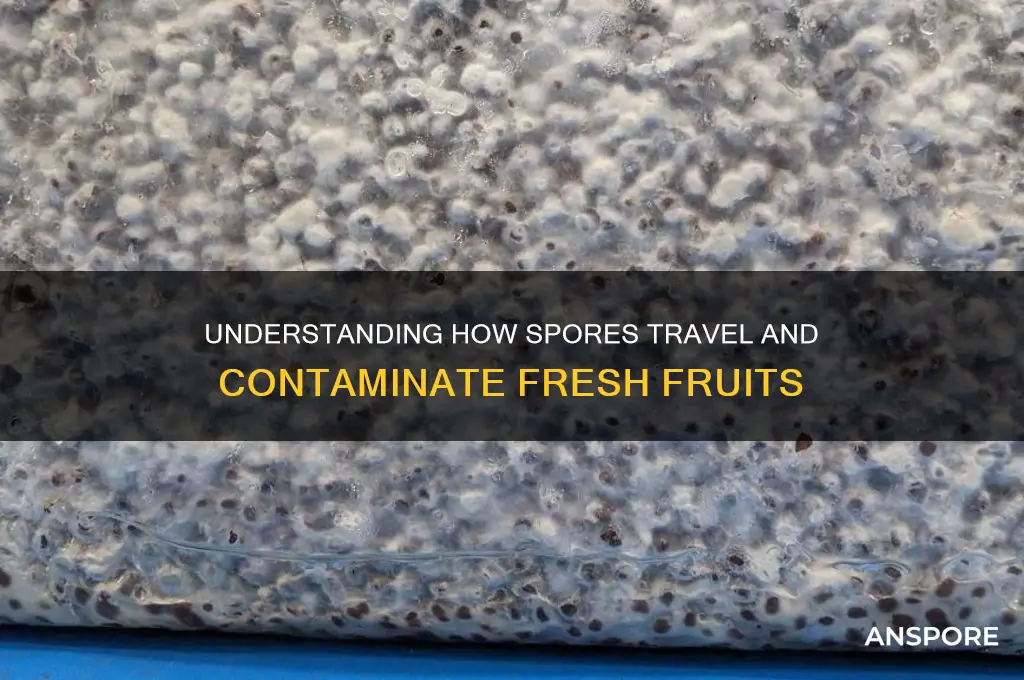

Spores can land on fruit through various means, primarily via air dispersal, as many fungi and bacteria release lightweight spores that travel long distances on wind currents. Once airborne, these spores can settle on fruit surfaces, especially in environments with high humidity or dense vegetation, which facilitate their spread. Additionally, insects, animals, and human handling can inadvertently transfer spores from contaminated sources to fruit, while water splashes from rain or irrigation may carry spores from soil or decaying organic matter onto the fruit’s surface. Proximity to infected plants or fallen fruit also increases the likelihood of spore transmission, making orchards and gardens particularly susceptible to spore colonization on fruit.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Air dispersal (wind, air currents) |

| Secondary Mechanisms | Water splash, insects, animals, human handling, contaminated tools |

| Spores Sources | Soil, decaying plant matter, nearby infected plants, air |

| Favorable Conditions | High humidity, warm temperatures, wet surfaces |

| Common Spores | Fungi (e.g., Botrytis, Penicillium), bacteria, some molds |

| Fruit Susceptibility | Ripe or damaged fruit is more susceptible |

| Prevention Methods | Sanitation, fungicides, proper ventilation, avoiding overcrowding |

| Impact on Fruit | Decay, rot, reduced shelf life, economic losses |

| Detection | Visual inspection, laboratory testing |

| Environmental Factors | Proximity to spore sources, weather conditions, orchard management |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Insects and Animals: Spores can be carried by insects or animals that come into contact with fruit

- Airborne Transmission: Spores can travel through the air and land on fruit surfaces

- Water Splash: Rain or irrigation water can splash spores onto fruit from nearby plants

- Human Handling: People handling fruit can transfer spores from their hands or clothing

- Soil Contamination: Spores in the soil can be kicked up and settle on low-hanging fruit

Insects and Animals: Spores can be carried by insects or animals that come into contact with fruit

Insects and animals play a significant role in the dispersal of spores onto fruit, acting as unwitting carriers in the intricate dance of nature. This process, often overlooked, is a fascinating interplay of biology and ecology. When an insect, such as a bee or a fly, visits a flowering plant to feed on nectar, it may inadvertently come into contact with fungal spores present on the plant's surface. These spores, lightweight and easily dislodged, can attach themselves to the insect's body, particularly its legs, wings, or antennae. As the insect moves on to visit other plants, including fruit-bearing ones, it transfers these spores, facilitating their spread.

Consider the lifecycle of a common fruit fly (*Drosophila melanogaster*). Attracted to ripe or decaying fruit, these flies lay their eggs on the fruit's surface. During this process, if the fruit or its surroundings are contaminated with fungal spores, the flies can pick up these spores on their bodies. When they move to another fruit, they deposit not only their eggs but also the spores, creating a conducive environment for fungal growth. This is particularly concerning in agricultural settings, where an infestation of fruit flies can lead to rapid spore dissemination across a crop, potentially leading to widespread fungal infections like gray mold (*Botrytis cinerea*) or powdery mildew.

To mitigate this, farmers and gardeners can implement several strategies. Firstly, maintaining good hygiene by regularly removing fallen or decaying fruit can reduce the attraction of insects like fruit flies. Secondly, using physical barriers such as fine mesh nets can prevent insects from accessing the fruit. For those who prefer organic methods, introducing natural predators like parasitic wasps (*Aphidius* spp.) can help control fruit fly populations. Additionally, applying organic fungicides, such as those containing potassium bicarbonate or neem oil, can inhibit spore germination and growth. These measures, when applied consistently, can significantly reduce the risk of spore transmission by insects.

A comparative analysis of different animals reveals that larger creatures, such as birds and mammals, can also contribute to spore dispersal, though their impact is often less direct. Birds, for instance, may carry spores on their feathers or feet after perching on infected plants. Similarly, mammals like rodents or bats can transport spores on their fur when they feed on or move through contaminated areas. While these larger animals may not be as efficient as insects in spreading spores to fruit, their mobility allows them to carry spores over greater distances, potentially introducing pathogens to new areas.

In conclusion, understanding the role of insects and animals in spore dispersal is crucial for effective fruit protection. By recognizing the behaviors and lifecycles of these carriers, we can develop targeted strategies to minimize spore contamination. Whether through physical barriers, biological controls, or hygienic practices, proactive measures can help safeguard fruit crops from fungal diseases, ensuring healthier yields and reducing economic losses. This knowledge not only enhances agricultural productivity but also deepens our appreciation for the complex relationships within ecosystems.

Are Spore Servers Down? Current Status and Player Concerns

You may want to see also

Airborne Transmission: Spores can travel through the air and land on fruit surfaces

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, are remarkably resilient and can remain suspended in air for extended periods. This airborne capability allows them to travel significant distances, often carried by wind currents or human activity. When these spores encounter fruit surfaces, they can adhere and, under favorable conditions, germinate, leading to fungal growth and potential decay. Understanding this process is crucial for farmers, distributors, and consumers aiming to mitigate post-harvest losses and ensure fruit quality.

Consider the lifecycle of a spore: once released from a mature fungus, it becomes part of the ambient air, mingling with dust and other particles. Wind, fans, or even the simple act of walking through an orchard can disturb these spores, propelling them toward nearby fruit. The surface of a fruit, often slightly moist and nutrient-rich, provides an ideal landing site. For instance, apples in an orchard are particularly susceptible during humid weather, as moisture on their skin facilitates spore adhesion. Studies show that a single cubic meter of air in an orchard can contain up to 10,000 fungal spores, highlighting the constant threat of airborne transmission.

To combat this, practical measures can be implemented. In agricultural settings, spacing plants adequately improves air circulation, reducing spore concentration around fruits. Additionally, using windbreaks strategically can minimize the influx of spores from external sources. For home gardeners, covering fruit trees with fine mesh netting during peak spore seasons (often late summer to early fall) can significantly reduce spore deposition. However, caution must be exercised to ensure the netting does not trap moisture, which could exacerbate fungal growth.

Comparatively, indoor environments, such as storage facilities, pose a different challenge. Here, spores are often recirculated through HVAC systems, increasing the likelihood of repeated exposure. Installing HEPA filters in ventilation systems can trap spores, reducing their presence in the air. For small-scale storage, such as home refrigerators, wiping fruit surfaces with a mild vinegar solution (1 part vinegar to 3 parts water) before storage can disrupt spore adhesion, though this method is less effective against deeply embedded spores.

In conclusion, airborne transmission of spores is a pervasive yet often overlooked pathway for fruit contamination. By recognizing the mechanisms behind spore travel and implementing targeted interventions, it is possible to significantly reduce the risk of fungal infections. Whether in large-scale agriculture or home gardens, proactive measures tailored to specific environments can preserve fruit quality and extend shelf life, ultimately benefiting both producers and consumers.

Does Spore Work on Gholdengo? Exploring Pokémon Type Matchups

You may want to see also

Water Splash: Rain or irrigation water can splash spores onto fruit from nearby plants

Rain and irrigation water act as unintentional couriers, carrying spores from infected plants and depositing them onto healthy fruit. This process, known as water splash, is a significant contributor to the spread of fungal diseases in orchards and gardens. When raindrops or irrigation droplets strike the surface of an infected leaf or fruit, they dislodge microscopic spores, propelling them into the air. These spores, lightweight and easily airborne, can travel several feet before settling on nearby fruit, where they germinate and initiate new infections.

Understanding the Mechanism: Imagine a scenario where a single apple tree in an orchard is infected with apple scab, a common fungal disease. During a heavy rain, water droplets hitting the infected leaves dislodge spores, creating a spore-laden mist. These spores, carried by the wind and water, land on healthy apples, where they find a suitable environment to grow and multiply. Within days, the once-healthy apples develop dark, scab-like lesions, marking the beginning of a new infection cycle.

Practical Implications and Prevention: To minimize the impact of water splash, consider implementing a few strategic practices. First, maintain adequate spacing between plants to reduce the likelihood of spores traveling from infected to healthy plants. Second, use drip irrigation or soaker hoses instead of overhead sprinklers, as these methods minimize water splash and reduce spore dispersal. If overhead irrigation is necessary, schedule it during the early morning hours to allow foliage to dry quickly, limiting the time spores have to germinate.

Comparative Analysis: Water splash is not limited to rain or irrigation; it can also occur during watering with a garden hose or even from dew evaporation. However, the force and volume of water from rain or irrigation systems make them more efficient spore carriers. For instance, a study found that a single rain event could increase spore dispersal by up to 50% compared to calm, dry conditions. This highlights the importance of managing water application methods to control disease spread.

Takeaway and Actionable Tips: To protect your fruit from water-borne spores, adopt a proactive approach. Regularly inspect plants for signs of disease and promptly remove infected leaves or fruit to reduce spore sources. Apply fungicides preventatively, especially during wet seasons, but always follow label instructions to avoid overuse. For organic growers, consider using biological controls like beneficial bacteria or fungi that compete with pathogens. By understanding and mitigating the role of water splash, you can significantly reduce the incidence of fungal diseases and ensure a healthier, more productive harvest.

Can Your Vacuum Harbor Ringworm Spores? Uncovering the Hidden Risks

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Human Handling: People handling fruit can transfer spores from their hands or clothing

Spores are microscopic and ubiquitous, making them easy to overlook as a contamination source. Human hands, for instance, can carry up to 3,000 bacteria per square inch, and clothing can harbor mold spores from the environment. When people handle fruit, these spores can be transferred, leading to decay or disease. This is particularly problematic in industries like agriculture and food packaging, where multiple hands touch produce before it reaches consumers. Understanding this risk is the first step in mitigating it.

To minimize spore transfer, consider implementing a strict hand hygiene protocol for anyone handling fruit. The CDC recommends washing hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, or using a hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol. For workers in fruit packing facilities, wearing disposable gloves can provide an additional barrier, but gloves should be changed frequently to avoid cross-contamination. Clothing should also be laundered regularly, as spores can cling to fabric fibers. These simple measures can significantly reduce the risk of spore transfer.

A comparative analysis of spore transfer rates reveals that bare hands transfer spores more readily than gloved hands, especially when hands are not washed properly. For example, a study in the *Journal of Food Protection* found that unwashed hands transferred 10 times more spores than gloved hands. However, gloves are not a perfect solution, as they can create a false sense of security and may not be changed as often as needed. The key takeaway is that both hand hygiene and the use of gloves play critical roles in reducing spore contamination.

Practical tips for consumers include washing fruit thoroughly before consumption, even if it appears clean. A solution of one part vinegar to three parts water can be used to wash produce, as vinegar has antimicrobial properties that can help kill spores. For organic fruit, a gentle scrub with a produce brush can remove spores from the surface. Additionally, storing fruit in a clean, dry environment can prevent spore germination. By adopting these practices, individuals can protect themselves and their families from potential health risks associated with spore contamination.

In conclusion, human handling is a significant but often overlooked pathway for spore transfer onto fruit. By focusing on hand hygiene, proper clothing management, and practical cleaning techniques, both industry workers and consumers can reduce the risk of contamination. These measures not only protect the quality and safety of fruit but also contribute to broader food safety goals. Awareness and action are key to breaking the chain of spore transmission.

Do Spores Stain Acid-Fast? Unraveling the Microscopic Mystery

You may want to see also

Soil Contamination: Spores in the soil can be kicked up and settle on low-hanging fruit

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, are ubiquitous in soil, where they lie dormant until conditions favor germination. When soil is disturbed—by wind, rain, human activity, or even the movement of animals—these spores can become airborne. Low-hanging fruit, positioned close to the ground, is particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon. As spores are kicked up into the air, they settle on the surface of the fruit, where they may germinate if moisture and nutrients are present. This process, often overlooked, is a significant pathway for fungal contamination in agriculture.

Consider the lifecycle of a spore: it thrives in organic matter, such as soil, where it remains until it can disperse. A single gram of soil can contain thousands of spores, making it a potent reservoir for fungal pathogens like *Botrytis cinerea* or *Penicillium* species. When a gust of wind sweeps through an orchard or a farmer tills the soil, these spores are dislodged and carried upward. Fruit hanging within a foot of the ground is at highest risk, as spores lose momentum quickly and settle on nearby surfaces. For example, strawberries grown in raised beds are less likely to be contaminated than those grown directly in the soil, simply due to their distance from the spore source.

Preventing spore contamination requires a proactive approach. One practical strategy is to create a physical barrier between the soil and the fruit. Mulching with straw or plastic sheeting can reduce spore dispersal by minimizing soil disturbance. Additionally, pruning plants to ensure fruit grows at a higher elevation can decrease exposure. For farmers, timing is critical: avoid tilling or harvesting during windy conditions, as this exacerbates spore movement. Post-harvest, washing fruit with a dilute chlorine solution (50–200 ppm) can reduce spore viability, though this must be balanced with food safety regulations and product quality.

Comparatively, organic farmers face unique challenges in managing soil-borne spores. Without synthetic fungicides, they rely on cultural practices like crop rotation and compost tea applications to suppress fungal populations. However, these methods are less immediate than chemical interventions, making prevention even more crucial. For instance, planting spore-resistant varieties or using biocontrol agents like *Trichoderma* can reduce the risk of contamination. While these strategies require more planning, they align with sustainable agriculture goals and can yield long-term benefits.

Ultimately, understanding the mechanics of spore dispersal from soil to fruit empowers growers to mitigate risks effectively. By focusing on distance, barriers, and timing, even small-scale farmers can minimize contamination. For consumers, awareness of this pathway highlights the importance of thorough washing before consumption. Whether through preventive measures in the field or careful handling in the kitchen, addressing soil contamination is a critical step in ensuring fruit safety and quality.

Kroot and Ork Symbiosis: Do Kroot Produce Spores After Consuming Orks?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores can land on fruit through various means, including wind, water splashes, insects, or even human handling. They are lightweight and easily dispersed in the environment, making it common for them to settle on fruit surfaces.

Yes, spores from infected plants, weeds, or soil can spread to fruit via air currents, rain, or irrigation water. Proximity to infected vegetation increases the likelihood of spore transfer.

Absolutely. Insects like flies, bees, and other pollinators can carry spores on their bodies as they move from plant to plant, inadvertently depositing them on fruit surfaces.

Yes, spores can remain dormant on fruit surfaces after harvest, especially in favorable conditions like high humidity or warmth. Once conditions are right, they can germinate and cause decay or disease.