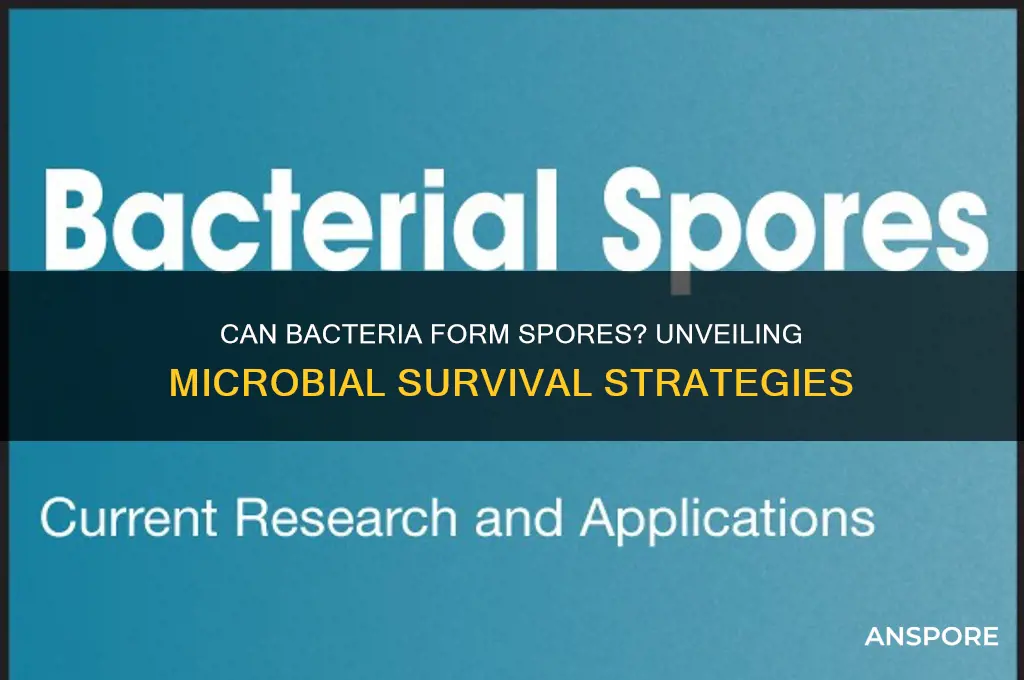

Bacteria, known for their remarkable adaptability, have evolved various survival strategies to endure harsh environmental conditions. One such strategy is the formation of spores, a dormant and highly resistant cell type that allows certain bacterial species to withstand extreme temperatures, desiccation, and exposure to chemicals. This process, known as sporulation, is primarily observed in specific genera like *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*. Spores can remain viable for extended periods, sometimes even centuries, and germinate into active bacteria when conditions become favorable again. Understanding bacterial sporulation is crucial, as it has significant implications in fields such as food safety, medicine, and environmental science, where spore-forming bacteria can pose challenges due to their resilience.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ability to Form Spores | Some bacteria, primarily Gram-positive species, can form spores (endospores) as a survival mechanism. |

| Type of Bacteria | Primarily found in the phylum Firmicutes, including genera like Bacillus, Clostridium, and Sporosarcina. |

| Purpose of Spores | Spores are highly resistant structures that allow bacteria to survive extreme conditions such as heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemicals. |

| Location of Spore Formation | Spores are formed within the bacterial cell (endospore) and are typically located centrally or at one end of the cell. |

| Structure of Spores | Spores consist of a core containing DNA, ribosomes, and enzymes, surrounded by multiple protective layers: the spore coat, cortex, and sometimes an exosporium. |

| Resistance Capabilities | Spores can remain viable for years or even decades in harsh environments, making them highly resilient. |

| Germination Process | Under favorable conditions, spores can germinate, reverting to the vegetative (active) form of the bacterium. |

| Examples of Spore-Forming Bacteria | Bacillus anthracis (causes anthrax), Clostridium botulinum (causes botulism), Bacillus cereus (food poisoning). |

| Medical and Industrial Significance | Spores pose challenges in sterilization processes and are relevant in food safety, healthcare, and biotechnology. |

| Detection Methods | Spores can be detected using heat resistance tests, staining techniques (e.g., Schaeffer-Fulton stain), and molecular methods. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Sporulation Process: How and why bacteria form spores under stress conditions

- Types of Spores: Endospores vs. exospores: differences in structure and function

- Survival Mechanisms: Spores' resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals for long-term survival

- Germination Triggers: Conditions required for spores to return to active bacterial growth

- Medical Significance: Role of bacterial spores in infections and disease transmission

Sporulation Process: How and why bacteria form spores under stress conditions

Bacteria, when faced with adverse environmental conditions such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperatures, or desiccation, can undergo a remarkable transformation known as sporulation. This process results in the formation of highly resistant endospores, which allow the bacteria to survive in a dormant state for extended periods. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can withstand harsh conditions like UV radiation, chemicals, and even the vacuum of space. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* and *Clostridium botulinum* are well-known spore-forming bacteria, with the latter being a significant concern in food preservation due to its ability to cause botulism.

The sporulation process is a complex, multi-step cellular program triggered by stress signals. It begins with the activation of specific genes in response to environmental cues, such as the depletion of carbon or nitrogen sources. The bacterium then undergoes asymmetric cell division, forming a smaller forespore within the larger mother cell. This forespore is engulfed by the mother cell, which then synthesizes a protective coat composed of proteins, peptidoglycan, and other layers. The mature spore is eventually released when the mother cell lyses, leaving behind a structure capable of surviving extreme conditions. This intricate process is energetically costly, yet it ensures the bacterium’s long-term survival.

From a practical standpoint, understanding sporulation is crucial for industries like food safety and medicine. For example, spores of *Clostridium perfringens* can survive cooking temperatures and cause foodborne illness if not eliminated through proper sterilization techniques, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–30 minutes. Similarly, in healthcare, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus anthracis* (the causative agent of anthrax) pose a bioterrorism threat due to their resilience. Effective decontamination strategies, such as the use of hydrogen peroxide vapor or formaldehyde, target spore structures to ensure complete eradication.

Comparatively, sporulation is not a universal bacterial trait but is limited to specific genera, primarily within the Firmicutes phylum. This distinction highlights the evolutionary advantage of sporulation in niche environments where survival depends on enduring prolonged stress. For instance, spores of *Bacillus* species have been found in ancient sediments, demonstrating their ability to persist for thousands of years. In contrast, non-spore-forming bacteria like *Escherichia coli* rely on other mechanisms, such as biofilm formation, to cope with stress, but these are less effective in extreme conditions.

In conclusion, the sporulation process is a fascinating adaptation that showcases bacterial resilience in the face of adversity. By forming spores, bacteria ensure their genetic continuity even when vegetative growth is impossible. This mechanism has profound implications for both natural ecosystems and human activities, from food preservation to medical sterilization. Understanding the how and why of sporulation not only deepens our appreciation of microbial life but also equips us with the knowledge to combat spore-related challenges effectively.

Understanding the Meaning and Usage of 'Spor' in Language and Culture

You may want to see also

Types of Spores: Endospores vs. exospores: differences in structure and function

Bacteria have evolved remarkable strategies to survive harsh conditions, and spore formation is one of their most fascinating adaptations. Among bacterial spores, endospores and exospores stand out, yet they differ fundamentally in structure, formation, and function. Understanding these differences is crucial for fields like microbiology, medicine, and environmental science.

Endospores, primarily formed by Gram-positive bacteria such as *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are highly resistant structures produced within the bacterial cell. Structurally, they consist of a core containing DNA, ribosomes, and enzymes, surrounded by a thick, multi-layered coat. This coat includes a cortex rich in peptidoglycan and a proteinaceous outer layer, making endospores resistant to heat, radiation, desiccation, and chemicals. For instance, *Bacillus anthracis* endospores can survive in soil for decades, posing a bioterrorism threat. Functionally, endospores are dormant forms that halt metabolic activity, allowing bacteria to endure extreme environments until conditions improve. Their resistance is so profound that autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes is required to sterilize them, a standard in laboratory and medical settings.

In contrast, exospores are less common and structurally simpler. Formed externally to the bacterial cell, they are typically observed in some Gram-negative bacteria like *Azotobacter*. Exospores lack the complex layers of endospores, consisting mainly of a protective outer membrane and cytoplasmic contents. This simplicity makes them less resistant to environmental stresses compared to endospores. Exospores are often associated with desiccation tolerance in soil bacteria, enabling survival in arid conditions. However, they are more vulnerable to heat and chemicals, typically inactivated at temperatures above 80°C. Their formation is a rapid response to environmental stress, unlike the energy-intensive process of endospore formation.

The functional differences between these spores reflect their ecological roles. Endospores are a long-term survival mechanism, ensuring bacterial persistence in unpredictable environments. Exospores, on the other hand, are a short-term adaptation, allowing bacteria to withstand temporary stresses like drought. For practical applications, understanding these differences is vital. For example, in food preservation, knowing that exospores are less heat-resistant than endospores helps in designing effective pasteurization processes. Similarly, in healthcare, recognizing the extreme resilience of endospores informs sterilization protocols for surgical instruments.

In summary, while both endospores and exospores are bacterial survival strategies, their structural complexity and resistance levels diverge significantly. Endospores are the ultimate survivalists, withstanding extreme conditions through their multi-layered armor, whereas exospores offer a quicker, less robust solution. By distinguishing between these spore types, scientists and practitioners can tailor strategies to control or utilize bacteria in various contexts, from environmental remediation to medical sterilization.

Can You See Mold Spores? Unveiling the Invisible Threat in Your Home

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: Spores' resistance to heat, radiation, and chemicals for long-term survival

Bacteria, when faced with harsh environmental conditions, employ a remarkable survival strategy: the formation of spores. These dormant structures are not just a passive response to stress but a highly evolved mechanism that ensures long-term survival. Among their most impressive traits is their resistance to extreme conditions, including heat, radiation, and chemicals, which would otherwise be lethal to the vegetative form of the bacterium. This resilience is not merely a biological curiosity; it has profound implications for fields ranging from food safety to space exploration.

Consider the heat resistance of bacterial spores, particularly those of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium* species. These spores can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C, far beyond what most life forms can tolerate. For instance, boiling water (100°C) is insufficient to destroy spores of *Clostridium botulinum*, the causative agent of botulism. To ensure safety, food preservation methods like canning require temperatures of 121°C for at least 3 minutes, achieved through autoclaving. This process, known as sterilization, is a direct response to the spore’s ability to endure heat, demonstrating how their resistance shapes practical applications in industry and healthcare.

Radiation resistance is another critical survival mechanism of spores. Unlike vegetative cells, spores can repair DNA damage caused by ionizing radiation, such as UV light or gamma rays. This is due to their thick, multi-layered coat and the presence of small, acid-soluble proteins (SASPs) that protect DNA. For example, spores of *Deinococcus radiodurans* can survive doses of radiation up to 5,000 grays (Gy), compared to a lethal dose of 5 Gy for humans. This extraordinary resistance has led to their study in astrobiology, where understanding spore survival in space radiation is crucial for assessing the potential for life beyond Earth.

Chemical resistance further underscores the spore’s adaptability. Spores are impervious to many disinfectants, including ethanol and quaternary ammonium compounds, commonly used in household cleaners. This resistance is attributed to their outer exosporium layer, which acts as a barrier against chemical penetration. In practical terms, this means that standard cleaning agents may not be effective against spore-forming bacteria, necessitating the use of specialized sporicides like hydrogen peroxide or bleach. For instance, a 10% bleach solution (5,000 ppm chlorine) is recommended for surfaces contaminated with *Clostridioides difficile* spores, a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections.

The implications of spore resistance extend beyond microbiology, influencing industries and daily life. In food production, understanding spore survival is critical for preventing contamination and spoilage. In healthcare, it informs sterilization protocols for medical equipment. Even in space exploration, spore resistance to radiation and extreme conditions raises questions about the potential for life to travel between planets, a concept known as panspermia. By studying these mechanisms, we not only gain insight into bacterial survival but also develop strategies to combat pathogens and harness their resilience for technological advancements.

The Last of Us: Unveiling the Truth About Spores in the Show

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$430.79 $589.95

Germination Triggers: Conditions required for spores to return to active bacterial growth

Bacterial spores are remarkable survival structures, capable of enduring extreme conditions that would destroy their vegetative counterparts. However, these dormant forms do not remain inactive indefinitely. Germination—the process by which spores revert to active bacterial growth—is triggered by specific environmental cues. Understanding these triggers is crucial for fields like food safety, medicine, and environmental science, as they dictate when and where bacteria can re-emerge as a threat or a benefit.

Analytical Perspective:

Spores require a combination of nutrient availability and optimal environmental conditions to initiate germination. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* spores respond to amino acids like L-valine, often at concentrations as low as 1–10 mM, which act as chemical signals to exit dormancy. Similarly, *Clostridium botulinum* spores, notorious for causing botulism, germinate in the presence of specific sugars and amino acids found in food products. Temperature also plays a critical role; most bacterial spores germinate efficiently between 25°C and 37°C, though some thermophilic species require higher temperatures. pH levels typically need to be neutral to slightly alkaline, as acidic conditions can inhibit germination. These precise requirements ensure spores remain dormant until conditions are favorable for growth, maximizing their survival strategy.

Instructive Approach:

To induce spore germination in a laboratory setting, follow these steps: First, prepare a nutrient-rich medium containing germinants like L-alanine, inositol, or glucose, depending on the bacterial species. For example, *Bacillus cereus* spores often require a combination of L-alanine and inositol. Second, adjust the medium’s pH to 7.0–7.5 and incubate at 37°C. Monitor the culture for signs of active growth, such as increased turbidity or colony formation on agar plates. Caution: Avoid using excessive germinant concentrations, as this can lead to incomplete germination or cell damage. For food safety applications, ensure that processing temperatures exceed 121°C for at least 15 minutes to destroy spores in canned goods, as many spores can survive milder heat treatments.

Comparative Insight:

Unlike vegetative bacteria, which grow and divide under a wide range of conditions, spores are highly selective about their reactivation triggers. For example, while *Bacillus anthracis* spores germinate readily in the presence of blood or tissue fluids, *Clostridium sporogenes* spores require specific sugars like mannose. This specificity reflects their ecological niches; *B. anthracis* thrives in mammalian hosts, while *C. sporogenes* is often found in soil. In contrast, some spores, like those of *Geobacillus stearothermophilus*, require temperatures above 50°C to germinate, a trait adapted to their thermophilic habitats. These differences highlight the evolutionary fine-tuning of germination triggers to ensure survival in diverse environments.

Descriptive Narrative:

Imagine a spore resting in soil, encased in a protective coat, biding its time. When rain introduces nutrients into the soil, the spore detects a surge in amino acids and sugars. Its internal mechanisms spring into action: the spore’s cortex swells as it absorbs water, and enzymes begin to degrade the protective coat. Within minutes to hours, the spore sheds its dormant state, emerging as a metabolically active bacterium ready to colonize its environment. This transformation is not just a biological process but a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life, even in its most dormant forms.

Practical Takeaway:

For industries dealing with spore-forming bacteria, controlling germination triggers is key to prevention. In food processing, avoid combining heat-treated products with ingredients that could introduce germinants, such as raw sugars or amino acid-rich additives. In healthcare, sterilize medical equipment at temperatures exceeding 132°C to ensure spore destruction. For environmental applications, monitor nutrient levels in soil and water to predict potential bacterial outbreaks. By understanding and manipulating these triggers, we can mitigate risks and harness the benefits of bacterial spores in biotechnology and beyond.

Heat's Role in Spore Staining: Enhancing Accuracy and Visualization

You may want to see also

Medical Significance: Role of bacterial spores in infections and disease transmission

Bacterial spores are a double-edged sword in medicine. While their dormant, resilient nature allows them to survive extreme conditions, it also makes them formidable adversaries in infection control. Unlike actively replicating bacteria, spores can withstand boiling temperatures, desiccation, and many disinfectants, lurking in hospital environments for years. This tenacity poses a significant challenge in healthcare settings, where spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* and *Bacillus anthracis* can cause severe, often life-threatening infections.

Understanding the role of bacterial spores in disease transmission is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Consider *C. difficile*, a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis, particularly in hospitalized patients. This bacterium forms spores that persist on surfaces long after the vegetative cells have been eliminated. When ingested, these spores can germinate in the gut, leading to toxin production and severe gastrointestinal symptoms. The risk is highest among elderly patients, those with compromised immune systems, and individuals on prolonged antibiotic therapy, which disrupts the gut microbiome and allows *C. difficile* to flourish. Preventing *C. difficile* transmission requires meticulous hand hygiene, contact precautions, and thorough environmental disinfection with spore-killing agents like chlorine bleach.

Healthcare professionals must be vigilant in identifying high-risk patients and implementing targeted infection control measures.

The threat extends beyond healthcare settings. *Bacillus anthracis*, the causative agent of anthrax, forms highly resilient spores that can remain viable in soil for decades. Inhalation of these spores can lead to a rapidly progressing and often fatal pulmonary infection. While naturally occurring anthrax is rare, its potential use as a bioterrorism agent underscores the importance of preparedness. Vaccination against anthrax is available for high-risk individuals, such as military personnel and laboratory workers. In the event of exposure, prompt administration of antibiotics like ciprofloxacin or doxycycline, combined with antitoxin therapy, is crucial for survival.

The medical significance of bacterial spores lies not only in their ability to cause disease but also in their potential as therapeutic tools. Spores of certain *Bacillus* species, for example, are being investigated as vehicles for targeted drug delivery and cancer therapy. Their ability to germinate in specific microenvironments, such as tumors, offers a unique opportunity for precise treatment. However, harnessing this potential requires a deep understanding of spore biology and careful consideration of safety concerns.

Understanding Bacterial Spores: Formation, Function, and Survival Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, not all bacteria can form spores. Only certain types of bacteria, such as those in the genera *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, have the ability to form spores as a survival mechanism.

Bacteria form spores to survive harsh environmental conditions, such as extreme temperatures, lack of nutrients, or exposure to chemicals, that would otherwise kill them in their vegetative state.

Some bacterial spores, like those of *Clostridium botulinum* or *Bacillus anthracis*, can cause serious diseases if they germinate and multiply in the body. However, spores themselves are generally not harmful until they return to their active, vegetative form.

Bacterial spores are highly resilient and can survive for years, even decades, in unfavorable conditions. Their durability makes them difficult to eradicate without extreme measures like high heat or strong chemicals.

Regular cleaning methods are often ineffective against bacterial spores. Specialized techniques, such as autoclaving (high-pressure steam sterilization) or treatment with strong disinfectants like bleach, are typically required to destroy them.