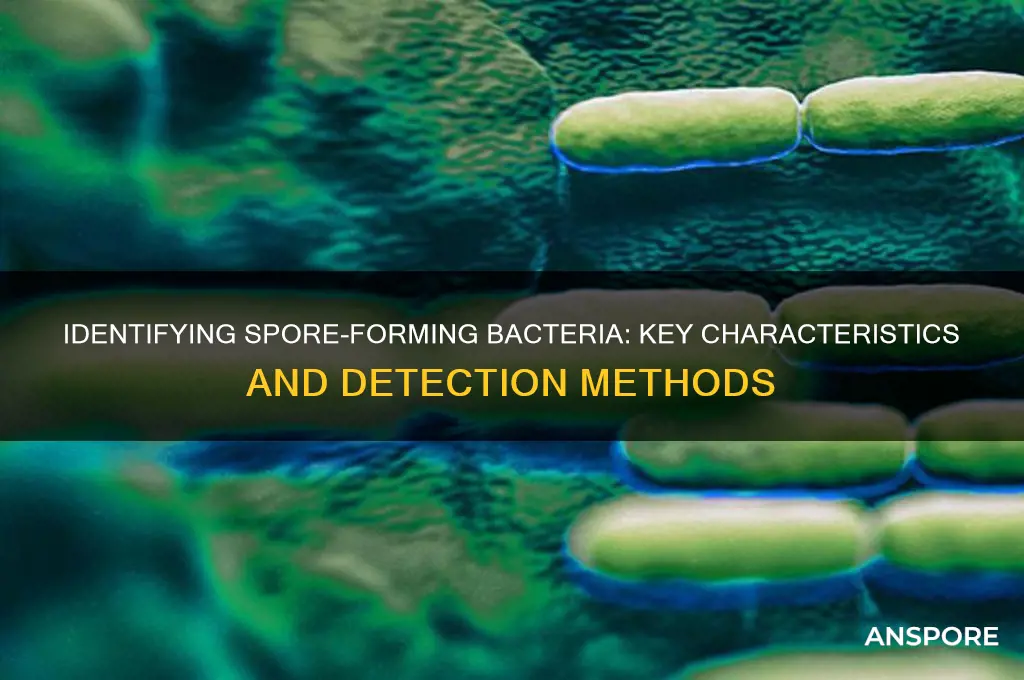

Determining whether a bacterium is spore-forming is crucial in microbiology, as spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to survive harsh conditions. Spore-forming bacteria, such as those in the genus *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, produce endospores through a process called sporulation. To identify if a bacterium is spore-forming, several methods can be employed. Microscopic examination using specialized staining techniques, like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain, can reveal the presence of endospores, which appear as refractile bodies within the bacterial cell. Additionally, culturing the bacteria under stress conditions, such as heat or desiccation, and observing their survival can indicate spore formation. Molecular techniques, including PCR targeting sporulation-specific genes, also provide a definitive identification. Understanding whether a bacterium is spore-forming is essential for applications in food safety, medicine, and environmental studies, as spores pose unique challenges in disinfection and preservation.

What You'll Learn

- Look for endospores: Use staining techniques like Schaeffer-Fulton to visualize endospores under a microscope

- Heat resistance test: Expose bacteria to high temperatures; spore-formers survive, while others die

- Check genus/species: Common spore-forming bacteria include Bacillus, Clostridium, and Sporosarcina

- Observe colony morphology: Spore-formers may show irregular or wrinkled colony edges on agar plates

- Test for dormancy: Spores remain dormant in harsh conditions, reactivating when conditions improve

Look for endospores: Use staining techniques like Schaeffer-Fulton to visualize endospores under a microscope

Endospores are a hallmark of spore-forming bacteria, serving as highly resistant structures that enable survival in harsh conditions. To determine if a bacterium is spore-forming, one of the most reliable methods is to look for these endospores using staining techniques. The Schaeffer-Fulton stain is a widely used and effective method for visualizing endospores under a microscope. This technique leverages the unique properties of endospores, which are more resistant to staining than the vegetative cell, allowing them to appear as distinct, refractile bodies within the bacterial cell.

The Schaeffer-Fulton staining procedure involves several steps, each critical for successful visualization. Begin by preparing a heat-fixed smear of the bacterial sample on a microscope slide. Heat fixation not only adheres the bacteria to the slide but also helps in maintaining the structural integrity of the endospores. Next, flood the slide with malachite green, the primary stain, and heat the slide gently. This process, known as steaming, allows the malachite green to penetrate the spore’s outer layers, staining it green. After rinsing, counterstain the slide with safranin to color the vegetative cell pink or red, providing a clear contrast between the spore and the rest of the cell.

One of the key advantages of the Schaeffer-Fulton stain is its specificity. Endospores appear as bright green, oval or round structures within the pink or red vegetative cell, making them easily identifiable under a light microscope at 1000x magnification. This clear differentiation is crucial for accurate identification, especially in mixed cultures or environmental samples where non-spore-forming bacteria may be present. For best results, ensure the slide is not overheated during steaming, as excessive heat can degrade the sample or cause the malachite green to precipitate, obscuring the endospores.

While the Schaeffer-Fulton stain is highly effective, it’s important to note its limitations. Not all endospores stain equally well, and some species may require modifications to the technique. For example, older endospores or those in dormant states may be more resistant to staining. Additionally, the technique is best suited for Gram-positive bacteria, as Gram-negative bacteria with endospores are rare and may require alternative methods. Always compare stained samples with known positive and negative controls to ensure accuracy.

In practical applications, the Schaeffer-Fulton stain is invaluable in clinical, environmental, and industrial microbiology. It aids in identifying spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridium* and *Bacillus* species, which are relevant in food spoilage, fermentation, and disease diagnosis. For students and researchers, mastering this technique provides a foundational skill in bacterial morphology and physiology. With its simplicity, reliability, and specificity, the Schaeffer-Fulton stain remains a cornerstone in determining whether a bacterium is spore-forming, offering clear visual evidence under the microscope.

Play Spore Without a Registration Code: Easy Steps Guide

You may want to see also

Heat resistance test: Expose bacteria to high temperatures; spore-formers survive, while others die

Spore-forming bacteria possess a remarkable survival mechanism: the ability to withstand extreme conditions by forming highly resistant spores. This adaptability makes them a significant concern in various industries, from food safety to healthcare. One of the most definitive ways to identify these resilient organisms is through a heat resistance test, a straightforward yet powerful method that leverages their unique ability to endure high temperatures.

The Test in Action: Imagine a laboratory setting where a bacterial sample is subjected to a temperature of 80°C (176°F) for 10 minutes. This is a common protocol used in heat resistance tests. Non-spore-forming bacteria, such as *Escherichia coli* or *Staphylococcus aureus*, would typically be eradicated under these conditions due to the denaturation of their proteins and disruption of cellular structures. In contrast, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus cereus* or *Clostridium botulinum* can survive, and in some cases, even thrive, thanks to their protective spore coats. These spores are designed to endure harsh environments, including heat, desiccation, and radiation, ensuring the bacteria's long-term survival.

Practical Application: In the food industry, this test is crucial for ensuring product safety. For instance, canned foods are often heated to temperatures above 100°C (212°F) to kill any potential pathogens. However, spore-formers can survive such processes, leading to food spoilage or even botulism if the spores germinate and grow. By conducting heat resistance tests, manufacturers can identify the presence of spore-forming bacteria and implement additional measures, such as adjusting processing times or temperatures, to guarantee product safety.

A Comparative Perspective: The heat resistance test is particularly valuable when compared to other identification methods. While microscopic examination can reveal spore structures, it may not always be conclusive, especially for inexperienced observers. Molecular techniques like PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) are highly sensitive but can be costly and time-consuming. In contrast, the heat resistance test offers a rapid, cost-effective, and reliable alternative. It provides a clear-cut result: survival indicates spore formation, while death suggests otherwise.

Optimizing the Test: To ensure accuracy, it's essential to control variables such as temperature, duration, and bacterial concentration. For instance, using a water bath or oil bath can provide a uniform heat source, and digital thermometers can monitor temperature precisely. Additionally, standardizing the bacterial suspension's concentration ensures consistency across tests. This method's simplicity and specificity make it an invaluable tool for microbiologists, food scientists, and quality control professionals, offering a quick assessment of bacterial resistance and guiding appropriate treatment or processing strategies.

Are Spores a Fungus? Unraveling the Microscopic Mystery

You may want to see also

Check genus/species: Common spore-forming bacteria include Bacillus, Clostridium, and Sporosarcina

One of the most straightforward ways to determine if a bacterium is spore-forming is to check its genus and species. Certain bacterial genera are well-known for their ability to produce spores as a survival mechanism. Among these, Bacillus, Clostridium, and Sporosarcina stand out as the most common spore-forming bacteria. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, and *Clostridium botulinum*, responsible for botulism, are notorious for their spore-forming capabilities. Identifying the genus and species through methods like 16S rRNA sequencing or biochemical tests can quickly narrow down whether the bacterium in question is likely to form spores.

From an analytical perspective, the presence of these genera in a sample should immediately raise suspicion of spore formation. However, it’s crucial to note that not all species within these genera are spore-formers. For example, while *Bacillus subtilis* is a well-documented spore-former, *Bacillus cereus* can also form spores but is more commonly associated with foodborne illness. Similarly, *Clostridium difficile*, a major cause of hospital-acquired infections, forms highly resistant spores. Cross-referencing the specific species with databases like the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) can provide clarity on its spore-forming potential.

If you’re working in a laboratory setting, a practical tip is to use selective media or staining techniques to confirm spore presence. For instance, a spore stain (e.g., the Schaeffer-Fulton stain) will differentiate spores from vegetative cells, as spores retain the primary stain (green) while vegetative cells appear red. Additionally, culturing the bacterium on nutrient agar and observing colony morphology can provide clues; spore-forming bacteria often produce rough, irregular colonies. Pairing these observations with genus/species identification ensures a more accurate determination.

A comparative approach reveals that while spore-forming bacteria share the ability to produce spores, the triggers and conditions for sporulation vary. For example, *Bacillus* species typically sporulate in response to nutrient depletion, while *Clostridium* species often require anaerobic conditions. *Sporosarcina*, less commonly encountered, forms spores in high-salinity environments. Understanding these nuances can help predict sporulation behavior based on the bacterium’s ecological niche. For instance, if you’re analyzing soil samples, *Bacillus* and *Sporosarcina* are more likely candidates than *Clostridium*.

In conclusion, checking the genus and species is a critical first step in determining spore-forming potential. However, it’s not the only step. Combining this information with laboratory techniques like staining, culturing, and environmental context provides a comprehensive assessment. For example, if you identify *Clostridium perfringens* in a food sample, knowing its spore-forming nature can guide appropriate heat treatment (e.g., 121°C for 15 minutes in an autoclave) to ensure food safety. This multi-faceted approach ensures accuracy and practicality in identifying spore-forming bacteria.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Easily Sign Up for Spore

You may want to see also

Observe colony morphology: Spore-formers may show irregular or wrinkled colony edges on agar plates

Colony morphology on agar plates offers a visual clue to whether a bacterium is a spore-former. Unlike the smooth, uniform edges typical of non-spore-forming bacteria, spore-formers often exhibit irregular or wrinkled colony margins. This phenomenon arises from the unique growth pattern of these bacteria. As the vegetative cells multiply, the spores, being more resistant and slower to germinate, create a uneven expansion at the colony's edge. This distinct feature serves as a preliminary indicator, prompting further investigation into the bacterium's spore-forming capabilities.

To effectively observe this characteristic, prepare agar plates with nutrient-rich media suitable for bacterial growth. Inoculate the plates with the bacterial sample and incubate at the optimal temperature for the suspected species, typically around 37°C for many common bacteria. After 24 to 48 hours, examine the colonies under proper lighting. Look for edges that appear jagged, ruffled, or wavy, as opposed to the smooth, rounded edges of non-spore-formers. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis*, a well-known spore-former, often displays colonies with a distinctive, irregular perimeter.

While colony morphology is a useful initial screening tool, it is not definitive. False positives can occur with certain non-spore-forming bacteria that produce similar colony textures due to other factors, such as polysaccharide production. Conversely, some spore-formers may not always exhibit wrinkled edges, especially under suboptimal growth conditions. Therefore, follow up with additional tests, such as spore staining or heat resistance assays, to confirm spore formation.

Practical tips for enhancing observation include using a magnifying glass or a stereo microscope to better visualize the colony edges. Additionally, comparing the test colonies with known spore-forming and non-spore-forming controls on the same plate can provide a clearer contrast. For educational or research purposes, document the colony morphology with photographs or detailed sketches, noting specific features like the degree of wrinkling or irregularity. This approach not only aids in identification but also contributes to a comprehensive understanding of bacterial behavior.

Do Mold Spores Survive Winter? Uncovering Seasonal Mold Behavior

You may want to see also

Test for dormancy: Spores remain dormant in harsh conditions, reactivating when conditions improve

Spores are nature's survival capsules, designed to withstand extreme conditions that would kill their vegetative counterparts. This remarkable ability to enter a state of dormancy is a key characteristic of spore-forming bacteria, allowing them to persist in environments where nutrients are scarce, temperatures are extreme, or desiccation is a constant threat. Understanding this dormancy mechanism is crucial for identifying spore-forming bacteria and appreciating their ecological and practical implications.

The Dormancy Test: A Practical Approach

To test for spore dormancy, a simple yet effective method involves subjecting bacterial samples to harsh conditions, such as high temperatures or nutrient deprivation, followed by an assessment of their viability upon return to favorable conditions. For instance, heating a bacterial suspension at 80°C for 10 minutes will kill most vegetative cells but leave spores unharmed. Subsequently, plating the heated sample onto nutrient-rich agar and incubating it at 37°C for 24-48 hours will reveal the presence of spore-forming bacteria if colonies emerge. This test, known as the thermal death time (TDT) assay, is a standard procedure in microbiology laboratories.

Comparative Analysis: Dormancy vs. Vegetative Growth

In contrast to vegetative cells, which require a constant supply of nutrients and favorable environmental conditions to grow and divide, spores can remain dormant for years, even decades, without any metabolic activity. This quiescent state is characterized by a significant reduction in water content, a thickened cell wall, and the presence of dipicolinic acid, a unique chemical marker of spores. When conditions improve, spores germinate, shedding their protective coat and resuming vegetative growth. This transformation is rapid, often occurring within minutes to hours, and can be triggered by specific nutrients, changes in pH, or temperature shifts.

Practical Implications and Applications

The ability to form spores has significant implications in various fields, including food safety, healthcare, and environmental science. In the food industry, spore-forming bacteria like *Clostridium botulinum* and *Bacillus cereus* are major concerns, as they can survive food processing and cause illness upon ingestion. Understanding spore dormancy helps develop effective sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15-30 minutes, which ensures the destruction of spores. In healthcare, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* pose challenges in hospital settings, requiring rigorous disinfection protocols to prevent outbreaks.

Tips for Identifying Spore-Forming Bacteria

For researchers and enthusiasts, identifying spore-forming bacteria can be facilitated by combining the dormancy test with other methods. Microscopic examination using a phase-contrast or fluorescence microscope can reveal the presence of spores, which appear as refractile, oval-shaped bodies within or outside the vegetative cells. Additionally, molecular techniques like PCR targeting spore-specific genes, such as *spo0A* or *cotA*, provide a rapid and sensitive means of detection. By integrating these approaches, one can confidently determine whether a bacterium is spore-forming and better understand its ecological role and potential risks.

Effective Milky Spore Preparation: A Step-by-Step Guide for Gardeners

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spore-forming bacteria typically belong to the genus *Bacillus* or *Clostridium*. Key characteristics include the presence of endospores, which are highly resistant, dormant structures formed within the bacterial cell. These spores can survive extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and desiccation. Microscopic examination often reveals oval or cylindrical spores within the bacterial cell.

To confirm spore formation, perform a spore stain (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton stain), which differentiates spores from vegetative cells. Additionally, a heat treatment (e.g., 80°C for 10 minutes) can be applied to kill vegetative cells while leaving spores intact. Subsequent culturing on nutrient agar will show growth only if spores were present.

Yes, methods like the most probable number (MPN) or pour plate techniques can be used to detect spore-forming bacteria in environmental samples. PCR targeting spore-specific genes (e.g., *spo0A* in *Bacillus*) can also provide molecular confirmation. Additionally, heat or chemical resistance assays can help identify spore-forming bacteria by their ability to survive harsh conditions.