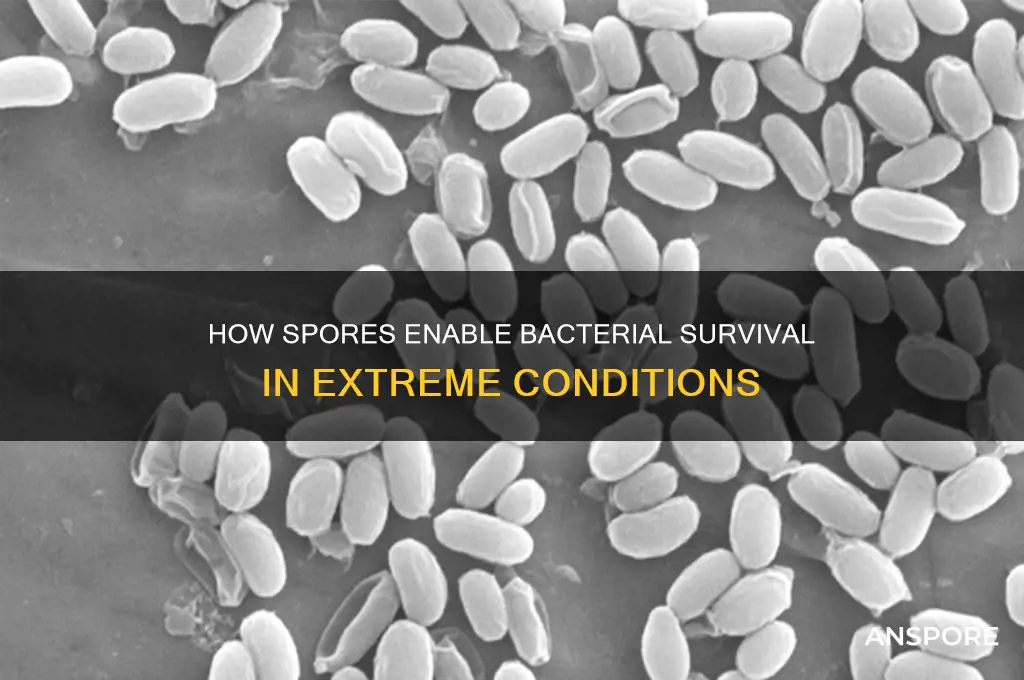

Spores are a crucial survival mechanism for certain bacteria, enabling them to endure harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals or radiation. When faced with unfavorable conditions, these bacteria undergo a process called sporulation, transforming into highly resistant spore forms. Spores have a thick, protective outer layer and minimal metabolic activity, allowing them to remain dormant for extended periods until conditions improve. This resilience ensures bacterial survival in environments where vegetative cells would perish, making spores essential for the long-term persistence and dispersal of bacterial species.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Resistance to Extreme Conditions | Spores can withstand high temperatures, desiccation (drying), radiation, and harsh chemicals, allowing bacteria to survive in environments that would kill their vegetative forms. |

| Metabolic Inactivity | Spores are metabolically dormant, reducing energy consumption and enabling long-term survival in nutrient-poor conditions. |

| Thick Protective Coat | Spores have a multilayered, impermeable outer coat (exosporium, spore coat, and cortex) that protects the genetic material from damage. |

| DNA Protection | Spores contain high levels of calcium-dipicolinic acid (Ca-DPA) and SASP (small acid-soluble spore proteins), which stabilize and protect DNA from degradation. |

| Longevity | Spores can remain viable for years or even centuries, ensuring bacterial survival across generations and adverse conditions. |

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by air, water, or vectors, aiding in colonization of new environments. |

| Rapid Germination | When conditions become favorable, spores can quickly germinate and revert to the vegetative, actively growing form of the bacterium. |

| Resistance to Antibiotics | Spores are highly resistant to most antibiotics, which target active metabolic processes, making them challenging to eradicate. |

| Environmental Persistence | Spores can persist in soil, water, and other environments, serving as a reservoir for bacterial populations. |

| Genetic Stability | The dormant state of spores minimizes mutations, preserving genetic integrity over extended periods. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Bacteria form spores in harsh conditions to protect DNA and ensure survival

- Dormancy: Spores remain dormant for years, resisting extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals

- Dispersal: Spores are lightweight, aiding wind or water dispersal to new environments

- Resistance Mechanisms: Spores have thick walls and repair enzymes to withstand environmental stresses

- Germination: Spores activate and grow into bacteria when conditions become favorable again

Spore Formation: Bacteria form spores in harsh conditions to protect DNA and ensure survival

Bacteria, when faced with harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, or nutrient depletion, employ a remarkable survival strategy: spore formation. This process involves the transformation of a vegetative bacterial cell into a highly resistant spore, a dormant structure designed to protect the organism's genetic material. The primary goal is to safeguard the DNA, ensuring that the bacterium can endure until more favorable conditions return. Spore formation is a complex, energy-intensive process, but it is a critical mechanism for long-term survival in unpredictable environments.

Consider the lifecycle of *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied spore-forming bacterium. When nutrients become scarce, this bacterium initiates a series of genetic and morphological changes. The cell divides asymmetrically, producing a smaller forespore and a larger mother cell. The forespore then undergoes a series of maturation steps, including the synthesis of a thick, protective coat and the dehydration of its cytoplasm. This results in a spore that can withstand conditions that would be lethal to the vegetative form, such as exposure to UV radiation, heat, or chemicals. For instance, spores of *B. subtilis* can survive temperatures up to 100°C for extended periods, a feat impossible for the non-sporulating forms.

The protective properties of spores are not limited to physical durability. The spore’s DNA is encased in a structure called the core, which is highly compacted and protected by proteins like small acid-soluble proteins (SASPs). These proteins bind to the DNA, stabilizing it and preventing damage from reactive oxygen species or other stressors. Additionally, the spore coat acts as a barrier, preventing the entry of harmful substances while maintaining the spore’s internal integrity. This dual-layered protection ensures that the genetic material remains intact, ready to resume growth when conditions improve.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore formation has significant implications for industries such as food safety and healthcare. Spores of bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus cereus* are notorious for surviving food preservation methods such as canning and refrigeration. To mitigate this, food manufacturers use techniques like high-pressure processing or thermal treatments at 121°C for at least 3 minutes to ensure spore destruction. Similarly, in healthcare, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* pose challenges in hospital settings, necessitating rigorous disinfection protocols using spore-specific agents like chlorine bleach.

In conclusion, spore formation is a sophisticated survival mechanism that highlights the resilience of bacteria in the face of adversity. By encapsulating and protecting their DNA, bacteria ensure their genetic continuity across generations, even in the harshest conditions. This process not only underscores the adaptability of microbial life but also provides valuable insights for addressing challenges in food safety, medicine, and environmental science. Understanding spore formation is not just an academic exercise—it’s a practical tool for combating bacterial persistence in real-world scenarios.

Does Mold Release Spores? Understanding Mold Growth and Spread

You may want to see also

Dormancy: Spores remain dormant for years, resisting extreme temperatures, radiation, and chemicals

Spores are nature's time capsules, allowing bacteria to endure conditions that would otherwise spell their demise. This dormancy is not merely a passive state but an active survival strategy honed over millennia. When faced with environmental stresses such as extreme temperatures, radiation, or toxic chemicals, certain bacteria, like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species, transform into spores. These structures are remarkably resilient, with a thick, multi-layered wall that shields the bacterial DNA and enzymes from damage. For instance, spores can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C, doses of UV radiation that would destroy most life forms, and exposure to harsh disinfectants like bleach. This ability to remain dormant for years—even centuries, as evidenced by spores revived from ancient amber—ensures bacterial survival across generations, waiting for conditions to improve before reactivating.

Consider the practical implications of spore dormancy in everyday scenarios. In food preservation, for example, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive boiling temperatures, making it crucial to pressure-cook low-acid foods to reach the 121°C required to destroy them. Similarly, in healthcare settings, spores of *Clostridioides difficile* can persist on surfaces for months, resisting standard cleaning agents. To combat this, facilities must use spore-specific disinfectants like chlorine bleach (5,000–10,000 ppm) or hydrogen peroxide-based cleaners. Understanding spore dormancy also informs strategies in biotechnology, where spores are used as robust vehicles for delivering enzymes or vaccines, leveraging their stability under extreme conditions.

The mechanism behind spore dormancy is a marvel of biological engineering. During sporulation, the bacterium dehydrates its core, reduces metabolic activity to near-zero, and synthesizes protective compounds like dipicolinic acid (DPA). DPA binds calcium ions to form a lattice that stabilizes the spore's DNA and proteins, preventing damage from heat, desiccation, and radiation. This metabolic shutdown allows spores to resist conditions that would denature proteins or fragment DNA in active cells. For example, spores can survive doses of gamma radiation up to 10,000 Gray—enough to kill most organisms—by repairing DNA damage upon reactivation. This resilience makes spores both a challenge in sterilization processes and a model for designing durable biomaterials.

Comparing spore dormancy to other survival strategies highlights its uniqueness. Unlike cysts formed by parasites like *Giardia*, which are less resistant to environmental stresses, bacterial spores are virtually indestructible. Even compared to the hardiest viruses, spores outlast them in terms of longevity and resistance to physical and chemical agents. This superiority stems from the spore's ability to halt all metabolic processes, minimizing the need for energy or repair mechanisms during dormancy. Such adaptability underscores why spore-forming bacteria are among the most widespread and persistent organisms on Earth, from the deepest oceans to the harshest deserts.

For those seeking to control or utilize spore-forming bacteria, understanding dormancy is key. In agriculture, for instance, spores of *Bacillus thuringiensis* are used as biopesticides due to their stability in soil and resistance to degradation. However, their persistence also poses challenges, as spores can contaminate water supplies or food processing equipment. To mitigate risks, industries employ multi-step sterilization methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes, followed by spore-specific disinfectants. Homeowners can protect against spore-forming pathogens like *C. difficile* by using bleach solutions (1:10 dilution) for surface cleaning and ensuring proper hand hygiene. By respecting the tenacity of spores, we can harness their benefits while minimizing their hazards.

Exploring the Rarity of Blue Spore Prints in Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Dispersal: Spores are lightweight, aiding wind or water dispersal to new environments

Spores, by virtue of their lightweight structure, are nature’s solution to bacterial colonization across vast distances. Weighing mere nanograms, these dormant forms of bacteria can be carried by the slightest breeze or water current, reaching environments far beyond their origin. This dispersal mechanism is critical for species survival, as it allows bacteria to escape unfavorable conditions and establish colonies in nutrient-rich habitats. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* spores, known for their resilience, can travel kilometers in dust storms, ensuring the bacterium’s persistence in diverse ecosystems.

Consider the practical implications of spore dispersal in agriculture. Farmers often face soil-borne pathogens that decimate crops. By understanding spore movement, they can implement windbreaks or irrigation management to limit the spread of harmful bacteria like *Clavibacter michiganensis*, which causes tomato canker. Conversely, beneficial spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus subtilis*, can be strategically applied to fields, where their lightweight spores disperse naturally, enhancing soil health and plant growth.

A comparative analysis highlights the efficiency of spore dispersal versus other bacterial survival strategies. While biofilm formation allows bacteria to cling to surfaces, it limits their range. Spores, however, act as microscopic travelers, exploiting environmental forces for global reach. For example, *Deinococcus radiodurans* spores have been found in high-altitude air samples, demonstrating their ability to transcend terrestrial boundaries. This adaptability underscores why spore-forming bacteria are among the most widespread organisms on Earth.

To harness spore dispersal for environmental restoration, follow these steps: First, identify target areas needing bacterial intervention, such as oil-contaminated soil or nutrient-depleted water bodies. Next, select spore-forming bacteria suited to the task, like *Pseudomonas putida* for hydrocarbon degradation. Apply the spores during calm weather to minimize unintended spread, using a sprayer calibrated to disperse 10^6 spores per square meter. Monitor colonization over 4–6 weeks, adjusting application rates as needed. Caution: Ensure the chosen bacteria are non-pathogenic and environmentally safe to avoid ecological disruption.

The takeaway is clear: spore dispersal is a masterclass in biological efficiency, turning environmental forces into tools for survival and propagation. By studying and applying this mechanism, we can combat pathogens, restore ecosystems, and even engineer solutions for space exploration, where lightweight, resilient spores could terraform alien environments. This natural strategy reminds us that sometimes, the smallest packages deliver the most profound impacts.

Are Fungal Spores Airborne? Unveiling the Truth About Their Spread

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Resistance Mechanisms: Spores have thick walls and repair enzymes to withstand environmental stresses

Spores, the dormant forms of certain bacteria, are nature's ultimate survival capsules. Their ability to endure extreme conditions hinges on two key features: thick, protective walls and a suite of repair enzymes. These adaptations allow spores to resist environmental stresses that would destroy most other life forms.

For instance, the spore coat, composed of multiple layers of proteins and peptidoglycan, acts as a formidable barrier against desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. This coat is so resilient that it can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C, making spores a significant concern in food preservation and sterilization processes.

Imagine a scenario where a bacterium faces a harsh environment, such as the arid conditions of a desert or the intense radiation of outer space. In these situations, the bacterium's survival depends on its ability to transform into a spore. The thick spore wall, akin to a suit of armor, shields the bacterial DNA and essential cellular components from damage. This protective layer is not just a passive barrier; it is a complex structure that can repel harmful substances and prevent the entry of destructive agents.

The role of repair enzymes within spores is equally crucial. These enzymes, including DNA repair proteins, are pre-packaged within the spore and become active upon germination. When a spore encounters DNA-damaging agents like UV radiation or toxic chemicals, these enzymes spring into action, repairing the genetic material and ensuring the bacterium's viability. For example, the enzyme UV-endonuclease can repair DNA damage caused by ultraviolet light, a common environmental stressor. This repair mechanism is so efficient that spores can survive for centuries, waiting for favorable conditions to return.

The combination of thick walls and repair enzymes provides spores with a unique advantage in the microbial world. It allows bacteria to persist in environments that would be lethal to their vegetative forms. This survival strategy is particularly evident in species like *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, which can form highly resistant spores. These spores can remain dormant in soil for decades, posing a potential health risk if inhaled or ingested. Understanding these resistance mechanisms is not just academically intriguing; it has practical implications for various fields. In the food industry, for instance, knowing how spores withstand heat and pressure helps in developing more effective sterilization techniques. Similarly, in healthcare, comprehending spore resistance is crucial for designing better disinfection protocols and combating spore-forming pathogens.

In summary, the thick walls and repair enzymes of spores are not just passive defenses but active contributors to bacterial survival. These mechanisms enable spores to endure extreme conditions, ensuring the long-term persistence of certain bacterial species. By studying these adaptations, we gain valuable insights into microbial resilience and can develop strategies to control and utilize spore-forming bacteria in various applications.

Does Grassy Terrain Halt Spore Spread? Exploring the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Germination: Spores activate and grow into bacteria when conditions become favorable again

Spores are nature's time capsules, allowing bacteria to endure harsh environments by entering a dormant state. When conditions improve, these resilient structures spring back to life through germination, a process that transforms them into active, multiplying bacteria. This mechanism is crucial for bacterial survival, ensuring their persistence across adverse conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical exposure.

The Germination Process: A Step-by-Step Awakening

Germination begins when environmental cues signal safety and resource availability. These cues include factors like temperature shifts (often 25–37°C for many species), nutrient presence, and pH changes. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores require specific nutrients like amino acids and purine nucleosides to initiate germination. Once triggered, the spore’s protective coat softens, allowing water uptake. This rehydration activates enzymes like hydrolytic enzymes, which break down stored nutrients, providing energy for DNA repair and metabolic restart. Within minutes to hours, the spore swells, sheds its protective layers, and emerges as a vegetative cell ready to grow and divide.

Comparative Advantage: Why Germination Matters

Unlike vegetative cells, which perish under stress, spores can remain viable for decades or even centuries. For example, *Clostridium botulinum* spores have been found in sediments over 10,000 years old, only to germinate when conditions permit. This longevity gives bacteria a competitive edge, ensuring their survival in unpredictable environments. Germination is not just a return to life; it’s a strategic response to opportunity, allowing bacteria to recolonize habitats swiftly when competitors may still be dormant or absent.

Practical Implications: Controlling Germination in Real-World Scenarios

Understanding germination is vital for industries like food safety and medicine. In food preservation, preventing spore germination is key to avoiding contamination. Techniques such as pasteurization (heating to 72°C for 15 seconds) or adding nitrites to cured meats inhibit germination. Conversely, in biotechnology, controlled germination is used to produce probiotics or enzymes. For instance, *Bacillus* spores are activated in soil remediation to degrade pollutants efficiently. Home gardeners can exploit this by using spore-based inoculants to enhance plant growth, ensuring application during warm, moist conditions for optimal germination.

Cautions and Challenges: When Germination Turns Hazardous

While germination is a survival tool for bacteria, it poses risks when harmful species activate. *Clostridium difficile* spores, for example, germinate in the gut after antibiotic use, leading to severe infections. Similarly, *Anthrax* spores can germinate in mammalian hosts, causing lethal disease. Preventing unintended germination requires vigilance in healthcare settings, such as thorough disinfection of medical equipment and isolating patients with spore-forming pathogens. Even in research labs, handling spores demands strict protocols, including HEPA filtration and autoclaving, to avoid accidental activation and spread.

By mastering the intricacies of germination, we can harness its benefits while mitigating its dangers, ensuring that this remarkable process serves life rather than threatens it.

Do Spores Move? Unveiling the Surprising Truth About Their Mobility

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are highly resistant structures formed by certain bacteria, such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, in response to unfavorable conditions like nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation. They contain minimal water, have thick protective coats, and repair DNA damage, allowing bacteria to remain dormant until conditions improve.

Yes, bacterial spores can survive for years, even decades, in the absence of nutrients and water. Their dormant state and robust protective layers enable them to withstand extreme environments, including heat, radiation, and chemicals, until they encounter conditions suitable for growth.

Spores are lightweight and easily carried by air, water, or other vectors, facilitating bacterial dispersal over long distances. Once they reach a favorable environment, spores germinate into active bacterial cells, allowing the species to colonize new habitats and ensure survival.

![Formation of Spores in the Sporanges of Rhizopus Nigricans / by Deane Bret Swingle 1901 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)