Spores play a crucial role in sustaining fern populations by serving as their primary means of reproduction and dispersal. Unlike flowering plants that rely on seeds, ferns produce tiny, lightweight spores that can be carried by wind or water over long distances, allowing them to colonize new habitats. These spores develop into small, heart-shaped structures called prothalli, which are the fern's gametophyte stage. Prothalli produce both eggs and sperm, enabling sexual reproduction even in the absence of water nearby, as they can retain moisture in humid environments. This adaptability ensures ferns can thrive in diverse ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands, making spores essential for their survival and propagation across generations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Dispersal Mechanism | Spores are lightweight and can be carried by wind, water, or animals over long distances, allowing ferns to colonize new habitats. |

| Survival in Adverse Conditions | Spores can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh environmental conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, or lack of suitable substrate. |

| Genetic Diversity | Spores are produced through meiosis, leading to genetic recombination and increased genetic diversity, which enhances the species' adaptability to changing environments. |

| Rapid Reproduction | Ferns can produce a large number of spores quickly, enabling rapid population growth and recovery after disturbances. |

| Asexual Reproduction | Spores can develop into gametophytes, which can produce new fern plants without the need for fertilization, ensuring population sustainability even in the absence of mates. |

| Low Resource Requirement | Spores require minimal resources to develop into gametophytes, making them efficient for colonization in nutrient-poor environments. |

| Longevity | Spores have a long shelf life, allowing them to persist in the environment until conditions are favorable for germination and growth. |

| Adaptability to Microhabitats | Spores can settle and grow in diverse microhabitats, increasing the chances of successful establishment and population expansion. |

| Resistance to Predators | Spores are less susceptible to predation compared to seeds, ensuring higher survival rates during dispersal. |

| Role in Ecosystem | Spores contribute to soil health and ecosystem dynamics by decomposing and releasing nutrients, supporting the overall sustainability of fern populations and their habitats. |

Explore related products

$27.99

What You'll Learn

- Spore Production: Ferns release spores in large numbers, increasing chances of survival and colonization

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals aid spore spread, reaching diverse habitats for growth

- Dormancy Advantage: Spores remain dormant, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments emerge

- Genetic Diversity: Spores from different ferns mix, promoting genetic variation and adaptability

- Efficient Reproduction: Spores require minimal resources, ensuring widespread reproduction with low energy investment

Spore Production: Ferns release spores in large numbers, increasing chances of survival and colonization

Ferns employ a reproductive strategy centered on the mass release of spores, a tactic that significantly enhances their survival and colonization potential. Unlike seeds, which contain embryonic plants and nutrient stores, spores are single-celled and lightweight, allowing them to travel vast distances via wind or water. This dispersal mechanism is crucial for ferns, which often inhabit shaded, competitive environments where establishing new colonies is challenging. By producing thousands to millions of spores per fertile frond, ferns maximize the likelihood that at least some will land in suitable habitats, germinate, and grow into new individuals.

Consider the mathematics of spore production: a single fern can release up to 10,000 spores per sporangium, with hundreds of sporangia on each fertile frond. This results in millions of spores per plant during a single reproductive cycle. While the majority of these spores may fail to survive due to harsh conditions, predation, or unsuitable landing sites, the sheer volume ensures that a small fraction will find favorable environments. For example, in dense forests where light is limited, spores that land in small clearings or along forest edges have a higher chance of developing into gametophytes, the next stage in the fern life cycle.

The efficiency of spore production is further amplified by the fern’s ability to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from tropical rainforests to temperate woodlands. Spores’ minimal resource requirements allow them to remain dormant for extended periods, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This adaptability is particularly advantageous in unpredictable environments, such as floodplains or disturbed areas, where ferns can quickly colonize newly available spaces. For gardeners or conservationists, encouraging spore production in ferns can be as simple as ensuring adequate moisture, light, and air circulation, which promotes the development of fertile fronds.

A comparative analysis highlights the superiority of spore production over other reproductive methods in ferns’ ecological niche. While flowering plants rely on pollinators and seed dispersers, ferns bypass these dependencies by dispersing spores directly into the environment. This independence reduces vulnerability to disruptions in pollinator populations or seed predators. Additionally, the microscopic size of spores allows them to exploit microhabitats inaccessible to larger seeds, such as cracks in rocks or thin layers of soil on tree trunks. This versatility underscores why spore production is a cornerstone of fern population sustainability.

In practical terms, understanding spore production can guide efforts to cultivate or conserve ferns. For instance, propagating ferns in a garden setting involves collecting mature fronds with visible spore cases (sori) and placing them in a paper bag to capture released spores. These spores can then be sown on a moist substrate, such as a mix of peat and sand, and kept in a humid environment to encourage germination. By mimicking natural conditions, enthusiasts can witness the entire fern life cycle, from spore to sporophyte, while contributing to the species’ continued proliferation. This hands-on approach not only fosters appreciation for ferns’ reproductive strategy but also highlights the critical role of spore production in their ecological success.

Sunlight's Power: Can It Eliminate C. Diff Spores Effectively?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals aid spore spread, reaching diverse habitats for growth

Ferns, ancient plants with a lineage stretching back millions of years, rely on spores for their survival and propagation. Unlike seeds, spores are microscopic, lightweight, and produced in vast quantities, making them ideal for dispersal over long distances. This dispersal is crucial for ferns to colonize new habitats, avoid competition, and ensure genetic diversity. Wind, water, and animals act as the primary agents in this process, each playing a unique role in spreading spores far and wide.

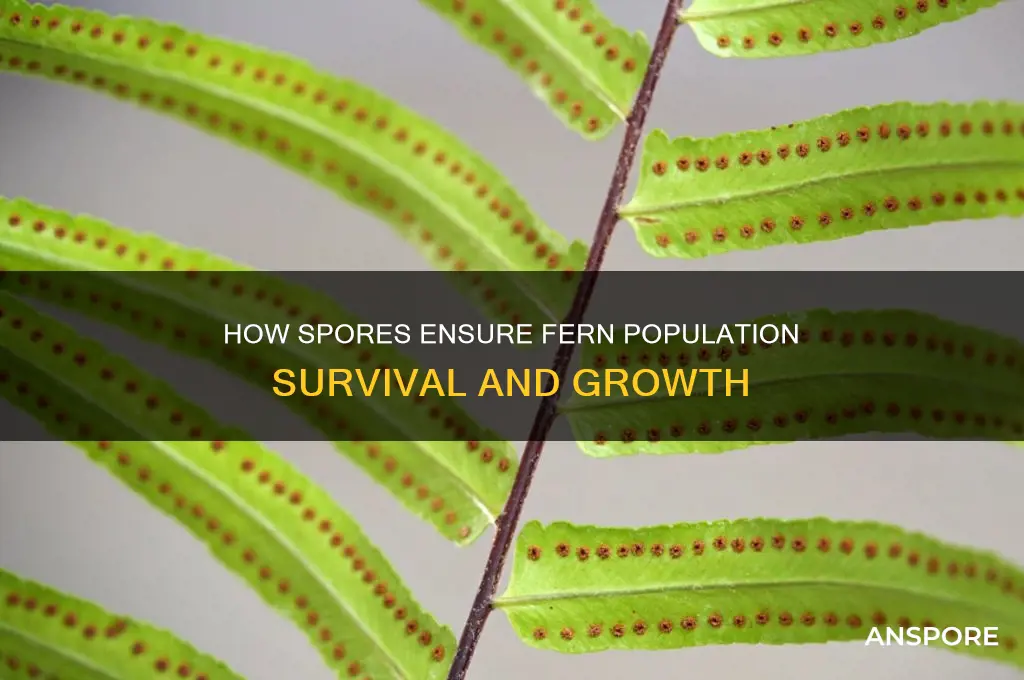

Wind dispersal is perhaps the most common mechanism for fern spores. Ferns often produce spore cases, or sporangia, on the undersides of their fronds, strategically positioned to catch the breeze. When mature, these sporangia release spores that are carried aloft by even the gentlest winds. The lightweight nature of spores allows them to travel significant distances, sometimes even crossing geographical barriers like rivers or mountains. For instance, the *Pteris vittata* fern, commonly known as the brake fern, has been observed to disperse spores over several kilometers in open landscapes. To maximize wind dispersal, gardeners and conservationists can plant ferns in elevated areas or near natural wind corridors, ensuring spores have a clear path to travel.

Water dispersal, while less common than wind, is equally vital for ferns in aquatic or riparian environments. Spores released into water currents can be transported downstream, colonizing new areas along riverbanks or wetlands. The *Ceratopteris thalictroides*, or water sprite fern, is a prime example of a species that thrives in such conditions. Its spores are buoyant and can remain viable in water for extended periods, allowing them to reach distant habitats. For those cultivating ferns near water bodies, ensuring a gentle flow of water around the plants can enhance spore dispersal. However, care must be taken to avoid excessive water movement, which could damage the delicate fronds.

Animals, though less obvious dispersers, contribute significantly to spore spread through indirect means. Small creatures like insects, birds, and mammals can carry spores on their bodies or fur as they move through fern habitats. For example, a bird perching on a fern may inadvertently pick up spores on its feathers, later depositing them in a new location. Similarly, mammals brushing against fern fronds can transport spores to different areas. While this method is less predictable than wind or water, it plays a crucial role in introducing ferns to microhabitats that might otherwise remain uncolonized. Encouraging biodiversity in fern-rich areas, such as planting companion species that attract wildlife, can enhance this natural dispersal mechanism.

In conclusion, the dispersal of fern spores through wind, water, and animals is a multifaceted process that ensures the survival and expansion of fern populations. Each mechanism has its advantages and limitations, but together they create a robust system for reaching diverse habitats. By understanding these processes, we can better appreciate the resilience of ferns and take practical steps to support their growth, whether in natural ecosystems or cultivated gardens. From planting ferns in strategic locations to fostering biodiversity, every action contributes to the continued success of these ancient plants.

Are Mold Spores Alive? Unveiling the Truth About Fungal Life

You may want to see also

Dormancy Advantage: Spores remain dormant, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments emerge

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of ferns, possess a remarkable ability to enter a state of dormancy, a survival strategy that ensures the longevity and resilience of fern populations. This dormant phase is a critical adaptation, allowing spores to withstand environmental extremes that would otherwise be lethal to the delicate fern life cycle. When conditions turn unfavorable, whether due to drought, extreme temperatures, or nutrient scarcity, spores can suspend their metabolic activities, essentially hitting a pause button on their development.

The mechanism of dormancy is a sophisticated response to environmental cues. As a fern sporophyte matures, it releases spores into the surroundings. These spores are equipped with a tough outer wall, providing a protective barrier against desiccation and physical damage. Upon landing in an inhospitable environment, spores can remain viable for extended periods, sometimes years, until the right combination of moisture, temperature, and light triggers their germination. This waiting game is a strategic move, ensuring that the next generation of ferns emerges when the chances of survival are maximized.

Consider the practical implications of this dormancy advantage. In regions prone to seasonal changes, such as temperate forests, spores released during the fertile summer months can lie dormant throughout the harsh winter. As spring arrives, bringing warmer temperatures and increased rainfall, these dormant spores spring into action, germinating and developing into gametophytes. This timing is crucial, as it synchronizes the fern's life cycle with the availability of resources, increasing the likelihood of successful reproduction and the establishment of new fern populations.

The dormancy period also allows ferns to colonize new habitats and recover from disturbances. For instance, in areas affected by wildfires or deforestation, the soil may be left barren and exposed. Spores, with their ability to remain dormant, can persist in the soil seed bank, waiting for the opportune moment to germinate when the environment becomes conducive to growth. This strategy ensures that ferns can rapidly re-establish themselves, contributing to the regeneration of ecosystems and maintaining their presence in diverse habitats.

Furthermore, the dormancy advantage provides a buffer against the uncertainties of climate change. As global temperatures fluctuate and weather patterns become more erratic, the ability of spores to bide their time becomes increasingly valuable. Ferns, with their ancient lineage, have evolved this mechanism to navigate through geological epochs, and it continues to serve them well in the face of modern environmental challenges. By remaining dormant, spores can outlast periods of adversity, ensuring the continuity of fern species and their contribution to biodiversity.

In essence, the dormancy of spores is a strategic wait-and-see approach, a natural form of insurance against environmental unpredictability. This adaptation not only sustains fern populations through harsh conditions but also enables them to thrive and expand when the environment becomes favorable. Understanding this mechanism offers insights into the resilience of ferns and highlights the importance of preserving their habitats, ensuring that these ancient plants continue to flourish and contribute to the health of ecosystems worldwide.

Do Morel Spore Kits Work? Unveiling the Truth for Mushroom Growers

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Genetic Diversity: Spores from different ferns mix, promoting genetic variation and adaptability

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of ferns, play a pivotal role in sustaining fern populations by facilitating genetic diversity. Unlike seeds, which are produced by the fusion of gametes from a single plant, spores from different ferns can mix and combine, creating new genetic combinations. This process, known as outcrossing, ensures that fern populations are not limited to the genetic material of their parent plants. For instance, when spores from a fern with drought resistance traits combine with those from a fern with pest resistance, the resulting offspring may inherit both advantageous traits, enhancing their survival in diverse environments.

To understand the practical implications, consider the steps involved in spore mixing. Spores are released into the air or water, traveling varying distances before settling in a suitable environment. Once germinated, they develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes (sperm and eggs). When sperm from one fern’s gametophyte fertilizes the egg of another, the genetic material from both parents combines. This mixing is not random but influenced by environmental factors like wind patterns, water flow, and habitat proximity. For example, ferns in dense forests may have limited spore dispersal, while those near rivers can spread spores over greater distances, increasing the likelihood of genetic exchange.

The benefits of this genetic diversity are twofold: adaptability and resilience. In a changing environment, ferns with varied genetic traits are better equipped to survive new challenges, such as temperature fluctuations or disease outbreaks. A study on *Pteridium aquilinum* (bracken fern) revealed that populations with higher genetic diversity exhibited greater resistance to fungal pathogens. Similarly, ferns in fragmented habitats rely on spore mixing to maintain genetic health, preventing inbreeding and the associated risks of reduced fitness. For gardeners or conservationists, encouraging spore dispersal—by planting ferns in open areas or near water sources—can enhance genetic diversity and strengthen fern populations.

However, spore mixing is not without challenges. While it promotes diversity, it also depends on the presence of compatible ferns within a reasonable distance. Urbanization and habitat destruction can limit spore dispersal, reducing genetic exchange. To mitigate this, conservation efforts should focus on creating corridors between fern habitats, allowing spores to travel freely. Additionally, cultivating multiple fern species in gardens or restoration sites can artificially increase the chances of spore mixing, mimicking natural conditions.

In conclusion, the ability of spores from different ferns to mix and combine genetic material is a cornerstone of fern population sustainability. This process not only fosters adaptability but also ensures the long-term resilience of fern communities in the face of environmental changes. By understanding and supporting spore dispersal, we can actively contribute to the preservation of these ancient plants, ensuring their survival for generations to come.

Mushroom Spores and Dogs: Understanding Potential Dangers and Safety Tips

You may want to see also

Efficient Reproduction: Spores require minimal resources, ensuring widespread reproduction with low energy investment

Spores are the unsung heroes of fern reproduction, embodying efficiency in their ability to sustain populations with minimal resource demands. Unlike seeds, which require energy-intensive structures like flowers and fruits, spores are microscopic, lightweight, and produced in vast quantities. This simplicity allows ferns to allocate energy to survival rather than complex reproductive mechanisms, ensuring their persistence in diverse environments.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern: from the sporophyte (adult plant) to the gametophyte (tiny, heart-shaped structure), the process is streamlined. Spores, once released, can travel far on air currents, colonizing new habitats with ease. This dispersal strategy requires no pollinators, no seed dispersal agents, and no parental investment beyond spore production. For ferns in nutrient-poor or disturbed ecosystems, this efficiency is a lifeline, enabling them to thrive where other plants struggle.

To illustrate, imagine a forest floor after a fire. The soil is barren, and resources are scarce. Fern spores, carried by the wind, land and germinate, forming gametophytes that require only moisture and minimal nutrients. These gametophytes then produce the next generation of ferns, all without the energy-intensive processes seen in flowering plants. This low-resource strategy ensures ferns can rapidly recolonize areas, maintaining their population even in challenging conditions.

Practical observation reveals the adaptability of this system. Gardeners cultivating ferns often note their ability to spread naturally, requiring no intervention beyond initial planting. For those looking to propagate ferns, collecting spore-bearing structures (indusia) and scattering them in shaded, moist areas yields results with minimal effort. This hands-off approach mirrors the fern’s natural strategy, proving that efficiency in reproduction is not just a survival mechanism but a practical advantage.

In essence, spores are the epitome of reproductive frugality. By requiring minimal resources and energy, they enable ferns to reproduce widely and persist in environments where other plants falter. This efficiency is not just a biological curiosity but a lesson in sustainability, demonstrating how simplicity can lead to enduring success.

Are Spore Servers Still Active in 2023? A Comprehensive Update

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are the primary means of reproduction for ferns. They are produced in structures called sporangia on the undersides of fern leaves. When released, spores can disperse over long distances via wind or water, allowing ferns to colonize new areas and sustain their population.

Spores are lightweight, numerous, and highly adaptable, enabling ferns to survive in diverse environments. Their small size and ability to remain dormant for extended periods ensure that at least some spores will land in suitable conditions for growth, thus sustaining the fern population.

Spores undergo a process called alternation of generations, where they develop into gametophytes that produce both male and female reproductive cells. This sexual reproduction allows for genetic recombination, increasing diversity and helping fern populations adapt to changing environments.