Distinguishing between vegetative cells and spore mother cells is crucial in understanding the life cycles and reproductive strategies of various organisms, particularly in fungi and bacteria. Vegetative cells are primarily responsible for growth, metabolism, and asexual reproduction, maintaining the organism's day-to-day functions. In contrast, spore mother cells are specialized cells that undergo differentiation to produce spores, which serve as survival structures in adverse conditions. Key differences include their roles, morphology, and genetic activity: vegetative cells are typically larger and actively dividing, while spore mother cells are often smaller, metabolically quiescent, and undergo meiosis or other specialized processes to form spores. Additionally, spore mother cells exhibit distinct genetic markers and regulatory mechanisms that distinguish them from their vegetative counterparts, making molecular and microscopic analysis essential for accurate identification.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Cell Type | Vegetative cells are the actively growing and dividing cells of a bacterium, while spore mother cells are specialized cells that form spores under unfavorable conditions. |

| Function | Vegetative cells are responsible for growth, metabolism, and reproduction. Spore mother cells are formed as a survival mechanism to withstand harsh environments. |

| Morphology | Vegetative cells are typically rod-shaped or coccoid, depending on the bacterial species. Spore mother cells are larger and more elongated, often with a distinct shape before spore formation. |

| DNA Content | Vegetative cells contain a single copy of the bacterial chromosome. Spore mother cells undergo DNA replication, resulting in multiple copies of the chromosome before spore formation. |

| Metabolic Activity | Vegetative cells are metabolically active, performing all necessary life functions. Spore mother cells reduce metabolic activity as they prepare to form spores. |

| Cell Wall Composition | Vegetative cells have a typical bacterial cell wall composed of peptidoglycan. Spore mother cells and subsequent spores have a modified, thicker cell wall with additional layers (e.g., cortex, coat) for protection. |

| Division | Vegetative cells divide by binary fission. Spore mother cells undergo asymmetric division to form a spore and a smaller cell (forespore). |

| Environmental Response | Vegetative cells are sensitive to environmental stresses and die under harsh conditions. Spore mother cells initiate spore formation in response to nutrient depletion, desiccation, or other stresses. |

| Longevity | Vegetative cells have a limited lifespan and require favorable conditions to survive. Spores formed from spore mother cells can remain dormant for years or even centuries, surviving extreme conditions. |

| Germination | Vegetative cells do not germinate. Spores can germinate under favorable conditions, reverting to vegetative cells and resuming growth. |

| Genetic Stability | Vegetative cells are prone to mutations during replication. Spores maintain genetic stability due to their dormant state and protective structures. |

| Occurrence | Vegetative cells are present during the active growth phase of bacteria. Spore mother cells are transient and only appear under specific stress conditions. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cell Size and Shape: Vegetative cells are smaller, irregular; spore mother cells are larger, spherical or oval

- Nuclear Characteristics: Vegetative cells have single nuclei; spore mother cells contain multiple, thickened nuclei

- Cell Wall Composition: Vegetative cells have thin walls; spore mother cells develop thicker, resistant walls

- Metabolic Activity: Vegetative cells are metabolically active; spore mother cells reduce activity before sporulation

- Cytoplasmic Changes: Vegetative cells have uniform cytoplasm; spore mother cells show granular, condensed cytoplasm

Cell Size and Shape: Vegetative cells are smaller, irregular; spore mother cells are larger, spherical or oval

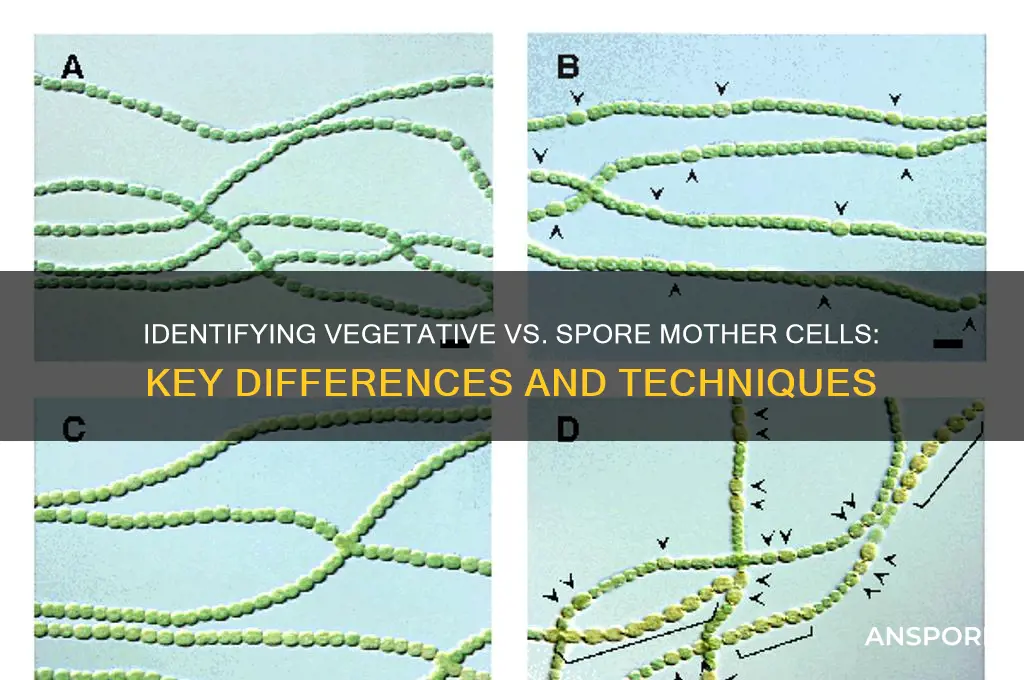

One of the most immediate and observable differences between vegetative cells and spore mother cells lies in their physical dimensions and contours. Vegetative cells, the workhorses of microbial growth and metabolism, typically exhibit smaller sizes and irregular shapes. This irregularity often reflects their dynamic role in adapting to environmental conditions, such as nutrient availability or physical constraints. In contrast, spore mother cells are notably larger and tend to adopt more uniform, spherical, or oval shapes. This distinction is not merely aesthetic; it underscores fundamental differences in their biological functions and developmental stages.

To illustrate, consider *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-studied bacterium that exemplifies this dichotomy. Vegetative cells in this species measure approximately 2–4 micrometers in length and 0.5–1 micrometer in width, with a rod-like shape that can vary depending on growth phase. When environmental conditions deteriorate, some vegetative cells differentiate into spore mother cells, which can reach up to 6–8 micrometers in length and 2–3 micrometers in width. This increase in size is accompanied by a shift toward a more rounded morphology, a critical step in the sporulation process. Observing these changes under a microscope at 1000x magnification can provide a clear visual distinction between the two cell types.

From a practical standpoint, distinguishing between these cells based on size and shape is a valuable skill in microbiology labs. For instance, researchers studying sporulation in *B. subtilis* often use phase-contrast microscopy to monitor the transition from vegetative cells to spore mother cells. A tip for beginners: start by focusing on the overall cell population, then identify the larger, more rounded cells as potential spore mother cells. Confirming this visually can be supplemented with staining techniques, such as DPA (dipicolinic acid) staining, which specifically targets spores but also highlights the developmental stages leading to them.

While size and shape are reliable indicators, it’s important to approach this distinction with caution. Environmental factors, such as nutrient deprivation or osmotic stress, can influence cell morphology, potentially causing vegetative cells to appear larger or more rounded than usual. Conversely, mutations or genetic modifications might alter the typical size and shape of spore mother cells. Therefore, combining morphological observations with additional criteria, such as genetic markers or metabolic activity, ensures accurate identification.

In conclusion, the size and shape of cells serve as a straightforward yet powerful tool for distinguishing between vegetative cells and spore mother cells. By understanding and applying this knowledge, researchers and students alike can gain deeper insights into microbial life cycles and developmental processes. Whether in a classroom or a research setting, mastering this distinction opens doors to more nuanced studies in microbiology.

Can Mold Spores Make You Sick? Understanding Health Risks

You may want to see also

Nuclear Characteristics: Vegetative cells have single nuclei; spore mother cells contain multiple, thickened nuclei

One of the most straightforward ways to distinguish between vegetative cells and spore mother cells lies in their nuclear characteristics. Vegetative cells, the primary form of growth and metabolism in many organisms, typically contain a single nucleus. This nucleus is the command center for cellular activities, directing processes like protein synthesis and DNA replication. In contrast, spore mother cells, which are specialized for reproduction and survival under harsh conditions, exhibit a distinct nuclear feature: they contain multiple, thickened nuclei. This difference is not merely a quirk of biology but a critical adaptation that underscores the unique roles these cells play in the life cycle of organisms.

Analyzing these nuclear characteristics reveals deeper insights into cellular function. The single nucleus in vegetative cells is optimized for efficiency in routine cellular processes. It ensures that resources are allocated primarily to growth and maintenance, which are essential for the organism’s immediate survival. On the other hand, the multiple, thickened nuclei in spore mother cells serve a different purpose. These nuclei are preparing for the division and differentiation required to produce spores, which are resilient structures capable of withstanding extreme environments. The thickening of the nuclei may enhance their durability or facilitate the rapid replication needed for spore formation.

To observe these differences in a practical setting, consider using microscopy techniques such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or DAPI staining. FISH can highlight specific DNA sequences, making it easier to count and compare nuclei in both cell types. DAPI staining, which binds to DNA, will reveal the single nucleus in vegetative cells and the multiple, denser nuclei in spore mother cells. For best results, ensure your samples are fixed properly—use 4% paraformaldehyde for 10–15 minutes at room temperature to preserve nuclear structure without causing damage.

A comparative analysis of these nuclear characteristics also sheds light on evolutionary strategies. Vegetative cells prioritize simplicity and efficiency, reflecting their role in sustaining the organism under normal conditions. Spore mother cells, however, invest in complexity, with multiple nuclei that enable rapid and specialized reproduction. This distinction is particularly evident in fungi and certain bacteria, where spore formation is a survival mechanism. For instance, in *Bacillus subtilis*, the transition from vegetative growth to spore formation involves a dramatic change in nuclear structure, with the spore mother cell developing multiple nuclei to support sporulation.

In conclusion, the nuclear characteristics of vegetative and spore mother cells provide a clear and practical means of differentiation. By focusing on the number and appearance of nuclei, researchers and students alike can gain valuable insights into the functional and evolutionary differences between these cell types. Whether through advanced microscopy techniques or simple staining methods, observing these nuclear features offers a direct window into the specialized roles these cells play in the life cycle of organisms.

Renaming Planets in Spore: Possibilities, Limitations, and Creative Freedom

You may want to see also

Cell Wall Composition: Vegetative cells have thin walls; spore mother cells develop thicker, resistant walls

The cell wall, a defining feature of plant and fungal cells, serves as a protective barrier and structural support. However, not all cell walls are created equal. Vegetative cells, responsible for the day-to-day growth and metabolism of an organism, possess thin, flexible walls. These walls, typically composed of cellulose in plants and chitin in fungi, allow for easy expansion as the cell grows. Imagine a young sapling stretching towards the sun – its vegetative cells are actively dividing and elongating, their thin walls accommodating this rapid growth.

In contrast, spore mother cells, the precursors to resilient spores, undergo a dramatic transformation. As they prepare to produce spores capable of surviving harsh conditions, their cell walls thicken significantly. This thickening involves the deposition of additional layers of material, often including sporopollenin, a highly durable polymer. Think of it as a suit of armor, shielding the developing spore from desiccation, extreme temperatures, and other environmental stresses.

This difference in cell wall composition is a crucial adaptation. The thin walls of vegetative cells prioritize growth and nutrient exchange, while the thick, resistant walls of spore mother cells ensure the survival of the next generation during periods of adversity.

This distinction is not merely academic. Understanding these differences has practical applications. For example, in agriculture, knowing the cell wall composition of different plant tissues can inform strategies for pest control and disease management. Targeting the thinner walls of vegetative cells might be more effective for certain herbicides, while fungicides might need to penetrate the thicker walls of spore-producing structures.

Furthermore, studying cell wall composition can shed light on evolutionary adaptations. The development of thick, resistant walls in spore mother cells likely emerged as a response to the need for long-term survival in unpredictable environments. By comparing cell wall structures across different species, scientists can trace the evolutionary history of spore production and dispersal strategies.

Can Low Humidity Kill Mold Spores? Uncovering the Truth

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Metabolic Activity: Vegetative cells are metabolically active; spore mother cells reduce activity before sporulation

Vegetative cells are the workhorses of bacterial growth, constantly engaged in metabolic processes like nutrient uptake, energy production, and biosynthesis. This high level of activity fuels their rapid division and colony expansion. Imagine a bustling factory: raw materials are constantly being processed, energy is being generated, and new products are being assembled. This is the vegetative cell in its element.

In contrast, spore mother cells, precursors to the highly resistant bacterial spores, undergo a metabolic shift. As they prepare for sporulation, they downregulate many of these energy-intensive processes. This isn't a sudden shutdown, but a strategic slowdown. Think of it as the factory switching from mass production to a specialized, energy-efficient mode, conserving resources for the demanding task of spore formation.

This metabolic slowdown is a crucial step in spore development. By reducing activity, the cell redirects its energy towards synthesizing the specialized structures and protective layers that characterize spores. This includes the thick spore coat, which acts as a barrier against harsh environmental conditions, and the accumulation of dipicolinic acid, a molecule that contributes to spore dormancy and resistance.

This metabolic shift is not merely a passive response to environmental cues. It's a highly regulated process involving complex gene expression changes. Specific genes responsible for vegetative growth are repressed, while those involved in sporulation are activated. This intricate dance of gene regulation ensures that the cell allocates its resources efficiently, prioritizing spore formation over continued growth.

Understanding this metabolic difference is key to distinguishing between vegetative and spore mother cells. Techniques like measuring oxygen consumption rates or analyzing gene expression profiles can provide valuable insights. For instance, a significant decrease in oxygen consumption could indicate a cell transitioning from the vegetative to the spore mother cell state.

Mastering Mushroom Cultivation: A Step-by-Step Guide to Growing Spores

You may want to see also

Cytoplasmic Changes: Vegetative cells have uniform cytoplasm; spore mother cells show granular, condensed cytoplasm

The cytoplasm, a gel-like substance within cells, undergoes distinct transformations when comparing vegetative cells to spore mother cells. A simple yet powerful observation reveals a key difference: uniformity versus granularity. Vegetative cells, the workhorses of an organism's growth and metabolism, exhibit a consistent, homogenous cytoplasm. This uniformity reflects their role in maintaining cellular functions and supporting the organism's daily activities. In contrast, spore mother cells, specialized for reproduction and survival, display a strikingly different cytoplasmic texture.

A Microscopic Journey: Imagine peering through a high-powered microscope, magnifying the cellular world. In a vegetative cell, you'd observe a smooth, even distribution of cytoplasm, akin to a calm, glassy lake. This uniformity is essential for efficient nutrient distribution and waste removal, facilitating the cell's active lifestyle. Now, shift your focus to a spore mother cell. Here, the cytoplasm appears denser, with visible granules and a more condensed structure, resembling a turbulent sea with swirling eddies. This transformation is not merely aesthetic; it signifies a fundamental shift in cellular priorities.

The Science Behind the Granules: The granular appearance in spore mother cells is not random but a strategic adaptation. As these cells prepare for sporulation, they accumulate storage materials like lipids and proteins, which appear as granules under the microscope. This condensation is a survival mechanism, ensuring the spore has the necessary resources to endure harsh conditions. For instance, in bacteria, the cytoplasm of a spore mother cell may contain polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), a type of energy storage polymer, which contributes to the granular texture. This process is highly regulated, with specific genes and enzymes controlling the synthesis and accumulation of these storage compounds.

Practical Implications: Understanding these cytoplasmic changes has practical applications in various fields. In microbiology, distinguishing between vegetative and spore mother cells is crucial for identifying and studying different bacterial life stages. For example, in the food industry, detecting spore mother cells in food products is essential for quality control, as spores can survive extreme conditions and cause spoilage or foodborne illnesses. By recognizing the granular cytoplasm, scientists and technicians can employ targeted strategies to prevent spore formation and ensure product safety.

A Comparative Perspective: The contrast in cytoplasmic appearance between these cell types highlights the remarkable adaptability of cells. While vegetative cells prioritize efficiency and uniformity for daily functions, spore mother cells undergo a dramatic transformation, sacrificing immediate efficiency for long-term survival. This comparison underscores the intricate balance between cellular maintenance and reproductive strategies, offering a fascinating insight into the diversity of cellular life. By studying these cytoplasmic changes, researchers can unlock secrets of cellular differentiation and adaptation, contributing to advancements in fields ranging from microbiology to biotechnology.

Exploring Sexual Reproduction in Fungal Spores: A Comprehensive Overview

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Vegetative cells are typically smaller, uniform in size, and actively involved in growth and metabolism. Spore mother cells, in contrast, are larger, often swollen, and specifically dedicated to the formation of spores, showing distinct changes in shape and size during sporulation.

Staining with dyes like DAPI or Hoechst can highlight DNA content; spore mother cells often exhibit condensed or more intense nuclear staining due to their specialized role in spore formation. Additionally, phase-contrast microscopy can reveal the thicker cell walls and altered morphology of spore mother cells.

Yes, spore mother cells express specific genes and proteins associated with sporulation, such as sigma factors (e.g., σ^H^ in *Bacillus subtilis*). PCR or immunostaining for these markers can help distinguish between the two cell types. Vegetative cells, on the other hand, express genes related to general metabolism and growth.