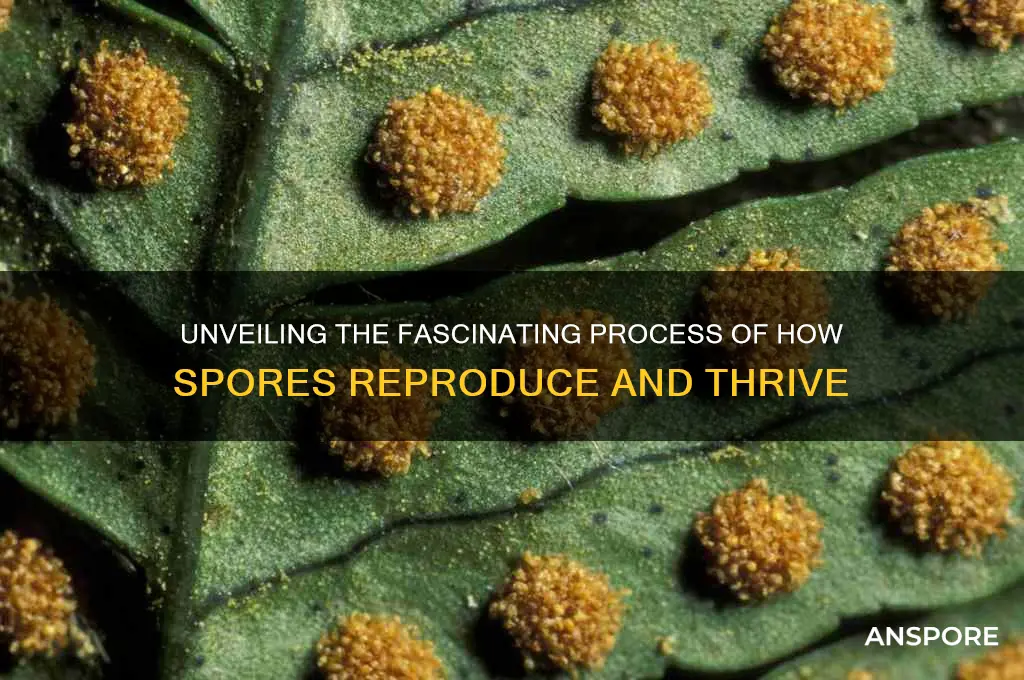

Spores are a remarkable reproductive strategy employed by various organisms, including fungi, plants, and some bacteria, to propagate and survive in diverse environments. Unlike seeds, spores are typically single-celled and lack an embryo, relying instead on their ability to disperse widely and germinate under favorable conditions. Reproduction via spores involves a process called sporulation, where the parent organism produces specialized cells that can remain dormant for extended periods, enduring harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, drought, or lack of nutrients. When conditions improve, these spores germinate, developing into new individuals. This method ensures the survival and dispersal of species across vast distances and challenging habitats, making spores a highly efficient and resilient means of reproduction in the natural world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Asexual (primarily) |

| Process | Sporulation (formation of spores within a sporangium) |

| Sporangium | Specialized structure where spores develop |

| Types of Spores | Endospores (bacterial), Conidia (fungal), Spores (plant) |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to harsh conditions (heat, radiation, desiccation) |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods until favorable conditions arise |

| Dispersal | Dispersed by wind, water, animals, or other environmental factors |

| Germination | Spores germinate when conditions are suitable, forming new organisms |

| Genetic Variation | Limited genetic variation in asexual spores; some fungi produce sexual spores with genetic recombination |

| Examples | Bacteria (e.g., Bacillus), Fungi (e.g., molds, mushrooms), Plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) |

| Ecological Role | Key role in survival, dispersal, and colonization of new habitats |

Explore related products

$9.95 $11.99

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: Formation of spores within sporangia, triggered by environmental stress or nutrient depletion

- Germination Mechanism: Spores activate and grow into new organisms under favorable conditions

- Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new habitats for colonization

- Types of Spores: Classification based on structure, function, and reproductive strategies (e.g., endospores, zygospores)

- Survival Adaptations: Spores withstand extreme conditions like heat, cold, or desiccation for long-term survival

Sporulation Process: Formation of spores within sporangia, triggered by environmental stress or nutrient depletion

Spores are nature's survival capsules, and their formation is a fascinating response to adversity. When faced with environmental stress or nutrient scarcity, certain organisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and some plants, initiate a process called sporulation. This intricate mechanism ensures the continuation of their species even in the harshest conditions.

The Sporulation Journey:

Imagine a microscopic factory springing into action when resources dwindle. This is the sporangium, a specialized structure where spores are produced. The process begins with a signal, often triggered by factors like dehydration, extreme temperatures, or limited food sources. For instance, in bacteria like *Bacillus subtilis*, the lack of nutrients activates a genetic program, prompting the cell to divide asymmetrically, forming a smaller cell that will become the spore. This initial step is crucial, as it sets the stage for the transformation.

A Complex Transformation:

Sporulation is a highly regulated, multi-step process. In fungi, such as the common bread mold *Neurospora crassa*, the sporangium develops from a network of filaments called hyphae. As nutrients deplete, these hyphae aggregate, forming a compact structure. Within this structure, cells differentiate, with some becoming spore mother cells. Each mother cell then undergoes meiosis, producing haploid spores. This reduction in chromosome number is a key strategy for genetic diversity, ensuring the species' adaptability.

Survival Strategies:

The formation of spores is a survival tactic, allowing organisms to endure until conditions improve. Spores are incredibly resilient, capable of withstanding extreme temperatures, radiation, and desiccation. For example, bacterial endospores can survive for years, even decades, in a dormant state. This resilience is attributed to their unique structure, which includes a thick, protective coat and minimal water content. When the environment becomes favorable again, spores germinate, resuming growth and reproduction.

Practical Implications:

Understanding sporulation has practical applications, especially in fields like agriculture and medicine. For farmers, knowing how plant pathogens sporulate can inform strategies to prevent crop diseases. In healthcare, studying bacterial sporulation helps develop sterilization techniques and antibiotics. For instance, autoclaves use high pressure and temperature to kill spores, ensuring medical equipment is sterile. Additionally, researchers are exploring ways to disrupt sporulation in harmful bacteria, offering potential new avenues for infection control.

In essence, the sporulation process is a remarkable adaptation, showcasing the ingenuity of nature's survival strategies. From the initial trigger to the formation of resilient spores, this mechanism ensures the persistence of life, even in the face of adversity. By studying these processes, scientists unlock valuable knowledge with wide-ranging applications, from preserving food to combating diseases.

Do Spores Require Sperm Fertilization for Reproduction and Growth?

You may want to see also

Germination Mechanism: Spores activate and grow into new organisms under favorable conditions

Spores, the resilient survival units of various organisms, remain dormant until conditions are just right for growth. This germination mechanism is a finely tuned process, triggered by specific environmental cues such as moisture, temperature, and nutrient availability. For instance, fungal spores often require a water film to initiate metabolic activity, while some bacterial spores, like those of *Bacillus anthracis*, need specific nutrients and a temperature range of 25–35°C to activate. Understanding these triggers is crucial for both harnessing spores in agriculture and preventing unwanted growth in food preservation.

The activation of spores is a multi-step process that begins with the uptake of water, known as imbibition. This rehydrates the spore’s cellular machinery, breaking its dormancy. In plants like ferns, spores germinate into protonemata, tiny filamentous structures, only when humidity levels exceed 80%. For bacterial spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum*, activation involves the release of dipicolinic acid, a process requiring calcium and specific enzymes. Each organism’s germination pathway is unique, tailored to its ecological niche, ensuring survival in harsh conditions.

Once activated, spores undergo rapid cell division and growth, fueled by stored energy reserves like lipids and proteins. For example, moss spores develop into gametophytes within 2–3 weeks under optimal light and moisture conditions. In contrast, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus*, form germ tubes within hours, quickly colonizing substrates. This phase is critical for establishing a new organism, and its success depends on the spore’s ability to detect and respond to environmental signals, such as pH levels or light exposure.

Practical applications of spore germination are vast. In horticulture, controlling humidity and temperature can optimize fern spore growth, ensuring healthy plantlets. In food safety, understanding bacterial spore activation helps design sterilization processes, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes to destroy *Clostridium* spores. Conversely, in biotechnology, spores of *Bacillus thuringiensis* are activated under controlled conditions to produce bioinsecticides. By manipulating germination mechanisms, we can either promote beneficial growth or prevent harmful outbreaks.

To harness or inhibit spore germination effectively, precision is key. For home gardeners, maintaining a consistent moisture level and using sterile soil can enhance moss or fern spore success. In industrial settings, monitoring water activity (aw) below 0.90 prevents fungal spore activation in stored grains. Even in medicine, spore germination studies inform antifungal drug development, targeting enzymes like germinative kinases. Whether fostering life or preventing it, the germination mechanism of spores offers a powerful tool when understood and applied with care.

Understanding C. Diff Spore Shedding: Transmission, Risks, and Prevention

You may want to see also

Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, or animals carry spores to new habitats for colonization

Spores, the microscopic units of reproduction for many plants, fungi, and some bacteria, rely on dispersal to colonize new habitats. Unlike seeds, which often contain stored nutrients and protective coatings, spores are lightweight and resilient, designed for travel. Their dispersal methods—wind, water, and animals—capitalize on natural forces and behaviors to ensure survival and propagation across diverse environments.

Wind dispersal is one of the most common methods, particularly for fungi and ferns. Spores released into the air can travel vast distances, carried by currents and turbulence. For example, a single puffball mushroom can release trillions of spores in a single discharge, relying on wind to scatter them far and wide. To maximize this strategy, spores are often equipped with structures like wings or lightweight shells, as seen in dandelion seeds. Practical tip: If you’re cultivating spore-producing plants indoors, ensure good air circulation to mimic natural dispersal conditions.

Water dispersal is another effective method, especially for aquatic or semi-aquatic organisms. Spores released into water can be carried downstream, colonizing new areas along riverbanks or in stagnant pools. Algae and certain fungi excel at this, with spores that can remain viable for extended periods in water. For instance, the spores of *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, a fungus affecting amphibians, can survive in water for weeks, spreading to new habitats via streams and ponds. Caution: If managing aquatic ecosystems, monitor water flow to control unintended spore dispersal.

Animal dispersal leverages the movement of creatures to transport spores. This method is less common but highly effective for specific species. Spores may attach to an animal’s fur, feathers, or skin, hitching a ride to new locations. For example, the spores of certain fungi, like those in the genus *Pilobolus*, are ejected with force and can stick to passing insects. Similarly, birds and mammals can inadvertently carry spores on their bodies or in their digestive systems after consuming spore-bearing plants. Takeaway: When designing wildlife-friendly gardens, include spore-producing plants to support natural dispersal processes.

Each dispersal method highlights the adaptability of spores to their environment. Wind and water dispersal rely on passive transport, while animal dispersal often involves more direct interaction. Understanding these mechanisms not only sheds light on the reproductive strategies of spore-producing organisms but also informs conservation and cultivation efforts. By mimicking or managing these natural processes, we can enhance the success of spore-dependent species in both wild and controlled settings.

Can Air Purifiers Effectively Remove Mold Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Types of Spores: Classification based on structure, function, and reproductive strategies (e.g., endospores, zygospores)

Spores are microscopic, resilient structures produced by various organisms, primarily for survival and reproduction. Their classification hinges on structure, function, and reproductive strategies, revealing a diverse array of adaptations. For instance, endospores, formed by certain bacteria like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are dormant, highly resistant cells encased in a protective layer. They withstand extreme conditions—heat, radiation, and chemicals—and germinate when the environment becomes favorable, ensuring species survival. In contrast, zygospores, produced by fungi such as bread molds, result from the fusion of two gametangia, serving as a thick-walled, resting stage that protects genetic material during harsh conditions.

Analyzing these structures reveals distinct reproductive strategies. Endospores are asexual, single-celled entities, while zygospores are sexual, formed through conjugation. The former prioritizes endurance, often found in soil or water, waiting for optimal conditions to reactivate. The latter, however, focuses on genetic recombination, enhancing diversity and adaptability. Another example is conidia, asexual spores produced by fungi like *Aspergillus* and *Penicillium*. These are lightweight, easily dispersed by air, and rapidly colonize new environments, showcasing a strategy favoring quick proliferation over long-term survival.

Practical applications of spore classification are evident in industries like food preservation and medicine. Endospores, due to their resistance, pose challenges in sterilization processes, requiring methods like autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes to ensure destruction. Conversely, understanding zygospore formation aids in controlling fungal pathogens in agriculture. For hobbyists or researchers cultivating fungi, recognizing conidia is crucial for successful spore collection and propagation. For instance, placing a mature fungal colony in a sealed container with a damp paper towel can capture conidia for later use.

Comparatively, sporangiospores, produced within sporangia in fungi like *Phycomyces*, illustrate another reproductive strategy. These spores are released en masse, relying on wind dispersal to colonize new habitats. Their thin walls prioritize rapid growth over durability, contrasting with the robust zygospore. Similarly, cysts, formed by protozoa like *Entamoeba*, share structural resilience with endospores but differ in function, serving as a transmission stage rather than a dormant one. Such distinctions highlight the evolutionary tailoring of spores to specific ecological niches.

In conclusion, classifying spores by structure, function, and reproductive strategies uncovers a spectrum of survival mechanisms. From the indestructible endospores to the genetically diverse zygospores, each type exemplifies a unique solution to environmental challenges. Understanding these differences not only advances scientific knowledge but also informs practical applications, from microbial control to biotechnology. Whether in a lab, field, or kitchen, recognizing spore types empowers effective management and utilization of these microscopic marvels.

Does Infinity's End Sell Mushroom Spores? A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Survival Adaptations: Spores withstand extreme conditions like heat, cold, or desiccation for long-term survival

Spores are nature's ultimate survivalists, engineered to endure conditions that would annihilate most life forms. Unlike vegetative cells, spores enter a state of dormancy, reducing metabolic activity to near zero. This metabolic shutdown allows them to withstand extreme temperatures, from the scorching heat of deserts to the freezing cold of polar regions. For example, bacterial endospores can survive temperatures exceeding 100°C, while fungal spores remain viable in subzero environments. This adaptability is not just a passive resistance but an active transformation, where the spore’s cellular structure becomes highly resilient, often coated with protective layers like keratin or chitin.

Desiccation, the complete loss of water, is another challenge spores effortlessly overcome. In dry environments, spores can lose up to 90% of their water content without dying. This is achieved through the accumulation of protective molecules like trehalose, a sugar that stabilizes cell membranes and proteins during dehydration. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can survive in arid conditions for decades, only to revive when water becomes available. This ability to tolerate desiccation is crucial for their dispersal, as it allows them to travel vast distances on wind or water without degradation.

The longevity of spores is a testament to their survival adaptations. Some spores, like those of the bacterium *Clostridium botulinum*, can remain dormant for centuries, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. This long-term survival is facilitated by their ability to repair DNA damage caused by radiation or chemicals, ensuring genetic integrity over time. In contrast, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus*, can persist in soil for years, contributing to their role in nutrient cycling and ecosystem resilience.

Practical applications of spore survival adaptations are vast. In agriculture, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus thuringiensis* are used as biopesticides, surviving harsh field conditions to control pests. In medicine, understanding spore resistance helps develop sterilization methods, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes, to ensure the destruction of pathogens. For outdoor enthusiasts, knowing that spores can survive in extreme conditions underscores the importance of thorough cleaning to prevent contamination, especially in food storage and preparation.

In conclusion, spores’ ability to withstand heat, cold, and desiccation is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. Their survival adaptations not only ensure their persistence in diverse environments but also provide valuable insights for biotechnology and everyday practices. By studying these microscopic survivors, we unlock strategies for preserving life, combating pathogens, and appreciating the resilience of nature’s smallest warriors.

Does the Sporophyte Produce Spores? Unraveling Plant Life Cycle Secrets

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores reproduce through a process called sporulation, where they germinate under favorable conditions, grow into a new organism, and eventually produce more spores to continue the cycle.

Spores are typically a form of asexual reproduction, as they are produced by a single parent organism without the fusion of gametes. However, some organisms use spores in sexual reproduction cycles.

Spores require moisture, warmth, and nutrients to germinate and begin the reproductive process. They are highly resilient and can remain dormant for long periods until conditions are favorable.

No, not all plants and fungi reproduce using spores. While many ferns, mushrooms, and molds rely on spores, other organisms like flowering plants use seeds, and some fungi reproduce via hyphae or other methods.