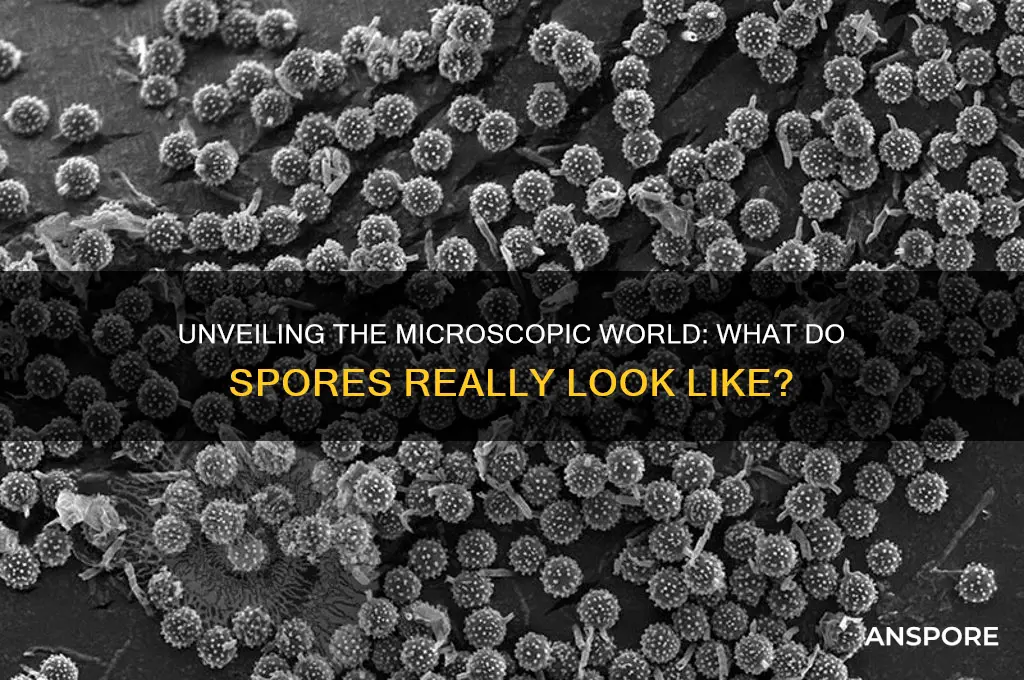

Spores are microscopic, single-celled reproductive structures produced by various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria, designed for survival and dispersal. Typically, they appear as tiny, lightweight particles, often spherical or oval in shape, with sizes ranging from a few micrometers to several tens of micrometers. Their appearance can vary depending on the species; for instance, fungal spores may exhibit smooth or textured surfaces, while plant spores, like those from ferns or mosses, might have distinctive features such as elaters or wings to aid in wind dispersal. Under a microscope, spores often reveal intricate patterns, ridges, or markings that are unique to their species, making them identifiable despite their minuscule size. Their resilient outer walls, composed of materials like chitin or sporopollenin, give them a robust, durable appearance, enabling them to withstand harsh environmental conditions until they germinate under favorable circumstances.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Shape | Spherical, oval, cylindrical, or elongated, depending on the species. |

| Size | Typically 1-100 micrometers (μm) in diameter, though some can be smaller or larger. |

| Color | Often colorless or translucent, but can appear white, yellow, brown, or black when in large quantities. |

| Wall Structure | Composed of a tough, protective outer layer (spore wall) made of sporopollenin, which is highly resistant to environmental stresses. |

| Surface Texture | Smooth, rough, or ornamented with ridges, spines, or other structures, depending on the species. |

| Internal Structure | Contains a nucleus, cytoplasm, and stored nutrients; may have a single or multiple cells. |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals, allowing them to survive harsh conditions. |

| Germination | Remains dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination, leading to the growth of a new organism. |

| Reproduction | Asexual reproductive units produced by fungi, plants (e.g., ferns, mosses), and some bacteria (e.g., endospores). |

| Visibility | Individual spores are microscopic, but large clusters can be visible as powdery or dusty masses. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Shape and Size: Spores vary in shape (round, oval, cylindrical) and size (microns to millimeters)

- Color and Pigmentation: Spores can be colorless, white, yellow, brown, or black due to pigments

- Surface Texture: Smooth, rough, or ornamented surfaces with ridges, spines, or warts

- Wall Structure: Thick or thin walls, single or multilayered, often with distinct layers

- Special Features: Appendages, scars, or specialized structures like elaters or coils

Shape and Size: Spores vary in shape (round, oval, cylindrical) and size (microns to millimeters)

Spores, the microscopic units of life, exhibit a remarkable diversity in shape and size, a feature that is both fascinating and functionally significant. From the perfectly round spores of certain fungi to the elongated, cylindrical forms of others, this variation is not arbitrary. Shape often correlates with the spore's method of dispersal and its environmental niche. For instance, round spores may be optimized for wind dispersal, their symmetry allowing them to travel farther with minimal resistance. In contrast, oval or cylindrical spores might be better suited for attachment to surfaces or for being carried by water, their asymmetry providing a functional advantage in specific conditions.

Size, too, plays a critical role in a spore's survival and propagation. Ranging from a few microns to several millimeters, spore dimensions are finely tuned to their ecological roles. Smaller spores, typically in the micron range, are more easily dispersed by air currents, enabling them to colonize distant environments. Larger spores, on the other hand, often contain more nutrients and are better equipped to survive harsh conditions, such as drought or extreme temperatures. For example, the spores of *Polypore* fungi, which can be up to 100 microns in diameter, are robust and capable of enduring long periods of dormancy until conditions become favorable for growth.

Understanding the shape and size of spores is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications, particularly in fields like agriculture, medicine, and environmental science. For instance, identifying spore morphology can help in diagnosing plant diseases caused by fungal pathogens. Farmers and botanists can use this knowledge to implement targeted control measures, such as applying fungicides that are effective against specific spore types. Similarly, in allergology, recognizing the shape and size of airborne spores can aid in predicting and managing allergic reactions, as certain spore types are more likely to trigger symptoms in sensitive individuals.

To observe spores firsthand, one can use a simple light microscope with a magnification of at least 400x. Collecting samples from plants, soil, or even household surfaces can reveal a hidden world of diversity. For example, placing a piece of tape on a moldy surface and examining it under the microscope will showcase spores in various shapes and sizes, from the round spores of *Aspergillus* to the oval ones of *Penicillium*. This hands-on approach not only deepens appreciation for microbial life but also underscores the importance of spore morphology in their ecological roles.

In conclusion, the shape and size of spores are not merely aesthetic traits but are deeply intertwined with their survival strategies and ecological functions. By studying these characteristics, we gain insights into the adaptive mechanisms of microorganisms and their interactions with the environment. Whether for scientific research, practical applications, or personal curiosity, exploring the diversity of spore morphology opens a window into the intricate world of life at its smallest scale.

Do Fungi Release Spores? Unveiling the Fascinating Fungal Reproduction Process

You may want to see also

Color and Pigmentation: Spores can be colorless, white, yellow, brown, or black due to pigments

Spores, the microscopic reproductive units of fungi, algae, and some plants, exhibit a surprising range of colors due to the presence of pigments. These hues—colorless, white, yellow, brown, or black—are not merely aesthetic but often serve critical ecological functions. For instance, melanin, a pigment responsible for black or dark brown spores, provides protection against UV radiation, enhancing survival in harsh environments. Understanding these color variations can aid in species identification and ecological research, making pigmentation a key feature in spore analysis.

To observe spore color, a simple yet effective method involves preparing a spore print. Place the spore-producing structure, such as a mushroom cap, gills down on a white or black surface (paper or glass) for 24 hours. The resulting spore deposit will reveal its color, which can range from the bright yellow of *Agaricus* species to the deep black of *Coprinus*. This technique is particularly useful for amateur mycologists and educators, offering a hands-on way to study pigmentation without specialized equipment.

The ecological significance of spore color extends beyond identification. Lighter-colored spores, like those of *Puccinia* (rust fungi), are often wind-dispersed and lack heavy pigments to remain airborne. In contrast, darker spores, such as those of *Aspergillus*, may be adapted for soil or water dispersal, where UV protection is crucial. This correlation between color and dispersal mechanism highlights how pigmentation is a functional adaptation rather than a random trait.

For those interested in practical applications, spore color can be a diagnostic tool in agriculture and medicine. For example, black spores of *Alternaria* fungi, a common plant pathogen, can indicate crop infections when identified in soil samples. Similarly, in clinical settings, the brown spores of *Cladosporium* are a telltale sign of indoor mold contamination. Recognizing these pigments can lead to early intervention, reducing economic and health risks.

In conclusion, the color of spores is a fascinating intersection of biology and ecology, offering insights into species survival strategies and practical applications. Whether through simple spore prints or advanced ecological studies, understanding pigmentation enriches our knowledge of these tiny yet vital organisms. By paying attention to these hues, we unlock a deeper appreciation for the role spores play in their environments.

Can Marijuana Spores Trigger Hives? Exploring the Allergic Reaction Link

You may want to see also

Surface Texture: Smooth, rough, or ornamented surfaces with ridges, spines, or warts

Spores, the microscopic survival units of various organisms, exhibit a remarkable diversity in surface textures that serve both functional and taxonomic purposes. These textures range from smooth and unadorned to intricately ornamented with ridges, spines, or warts. Such variations are not merely aesthetic; they play critical roles in spore dispersal, adhesion, and environmental resilience. For instance, smooth-surfaced spores, like those of certain fungi, often facilitate rapid air travel, while rough or ornamented spores, such as those of ferns, may enhance attachment to surfaces or deter predation. Understanding these textures provides insights into spore biology and ecological adaptation.

To examine spore surface textures, a simple yet effective method involves using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), which reveals details at the micrometer scale. For hobbyists or educators, a basic light microscope with a magnification of at least 400x can also provide valuable observations. When preparing samples, ensure spores are clean and dry; a single drop of water can distort their natural texture. For example, *Lycopodium* spores display a distinctly ridged surface, while *Aspergillus* spores appear smoother under magnification. These observations not only aid in identification but also highlight the evolutionary strategies behind spore design.

From a practical standpoint, spore surface texture influences their behavior in different environments. Smooth spores, like those of *Penicillium*, are more prone to airborne dispersal, making them effective colonizers of new habitats. In contrast, ornamented spores, such as those of *Polypodium* ferns, often rely on water or animal vectors for transport due to their increased friction and adhesion. For gardeners or ecologists, recognizing these textures can inform strategies for plant propagation or pest control. For instance, applying a fine mist of water may aid in dispersing smooth spores, while rough spores might require physical disturbance for release.

A comparative analysis of spore textures reveals fascinating adaptations. Ridges and spines, as seen in *Sphagnum* moss spores, increase surface area, potentially enhancing nutrient absorption or water retention. Warts, common in *Equisetum* spores, may serve as anchors for attachment to substrates. These features are not random but reflect the organism’s life cycle and habitat. For example, aquatic spores often have smoother surfaces to reduce drag, while terrestrial spores may be more textured to withstand desiccation. Such comparisons underscore the interplay between form and function in spore design.

In conclusion, spore surface textures—whether smooth, rough, or ornamented—are key identifiers and functional traits. By observing these features, one gains a deeper appreciation for the ingenuity of nature’s microscopic designs. Whether for scientific research, educational purposes, or practical applications, understanding spore textures opens a window into the hidden world of plant and fungal reproduction. Equip yourself with the right tools, observe closely, and let the diversity of spore surfaces inspire curiosity and discovery.

Understanding Saryn's Spores: Mechanics and Spread Explained in Detail

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Wall Structure: Thick or thin walls, single or multilayered, often with distinct layers

Spores, the resilient reproductive units of various organisms, exhibit a striking diversity in wall structure, a critical feature influencing their survival and function. This structure can vary dramatically, from thin, delicate layers to robust, multilayered fortifications. Understanding these variations provides insight into the spore's role and the organism's evolutionary strategies.

The Spectrum of Wall Thickness:

Spore walls range from paper-thin, almost translucent membranes to thick, impenetrable barriers. Thin walls, often found in certain fungal spores, prioritize rapid germination and dispersal. They allow for quick absorption of water and nutrients, facilitating swift colonization of new environments. Conversely, thick walls, characteristic of bacterial endospores, are designed for endurance. These robust structures can withstand extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and desiccation, ensuring the spore's longevity in harsh environments.

Single vs. Multilayered: A Tale of Complexity

The simplicity of a single-layered wall contrasts sharply with the intricate architecture of multilayered structures. Single layers, common in some plant spores, provide a basic protective barrier, often sufficient for short-term survival and dispersal. Multilayered walls, however, are a testament to evolutionary ingenuity. Each layer can serve a distinct purpose, such as protection against UV radiation, prevention of water loss, or defense against predators. For instance, the spores of some ferns have a multilayered wall with an outer layer rich in sporopollenin, a durable polymer, and an inner layer containing nutrients for the developing embryo.

Distinct Layers: Specialized Functions

The beauty of multilayered spore walls lies in their specialization. Each layer can be tailored to perform specific functions, enhancing the spore's overall fitness. In some fungal spores, the outermost layer is adorned with intricate sculptures or spines, aiding in dispersal by wind or water. Beneath this, a layer rich in melanin provides protection against UV radiation, a common challenge for spores exposed to sunlight. The innermost layers often house the genetic material and essential nutrients, ensuring the spore's viability during dormancy.

Practical Implications: From Agriculture to Medicine

Understanding spore wall structure has practical applications. In agriculture, knowledge of wall thickness and composition can guide the development of effective seed coatings to enhance germination rates. For instance, thin-walled spores might benefit from coatings that provide additional protection during seed treatment processes. In medicine, the study of bacterial endospore walls has led to the development of sterilization techniques capable of penetrating these resilient structures, ensuring the safety of medical equipment and supplies.

A Window into Evolutionary Strategies

The diversity in spore wall structure reflects the myriad challenges organisms face in their environments. Thin walls prioritize rapid reproduction and dispersal, while thick, multilayered walls emphasize long-term survival. This variation is a testament to the ingenuity of evolution, crafting solutions tailored to specific ecological niches. By studying these structures, we gain not only practical knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for the complexity and adaptability of life.

Spore Crashing Issue Resolved: A Comprehensive Update and Review

You may want to see also

Special Features: Appendages, scars, or specialized structures like elaters or coils

Spores, the microscopic units of life, often carry distinctive features that aid in their dispersal, protection, or germination. Among these are appendages, scars, and specialized structures like elaters or coils, which serve as nature’s ingenious adaptations. These features are not merely decorative; they are functional tools that enhance a spore’s survival in diverse environments. For instance, elaters in horsetail spores act as hygroscopic springs, propelling the spores further when humidity changes. Such structures highlight the evolutionary precision behind spore design, turning them into miniature marvels of biology.

To identify these special features, examine spores under a microscope at 400x magnification, using a concave slide to prevent rolling. Look for appendages, which are filamentous extensions that aid in attachment or wind dispersal, often seen in fern spores. Scars, such as the trilete mark in some plant spores, indicate the point of spore separation from the parent plant and can be diagnostic for classification. Specialized structures like coils or elaters require careful observation; elaters, for example, are spiral-shaped and respond to moisture changes, while coils may resemble tiny springs. Documenting these features with detailed sketches or microphotography can aid in accurate identification and study.

From a practical standpoint, understanding these structures is crucial for fields like botany, ecology, and agriculture. For instance, knowing the presence of elaters in horsetail spores can help predict their dispersal patterns, aiding in invasive species management. In forensic science, spore scars can be used to trace plant origins in criminal investigations. For hobbyists or educators, creating a spore collection with labeled features can serve as a hands-on learning tool. Use a spore staining kit (e.g., cotton blue or safranin) to enhance visibility and highlight these structures under a microscope.

Comparatively, while all spores share a common purpose—reproduction—their specialized features reveal unique strategies for survival. Fungal spores often have appendages for adhesion, while bryophyte spores may have elaters for wind dispersal. In contrast, some algae spores develop coils to resist desiccation. This diversity underscores the adaptability of spores across kingdoms. By studying these structures, we gain insights into evolutionary pathways and ecological roles, making spore analysis a fascinating intersection of form and function.

In conclusion, the appendages, scars, and specialized structures of spores are not just microscopic curiosities but essential adaptations that define their lifecycle and ecological impact. Whether you’re a researcher, educator, or enthusiast, recognizing these features opens a window into the intricate world of plant and fungal reproduction. Equip yourself with the right tools—a high-magnification microscope, staining kits, and a keen eye—and explore the hidden complexity of spores. Their special features are a testament to nature’s ingenuity, waiting to be discovered and appreciated.

Toxic Mold Spores: Can They Stick to Clothing and Skin?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores are typically microscopic, single-celled structures that vary in shape, size, and color depending on the species. They can be round, oval, cylindrical, or elongated, often with distinctive features like ridges, spines, or appendages.

Yes, spores can range in color from colorless or translucent to yellow, green, brown, or black, depending on the organism producing them and the pigments present in their cell walls.

Most individual spores are too small to see without a microscope, but in large quantities, they may appear as a fine powder or dust, often with a noticeable color, such as the orange spores of rust fungi or the black spores of certain molds.

No, spores vary widely in appearance. For example, bacterial spores are often oval and smooth, fungal spores can have intricate shapes and textures, and plant spores (like those from ferns or mosses) may have unique structures for dispersal.

Yes, the shape, size, color, and surface features of spores are key characteristics used in identifying the species of the organism that produced them, often requiring a microscope for detailed examination.