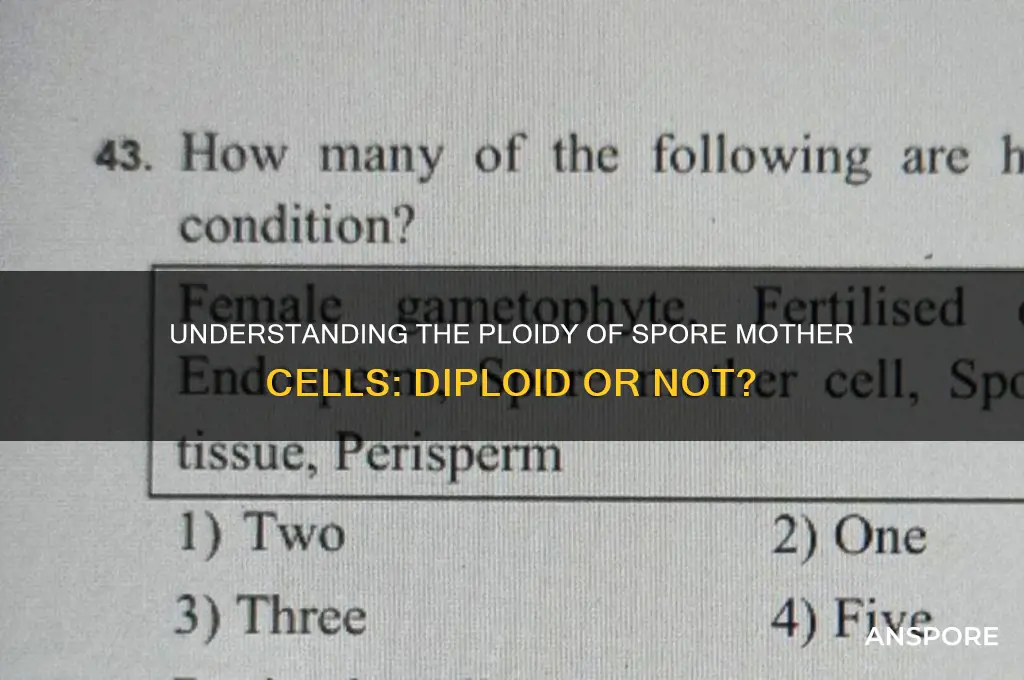

The question of whether the spore mother cell is diploid is central to understanding the life cycles of plants and fungi, particularly in organisms that undergo alternation of generations. In this context, the spore mother cell, also known as the sporocyte, plays a crucial role in the production of spores through meiosis. Since meiosis involves the reduction of the chromosome number from diploid (2n) to haploid (n), the ploidy of the spore mother cell is a key factor in determining the genetic makeup of the resulting spores. In most cases, the spore mother cell is indeed diploid, as it arises from the mitotic division of a diploid cell, ensuring that meiosis can proceed to produce haploid spores. This diploid nature is essential for maintaining the alternation of generations, where the sporophyte generation (diploid) gives rise to the gametophyte generation (haploid) through the formation of spores.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ploidy of Spore Mother Cell (SMC) | Diploid (2n) |

| Origin | Formed from the diploid microspore mother cell in sporophyte generation |

| Function | Undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid spores |

| Meiosis Outcome | Produces tetrad of haploid spores (n) |

| Genetic Composition | Contains two sets of chromosomes (one from each parent) |

| Role in Life Cycle | Part of the alternation of generations in plants (sporophyte phase) |

| Location in Plants | Found in sporangia of ferns, mosses, and seed plants |

| Significance | Essential for the production of gametophytes in the plant life cycle |

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Spore Mother Cell: Understand what a spore mother cell is and its role in reproduction

- Ploidy Levels in Fungi: Explore how ploidy varies in fungal spore mother cells during life cycles

- Meiosis in Spore Formation: Examine the meiotic process that reduces ploidy in spore mother cells

- Diploid vs. Haploid Stages: Compare diploid and haploid phases in organisms with spore mother cells

- Exceptions in Plant Life Cycles: Identify cases where spore mother cells deviate from typical diploid status

Definition of Spore Mother Cell: Understand what a spore mother cell is and its role in reproduction

The spore mother cell, a pivotal player in the reproductive strategies of plants and certain fungi, is a diploid cell that undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores. This process is fundamental to the alternation of generations, a life cycle characteristic of many organisms where diploid and haploid phases alternate. In plants like ferns and mosses, the spore mother cell is located within the sporangium, a structure dedicated to spore production. Understanding its diploid nature is crucial, as it ensures genetic diversity through meiosis, a reduction division that halves the chromosome number, setting the stage for the development of haploid spores.

To grasp the spore mother cell’s role, consider its function in ferns. After meiosis, each haploid spore grows into a gametophyte, a small, independent plant that produces gametes. This gametophyte phase is haploid, contrasting with the diploid sporophyte phase, which includes the spore mother cell. The cycle completes when gametes from the gametophyte unite to form a new sporophyte. This alternation ensures genetic recombination and adaptability, highlighting the spore mother cell’s critical role in bridging these phases. Its diploid status is non-negotiable, as it provides the genetic material necessary for meiosis and subsequent spore formation.

From a practical standpoint, identifying the spore mother cell in laboratory settings involves examining sporangia under a microscope. For students or researchers, staining techniques like the acetocarmine method can highlight the cell’s nucleus, confirming its diploid nature. In fungi, such as in the life cycle of bread mold (*Rhizopus*), the spore mother cell’s diploid state is similarly essential for producing spores that disperse and colonize new environments. This consistency across kingdoms underscores its evolutionary significance.

A comparative analysis reveals that while animals rely on gametes for reproduction, plants and fungi use spores as a dispersal mechanism. The spore mother cell’s diploid nature distinguishes it from gametes, which are haploid. This difference reflects the distinct reproductive strategies of these organisms. For instance, in mosses, the spore mother cell’s meiosis produces spores that can survive harsh conditions, ensuring species survival. This adaptability is a direct result of its diploid origin and subsequent reduction division.

In conclusion, the spore mother cell’s diploid status is central to its function in producing haploid spores through meiosis. This process is vital for genetic diversity and the alternation of generations in plants and fungi. Whether in ferns, mosses, or fungi, its role remains consistent, making it a cornerstone of reproductive biology. Understanding this cell’s nature not only clarifies its function but also highlights the elegance of evolutionary strategies in ensuring survival and diversity.

Installing Spore Without the Box: A Step-by-Step Digital Guide

You may want to see also

Ploidy Levels in Fungi: Explore how ploidy varies in fungal spore mother cells during life cycles

Fungi exhibit remarkable diversity in their life cycles, and ploidy levels in spore mother cells (SMCs) are a key aspect of this variation. Unlike plants and animals, where ploidy is often fixed, fungi can shift between haploid and diploid states, sometimes even existing in polyploid forms. This flexibility is crucial for their survival and adaptation to diverse environments. For instance, the model fungus *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* (baker’s yeast) alternates between haploid and diploid phases, with SMCs being diploid during sporulation. In contrast, filamentous fungi like *Aspergillus nidulans* maintain a haploid state throughout most of their life cycle, with SMCs also remaining haploid. Understanding these variations provides insights into fungal evolution and biotechnology applications, such as strain improvement for industrial processes.

To explore ploidy in fungal SMCs, consider the life cycle stages and environmental cues that trigger ploidy shifts. In basidiomycetes, such as mushrooms, SMCs are typically diploid, formed through karyogamy (nuclear fusion) before meiosis. This diploid phase ensures genetic diversity via recombination. However, in ascomycetes like *Neurospora crassa*, SMCs are haploid, and ploidy changes occur during sexual reproduction when haploid nuclei fuse. Environmental stressors, such as nutrient scarcity or temperature shifts, can also influence ploidy. For example, some yeast species increase ploidy under stress to enhance genetic robustness. Researchers use techniques like flow cytometry and DNA sequencing to measure ploidy, offering practical tools for studying these dynamics in the lab.

A comparative analysis of fungal SMC ploidy reveals evolutionary advantages. Diploid SMCs in basidiomycetes provide a buffer against deleterious mutations, as recessive alleles are masked. Haploid SMCs in ascomycetes, on the other hand, allow rapid adaptation through direct expression of beneficial mutations. Polyploidy, observed in species like *Candida albicans*, enhances stress tolerance and drug resistance, making it a concern in clinical settings. These strategies highlight fungi’s ability to balance stability and adaptability. For biotechnologists, manipulating ploidy levels in SMCs can optimize traits like enzyme production or secondary metabolite synthesis, as seen in penicillin-producing *Penicillium* strains.

Practical tips for studying ploidy in fungal SMCs include using synchronized cultures to track life cycle stages and applying genetic markers to monitor nuclear fusion events. For example, in *Schizosaccharomyces pombe*, a haploid fission yeast, researchers use fluorescent proteins to visualize nuclei during mating and sporulation. In industrial settings, controlling ploidy can improve fermentation efficiency; diploid yeast strains often exhibit higher ethanol tolerance in biofuel production. Caution is advised when inducing polyploidy, as it can lead to genomic instability. By integrating molecular biology and environmental control, scientists can harness ploidy variations to advance both fundamental research and applied fungal biotechnology.

Maximize Your Health Spore Count: Proven Strategies for Over 110

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Spore Formation: Examine the meiotic process that reduces ploidy in spore mother cells

Spore mother cells, the precursors to spores in plants and fungi, are indeed diploid, carrying two sets of chromosomes. This diploid state is crucial for the subsequent reduction in ploidy during meiosis, a specialized cell division process that ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in spore-producing organisms. Meiosis in spore formation is a finely orchestrated sequence of events that transforms a diploid mother cell into haploid spores, each genetically distinct and ready to develop under favorable conditions.

The meiotic process begins with the replication of DNA in the spore mother cell, ensuring that each chromosome consists of two identical sister chromatids. This preparatory phase, known as interphase, sets the stage for the two rounds of cell division that follow. During meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up, exchange genetic material through crossing over, and then segregate into two daughter cells. This reductional division halves the chromosome number, transitioning the cell from diploid to haploid. Meiosis II, an equational division, further separates the sister chromatids, resulting in four haploid spores. Each step is tightly regulated to prevent errors that could compromise spore viability or genetic integrity.

A key distinction in spore formation is the role of meiosis in reducing ploidy, as opposed to mitosis, which maintains ploidy. While mitosis produces genetically identical daughter cells, meiosis generates genetic diversity through crossing over and independent assortment. This diversity is essential for the survival of spore-producing organisms, enabling them to adapt to changing environments. For example, in ferns, the haploid spores dispersed from the sporophyte (diploid) generation can develop into gametophytes (haploid) that produce gametes, ensuring a life cycle that alternates between diploid and haploid phases.

Practical understanding of meiosis in spore formation has applications in agriculture and conservation. For instance, in breeding programs for crops like wheat or rice, knowledge of meiotic processes helps optimize hybridization strategies to enhance traits such as yield or disease resistance. Similarly, in preserving endangered plant species, manipulating spore formation through controlled environmental conditions can improve germination rates and seedling survival. To observe meiosis in spore mother cells, researchers often use techniques like chromosome staining and microscopy, providing visual evidence of the intricate divisions that underpin spore development.

In conclusion, the meiotic process in spore formation is a remarkable mechanism for reducing ploidy in diploid spore mother cells, ensuring genetic diversity and adaptability in spore-producing organisms. By understanding the steps, significance, and applications of this process, scientists and practitioners can harness its potential in fields ranging from botany to biotechnology. Whether in the lab or the field, the study of meiosis in spore formation remains a cornerstone of biological inquiry, offering insights into the fundamental processes that drive life’s complexity.

Surviving Extremes: How Spores Endure Dehydration and High Temperatures

You may want to see also

Diploid vs. Haploid Stages: Compare diploid and haploid phases in organisms with spore mother cells

In organisms that produce spore mother cells, the alternation between diploid and haploid phases is a cornerstone of their life cycle. The spore mother cell, a critical structure in this process, is typically diploid, containing two sets of chromosomes. This diploid state is essential for genetic diversity, as it allows for the recombination of genetic material during meiosis. For example, in ferns, the spore mother cell undergoes meiosis to produce haploid spores, which then grow into gametophytes—the haploid phase of the life cycle. This alternation ensures that both genetic stability and variability are maintained, a balance crucial for survival in changing environments.

Understanding the transition from diploid to haploid phases requires a closer look at the mechanisms involved. In the diploid phase, organisms focus on growth and resource accumulation, often in the form of sporophytes. When conditions are favorable, the spore mother cell initiates meiosis, reducing the chromosome number by half to produce haploid spores. These spores are lightweight and easily dispersed, a strategy particularly advantageous for plants like mosses and fungi. The haploid phase, represented by the gametophyte, is shorter and dedicated to reproduction. For instance, in liverworts, the gametophyte produces gametes that, upon fertilization, restore the diploid state, completing the cycle.

From a practical standpoint, recognizing these phases is vital for fields like agriculture and conservation. For example, in crop plants that exhibit alternation of generations, such as certain algae used in aquaculture, understanding the diploid and haploid stages can optimize growth and yield. Farmers can manipulate environmental conditions to favor the diploid sporophyte phase for biomass production or the haploid gametophyte phase for seed development. Similarly, in conservation efforts for endangered ferns or mosses, knowing when and how spore mother cells transition between phases can enhance propagation success.

A comparative analysis reveals that the diploid phase often dominates in terms of size and longevity, while the haploid phase is more agile and reproductive. This division of labor ensures that organisms can both endure and adapt. For instance, the diploid sporophyte in pines is a towering, long-lived structure, whereas the haploid gametophyte is microscopic and short-lived but crucial for genetic recombination. This contrast highlights the evolutionary elegance of alternating life cycles, where each phase complements the other to maximize fitness.

In conclusion, the diploid and haploid phases in organisms with spore mother cells are not just distinct stages but interdependent partners in a complex life cycle. The spore mother cell, being diploid, serves as the bridge between these phases, ensuring continuity and diversity. By studying these transitions, we gain insights into the resilience of life and practical tools for managing ecosystems and crops. Whether in a laboratory or a forest, this knowledge underscores the importance of every stage in the cycle of life.

Mastering Spore: Tips to Create a Perfectly Upright Creature

You may want to see also

Exceptions in Plant Life Cycles: Identify cases where spore mother cells deviate from typical diploid status

In the realm of plant biology, the spore mother cell (SMC) is typically diploid, undergoing meiosis to produce haploid spores. However, certain plant species defy this norm, exhibiting deviations in ploidy levels that challenge conventional understanding. One notable example is found in some ferns, where the SMC can be polyploid, containing multiple sets of chromosomes. This anomaly arises from endoreduplication, a process in which the genome is replicated without cell division, resulting in cells with ploidy levels greater than diploid. For instance, the SMC in the fern *Marsilea vestita* has been reported to be tetraploid, highlighting the diversity in ploidy status among plant species.

Consider the life cycle of certain bryophytes, such as liverworts, where the SMC may exhibit haploid or diploid states depending on the species and environmental conditions. In *Marchantia polymorpha*, a model liverwort, the SMC is haploid during the gametophytic phase, contrasting sharply with the typical diploid expectation. This deviation is attributed to the alternation of generations, where the gametophyte dominates the life cycle, and the sporophyte is nutritionally dependent on it. Understanding these exceptions requires a nuanced approach, as they often involve complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and developmental factors.

To identify these exceptions, researchers employ cytological techniques such as chromosome counting and flow cytometry. For example, in a study on the ploidy of SMCs in *Selaginella*, a primitive vascular plant, researchers used Feulgen DNA cytophotometry to confirm that the SMC is indeed diploid, despite the plant’s unique heterospory. However, in *Isoetes*, another heterosporous plant, the SMC has been observed to be polyploid in some species, underscoring the importance of species-specific analysis. Practical tips for researchers include using fresh plant material for accurate cytological observations and employing multiple techniques to validate ploidy levels.

A comparative analysis of these exceptions reveals that deviations in SMC ploidy are often linked to evolutionary adaptations. Polyploidy in SMCs, for instance, can enhance genetic diversity and adaptability, particularly in environments with fluctuating conditions. In *Spartina*, a genus of grasses, polyploid SMCs contribute to the species' ability to colonize diverse habitats, including saline marshes. Conversely, haploid SMCs in certain bryophytes may reflect an ancestral condition, providing insights into the evolutionary trajectory of land plants. This comparative perspective highlights the functional significance of ploidy deviations in plant life cycles.

In conclusion, exceptions to the typical diploid status of SMCs in plant life cycles are not merely anomalies but windows into the evolutionary and developmental plasticity of plants. From polyploid SMCs in ferns to haploid SMCs in liverworts, these deviations underscore the diversity of plant reproductive strategies. For botanists and plant biologists, recognizing and studying these exceptions is crucial for understanding the mechanisms driving plant evolution and adaptation. By integrating cytological techniques and comparative analyses, researchers can unravel the complexities of these deviations, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of plant biology.

Mastering EvoAdvantage in Spore: Tips for Evolution Success

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the spore mother cell is diploid, meaning it contains two sets of chromosomes.

The spore mother cell undergoes meiosis, a type of cell division that reduces the chromosome number by half, to form haploid spores.

The spore mother cell is found in plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) and fungi, where it plays a role in the production of spores for reproduction and dispersal.

The spores produced by the spore mother cell are haploid, as they result from meiosis, which reduces the chromosome number from diploid to haploid.