Fungal spores are microscopic, reproductive structures produced by fungi to propagate and survive in diverse environments. They are characterized by their lightweight, resilient nature, allowing them to disperse easily through air, water, or animals. Key features include a protective cell wall composed of chitin, which provides durability against harsh conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and UV radiation. Spores are highly diverse in shape, size, and color, reflecting the wide variety of fungal species. They are metabolically dormant, enabling long-term survival until favorable conditions trigger germination. Additionally, fungal spores often possess specialized structures, such as appendages or melanin pigments, that enhance their dispersal and resistance. These characteristics make spores essential for fungal survival, colonization, and ecological roles, including decomposition and symbiotic relationships.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Size | Typically 1-100 μm in diameter, depending on the species |

| Shape | Diverse shapes, including spherical, oval, cylindrical, or filamentous |

| Wall Composition | Primarily composed of chitin, glucans, and other polysaccharides, providing structural support and protection |

| Pigmentation | May be colorless, or exhibit various pigments (e.g., melanin) for UV protection and environmental adaptation |

| Reproduction | Asexual (e.g., conidia, spores) or sexual (e.g., asci, basidiospores) |

| Dispersal | Dispersed through air, water, or vectors (e.g., insects, animals) |

| Dormancy | Can remain dormant for extended periods under unfavorable conditions |

| Germination | Requires specific environmental triggers (e.g., moisture, temperature, nutrients) to initiate growth |

| Resistance | Highly resistant to desiccation, extreme temperatures, and UV radiation |

| Metabolism | Generally inactive until germination, relying on stored nutrients |

| Genetic Material | Contains haploid or diploid genetic material, depending on the life cycle stage |

| Ecological Role | Play crucial roles in ecosystems as decomposers, pathogens, or symbionts |

| Antigenicity | Can elicit immune responses in humans and animals, leading to allergies or infections |

| Longevity | Can survive for years in the environment, depending on conditions |

| Surface Features | May have surface structures (e.g., spines, warts) aiding in dispersal or attachment |

What You'll Learn

- Size and Shape: Spores vary in size, shape, and structure, aiding in identification and dispersal methods

- Wall Composition: Cell walls contain chitin, providing rigidity and protection against environmental stresses

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores use wind, water, animals, or explosive release for efficient dissemination

- Dormancy and Survival: Spores can remain dormant for years, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments

- Germination Triggers: Specific factors like moisture, temperature, and nutrients activate spore germination

Size and Shape: Spores vary in size, shape, and structure, aiding in identification and dispersal methods

Fungal spores exhibit a remarkable diversity in size, typically ranging from 1 to 100 micrometers in diameter. This variation is not arbitrary; it directly influences their dispersal methods. Smaller spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* (2–5 μm), are lightweight and easily carried by air currents, facilitating long-distance travel. Larger spores, like those of *Coprinus* (10–20 μm), often rely on water or animals for dispersal due to their greater mass. Understanding these size differences is crucial for predicting fungal spread in environments, from agricultural fields to indoor spaces.

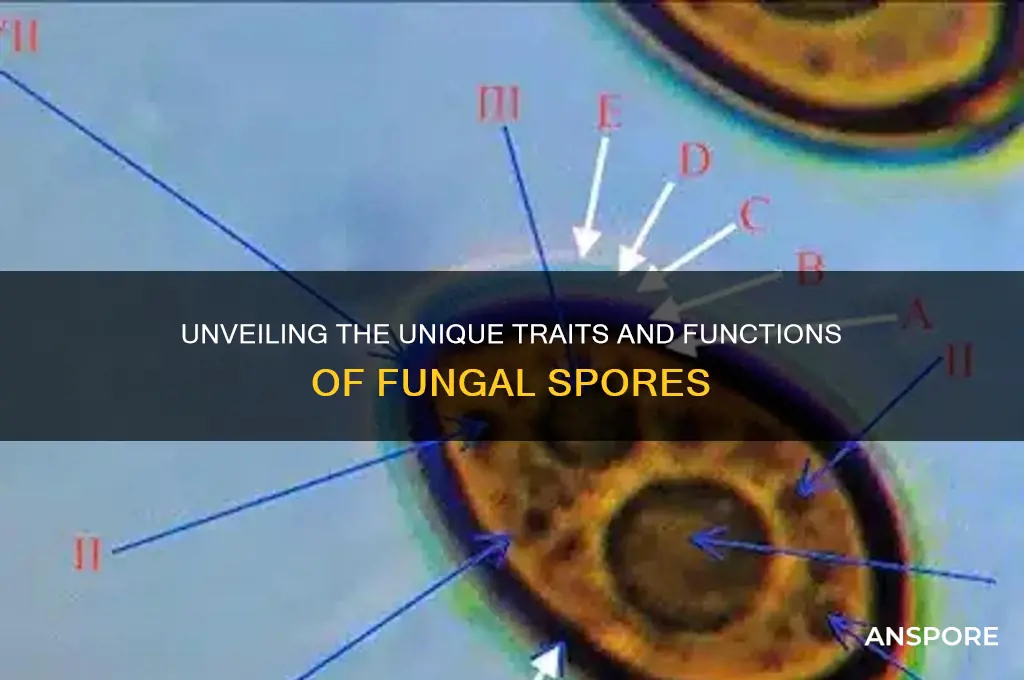

Shape plays an equally vital role in spore function and identification. Spherical spores, common in *Cryptococcus*, maximize surface area for adhesion, aiding in colonization of surfaces. Elongated or cylindrical spores, as seen in *Fusarium*, reduce water retention, making them more resistant to rain impact and suitable for wind dispersal. Some spores, like those of *Penicillium*, have unique shapes (e.g., flask-like) that enhance their ability to attach to surfaces or resist environmental stresses. These morphological adaptations highlight the evolutionary precision of fungal spores.

Structural features further differentiate spores and support their ecological roles. For instance, spores with thick walls, such as those of *Cladosporium*, are more resistant to desiccation and UV radiation, enabling survival in harsh conditions. In contrast, thin-walled spores, like those of *Alternaria*, prioritize rapid germination in favorable environments. Surface textures, such as spines or ridges, as seen in *Trichoderma*, reduce clumping and improve aerodynamic properties, aiding in wind dispersal. These structural variations are key diagnostic traits for mycologists identifying fungal species.

Practical applications of spore size and shape are evident in fields like agriculture and medicine. Farmers monitor spore dimensions to predict disease outbreaks, as smaller spores of pathogens like *Puccinia* (rust fungi) can travel farther and infect crops more rapidly. In allergology, spore shape helps differentiate allergens; for example, the round spores of *Alternaria* are more likely to trigger respiratory reactions than irregularly shaped ones. By studying these characteristics, professionals can develop targeted strategies for control and prevention.

In summary, the size, shape, and structure of fungal spores are not merely descriptive traits but functional adaptations that dictate their dispersal and survival. From the microscopic precision of their dimensions to the intricate details of their morphology, these features offer a wealth of information for identification and ecological understanding. Whether in research, agriculture, or health, recognizing these variations empowers us to manage fungal interactions more effectively.

Preventing Spores from Germinating in Food: Effective Strategies for Safety

You may want to see also

Wall Composition: Cell walls contain chitin, providing rigidity and protection against environmental stresses

Fungal spores are marvels of nature, designed to withstand harsh conditions while remaining lightweight and dispersible. Central to their resilience is the composition of their cell walls, which contain chitin—a polysaccharide also found in the exoskeletons of arthropods. This unique material provides fungal spores with the structural integrity needed to endure environmental stresses, from desiccation to extreme temperatures. Unlike plant cell walls, which rely on cellulose, chitin offers a distinct advantage: it combines flexibility with strength, allowing spores to remain intact yet adaptable in diverse habitats.

Consider the practical implications of chitin in spore walls. For instance, in agricultural settings, understanding this composition can inform strategies for fungal control. Chitin-degrading enzymes, such as chitinases, are already used in biocontrol agents to disrupt fungal pathogens. Gardeners and farmers can leverage this knowledge by applying chitinase-based products to target unwanted fungi without harming beneficial microorganisms. Additionally, researchers are exploring chitin’s role in spore longevity, which could lead to innovations in food preservation or pharmaceutical storage by mimicking spore resilience.

From a comparative perspective, chitin sets fungal spores apart from bacterial endospores, which rely on layers of peptidoglycan and dipicolinic acid for durability. While both structures are highly resistant, chitin’s presence in fungal spores enables them to maintain a balance between protection and metabolic dormancy. This distinction is critical in medical and industrial applications. For example, antifungal treatments often target chitin synthesis, as seen in drugs like nikkomycin, which inhibit fungal growth by disrupting cell wall formation. Understanding this mechanism can guide more precise therapeutic interventions.

Descriptively, chitin in spore walls acts as a molecular shield, a barrier that repels water and resists enzymatic degradation. Imagine a microscopic fortress, its walls reinforced with a material that neither cracks under pressure nor dissolves in rain. This protective layer ensures spores can survive in soil, air, and even animal hosts for years, waiting for optimal conditions to germinate. For hobbyists cultivating mushrooms or studying mycology, recognizing chitin’s role underscores the importance of maintaining stable humidity and temperature to trigger spore activation effectively.

In conclusion, the presence of chitin in fungal spore cell walls is a key to their survival and adaptability. Whether you’re a researcher, farmer, or enthusiast, appreciating this structural feature unlocks practical insights into managing, studying, or harnessing fungal spores. From biocontrol to biotechnology, chitin’s role in spore resilience is a testament to nature’s ingenuity—and a reminder of the untapped potential within these microscopic powerhouses.

Using Milky Spore Granules in Flower Beds: Safe and Effective?

You may want to see also

Dispersal Mechanisms: Spores use wind, water, animals, or explosive release for efficient dissemination

Fungal spores are nature's master dispersers, employing a variety of mechanisms to ensure their survival and propagation. Among these, wind dispersal stands out as the most common method. Spores, often lightweight and equipped with structures like wings or air pockets, are easily carried over vast distances by air currents. For instance, the asexual spores of *Aspergillus* fungi, measuring just 3-5 micrometers in diameter, can travel hundreds of miles, colonizing new environments with remarkable efficiency. This passive yet effective strategy highlights the adaptability of fungi to exploit natural forces for dissemination.

While wind is a dominant player, water serves as another critical medium for spore dispersal, particularly in aquatic and semi-aquatic environments. Fungal spores like those of *Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis*, the chytrid fungus responsible for amphibian declines, thrive in moist conditions and are readily transported via water flow. Rain splash, a localized yet powerful mechanism, dislodges spores from fungal structures and propels them onto nearby surfaces, ensuring colonization of adjacent areas. This method is especially effective in dense ecosystems like rainforests, where water acts as both a carrier and a catalyst for spore germination.

Animals, too, play an underappreciated role in fungal spore dispersal. Spores can adhere to the fur, feathers, or skin of animals, hitching a ride to new locations. For example, the spores of *Puccinia* rust fungi, which infect plants, are often spread by insects or grazing mammals. Some fungi, like those in the genus *Elaphomyces*, produce spore-filled truffles that are consumed by mammals and birds, with spores passing through the digestive tract unharmed and deposited in new habitats. This symbiotic relationship underscores the ingenuity of fungi in leveraging animal behavior for their dispersal needs.

Perhaps the most dramatic dispersal mechanism is the explosive release of spores, a strategy employed by certain fungi to maximize distance and efficiency. The "puffball" fungi, such as *Lycoperdon*, develop internal pressure within their fruiting bodies, which, when triggered, release a cloud of spores into the air. This method can propel spores several feet, significantly increasing their chances of encountering favorable conditions for growth. Similarly, the "gunpowder fungus" (*Poria* species) ejects spores with such force that they can be heard as a faint popping sound. These explosive mechanisms demonstrate the evolutionary sophistication of fungi in overcoming dispersal challenges.

Understanding these dispersal mechanisms is not just an academic exercise—it has practical implications for agriculture, medicine, and conservation. For instance, knowing that wind-dispersed spores can travel long distances helps farmers implement quarantine measures to prevent the spread of crop diseases. Similarly, awareness of water-borne spore transmission informs strategies to mitigate chytridiomycosis in amphibian populations. By studying these mechanisms, we gain insights into fungal ecology and develop targeted interventions to manage both beneficial and harmful fungi effectively.

Understanding Bliss Spore Lifespan: Duration, Storage, and Freshness Tips

You may want to see also

Dormancy and Survival: Spores can remain dormant for years, surviving harsh conditions until favorable environments

Fungal spores are masters of endurance, capable of entering a state of dormancy that allows them to withstand extreme conditions—from scorching heat to freezing temperatures, desiccation, and even exposure to radiation. This remarkable ability ensures their survival across time and space, often remaining viable for decades or even centuries. For instance, spores of the fungus *Cladosporium sphaerospermum* have been found dormant in Antarctic ice cores, only to revive when conditions became favorable. This resilience is not just a biological curiosity; it’s a survival strategy that enables fungi to colonize diverse ecosystems, from arid deserts to nutrient-poor soils.

To achieve such longevity, spores employ a suite of protective mechanisms. Their cell walls are often thickened and enriched with melanin, a pigment that shields them from UV radiation and oxidative stress. Additionally, spores reduce their metabolic activity to near-zero levels, minimizing energy consumption and preserving internal resources. This state of suspended animation is further supported by the accumulation of protective compounds like trehalose, a sugar that stabilizes cellular structures during dehydration. These adaptations collectively ensure that spores can endure environments that would be lethal to most other life forms.

Understanding spore dormancy has practical implications, particularly in fields like agriculture and food preservation. For example, dormant fungal spores can contaminate stored grains, only to germinate when moisture levels rise, leading to crop spoilage. To mitigate this, farmers and food processors use techniques such as heat treatment (above 60°C for 30 minutes) or controlled atmospheres (low oxygen, high carbon dioxide) to eliminate dormant spores. Similarly, in medical settings, recognizing the resilience of fungal spores is crucial for sterilizing surgical instruments and preventing hospital-acquired infections.

Comparatively, the dormancy of fungal spores shares similarities with bacterial endospores but differs in key ways. While both are highly resistant structures, fungal spores retain their cellular organization and can germinate directly into hyphae, whereas bacterial endospores must first rehydrate and reform a vegetative cell. This distinction highlights the unique evolutionary strategies fungi have developed to survive adversity. By studying these mechanisms, scientists can develop more effective antifungal agents and preservation methods, leveraging nature’s own designs to combat spoilage and disease.

In conclusion, the dormancy and survival capabilities of fungal spores are a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity. From their protective cell walls to their metabolic shutdown, every aspect of their design is optimized for endurance. Whether in the lab, the field, or the kitchen, understanding these traits empowers us to control fungal growth where it’s unwanted and harness it where it’s beneficial. Practical tips, such as maintaining low humidity in storage areas or using fungicides strategically, can help manage spore-related challenges effectively. By respecting the resilience of these microscopic survivors, we can better navigate the fungal world around us.

Does Serratia Marcescens Form Spores? Unraveling the Bacterial Mystery

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: Specific factors like moisture, temperature, and nutrients activate spore germination

Fungal spores, akin to seeds in the plant world, remain dormant until specific environmental cues awaken them. These germination triggers—moisture, temperature, and nutrients—act as a biological alarm clock, signaling the spore to sprout and establish a new fungal colony. Understanding these triggers is crucial for both harnessing fungi’s benefits, such as in agriculture or biotechnology, and controlling their spread in unwanted contexts, like food spoilage or infections.

Moisture: The Universal Catalyst

Water is the most critical factor for spore germination, acting as both a solvent and a medium for nutrient uptake. Spores absorb moisture through their cell walls, rehydrating internal structures and activating metabolic processes. For example, *Aspergillus* spores require a water activity (aw) of at least 0.78 to germinate, while *Penicillium* can activate at aw levels as low as 0.81. Practical tip: To prevent fungal growth in stored grains, maintain relative humidity below 60%, reducing available moisture for spores. Conversely, in mushroom cultivation, misting substrates with water to achieve 90–95% humidity ensures optimal germination.

Temperature: The Goldilocks Zone

Temperature acts as a fine-tuned regulator, with each fungal species having a specific range where germination thrives. Mesophilic fungi, like *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*, germinate best between 20–30°C, while thermophilic species, such as *Chaetomium*, require temperatures above 45°C. Cold-tolerant fungi, like *Geomyces*, can germinate at temperatures as low as 4°C. Caution: Sudden temperature fluctuations can inhibit germination or trigger dormancy mechanisms. For instance, chilling spores of *Fusarium* below 10°C halts germination, a tactic used in seed treatment to suppress soil-borne pathogens.

Nutrients: Fuel for Growth

Spores are metabolically inactive and rely on external nutrients to initiate germination. Simple sugars like glucose or fructose are preferred energy sources, while nitrogen compounds such as ammonium or amino acids are essential for protein synthesis. For example, *Neurospora crassa* spores require a carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of 10:1 for efficient germination. In practical applications, enriching growth media with 2% glucose and 0.5% yeast extract accelerates spore germination in laboratory cultures. Conversely, nutrient deprivation can prolong dormancy, a strategy used in food preservation to inhibit mold growth.

Synergy of Triggers: A Holistic Approach

While each trigger plays a distinct role, their combined effect is often synergistic. For instance, moisture and temperature work in tandem: at 25°C and 90% humidity, *Botrytis cinerea* spores germinate within 6 hours, but at 15°C, germination delays by 48 hours despite adequate moisture. Nutrients amplify this effect; adding 1% peptone to a moist substrate at 28°C reduces *Trichoderma* germination time from 12 to 4 hours. Takeaway: Controlling these factors collectively is key to managing fungal spores, whether fostering growth in biotechnological processes or suppressing it in clinical or agricultural settings.

By manipulating moisture, temperature, and nutrients, one can precisely control spore germination, turning these microscopic entities into allies or adversaries based on need. This knowledge bridges the gap between theoretical biology and practical application, offering actionable strategies for diverse fields.

Mastering Spore Galactic Adventures: Seamless Save Transfer Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungal spores are typically lightweight, microscopic, and highly resistant to environmental stresses. They are designed for dispersal and survival, often possessing thick cell walls that protect them from desiccation, UV radiation, and other harsh conditions.

Fungal spores exhibit a wide range of shapes and sizes depending on the species. They can be round, oval, cylindrical, or elongated, and their size varies from a few micrometers to several tens of micrometers. For example, yeast spores are generally smaller, while mold spores can be larger and more complex.

Pigmentation in fungal spores often serves as a protective mechanism against UV radiation and other environmental factors. Colors can range from white and cream to green, brown, or black, depending on the species. Pigments may also play a role in spore maturation and dispersal.