Determining whether a mushroom is poisonous is a critical concern for foragers, gardeners, and nature enthusiasts alike, as misidentification can lead to severe health risks or even fatalities. With thousands of mushroom species worldwide, many of which closely resemble one another, distinguishing between edible and toxic varieties requires careful observation of key characteristics such as color, shape, gills, spores, and habitat. While some poisonous mushrooms, like the infamous Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*), exhibit telltale signs, others may lack obvious warnings, making reliance on folklore or superficial traits unreliable. Consulting expert guides, using spore print tests, or seeking advice from mycologists are essential steps to ensure safety, as even experienced foragers can make mistakes. When in doubt, the golden rule is simple: if you’re not 100% certain, don’t eat it.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Common Poisonous Mushrooms: Identify deadly species like Death Cap, Destroying Angel, and Conocybe

- Edible Lookalikes: Beware of toxic doubles resembling chanterelles, morels, or puffballs

- Symptoms of Poisoning: Recognize nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, or skin irritation

- Safe Foraging Tips: Stick to known species, consult experts, and avoid unfamiliar mushrooms

- Testing Myths: Ignore DIY tests; only lab analysis confirms toxicity accurately

Common Poisonous Mushrooms: Identify deadly species like Death Cap, Destroying Angel, and Conocybe

The Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) is often called the "silent killer" because its symptoms can take 6–24 hours to appear after ingestion. By then, its amatoxins have already caused severe liver and kidney damage. Found in North America, Europe, and Australia, it resembles edible species like the Paddy Straw mushroom, making misidentification common. A single Death Cap contains enough toxin to kill an adult, and there’s no antidote—only supportive care. If you suspect ingestion, seek medical help immediately and bring a sample of the mushroom for identification.

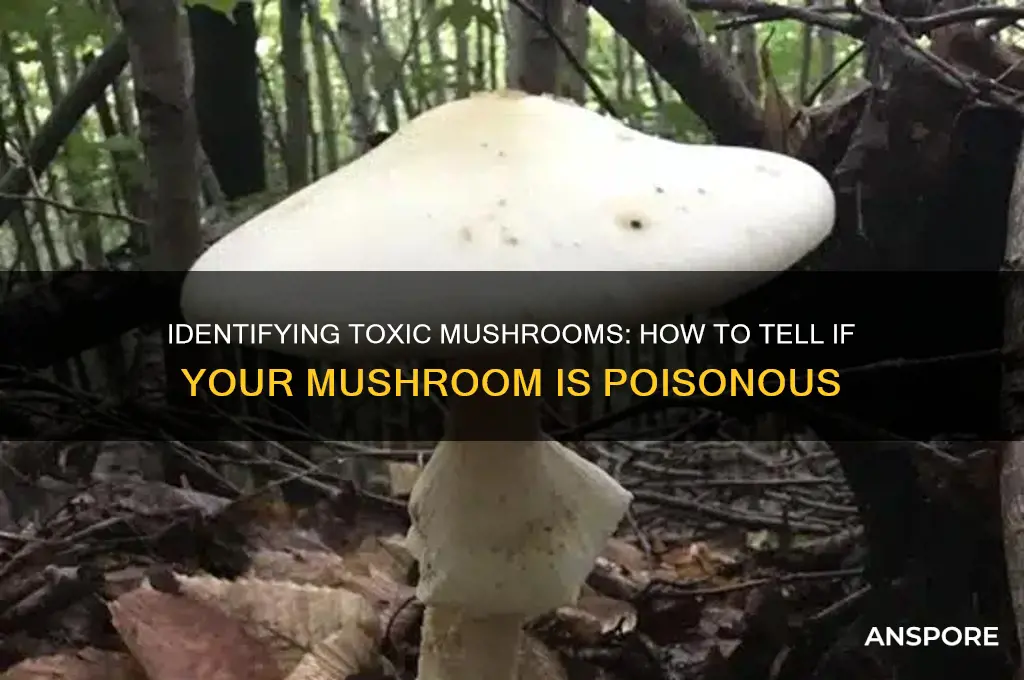

Destroying Angels (*Amanita bisporigera*, *A. ocreata*, and others) are deceptively beautiful, with pure white caps and stems that mimic edible button mushrooms. Their amatoxins act similarly to the Death Cap’s, causing delayed symptoms like vomiting, diarrhea, and organ failure. Unlike the Death Cap, Destroying Angels are primarily found in North America and often grow near oak trees. A fatal dose is just 10–20 grams, roughly one mushroom. Always avoid white-gilled mushrooms unless you’re an expert, as even experienced foragers mistake these species.

Conocybe species, particularly *Conocybe filaris*, are less known but equally dangerous. These small, brown mushrooms contain the toxin phallotoxin, which causes gastrointestinal distress within 30 minutes to 2 hours. Found in lawns and gardens across North America and Europe, they’re often overlooked due to their size. While less lethal than the Death Cap, Conocybe poisoning can still lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, especially in children or pets. If ingested, induce vomiting and seek medical attention promptly.

To avoid these deadly species, follow these practical tips: never eat a wild mushroom unless identified by an expert, carry a field guide with color photos, and note the mushroom’s habitat (e.g., near oaks or in lawns). If in doubt, throw it out. Remember, no single rule—like "poisonous mushrooms taste bad" or "animals avoid them"—is foolproof. When foraging, prioritize safety over curiosity, as even a small mistake can have fatal consequences.

Are Coral Mushrooms Safe? Identifying Poisonous Varieties and Edible Ones

You may want to see also

Edible Lookalikes: Beware of toxic doubles resembling chanterelles, morels, or puffballs

The forest floor is a treasure trove for foragers, but it's also a minefield of deception. Among the prized chanterelles, morels, and puffballs lurk their toxic doppelgängers, mushrooms that mimic these delicacies in shape, color, or habitat. Misidentification can lead to severe consequences, from gastrointestinal distress to organ failure. Knowing the subtle differences between these lookalikes is not just a skill—it's a survival necessity.

Take the chanterelle, for instance, with its golden, forked gills and fruity aroma. Its toxic double, the jack-o’-lantern (Omphalotus olearius), shares a similar bright orange hue but has true gills and a sharp, acrid smell. Ingesting even a small amount of the jack-o’-lantern can cause vomiting, diarrhea, and dehydration within 30 minutes to 2 hours. To avoid this, always check for forked gills and a pleasant scent in chanterelles. If in doubt, skip it—no meal is worth a trip to the emergency room.

Morels, with their honeycomb caps, are another forager favorite, but they have a sinister twin: the false morel (Gyromitra esculenta). False morels have a brain-like, wrinkled cap and grow in similar wooded areas. They contain gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine in the body, causing symptoms like nausea, dizziness, and even seizures in severe cases. Proper preparation—soaking, boiling, and discarding the water—can reduce toxicity, but it’s risky. Foraging experts advise sticking to true morels and leaving false morels untouched.

Puffballs, often considered foolproof due to their distinctive spherical shape, also have a dangerous lookalike: the Amanita ocreata, or “death angel.” Young death angels can resemble small, white puffballs before their caps open. A single bite can cause liver and kidney failure within 24–48 hours, often with no initial symptoms. To identify a true puffball, cut it in half—it should be solid and uniform inside. Any signs of gills or a developing cap indicate a different species and should be discarded immediately.

The key to safe foraging lies in meticulous observation and skepticism. Carry a field guide, use a magnifying glass to examine spore colors, and consult experienced foragers. Remember, toxic mushrooms often thrive in the same environments as their edible counterparts, so location alone is not a reliable indicator. When in doubt, throw it out—your health is not worth the gamble.

Are Garden Mushrooms Safe to Touch? Debunking Toxicity Myths

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning: Recognize nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, organ failure, or skin irritation

Nausea and vomiting are often the body’s first alarm bells when it detects toxins from poisonous mushrooms. These symptoms typically appear within 20 minutes to 4 hours after ingestion, depending on the type of mushroom and the amount consumed. For instance, *Amanita phalloides* (Death Cap) can cause severe gastrointestinal distress as its toxins begin to disrupt cellular function. If you or someone you know experiences sudden, unexplained nausea or vomiting after consuming wild mushrooms, seek medical attention immediately. Time is critical, as delayed treatment can lead to more severe complications.

Hallucinations are a hallmark of poisoning by psychoactive mushrooms, such as those containing psilocybin or muscarine. While some may seek these effects intentionally, accidental ingestion can lead to confusion, paranoia, or visual distortions. Children are particularly vulnerable, as even small doses can trigger intense reactions. For example, *Clitocybe dealbata* (Ivory Funnel) can cause sweating, blurred vision, and hallucinations within 15–30 minutes of consumption. If hallucinations occur, keep the individual calm, monitor their breathing, and call poison control for guidance.

Organ failure is the most severe and life-threatening symptom of mushroom poisoning, often associated with species like *Amanita ocreata* or *Galerina marginata*. These mushrooms contain amatoxins, which target the liver and kidneys, leading to symptoms like jaundice, abdominal pain, and dark urine within 6–24 hours. In severe cases, liver failure can occur within 3–5 days, requiring immediate hospitalization and, in some cases, a liver transplant. Elderly individuals or those with pre-existing liver conditions are at higher risk. If organ failure is suspected, administer activated charcoal (if advised by a professional) to reduce toxin absorption, but do not induce vomiting without guidance.

Skin irritation, though less common, can signal mushroom toxicity, particularly with species like *Dacrymyces palmatus* or contact with certain fungi. Symptoms include redness, itching, or blistering at the site of contact. While not typically life-threatening, it can indicate the presence of harmful compounds. If skin irritation occurs after handling mushrooms, wash the affected area thoroughly with soap and water. For persistent reactions, apply a corticosteroid cream or seek medical advice. Always wear gloves when handling wild mushrooms, especially if you’re unsure of their identity.

Recognizing these symptoms early can be the difference between a minor scare and a medical emergency. Keep a sample of the mushroom for identification, note the time of ingestion, and contact a healthcare provider or poison control center immediately. Remember, not all poisonous mushrooms cause immediate symptoms, so vigilance is key. When in doubt, avoid consumption altogether—some toxins are irreversible, and misidentification can be fatal.

Are Mushrooms Safe for Puppies? Poison Risks and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$23.49 $39.95

Safe Foraging Tips: Stick to known species, consult experts, and avoid unfamiliar mushrooms

Foraging for mushrooms can be a rewarding hobby, but it’s a minefield for the uninitiated. Over 14,000 mushroom species exist worldwide, and misidentification can lead to severe poisoning or even death. The *Death Cap* (Amanita phalloides), for instance, resembles edible species like the Paddy Straw mushroom but contains toxins that cause liver failure within 48 hours. Stick to known species you’ve positively identified multiple times, and always cross-reference with reliable field guides or apps like iNaturalist. One mistake can outweigh a lifetime of safe foraging.

Consulting experts isn’t just a suggestion—it’s a necessity. Mycological societies and local foraging groups offer workshops where experienced foragers can verify your finds. For example, the North American Mycological Association hosts identification sessions where members bring specimens for collective analysis. Even if you’re confident, submitting photos to online forums like Reddit’s r/mycology can provide a second opinion. Remember, no app or guide is foolproof; human expertise remains the gold standard.

Unfamiliar mushrooms are the siren songs of the forest, tempting with their novelty but often hiding danger. Take the *False Morel* (Gyromitra spp.), which resembles true morels but contains gyromitrin, a toxin that converts to monomethylhydrazine—a component of rocket fuel. Even cooking doesn’t always neutralize it. If you’re unsure, leave it alone. The rule of thumb is simple: if you can’t identify it with 100% certainty, don’t eat it. Curiosity killed the cat, and it could land you in the emergency room.

Practical tips can further safeguard your foraging adventures. Always carry a knife and basket (not a plastic bag, which can cause spoilage) and cut mushrooms at the base to preserve the mycelium. Note the habitat—some species, like the *Chanterelle*, thrive in specific ecosystems, while others, like the *Destroying Angel*, lurk in deciduous forests. For beginners, start with easily identifiable species like *Lion’s Mane* or *Oyster mushrooms*, which have few toxic look-alikes. Finally, never consume wild mushrooms raw, as many contain toxins neutralized by cooking. Foraging is a skill honed over years, not days—respect the learning curve.

Identifying Yard Mushrooms: Are Little White Varieties Poisonous?

You may want to see also

Testing Myths: Ignore DIY tests; only lab analysis confirms toxicity accurately

DIY mushroom toxicity tests are a dangerous gamble. Many online sources claim rubbing a mushroom on a silver spoon, observing insect activity, or noting color changes can indicate edibility. These methods are not only unreliable but can lead to fatal mistakes. For instance, the "silver spoon test" is based on the outdated belief that toxic mushrooms turn silver utensils black—a myth with no scientific basis. Similarly, some poisonous mushrooms, like the deadly Galerina marginata, are consumed by insects without harm, debunking the "insect test." Relying on such methods can have severe consequences, as misidentification can lead to organ failure, neurological damage, or death.

Laboratory analysis remains the gold standard for determining mushroom toxicity. Professional mycologists use advanced techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry to identify toxic compounds such as amatoxins, orellanine, or muscarine. These methods can detect even trace amounts of toxins, ensuring accurate results. For example, a single Amanita phalloides mushroom contains enough amatoxins to cause liver failure in an adult, yet its appearance can mimic edible species like the Paddy Straw mushroom. Without lab testing, visual identification alone is insufficient and risky.

Attempting DIY tests not only wastes time but also creates a false sense of security. Consider the "taste test," where some claim a bitter mushroom is poisonous. However, toxic mushrooms like the Destroying Angel (Amanita bisporigera) are often flavorless, while some edible species can taste bitter due to environmental factors. Similarly, the "24-hour rule"—assuming a mushroom is safe if it doesn’t cause symptoms within a day—is flawed, as toxins like those in Cortinarius species can take days to manifest symptoms. These misconceptions highlight the need for professional evaluation.

Practical steps to ensure safety include documenting the mushroom’s appearance (cap, gills, stem, and spore color), habitat, and season before submitting a sample to a lab. Avoid handling mushrooms with bare hands, as some toxins can be absorbed through the skin. If ingestion has occurred, immediately contact a poison control center or emergency services, providing details about the mushroom and symptoms. While apps and field guides can aid identification, they should never replace lab analysis. The takeaway is clear: when in doubt, throw it out—and always seek expert verification.

Are Toadstool Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? A Pet Owner's Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Unfortunately, there’s no single rule or visual characteristic that guarantees a mushroom is safe or poisonous. Some toxic mushrooms resemble edible ones, and vice versa. Always consult a field guide or expert for identification.

No, bright colors do not always indicate toxicity. Some edible mushrooms are brightly colored, while some poisonous ones are plain. Color alone is not a reliable indicator of safety.

No, these methods are myths and unreliable. Silverware does not change color with toxic mushrooms, and animals may eat poisonous mushrooms without immediate harm, but this does not mean they are safe for humans.

Seek medical attention immediately, even if symptoms haven’t appeared. Bring a sample of the mushroom (if possible) for identification. Do not wait for symptoms to worsen.