Spores in plants are a fundamental part of their reproductive cycle, particularly in non-seed plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. Unlike seeds, which contain a developing embryo, spores are single-celled structures that can develop into a new organism under favorable conditions. Plants produce spores through a process called sporulation, which occurs in specialized structures such as sporangia. When released, spores are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing them to travel to new environments. Once a spore lands in a suitable habitat, it germinates, growing into a gametophyte—a small, photosynthetic plant that produces gametes. These gametes then fuse to form a zygote, which develops into a new sporophyte, completing the life cycle. This method of reproduction enables plants to thrive in diverse ecosystems and ensures their survival in challenging conditions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Spores are microscopic, unicellular or multicellular reproductive units produced by plants (and some algae, fungi) for asexual or sexual reproduction. |

| Types | Asexual Spores (Vegetative): Produced by mitosis (e.g., gemmae in liverworts). Sexual Spores: Produced by meiosis (e.g., spores from sporangia in ferns, mosses). |

| Production Site | Formed in specialized structures like sporangia (e.g., fern fiddleheads) or sporophytes (diploid phase in plant life cycles). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Wind, water, animals, or explosive release (e.g., sphagnum moss spores). |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for years in harsh conditions, germinating when favorable conditions return. |

| Germination | Develops into a gametophyte (haploid phase) upon landing in suitable environments, eventually producing gametes for sexual reproduction. |

| Advantages | Lightweight, resistant to extreme conditions, allows rapid colonization of new habitats. |

| Examples | Ferns, mosses, liverworts, lycophytes, and some seedless vascular plants. |

| Comparison to Seeds | Unlike seeds, spores lack stored food and an embryo; they rely on external resources for growth. |

| Ecological Role | Key in plant evolution, survival in diverse ecosystems, and maintaining biodiversity. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation: Spores develop in sporangia via meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in plant reproduction

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals aid spore dispersal, increasing colonization chances

- Germination Process: Spores activate under favorable conditions, growing into gametophytes

- Life Cycle Role: Spores bridge alternation of generations in plant life cycles

- Survival Adaptations: Spores withstand harsh conditions, ensuring long-term species survival

Spore Formation: Spores develop in sporangia via meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in plant reproduction

Spores are the microscopic, resilient units through which many plants, fungi, and some algae reproduce. Unlike seeds, which contain a young embryo, spores are single cells capable of developing into a new organism under favorable conditions. In plants, spore formation is a critical process that ensures genetic diversity and survival across generations. This process occurs within specialized structures called sporangia, where meiosis—a type of cell division—reduces the chromosome number, creating genetically unique spores.

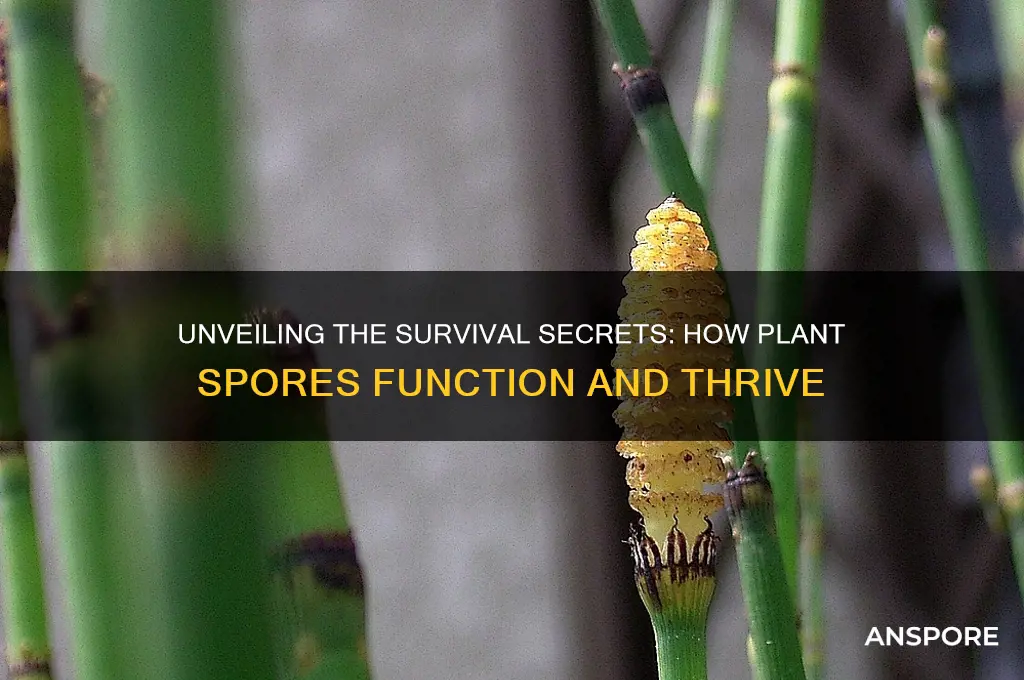

To understand spore formation, consider the life cycle of a fern, a prime example of a spore-producing plant. Ferns alternate between a sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) generation. The sporophyte phase is the dominant, visible plant we recognize. On the underside of its fronds, sporangia cluster into structures called sori. Inside each sporangium, cells undergo meiosis, halving their chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n). This reduction is crucial for genetic diversity, as it allows for the recombination of traits when spores later develop into gametophytes. Each sporangium can produce hundreds of spores, which are then released into the environment, dispersing via wind or water.

The process of meiosis within sporangia is not just a biological mechanism but a survival strategy. By producing genetically diverse spores, plants increase their adaptability to changing environments. For instance, if a population of ferns faces a new disease, some spores may carry traits resistant to it, ensuring the species’ survival. This diversity is particularly vital for plants that cannot relocate, as it provides a buffer against unpredictable conditions. In contrast, plants relying solely on asexual reproduction risk uniformity, making them vulnerable to threats like pests or climate shifts.

Practical observation of spore formation can be a rewarding educational activity. To witness this process, collect a mature fern frond with visible sori and place it on a sheet of white paper overnight. By morning, you’ll see a fine dusting of spores, each a product of meiosis. For a closer look, use a magnifying glass or microscope to examine the sporangia and spores. This hands-on approach not only illustrates the mechanics of spore formation but also highlights the elegance of nature’s solutions to genetic diversity.

In conclusion, spore formation via meiosis in sporangia is a cornerstone of plant reproduction, balancing continuity with adaptability. By producing genetically diverse spores, plants ensure their resilience in the face of environmental challenges. Whether you’re a botanist, educator, or curious observer, understanding this process offers insights into the intricate strategies plants employ to thrive. Next time you see a fern or moss, remember the microscopic drama unfolding within its sporangia—a testament to the ingenuity of life.

Klebsiella Aerogenes: Understanding Its Sporulation Capabilities and Implications

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Wind, water, and animals aid spore dispersal, increasing colonization chances

Spores, the microscopic units of plant reproduction, rely heavily on external forces for dispersal. Wind, water, and animals act as unwitting couriers, carrying these lightweight, resilient structures to new habitats. This passive transport mechanism is crucial for spore-producing plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, which lack the seeds and flowers of more advanced species. Without such dispersal, these plants would remain confined to their immediate surroundings, limiting their ability to colonize diverse environments.

Consider the role of wind, perhaps the most widespread dispersal agent. Spores of plants like ferns and mushrooms are often equipped with features that enhance their aerodynamic properties. For instance, fern spores are typically small and lightweight, allowing them to be carried over long distances by even gentle breezes. In contrast, some fungal spores, like those of puffballs, are released in explosive clouds, maximizing their exposure to air currents. To optimize wind dispersal in your garden, plant spore-producing species in open areas where air movement is unobstructed. Avoid dense vegetation or structures that could block airflow, reducing dispersal efficiency.

Water serves as another vital medium for spore dispersal, particularly in aquatic and semi-aquatic environments. Plants like certain algae and liverworts release spores that can float on water surfaces, drifting to new locations. This method is especially effective in rivers, streams, and ponds, where currents facilitate movement. For example, the spores of the water fern *Azolla* can travel significant distances in calm waters, colonizing new areas with ease. If you’re cultivating water-dispersed spore plants, ensure they have access to flowing or gently moving water to enhance spore distribution. Stagnant water may trap spores, limiting their dispersal range.

Animals, though less obvious as dispersal agents, play a significant role in transporting spores. Spores can adhere to the fur, feathers, or skin of animals as they move through habitats, hitching a ride to distant locations. For instance, the spores of certain fungi and lichens are inadvertently carried by insects, birds, and mammals. Even humans contribute to spore dispersal, as spores cling to clothing and shoes. To encourage animal-mediated dispersal, create habitats that attract wildlife, such as bird feeders or insect-friendly plants. However, be cautious of invasive species; ensure the spores being dispersed are native to your region to avoid ecological disruption.

Each dispersal mechanism—wind, water, and animals—offers unique advantages, increasing the chances of spores reaching suitable habitats for colonization. Wind provides broad coverage, water ensures targeted dispersal in aquatic ecosystems, and animals facilitate access to otherwise inaccessible areas. By understanding these mechanisms, gardeners, ecologists, and enthusiasts can strategically support spore-producing plants, fostering biodiversity and ecological resilience. Whether you’re cultivating a fern garden or studying fungal ecosystems, harnessing these natural forces can amplify the success of spore-based plant reproduction.

Liverwort Spore Capsules: Unveiling Their Unique Reproductive Structures

You may want to see also

Germination Process: Spores activate under favorable conditions, growing into gametophytes

Spores, the microscopic, resilient units produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi, lie dormant until conditions align for growth. This activation, known as germination, is a pivotal phase in the life cycle of spore-producing organisms. When spores encounter the right combination of moisture, temperature, and light, they spring to life, initiating a transformation from a dormant state to an active, growing organism. This process is not merely a random event but a finely tuned response to environmental cues, ensuring survival in diverse ecosystems.

Consider the fern, a prime example of a spore-producing plant. Fern spores, often dispersed by wind, land in various environments, but only those with adequate moisture and shade will germinate. Upon absorption of water, the spore’s protective coat softens, allowing the emergence of a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte. This gametophyte, though small, is a fully functional plant with a critical role: producing gametes for sexual reproduction. The entire process underscores the spore’s adaptability, as it remains viable for years, waiting for the precise conditions to thrive.

The germination process is not uniform across all spore-producing organisms. For instance, fungal spores, such as those of mushrooms, require specific substrates like decaying wood or soil rich in organic matter. In contrast, moss spores prefer bare, moist surfaces like rocks or soil. This diversity highlights the spore’s ability to tailor its activation to the ecological niche of its parent organism. Understanding these preferences is crucial for horticulture, conservation, and even mycology, where controlled environments can mimic these conditions to cultivate specific species.

Practical applications of spore germination extend beyond biology. Gardeners can enhance fern growth by sprinkling spores on damp, shaded soil and maintaining consistent moisture. Similarly, mushroom cultivators use spore syringes to inoculate substrates like straw or wood chips, ensuring optimal conditions for mycelium growth. For educators, demonstrating spore germination under a microscope offers a tangible way to teach plant life cycles. By observing the transition from spore to gametophyte, students grasp the intricate balance between dormancy and growth in nature.

In essence, the germination of spores is a testament to nature’s efficiency and precision. It’s a process that bridges dormancy and life, ensuring the continuity of species across generations. Whether in a forest, garden, or laboratory, the activation of spores under favorable conditions is a microcosm of life’s resilience and adaptability. By studying and replicating these conditions, we not only deepen our understanding of plant biology but also harness this knowledge for practical, real-world applications.

Seeds vs. Spores: Comparing Nature's Dispersal Strategies and Survival Tactics

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Life Cycle Role: Spores bridge alternation of generations in plant life cycles

Spores are the unsung heroes of plant reproduction, serving as the critical link between two distinct phases in the life cycle of many plants. In species that exhibit alternation of generations, such as ferns, mosses, and some algae, spores bridge the gap between the diploid sporophyte generation and the haploid gametophyte generation. This process ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, allowing plants to thrive in diverse environments. Without spores, the transition between these generations would be impossible, disrupting the delicate balance of plant life cycles.

Consider the fern as a prime example. After a mature fern produces spores on the underside of its fronds, these spores are dispersed by wind or water. Each spore develops into a tiny, heart-shaped gametophyte known as a prothallus. This gametophyte is a self-sustaining organism that produces gametes—sperm and eggs. When conditions are right, sperm swim to fertilize the egg, resulting in a new sporophyte. This cycle repeats, with spores acting as the essential intermediary. The beauty of this system lies in its efficiency: spores are lightweight, durable, and capable of surviving harsh conditions, ensuring the continuity of the species.

From an analytical perspective, the role of spores in alternation of generations highlights the evolutionary brilliance of plants. By separating the sporophyte and gametophyte stages, plants maximize their reproductive strategies. The sporophyte, often the more visible and dominant generation, focuses on growth and spore production, while the gametophyte specializes in sexual reproduction. Spores, being haploid, introduce genetic variation through meiosis, which is crucial for adaptation. This division of labor allows plants to exploit different ecological niches, increasing their chances of survival.

For gardeners or enthusiasts looking to observe this process, cultivating ferns or mosses provides a hands-on opportunity. Start by collecting spores from mature plants—fern spores, for instance, can be found in clusters called sori on the underside of leaves. Sprinkle these spores on a moist, sterile medium like peat moss or soil. Keep the environment humid and shaded, as gametophytes require moisture to thrive. Over time, you’ll witness the development of prothalli and, eventually, new sporophytes. This practical exercise not only deepens understanding but also fosters appreciation for the intricate role spores play in plant life cycles.

In conclusion, spores are not merely reproductive units but vital connectors that sustain the alternation of generations in plant life cycles. Their ability to transition between diploid and haploid phases ensures genetic diversity, resilience, and continuity. Whether observed in a fern’s lifecycle or cultivated in a garden, spores exemplify nature’s ingenuity. Understanding their role enriches our knowledge of plant biology and underscores the importance of preserving these microscopic marvels.

Do Kangaroo Ferns Have Spores? Unveiling Their Unique Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Survival Adaptations: Spores withstand harsh conditions, ensuring long-term species survival

Spores are nature's ultimate survival capsules, engineered to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Unlike seeds, which require immediate access to resources to germinate, spores can remain dormant for decades, even centuries, waiting for the perfect moment to activate. This resilience is rooted in their minimalistic design: a tough outer wall, or exine, shields the genetic material inside, while desiccation-tolerant proteins and sugars prevent cellular damage in extreme dryness. For instance, *Selaginella lepidophylla*, a desert plant, produces spores that can survive temperatures ranging from -273°C to 100°C, showcasing their adaptability to both freezing and scorching environments.

Consider the lifecycle of ferns, which rely entirely on spores for reproduction. When released into the wind, these microscopic units can travel vast distances, colonizing barren or disturbed lands where other plants cannot thrive. Once they land in a suitable environment, they can detect subtle cues like moisture levels and light exposure to determine when to sprout. This strategic delay ensures that energy is not wasted in unfavorable conditions, a critical advantage in unpredictable ecosystems. For gardeners attempting to cultivate spore-dependent plants, patience is key—some species may require specific triggers, such as a fire-induced chemical release, to break dormancy.

The survival prowess of spores extends beyond physical durability to include biochemical ingenuity. Many spores produce melanin, a pigment that not only protects against UV radiation but also neutralizes toxic compounds in polluted soils. This adaptation is particularly evident in fungi like *Aspergillus niger*, whose spores thrive in environments contaminated by heavy metals. Similarly, some plant spores secrete antifungal compounds to ward off competitors, ensuring their offspring have a fighting chance in crowded habitats. For researchers studying spore resilience, isolating these protective mechanisms could inspire innovations in preserving human food supplies or developing radiation-resistant materials.

Comparing spore-producing plants to their seed-bearing counterparts highlights the evolutionary trade-offs at play. While seeds invest heavily in nourishing embryos, spores prioritize longevity and dispersal, often at the expense of immediate growth potential. This divergence is why spore-bearing species dominate in extreme environments, from Antarctic mosses to geothermal hot springs. For conservationists, understanding these adaptations is crucial—spore banks, akin to seed banks, could safeguard biodiversity in the face of climate change, preserving species that might otherwise vanish under rapid environmental shifts.

In practical terms, harnessing spore adaptations offers tangible benefits. Farmers in arid regions could adopt spore-based techniques to stabilize soil in degraded lands, using species like *Bryum argenteum* that form dense mats resistant to erosion. Hobbyists cultivating carnivorous plants like *Drosera* can optimize spore germination by mimicking natural triggers, such as chilling spores at 4°C for 4–6 weeks before sowing. Even in urban settings, spore-rich lichens can be introduced to green roofs, providing both aesthetic appeal and air-purifying capabilities. By studying these survival strategies, we unlock tools to address challenges from agriculture to ecosystem restoration, proving that spores are not just relics of ancient biology but blueprints for future resilience.

Discovering Timmask Spores: Top Locations for Rare Fungal Finds

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are microscopic, unicellular reproductive units produced by plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. Unlike seeds, spores do not contain an embryo or stored food and are typically produced through asexual or sexual reproduction in alternation of generations.

Spores are lightweight, durable, and can remain dormant for long periods, allowing plants to survive unfavorable conditions such as drought, extreme temperatures, or lack of nutrients. Once conditions improve, spores germinate and grow into new plants.

Spore germination begins when a spore lands in a suitable environment with adequate moisture and nutrients. The spore absorbs water, swells, and breaks its protective wall. It then develops into a gametophyte, which can produce gametes for sexual reproduction or grow into a new plant.