive mechanisms like wind, sporangiospores combine rapid production with active dispersal. This makes them particularly effective in environments where quick colonization is key. For example, in decaying organic matter, sporangiospore-producing fungi like *Mucor* can outcompete other microorganisms by rapidly spreading and consuming resources.

In conclusion, sporangiospore formation is a testament to fungi’s evolutionary ingenuity, balancing efficiency with adaptability. By encapsulating spores in sporangia and releasing them through rupture, fungi ensure both protection and dispersal. This method not only aids in asexual reproduction but also enhances their ability to survive in varied ecosystems. Whether in a laboratory, garden, or natural habitat, understanding this process provides valuable insights into fungal behavior and offers practical strategies for managing fungal growth. For instance, in controlled environments like greenhouses, monitoring humidity levels can prevent sporangium rupture and reduce spore-related issues. This knowledge underscores the importance of studying fungal reproductive systems in their full complexity.

Does Psychic Terrain Block Spore Abilities in Competitive Play?

You may want to see also

Conidiospores Production: Asexual spores form on conidiophores, dispersed by wind, water, or animals for survival

Fungi employ a remarkable strategy for survival through the production of conidiospores, asexual spores that form on specialized structures called conidiophores. These spores are not just a means of reproduction but a testament to the adaptability and resilience of fungal organisms. Conidiospores are lightweight and often produced in vast quantities, ensuring that even if a majority fail to germinate, a sufficient number will land in favorable environments to continue the species. This method of dispersal is a key factor in the success of fungi across diverse ecosystems, from soil and water to plant surfaces and even animal hosts.

The process of conidiospore production is both efficient and versatile. Conidiophores, the spore-bearing structures, can vary widely in shape and size depending on the fungal species, but their primary function remains consistent: to elevate and release spores into the environment. Dispersal mechanisms are equally diverse, with wind being the most common agent, carrying spores over long distances. Water, too, plays a significant role, especially in aquatic or damp environments, where spores can be washed into new habitats. Animals, including insects and larger fauna, inadvertently aid in dispersal by carrying spores on their bodies or through ingestion and excretion, highlighting the interconnectedness of ecosystems.

Understanding conidiospore production is crucial for both scientific research and practical applications. For instance, in agriculture, knowledge of how fungal spores disperse can inform strategies to control plant diseases caused by pathogenic fungi. Similarly, in medicine, recognizing the role of conidiospores in fungal infections can lead to more effective treatments and prevention methods. For hobbyists and professionals alike, observing conidiophores under a microscope can reveal the intricate beauty of fungal structures and provide insights into their life cycles.

Practical tips for studying conidiospores include using a simple setup with a light microscope and a slide prepared from a fungal culture or a natural sample. To enhance visibility, a stain like lactophenol cotton blue can be applied, though many conidiospores are visible without staining due to their size and pigmentation. For those interested in fungal ecology, collecting samples from different environments—such as decaying wood, leaf litter, or soil—can demonstrate the widespread presence and diversity of conidiophores. This hands-on approach not only deepens understanding but also fosters appreciation for the often-overlooked role of fungi in ecosystems.

In conclusion, conidiospore production exemplifies the ingenuity of fungal reproductive strategies. By forming asexual spores on conidiophores and utilizing multiple dispersal methods, fungi ensure their survival and proliferation in virtually every habitat on Earth. Whether through wind, water, or animal vectors, these spores bridge gaps between environments, contributing to the dynamic balance of ecosystems. For anyone intrigued by the natural world, exploring the mechanisms of conidiospore production offers a fascinating glimpse into the complexity and elegance of fungal life.

Does S. Marcescens Produce Spores? Unraveling the Mystery of Its Survival

You may want to see also

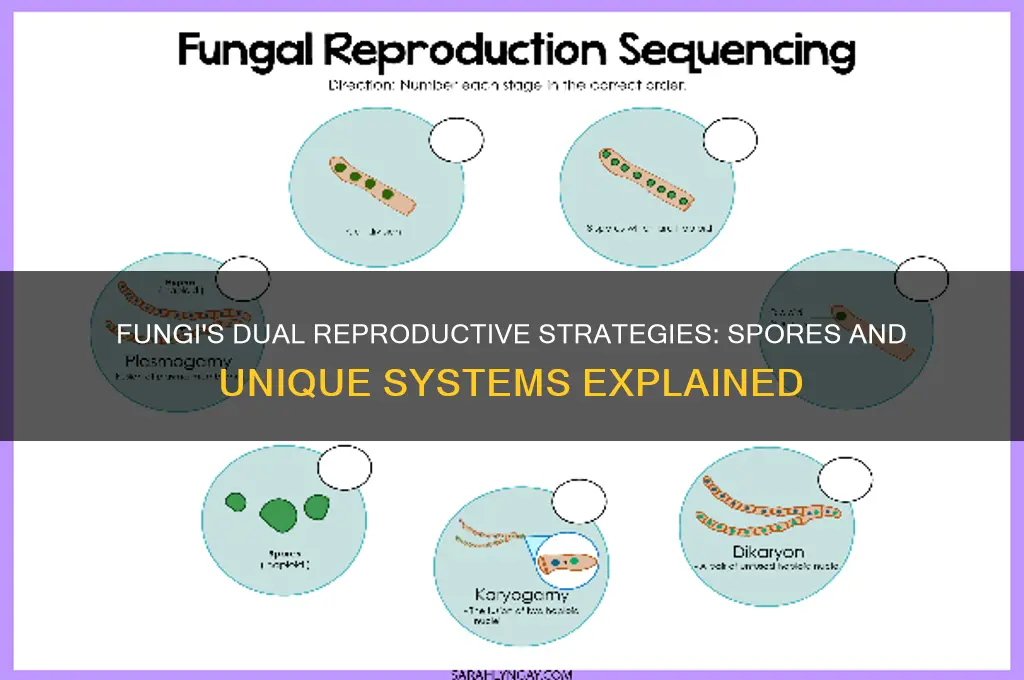

Sexual Reproduction: Involves plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis, producing genetically diverse spores for adaptation

Fungi employ a sophisticated sexual reproduction process that ensures genetic diversity, a key factor in their adaptability and survival across diverse environments. This process involves three critical stages: plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis. Each step is meticulously orchestrated to produce spores that carry unique genetic combinations, enabling fungal populations to respond effectively to changing conditions.

Plasmogamy marks the beginning of sexual reproduction in fungi, where two compatible hyphae fuse, merging their cytoplasm while keeping their nuclei separate. This stage is akin to a preliminary alliance, allowing the exchange of cellular material without immediate genetic recombination. For example, in the model fungus *Neurospora crassa*, plasmogamy occurs when haploid cells of opposite mating types (+ and -) come into contact, forming a heterokaryotic cell. This fusion is not just a physical merger but a strategic step to prepare for the next phase, ensuring that the genetic material is ready for further interaction.

Karyogamy follows plasmogamy, where the nuclei from the fused hyphae finally unite, forming a diploid nucleus. This stage is crucial for genetic recombination, as it sets the stage for meiosis. In species like *Aspergillus nidulans*, karyogamy is tightly regulated to ensure that only compatible nuclei fuse, preventing wasteful or harmful combinations. The diploid nucleus formed here is transient, existing solely to undergo meiosis, which restores the haploid state while shuffling genetic material.

Meiosis is the pinnacle of sexual reproduction in fungi, where the diploid nucleus undergoes two divisions to produce four haploid nuclei. These nuclei develop into spores, each genetically distinct due to crossing over during meiosis. For instance, in *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast), meiosis results in four ascospores housed in an ascus. This genetic diversity is vital for adaptation, as it equips fungal populations with a range of traits to withstand environmental stresses, such as temperature fluctuations or nutrient scarcity.

Practical implications of this process are profound. In agriculture, understanding fungal sexual reproduction helps in managing pathogens like *Fusarium graminearum*, which causes wheat scab. By disrupting plasmogamy or karyogamy, fungicides can prevent the formation of genetically diverse spores, reducing disease spread. Conversely, in biotechnology, harnessing meiosis in fungi like *Penicillium* species enhances the production of antibiotics by promoting genetic variability. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms, ensuring optimal conditions for plasmogamy—such as maintaining a humidity of 85-90% and a temperature of 22-25°C—can improve fruiting body formation.

In essence, the sexual reproduction of fungi is a finely tuned mechanism that leverages plasmogamy, karyogamy, and meiosis to generate genetic diversity. This diversity is not just a byproduct but a survival strategy, enabling fungi to thrive in ever-changing ecosystems. Whether combating fungal diseases or cultivating beneficial species, understanding these stages provides actionable insights for both scientific and practical applications.

Understanding Spores: Mitosis or Meiosis Production Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Perfect Fungi: Have both sexual and asexual reproductive systems, ensuring survival in varying environments

Fungi, often overlooked in the natural world, are masters of survival, thanks in part to their dual reproductive strategies. Perfect fungi, a term used to describe those with both sexual and asexual reproductive systems, exemplify this adaptability. These organisms can switch between methods depending on environmental conditions, ensuring their persistence across diverse habitats. For instance, when resources are abundant and conditions stable, sexual reproduction allows for genetic diversity, which can help populations withstand diseases and environmental changes. Conversely, in harsh or unpredictable environments, asexual reproduction provides a quick and efficient means to propagate without the need for a mate.

Consider the *Penicillium* genus, a perfect fungus commonly found in soil and decaying matter. When conditions are favorable, it produces specialized structures called ascocarps, where sexual reproduction occurs through the fusion of haploid cells, resulting in genetically diverse spores. However, when nutrients are scarce or the environment is stressful, *Penicillium* switches to asexual reproduction, producing conidia—single-celled spores that disperse easily and germinate rapidly. This dual strategy ensures that the fungus thrives in both stable and fluctuating ecosystems, from temperate forests to indoor environments.

The ability to toggle between reproductive modes is not just a survival tactic but also a mechanism for colonization. Asexual spores, being lightweight and numerous, can travel vast distances via wind or water, allowing fungi to colonize new territories quickly. Sexual reproduction, on the other hand, generates genetic variation, which is crucial for long-term survival in evolving environments. For example, in agricultural settings, fungi like *Aspergillus* use asexual spores to spread rapidly across crops, while sexual reproduction helps them develop resistance to fungicides, ensuring their continued presence despite human intervention.

Practical applications of this dual system are evident in industries such as food production and medicine. Yeast, a perfect fungus, uses asexual budding to ferment sugars in brewing and baking, while sexual reproduction is harnessed in genetic studies to create new strains with desirable traits. Understanding these mechanisms can also aid in combating fungal pathogens. For instance, targeting the asexual reproductive cycle of *Candida albicans*, a common human pathogen, could limit its spread in immunocompromised individuals. Conversely, disrupting its sexual cycle might reduce the emergence of drug-resistant strains.

In conclusion, perfect fungi exemplify evolutionary ingenuity, leveraging both sexual and asexual reproduction to thrive in varying environments. Their ability to adapt reproductive strategies based on conditions underscores their ecological importance and practical utility. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into fungal resilience and develop strategies to harness or control their growth, whether in biotechnology or disease management. The dual reproductive systems of perfect fungi are not just a biological curiosity but a key to their success—and ours.

Glutaraldehyde's Effectiveness: Can It Eliminate Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Imperfect Fungi: Lack sexual reproduction, relying solely on asexual spores for propagation and spread

Fungi are remarkably diverse in their reproductive strategies, yet some, known as imperfect fungi, stand out for their reliance on asexual spores alone. Unlike their counterparts that employ both sexual and asexual methods, these fungi lack the genetic recombination that sexual reproduction offers. This limitation might seem like a disadvantage, but it’s a testament to their adaptability. Imperfect fungi, such as those in the genus *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*, thrive in various environments, from soil to food products, by producing vast quantities of asexual spores called conidia. These spores are lightweight, easily dispersed by air or water, and capable of colonizing new habitats rapidly.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus fumigatus*, a common imperfect fungus. When conditions are favorable, it develops conidiophores—specialized structures that bear conidia. A single colony can produce millions of these spores daily, ensuring widespread propagation. This efficiency is particularly evident in indoor environments, where *A. fumigatus* often colonizes damp areas like air conditioning systems or decaying organic matter. For homeowners, this highlights the importance of controlling moisture levels to prevent fungal growth. Practical tips include fixing leaks promptly, using dehumidifiers in humid climates, and ensuring proper ventilation in basements and bathrooms.

The asexual nature of imperfect fungi also has implications for human health. While many are harmless or even beneficial (think of *Penicillium* in antibiotic production), others can cause infections, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores, ubiquitous in the environment, can lead to aspergillosis when inhaled by those with weakened immune systems. To mitigate risks, healthcare providers often recommend HEPA filters for indoor air purification and regular cleaning of HVAC systems. Additionally, individuals undergoing immunosuppressive therapies should avoid environments with visible mold growth.

Comparatively, the absence of sexual reproduction in imperfect fungi limits their ability to adapt to environmental changes through genetic diversity. However, their rapid asexual reproduction compensates by allowing them to exploit resources quickly. This trade-off is evident in agricultural settings, where imperfect fungi like *Fusarium* can cause crop diseases by producing mycotoxins harmful to plants and humans. Farmers can reduce the risk by rotating crops, using fungicides judiciously, and removing infected plant debris. For home gardeners, this translates to practices like spacing plants to improve air circulation and avoiding overwatering.

In conclusion, imperfect fungi exemplify a specialized reproductive strategy that prioritizes speed and efficiency over genetic diversity. Their reliance on asexual spores makes them both prolific colonizers and potential threats in certain contexts. Understanding their lifecycle and environmental preferences empowers individuals to manage their presence effectively, whether in homes, healthcare settings, or agricultural fields. By adopting preventive measures, we can coexist with these fungi while minimizing their negative impacts.

Can Your Mac Run Spore? Compatibility Guide and Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungi produce spores through specialized structures like sporangia, asci, or basidia, depending on the species. Spores are formed via asexual (mitosis) or sexual (meiosis) processes and are released into the environment to disperse and colonize new habitats.

Fungi have two primary reproductive systems: asexual reproduction, which involves the production of spores (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores) without the fusion of gametes, and sexual reproduction, which involves the fusion of haploid cells (gametes) to form a diploid zygote, followed by meiosis to produce spores (e.g., asci spores, basidiospores).

Fungi use asexual reproduction for rapid proliferation in favorable conditions, ensuring quick colonization. Sexual reproduction allows genetic diversity through recombination, which helps fungi adapt to changing environments and survive harsh conditions. Both systems enhance their survival and evolutionary success.