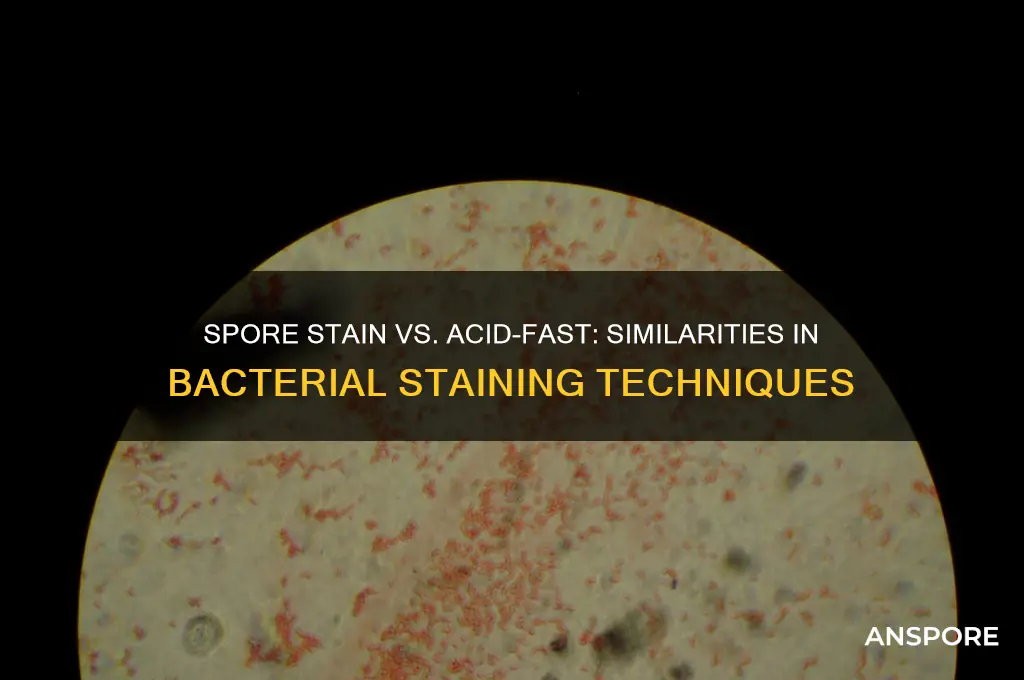

The spore stain and the acid-fast stain are both specialized staining techniques used in microbiology to differentiate specific bacterial structures, yet they share notable similarities in their principles and methodologies. Both stains rely on the differential permeability of bacterial cell walls and the use of heat to drive the primary stain into the cell, followed by a decolorizing step and a counterstain. In the spore stain, heat is applied to force the primary dye (typically malachite green) into the highly resistant spore coat, while in the acid-fast stain, heat is used to drive the primary dye (carbol fuchsin) into the waxy mycolic acid-rich cell walls of acid-fast bacteria. Both techniques employ an acid-alcohol decolorizer to remove the primary stain from non-target structures, leaving the target (spores or acid-fast bacilli) stained and visible against a counterstained background. These parallels highlight the shared reliance on heat, differential staining, and decolorization to identify distinct bacterial features.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heat Fixation | Both spore staining and acid-fast staining require heat fixation of the smear to adhere organisms to the slide, ensuring they withstand the staining process. |

| Primary Stain | Both methods use a primary stain (Malachite green for spores, Carbolfuchsin for acid-fast bacteria) that is applied to the smear. |

| Heat Application | Heat is applied during the primary staining step in both techniques to enhance the penetration of the stain into the organisms. |

| Decolorization | Both stains involve a decolorization step using a solvent (water for spore stain, acid-alcohol for acid-fast stain) to remove the primary stain from non-target organisms. |

| Counterstain | A counterstain (Safranin for both methods) is applied to color the non-spore-forming or non-acid-fast bacteria, providing contrast. |

| Resistance to Decolorization | The target organisms in both stains (spores and acid-fast bacteria) retain the primary stain even after decolorization due to their unique cell wall properties. |

| Final Color | Spores appear green, while acid-fast bacteria appear red, both standing out against the counterstained background. |

| Cell Wall Composition | The resistance to decolorization in both cases is due to the presence of specific cell wall components (spore coat for spores, mycolic acids for acid-fast bacteria). |

| Diagnostic Use | Both stains are used diagnostically to identify specific types of bacteria (spore-forming bacteria and mycobacteria, respectively). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Heat application: Both require heat to drive stain into bacterial cell walls for effective visualization

- Primary stain: Carbol fuchsin is the primary stain used in both staining procedures

- Decolorization step: Both involve a decolorization step using a strong acid-alcohol solution

- Cell wall structure: Target bacteria with waxy cell walls, like Mycobacteria and spores

- Resistance mechanism: Acid-fast and spore-stained cells resist decolorization due to their lipid-rich walls

Heat application: Both require heat to drive stain into bacterial cell walls for effective visualization

Heat is a critical component in both the spore stain and the acid-fast stain, serving as the driving force that pushes the stain into the bacterial cell walls for effective visualization. In the spore stain, heat fixation is applied to kill the bacteria and adhere them to the slide, but its primary role is to facilitate the penetration of the primary stain, typically malachite green, into the spore’s highly resistant outer coat. Similarly, in the acid-fast stain, heat is used during the application of the primary stain, carbol fuchsin, to ensure it permeates the waxy mycolic acid layer of the cell wall in organisms like *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*. Without heat, both stains would fail to bind effectively, rendering the microorganisms invisible under the microscope.

The application of heat in these staining techniques is not arbitrary but follows precise protocols to ensure consistency and reliability. For the spore stain, the slide is typically heated over a flame or on a heated plate for 3–5 minutes while the malachite green is applied. This duration is crucial; insufficient heating may result in incomplete staining, while overheating can damage the sample. In the acid-fast stain, the carbol fuchsin is heated gently (usually by steaming or using a water bath at 60–70°C) for 5–10 minutes. This controlled heat application ensures the stain penetrates the lipid-rich cell walls of acid-fast bacteria, which are otherwise impermeable to most dyes.

From a practical standpoint, the heat step in both stains requires careful attention to avoid common pitfalls. For instance, in the spore stain, uneven heating can lead to inconsistent results, so technicians often use a heating plate with a uniform temperature. In the acid-fast stain, overheating the carbol fuchsin can cause it to precipitate, rendering it ineffective. Additionally, the heat source must be consistent—flame heating is less controlled and riskier than a water bath or steam, which provide even, gentle heat. These nuances highlight why heat application is both an art and a science in microbiological staining.

Comparatively, the role of heat in these stains underscores a shared principle in microbiology: overcoming the natural barriers of bacterial cell walls. While the spore stain targets the resilient spore coat and the acid-fast stain addresses the waxy mycolic acid layer, both rely on heat to bypass these defenses. This similarity is not coincidental but reflects the evolutionary adaptations of these microorganisms, which have developed robust cell wall structures to survive harsh conditions. By leveraging heat, microbiologists can reveal these otherwise hidden structures, enabling accurate identification and diagnosis.

In conclusion, the heat application step in both the spore stain and the acid-fast stain is a cornerstone of their effectiveness, transforming otherwise invisible microbial features into clear, distinguishable structures. Whether in a clinical laboratory diagnosing tuberculosis or identifying spore-forming bacteria in environmental samples, mastering this technique is essential. By understanding the specific requirements and potential challenges of heat application, technicians can ensure reliable results, contributing to accurate microbial identification and, ultimately, better patient outcomes.

Can Spores Survive Stomach Acid? Unraveling the Digestive Mystery

You may want to see also

Primary stain: Carbol fuchsin is the primary stain used in both staining procedures

Carbol fuchsin, a vibrant red dye, serves as the cornerstone of both the spore stain and the acid-fast stain, despite their distinct purposes. This shared primary stain is no coincidence; its unique chemical properties make it ideal for penetrating the robust cell walls of both spores and acid-fast bacteria. In the spore stain, carbol fuchsin's affinity for the impermeable spore coat allows it to impart a deep red color, distinguishing spores from vegetative cells. Similarly, in the acid-fast stain, carbol fuchsin readily enters the waxy mycolic acid-rich cell walls of Mycobacteria, staining them red. This commonality in primary stain choice highlights a fundamental similarity in the staining challenges posed by these two resilient microbial forms.

The application of carbol fuchsin in both staining procedures follows a similar protocol. A 5% aqueous solution of carbol fuchsin is typically used, heated gently to enhance penetration. For spore staining, the heat treatment is crucial, as it helps the dye breach the spore's resistant outer layers. In acid-fast staining, heat is also applied, but the primary barrier to overcome is the waxy cell wall. This shared heating step underscores the need for a dye capable of withstanding elevated temperatures without losing its staining efficacy.

While carbol fuchsin is the primary stain in both procedures, the subsequent steps diverge significantly. In spore staining, a decolorizer like water or alcohol is used to remove the dye from vegetative cells, leaving only the spores stained red. In contrast, acid-fast staining employs a strong acid-alcohol decolorizer to remove carbol fuchsin from non-acid-fast bacteria, while the dye remains firmly bound to the mycolic acid-rich cell walls of Mycobacteria. This difference in decolorization reflects the distinct cellular compositions of spores and acid-fast bacteria, despite their shared reliance on carbol fuchsin as the initial stain.

The use of carbol fuchsin in both staining procedures offers a practical advantage in laboratory settings. Stock solutions of the dye can be prepared and used interchangeably, streamlining workflow and reducing costs. However, it's essential to note that the concentration and application time of carbol fuchsin may vary slightly between the two stains. For spore staining, a shorter staining time (typically 5-10 minutes) is often sufficient, while acid-fast staining may require a longer incubation (up to 15 minutes) to ensure complete penetration of the waxy cell wall. By understanding these nuances, laboratory technicians can optimize their staining protocols and achieve accurate, reliable results.

Can Mold Spores Enter Your Ears? Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Decolorization step: Both involve a decolorization step using a strong acid-alcohol solution

The decolorization step is a critical phase in both the spore stain and the acid-fast stain, serving as a defining moment that separates the resilient from the transient. In this step, a strong acid-alcohol solution is employed to differentiate between cell types based on their resistance to decolorization. For instance, in the spore stain, the solution typically consists of 3% hydrochloric acid in 95% ethanol, applied for 10-15 seconds, targeting the removal of primary dye from vegetative cells while leaving spore-specific stains intact. Similarly, the acid-fast stain uses a 0.5-1% sulfuric acid in 95% ethanol solution for 3-5 minutes, distinguishing acid-fast bacteria like Mycobacterium from non-acid-fast organisms.

To execute this step effectively, precision and timing are paramount. In a laboratory setting, technicians must ensure the acid-alcohol solution is mixed in the correct proportions, as deviations can lead to incomplete decolorization or damage to the sample. For the spore stain, a brief exposure is sufficient, whereas the acid-fast stain requires a longer duration due to the robustness of the cell walls in acid-fast bacteria. It’s crucial to monitor the process under a microscope or timer to avoid over-decolorization, which could result in false-negative results. Practical tips include pre-warming the solution to room temperature and using a dropper for controlled application, ensuring uniformity across the slide.

Comparatively, the decolorization step highlights a shared principle in both staining techniques: the exploitation of cellular structural differences. While spores and acid-fast bacteria share a resistance to decolorization due to their waxy cell walls, the specific mechanisms differ. Spores owe their resilience to the presence of dipicolinic acid and calcium ions, whereas acid-fast bacteria rely on mycolic acids in their cell walls. This distinction underscores the importance of tailoring the decolorization solution’s strength and duration to the target organism, ensuring accurate differentiation without compromising sample integrity.

From a practical standpoint, mastering the decolorization step requires attention to detail and adherence to protocol. For educators and students, demonstrating this step with side-by-side comparisons of spore and acid-fast stains can illuminate the similarities and differences in their mechanisms. For clinical laboratories, consistent results depend on standardized procedures, including the use of calibrated timers and pre-measured solutions. A common pitfall to avoid is reusing decolorizing agents, as their potency diminishes with each use, leading to inconsistent outcomes. By treating this step as a precise, controlled process, technicians can ensure reliable and reproducible results in both staining techniques.

Mould Spores and Health: Uncovering Hidden Risks in Your Home

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$8.37 $11.59

Cell wall structure: Target bacteria with waxy cell walls, like Mycobacteria and spores

The unique cell wall composition of certain bacteria, particularly those with waxy cell walls like Mycobacteria and spores, plays a pivotal role in their staining characteristics. These organisms possess a complex cell wall structure that includes a high lipid content, primarily mycolic acids in Mycobacteria and dipicolinic acid in spores. This waxy layer acts as a barrier, making these bacteria resistant to many common staining techniques. However, both the spore stain and the acid-fast stain are specifically designed to penetrate this lipid-rich barrier, allowing for the differentiation of these bacteria from others.

To effectively target bacteria with waxy cell walls, the staining process must overcome the hydrophobic nature of these lipids. The acid-fast stain, for example, uses a combination of carbol fuchsin and heat to force the dye through the cell wall. Similarly, the spore stain employs heat and a primary stain like malachite green to achieve the same goal. Both methods rely on the principle of lipid solubility, where the dye molecules dissolve in the waxy layer, ensuring that the stain is retained even after decolorization. This shared mechanism highlights a fundamental resemblance between the two staining techniques.

When performing these stains, it’s crucial to follow precise steps to ensure accuracy. For the acid-fast stain, heat the carbol fuchsin solution until steam rises, and maintain this temperature for 5–10 minutes to drive the dye into the cell wall. After rinsing, decolorize with acid alcohol for 1–3 minutes, followed by counterstaining with methylene blue. For the spore stain, heat the malachite green solution for 5 minutes, allow it to cool, and then apply it to the smear for 5–10 minutes. Decolorize with water, ensuring all vegetative cells are washed away, leaving only the green-stained spores. These steps underscore the importance of heat and lipid-soluble dyes in targeting waxy cell walls.

A comparative analysis reveals that while both stains target waxy cell walls, they serve different diagnostic purposes. The acid-fast stain is primarily used to identify Mycobacteria, such as *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, which are clinically significant pathogens. In contrast, the spore stain is used to detect endospores, particularly in species like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, which are important in environmental and food safety contexts. Despite their distinct applications, the underlying principle of lipid penetration remains consistent, demonstrating a clear resemblance in their approach to staining bacteria with waxy cell walls.

In practical terms, understanding the cell wall structure of these bacteria is essential for effective staining and accurate identification. For instance, in a clinical setting, a positive acid-fast stain can prompt further testing for tuberculosis, while a positive spore stain may indicate contamination in a food sample. By recognizing the shared and unique aspects of these staining techniques, microbiologists can tailor their approach to target specific bacteria with waxy cell walls, ensuring reliable results in both diagnostic and research applications.

Are Anthrax Spores Identical? Unraveling the Genetic Similarities and Differences

You may want to see also

Resistance mechanism: Acid-fast and spore-stained cells resist decolorization due to their lipid-rich walls

The resistance of acid-fast and spore-stained cells to decolorization is a fascinating phenomenon rooted in their unique cellular architecture. Both types of cells possess walls enriched with lipids, particularly mycolic acids in acid-fast bacteria and dipicolinic acid in spores. These lipids create a hydrophobic barrier that repels aqueous decolorizing agents, such as acid-alcohol in the acid-fast stain or water in the spore stain. This structural feature ensures the primary stain (carbol fuchsin for acid-fast bacteria, malachite green for spores) remains trapped within the cell, even after rigorous decolorization attempts. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for interpreting staining results and appreciating the resilience of these microorganisms.

To visualize this resistance, consider the staining protocols. In the acid-fast stain, heat is applied to drive carbol fuchsin into the lipid-rich cell wall of mycobacteria. Subsequent exposure to acid-alcohol fails to remove the stain from these cells, while non-acid-fast bacteria are easily decolorized. Similarly, in the spore stain, prolonged heating with malachite green allows the dye to penetrate the spore’s lipid-laden coat. Despite repeated washing with water, the stain persists, highlighting the spore’s impermeability. Both processes underscore the role of lipids in creating a stain-retaining fortress, a trait exploited in diagnostic microbiology to differentiate these organisms from others.

From a practical standpoint, this resistance mechanism has significant implications for laboratory techniques. For instance, when performing an acid-fast stain, ensure the carbol fuchsin is heated to 60°C for 5 minutes to enhance penetration into the mycolic acid layer. Similarly, in spore staining, maintain the malachite green solution at 80°C for 1-2 hours to effectively penetrate the spore coat. These steps are non-negotiable, as inadequate heat application will result in false negatives. Additionally, avoid over-decolorizing, as prolonged exposure to acid-alcohol or water can damage cell structures without removing the stain from acid-fast or spore-forming cells.

A comparative analysis reveals the evolutionary advantage of lipid-rich walls in these organisms. Acid-fast bacteria, such as *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, use mycolic acids to evade host immune responses and resist desiccation. Spores, produced by bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis*, rely on their lipid-rich coats to survive extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and chemicals. This shared adaptation not only ensures their survival but also complicates their eradication, making them clinically significant pathogens. By studying their staining resistance, microbiologists gain insights into their biology and develop targeted strategies for detection and control.

In conclusion, the resistance of acid-fast and spore-stained cells to decolorization is a direct consequence of their lipid-rich walls. This mechanism not only explains their staining behavior but also highlights their evolutionary ingenuity. For laboratory professionals, mastering these staining techniques requires precision in heat application and decolorization steps. By understanding the science behind this resistance, one can accurately identify these microorganisms and appreciate their remarkable adaptability in diverse environments.

Do Archaea Form Spores? Unraveling Their Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both the spore stain and the acid-fast stain are differential staining techniques used to identify specific bacterial structures. The spore stain highlights bacterial endospores, while the acid-fast stain identifies bacteria with waxy cell walls, such as Mycobacteria.

Both techniques involve a primary stain (malachite green for spores, carbol fuchsin for acid-fast bacteria) followed by a decolorizer (water for spores, acid-alcohol for acid-fast bacteria). However, spores retain the primary stain due to their resistant coat, while acid-fast bacteria retain the stain due to their waxy lipid content.

No, the decolorizing agents differ. The spore stain uses water as a decolorizer, which removes the primary stain from vegetative cells but not from spores. In contrast, the acid-fast stain uses acid-alcohol, which decolorizes non-acid-fast bacteria but leaves acid-fast bacteria stained due to their lipid-rich cell walls.