*Clostridium tetani*, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, is indeed a spore-forming organism. This characteristic is crucial to its survival and pathogenicity. Under unfavorable environmental conditions, such as nutrient depletion or exposure to harsh conditions, *C. tetani* can differentiate into highly resistant endospores. These spores are metabolically dormant and can withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and many disinfectants, allowing the bacterium to persist in soil and other environments for extended periods. When spores enter a suitable host, such as through a wound, they germinate into vegetative cells, which then produce the potent neurotoxin tetanospasmin, causing the symptoms of tetanus. This spore-forming ability is a key factor in the bacterium's ability to cause disease and its widespread presence in the environment.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Spore Formation | Yes |

| Spore Location | Terminal (forms at one end of the cell) |

| Spore Shape | Oval or round |

| Spore Function | Survival in harsh conditions (e.g., heat, desiccation, chemicals) |

| Spore Resistance | Highly resistant to environmental stresses |

| Vegetative Form | Rod-shaped, gram-positive, anaerobic bacterium |

| Habitat | Soil, dust, animal feces, gastrointestinal tract of animals and humans |

| Disease Caused | Tetanus (via production of tetanospasmin toxin) |

| Toxin Production | Tetanospasmin (potent neurotoxin causing muscle stiffness and spasms) |

| Oxygen Tolerance | Strict anaerobe (cannot survive in the presence of oxygen) |

| Motility | Motile (possesses flagella for movement) |

| Endospore Stain | Positive (stains with specific spore-specific dyes) |

What You'll Learn

- Spore Formation Process: C. tetani forms spores under stress, ensuring survival in harsh conditions

- Spore Structure: Spores have a thick, protective coat resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation

- Germination Triggers: Spores germinate in favorable environments, such as deep tissue wounds

- Clinical Relevance: Spores cause tetanus when they germinate and produce tetanospasmin toxin

- Survival Mechanism: Spore formation allows C. tetani to persist in soil and gut environments

Spore Formation Process: C. tetani forms spores under stress, ensuring survival in harsh conditions

Under adverse conditions, *Clostridium tetani* initiates a remarkable survival mechanism: spore formation. This process, known as sporulation, is a highly regulated, energy-intensive transformation that converts the bacterium into a dormant, resilient spore. Unlike its vegetative form, the spore is resistant to extreme temperatures, desiccation, and chemical disinfectants, ensuring the organism’s persistence in environments hostile to life. For *C. tetani*, this adaptation is critical, as it thrives in soil and animal intestines but must endure periods of nutrient deprivation and exposure to external stressors.

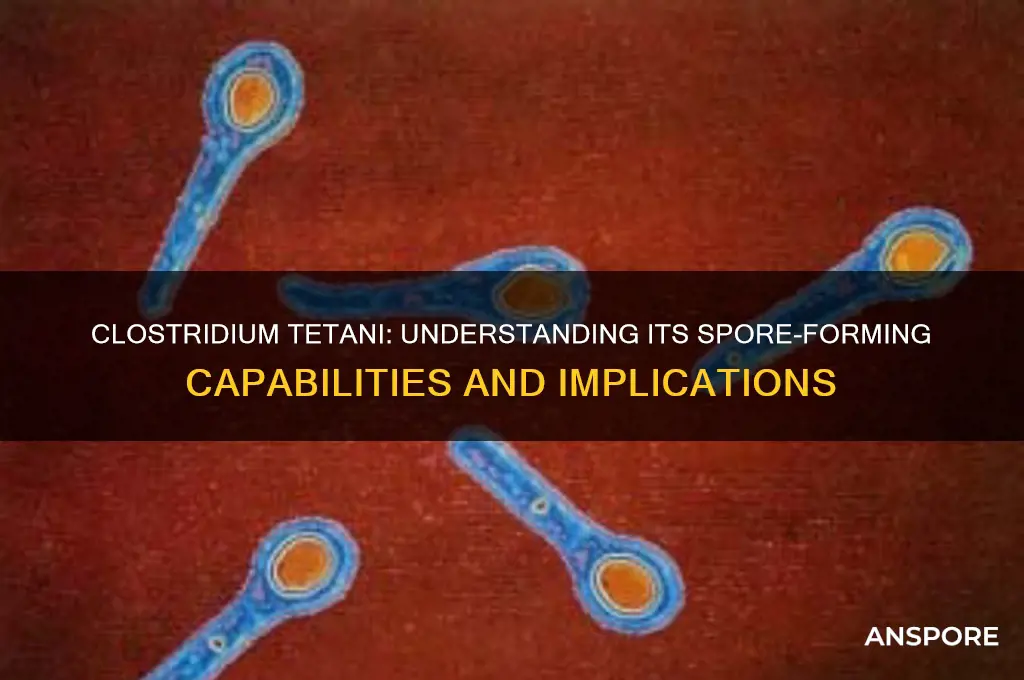

The sporulation process begins when *C. tetani* detects environmental cues such as nutrient depletion or oxygen exposure. In response, the bacterium asymmetrically divides, forming a larger mother cell and a smaller forespore. The mother cell then engulfs the forespore, creating a protective environment for the developing spore. Within this compartment, the forespore undergoes a series of morphological changes, including the synthesis of a thick, multilayered coat and the accumulation of dipicolinic acid, a molecule that stabilizes the spore’s DNA. This intricate process takes several hours to complete, culminating in the release of a mature spore capable of surviving for years.

From a practical standpoint, understanding *C. tetani*’s sporulation process has significant implications for infection prevention. Spores can contaminate wounds, particularly those exposed to soil, and germinate into vegetative cells under favorable conditions, leading to tetanus. Unlike vegetative cells, spores are not easily eradicated by routine cleaning or even boiling water; they require autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes or specialized chemical agents like hydrogen peroxide to be neutralized. This underscores the importance of thorough wound cleaning and vaccination, as the tetanus toxoid vaccine provides immunity against the toxin produced by vegetative *C. tetani*.

Comparatively, *C. tetani*’s sporulation process shares similarities with other spore-forming bacteria, such as *Bacillus anthracis* and *Clostridium botulinum*, but its ecological niche and pathogenic mechanism are distinct. While *B. anthracis* spores are primarily transmitted through inhalation or contact, *C. tetani* spores enter the body via wounds, emphasizing the need for context-specific prevention strategies. For instance, agricultural workers and gardeners, who frequently encounter soil, should wear protective gloves and ensure tetanus vaccination is up to date, with booster doses recommended every 10 years or after a high-risk injury.

In conclusion, *C. tetani*’s ability to form spores under stress is a testament to its evolutionary ingenuity. This process not only ensures the bacterium’s survival in harsh conditions but also poses a persistent threat to human health. By understanding the sporulation mechanism and its practical implications, we can better mitigate the risk of tetanus through targeted prevention measures, from wound care to vaccination protocols. This knowledge bridges the gap between microbiology and public health, offering actionable insights for both clinicians and at-risk populations.

Alcohol vs. Mildew: Can It Effectively Kill Spores?

You may want to see also

Spore Structure: Spores have a thick, protective coat resistant to heat, chemicals, and radiation

Spores, the dormant forms of certain bacteria, owe their resilience to a thick, protective coat that acts as an impenetrable fortress. This coat, composed of multiple layers including an outer exosporium, a spore coat, and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan, provides unparalleled resistance to extreme conditions. For instance, *Clostridium tetani*, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, forms spores that can survive boiling water (100°C) for several minutes, withstand exposure to harsh chemicals like ethanol and bleach, and remain viable after prolonged radiation exposure. This structural robustness ensures the bacterium’s survival in hostile environments, making it a formidable pathogen.

To understand the spore’s durability, consider its layered defense mechanism. The outermost exosporium acts as a barrier against enzymes and chemicals, while the spore coat, rich in keratin-like proteins, provides mechanical strength and resistance to heat. Beneath this lies the cortex, which contains dipicolinic acid—a molecule that binds calcium ions to stabilize the spore’s DNA and proteins against radiation and desiccation. This multi-layered design is not just a passive shield but an active system that preserves the bacterium’s genetic material and metabolic machinery until conditions improve.

Practical implications of spore resistance are evident in medical and industrial settings. For example, sterilizing surgical instruments requires autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes to ensure *C. tetani* spores are destroyed. In agriculture, soil contaminated with these spores remains a persistent threat to livestock and humans, as the spores can survive for decades. To mitigate risk, wound cleaning with hydrogen peroxide or iodine-based solutions is recommended to neutralize spores before they germinate and produce tetanospasmin, the toxin responsible for tetanus.

Comparatively, the spore structure of *C. tetani* contrasts with non-spore-forming bacteria, which lack such protective mechanisms and are more easily eradicated by standard disinfection methods. This highlights the evolutionary advantage of sporulation, allowing bacteria like *C. tetani* to persist in diverse environments, from soil to hospital surfaces. Understanding this structure is crucial for developing targeted strategies to combat spore-forming pathogens, such as advanced sterilization techniques or spore-specific antimicrobial agents.

In conclusion, the spore’s thick, protective coat is a marvel of biological engineering, enabling *C. tetani* to endure conditions that would destroy most life forms. This resilience underscores the importance of rigorous sterilization protocols and proactive wound management to prevent tetanus. By studying spore structure, we gain insights into both the bacterium’s survival strategies and the measures needed to counteract them, ensuring safer environments and better health outcomes.

Stun Spore vs. Electric Types: Does It Work in Pokémon Battles?

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Spores germinate in favorable environments, such as deep tissue wounds

Spores of *Clostridium tetani*, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in soil, dust, and even animal feces for years. However, their true danger lies in their ability to germinate when introduced into a favorable environment, such as a deep tissue wound. This transformation from dormant spore to active, toxin-producing bacterium is triggered by specific conditions that mimic the nutrient-rich, anaerobic surroundings of damaged tissue.

Understanding the Germination Process:

When *C. tetani* spores enter a wound, they sense environmental cues that signal the presence of a suitable habitat. Key triggers include warmth (optimal at 37°C, human body temperature), moisture, and the absence of oxygen. Additionally, the presence of certain nutrients, such as amino acids and sugars, which leak from damaged cells, further stimulate germination. This process is not instantaneous; it requires time, typically hours to days, depending on the wound’s conditions. For instance, a puncture wound, which creates a deep, oxygen-poor environment, is particularly conducive to spore activation.

Practical Implications for Wound Care:

To prevent tetanus, it’s crucial to treat wounds promptly and thoroughly. Clean all wounds with soap and water, removing debris and foreign material. For deeper or contaminated wounds, seek medical attention immediately. Healthcare providers may administer a tetanus booster if your last vaccination was more than 5–10 years ago, depending on the wound’s severity. For example, a rusty nail puncture warrants urgent care, as it carries a high risk of introducing *C. tetani* spores into a spore-friendly environment.

Comparative Perspective:

Unlike other spore-forming bacteria, such as *Clostridium botulinum*, which germinates in conditions like canned food, *C. tetani* is uniquely adapted to exploit tissue damage. This specificity highlights the importance of wound management in preventing tetanus. While *C. botulinum* thrives in low-oxygen, nutrient-rich environments like improperly preserved food, *C. tetani* spores remain dormant until they encounter the unique conditions of a deep wound. This distinction underscores why tetanus is often associated with injuries like punctures, burns, or surgical sites.

Takeaway for Prevention:

Staying up-to-date with tetanus vaccinations is the most effective way to prevent the disease. The CDC recommends a tetanus booster every 10 years for adults, with additional doses after high-risk wounds. For children, the DTaP vaccine series (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis) is administered at 2, 4, 6, and 15–18 months, followed by a booster at 4–6 years. By combining vaccination with proper wound care, you can significantly reduce the risk of *C. tetani* spores germinating and causing tetanus. Remember, spores are ubiquitous, but their activation is preventable.

Do Daisies Have Spores? Unveiling the Truth About Daisy Reproduction

You may want to see also

Clinical Relevance: Spores cause tetanus when they germinate and produce tetanospasmin toxin

Clostridium tetani, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, is indeed a spore-former, and this characteristic is central to its pathogenicity. Spores are highly resistant structures that allow the bacterium to survive in harsh environments, such as soil, for extended periods. When these spores enter the body through wounds, they can germinate under favorable conditions, transforming into active, toxin-producing cells. This process is the critical first step in the development of tetanus, a severe and often fatal disease characterized by muscle stiffness and spasms.

The clinical relevance of C. tetani spores lies in their ability to produce tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin, once they germinate. Tetanospasmin interferes with the normal function of motor neurons, leading to uncontrolled muscle contractions. For instance, a puncture wound contaminated with soil containing C. tetani spores can introduce the bacterium into deep tissues, where the anaerobic environment promotes spore germination. Within 24 to 72 hours, the toxin begins to affect the nervous system, causing symptoms like jaw stiffness (trismus), difficulty swallowing, and generalized muscle rigidity. Prompt recognition of such wounds and appropriate wound care, including thorough cleaning and tetanus vaccination if necessary, are essential to prevent spore germination and toxin production.

From a preventive perspective, understanding the spore-forming nature of C. tetani underscores the importance of tetanus vaccination. The tetanus toxoid vaccine primes the immune system to neutralize tetanospasmin before it can cause harm. Adults should receive a tetanus booster every 10 years, while children follow a schedule of doses starting at 2 months of age. In the event of a high-risk wound, such as a deep puncture or one contaminated with dirt, a booster may be recommended even if fewer than 10 years have passed since the last dose. This proactive approach minimizes the risk of spores germinating and producing toxin, effectively preventing tetanus.

Comparatively, other spore-forming pathogens like Clostridium botulinum (causative agent of botulism) also rely on spore germination to produce toxins, but the clinical manifestations and transmission routes differ. While botulism typically results from ingesting preformed toxin in contaminated food, tetanus requires spore entry through wounds. This distinction highlights the unique clinical relevance of C. tetani spores: their ability to cause disease is directly tied to their germination in specific environments within the body. Recognizing this mechanism allows healthcare providers to tailor interventions, such as wound management and vaccination, to disrupt the spore-to-toxin pathway effectively.

In summary, the spore-forming capability of C. tetani is not merely a biological curiosity but a key factor in its clinical relevance. Spores serve as the dormant vehicles that deliver the bacterium to susceptible sites, where germination and toxin production initiate tetanus. Practical measures, including proper wound care and adherence to vaccination schedules, are critical to preventing spore activation and the subsequent release of tetanospasmin. By focusing on these specifics, healthcare professionals and individuals can mitigate the risk of this potentially deadly disease.

Unlock Spore's Flora Editor: A Step-by-Step Guide for Beginners

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanism: Spore formation allows C. tetani to persist in soil and gut environments

Clostridium tetani, the bacterium responsible for tetanus, is indeed a spore-former, and this ability is central to its survival in harsh environments. Spore formation is a sophisticated survival mechanism that allows C. tetani to endure conditions that would otherwise be lethal to its vegetative form. These spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals, enabling the bacterium to persist in soil for decades. This resilience is particularly crucial in agricultural settings, where soil contamination with C. tetani spores is common due to the presence of animal feces. Understanding this mechanism is essential for implementing effective sanitation practices, such as proper wound cleaning and tetanus vaccination, to prevent infection.

In the gut environment, spore formation serves a dual purpose for C. tetani. While the gut is a dynamic and nutrient-rich habitat, it is also subject to fluctuations in pH, oxygen levels, and antimicrobial defenses. Spores allow the bacterium to remain dormant until conditions become favorable for germination and growth. This adaptability is particularly advantageous in the gastrointestinal tracts of herbivores, where C. tetani can coexist with other microbiota without being outcompeted. For humans, this highlights the importance of maintaining a healthy gut microbiome, as disruptions (e.g., from antibiotic use) could create opportunities for C. tetani spores to germinate and potentially cause harm.

From a practical standpoint, the spore-forming ability of C. tetani has significant implications for medical and agricultural practices. For instance, thorough wound cleaning with antiseptics like hydrogen peroxide or povidone-iodine can help eliminate spores before they germinate. Tetanus vaccination, which provides protective immunity by neutralizing the toxin produced by C. tetani, remains the most effective preventive measure. In agriculture, reducing soil contamination through proper manure management and avoiding deep puncture wounds from contaminated tools can minimize exposure to spores. These strategies underscore the importance of targeting the spore stage of C. tetani to prevent tetanus.

Comparatively, the spore-forming capability of C. tetani sets it apart from non-spore-forming pathogens, which typically rely on immediate host invasion or short-term environmental persistence. Unlike bacteria such as E. coli or Salmonella, which are vulnerable to environmental stresses, C. tetani spores can remain viable in soil and gut environments for extended periods, waiting for the right conditions to strike. This distinction emphasizes the need for a spore-centric approach in controlling C. tetani, rather than relying solely on measures targeting its vegetative form. By focusing on spore prevention and inactivation, we can more effectively mitigate the risk of tetanus.

Finally, the spore formation of C. tetani serves as a remarkable example of microbial adaptability, showcasing how bacteria evolve to thrive in diverse and challenging environments. This mechanism not only ensures the bacterium’s survival but also poses a persistent threat to human and animal health. For individuals, especially those in high-risk occupations like farming or gardening, awareness of this survival strategy is critical. Regular tetanus booster shots (every 10 years or after a deep wound) and prompt wound care are essential preventive measures. By understanding and addressing the spore-forming nature of C. tetani, we can better protect ourselves from this resilient pathogen.

Do Algae Reproduce by Spores? Unveiling Aquatic Plant Reproduction Secrets

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, Clostridium tetani is a spore-forming bacterium.

Clostridium tetani forms spores in response to adverse environmental conditions, such as nutrient depletion or oxygen exposure.

Yes, the spores of Clostridium tetani are highly resistant to environmental stresses and can survive in soil for years, posing a risk of infection if they enter the body.

Tetanus disease occurs when spores of Clostridium tetani germinate in a wound, allowing the bacteria to produce a potent neurotoxin that causes muscle stiffness and spasms.