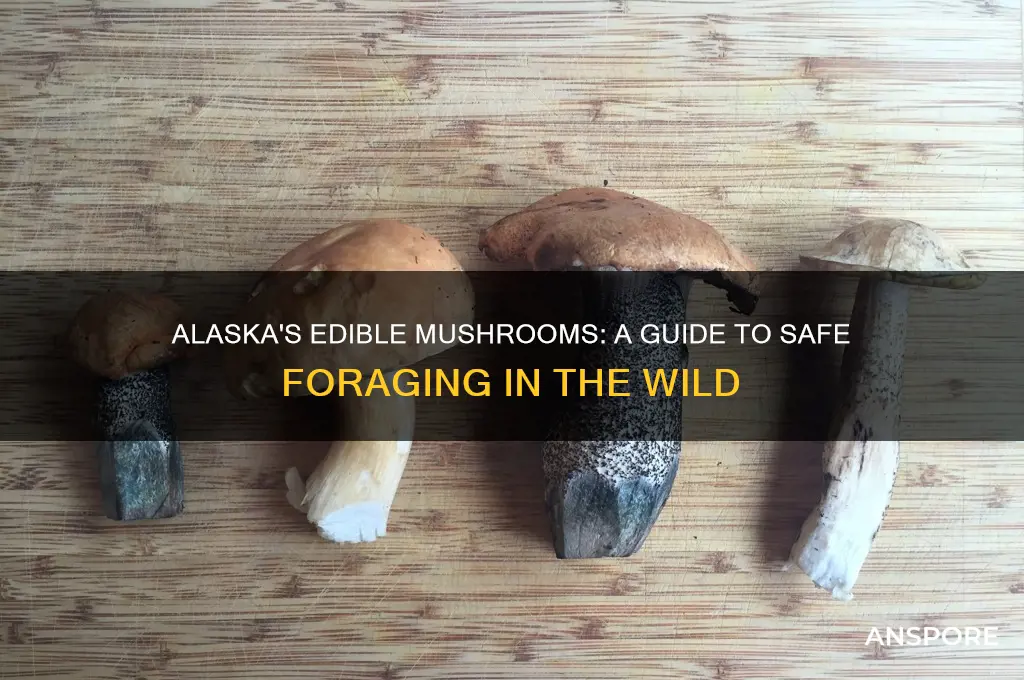

Alaska’s diverse ecosystems, ranging from dense forests to tundra, support a variety of edible mushrooms, making it a fascinating destination for foragers. Among the most commonly found edible species are the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), prized for its fruity aroma and golden hue, and the Boletus family, including the King Bolete (*Boletus edulis*), known for its meaty texture and rich flavor. Additionally, the Morel (*Morchella* spp.) thrives in Alaska’s fire-scarred forests, offering a unique, honeycomb-like cap. However, foragers must exercise caution, as toxic look-alikes such as the Destroying Angel (*Amanita* spp.) and False Morel (*Gyromitra* spp.) also inhabit the region. Proper identification, guided by local experts or field guides, is essential to safely enjoy Alaska’s bountiful fungal treasures.

Explore related products

$10.44 $19.99

What You'll Learn

- Common Edible Mushrooms: Chanterelles, morels, oyster mushrooms, and lion's mane are popular Alaskan edible varieties

- Toxic Look-Alikes: Beware of false morels, poisonous amanitas, and jack-o’-lanterns that resemble edible species

- Foraging Safety Tips: Always use a guide, check spore prints, and avoid damaged or old mushrooms

- Seasonal Availability: Most edible mushrooms in Alaska are found in late summer to early fall

- Legal Foraging Rules: Check state regulations and avoid protected areas when harvesting wild mushrooms

Common Edible Mushrooms: Chanterelles, morels, oyster mushrooms, and lion's mane are popular Alaskan edible varieties

Alaska's forests and tundra are a treasure trove for foragers, offering a variety of edible mushrooms that thrive in its unique climate. Among these, chanterelles, morels, oyster mushrooms, and lion’s mane stand out as the most sought-after varieties. Each of these mushrooms not only adds culinary depth but also boasts distinct flavors and textures that make them favorites among both amateur foragers and seasoned chefs.

Chanterelles, with their golden, trumpet-like caps, are a hallmark of Alaskan forests. They are often found in coniferous and deciduous woods, particularly under spruce trees. Their fruity aroma and chewy texture make them a versatile ingredient in soups, sauces, and sautéed dishes. When foraging, look for their forked gills and wavy caps, but beware of false chanterelles, which lack the true chanterelle’s apricot scent. Always cook chanterelles thoroughly, as consuming them raw can cause digestive discomfort.

Morels, prized for their honeycomb-like caps, are a springtime delicacy in Alaska. They typically emerge in recently burned areas or near cottonwood trees. Their earthy, nutty flavor pairs well with creamy sauces, pasta, or simply sautéed in butter. However, proper identification is critical, as morels resemble toxic false morels. Always cut them in half to ensure the hollow interior is free of folds or chambers. Drying morels preserves their flavor and extends their shelf life, making them a valuable pantry staple.

Oyster mushrooms, named for their shellfish-like appearance, are prolific growers on decaying wood. They are one of the easiest mushrooms to identify, with their fan-shaped caps and short stems. These mushrooms have a mild, slightly sweet flavor that complements stir-fries, soups, and even as a meat substitute in vegetarian dishes. Foraging for oyster mushrooms is relatively safe, as they have few toxic look-alikes, but always avoid specimens growing on coniferous wood, as they may be bitter.

Lion’s mane, a shaggy, white mushroom resembling a pom-pom or cascading icicles, is both a culinary and medicinal marvel. Found on hardwood trees, it has a texture reminiscent of crab or lobster when cooked, making it a popular vegan seafood substitute. Its mild, slightly sweet flavor pairs well with garlic, butter, and herbs. Beyond the kitchen, lion’s mane is celebrated for its cognitive benefits, with studies suggesting it may support nerve regeneration and brain health. When foraging, ensure the mushroom is fresh and free of discoloration, as older specimens can become mushy.

In Alaska, foraging for these mushrooms is not just a culinary pursuit but a connection to the wilderness. However, safety is paramount. Always carry a reliable field guide, consult local experts, and never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identification. With proper knowledge and caution, chanterelles, morels, oyster mushrooms, and lion’s mane can transform your meals and deepen your appreciation for Alaska’s natural bounty.

Edible or Poisonous: Unveiling the Truth About Most Mushrooms

You may want to see also

Toxic Look-Alikes: Beware of false morels, poisonous amanitas, and jack-o’-lanterns that resemble edible species

Alaska's forests and meadows are a treasure trove for foragers, offering a variety of edible mushrooms like morels, chanterelles, and oyster mushrooms. However, this bounty comes with a perilous caveat: toxic look-alikes that can deceive even experienced hunters. Among the most notorious imposters are false morels, poisonous amanitas, and jack-o-lanterns, each mimicking edible species in ways that demand careful scrutiny.

False morels, often mistaken for true morels due to their brain-like appearance, contain a toxin called gyromitrin. When ingested, gyromitrin converts to monomethylhydrazine, a compound used in rocket fuel. Symptoms of poisoning include nausea, vomiting, and in severe cases, seizures or liver damage. To distinguish false morels from their edible counterparts, examine the cap structure: true morels have a honeycomb pattern with pits and ridges, while false morels appear more wrinkled and uneven. A simple rule of thumb: if the mushroom’s cap is a single, hollow chamber, avoid it.

Poisonous amanitas, such as the death cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and destroying angel (*Amanita bisporigera*), are perhaps the most infamous toxic mushrooms. They resemble edible species like the button mushroom or meadow mushroom, with their smooth caps and white gills. However, amanitas contain amatoxins, which cause severe gastrointestinal distress within 6–24 hours of ingestion, followed by potential liver and kidney failure. Fatalities are not uncommon. Key identifiers include a cup-like volva at the base and a ring on the stem, though these features may not always be visible. When in doubt, avoid any mushroom with these characteristics.

Jack-o-lanterns (*Omphalotus olearius*) are another deceptive species, often mistaken for chanterelles due to their bright orange color and wavy caps. Unlike chanterelles, jack-o-lanterns grow in clusters on wood and emit a faint glow in the dark. They contain illudins, toxins that cause severe cramps, vomiting, and diarrhea. To differentiate, examine the gills: chanterelles have forked, false gills, while jack-o-lanterns have true, sharp gills. Additionally, chanterelles have a fruity aroma, whereas jack-o-lanterns may smell spicy or unpleasant.

To safely forage in Alaska, adopt a meticulous approach. Always cross-reference findings with multiple field guides or apps, and when in doubt, consult an expert. Avoid consuming any mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity. Cooking does not neutralize toxins in poisonous species, so proper identification is paramount. Finally, start with easily identifiable species like oyster mushrooms or birch boletes before attempting more challenging varieties. The thrill of foraging should never outweigh the risk of misidentification.

Exploring Edible Mushrooms: Health Benefits, Culinary Uses, and Nutritional Value

You may want to see also

Foraging Safety Tips: Always use a guide, check spore prints, and avoid damaged or old mushrooms

Alaska's forests and meadows are a treasure trove for foragers, offering a variety of edible mushrooms like the prized Chanterelles, Boletus, and Morels. However, the thrill of discovery comes with significant risks. Always use a guide—whether a knowledgeable human companion or a reliable field guide—to ensure accurate identification. Alaska’s mushroom species can be deceptively similar, and even experienced foragers consult references to avoid deadly look-alikes like the Destroying Angel or Galerina. A guide provides context-specific knowledge, such as how Alaska’s Chanterelles often thrive in spruce forests, while false look-alikes like the Jack-O-Lantern fungus grow in clusters and cause severe gastrointestinal distress.

Once you’ve collected a specimen, check the spore print to confirm its identity. This simple technique involves placing the mushroom cap gills-down on a white piece of paper overnight. The color of the spores—ranging from white to brown, black, or even pink—is a critical identifier. For example, Boletus mushrooms in Alaska typically produce olive-brown spore prints, while Amanita species may produce white ones. Cross-reference this with your guide to narrow down possibilities. Note that spore prints are not foolproof but are a valuable tool when combined with other characteristics like gill structure, cap color, and habitat.

Avoid damaged or old mushrooms as they can be misleading or dangerous. A mushroom past its prime may lose key identifying features, such as vibrant color or firm texture, making it harder to classify. Worse, decaying mushrooms can harbor bacteria or toxins not present in fresh specimens. For instance, older Boletus mushrooms may develop a spongy texture and lose their distinctive pore pattern, while Morels can become infested with insects or mold. Always inspect your find for signs of wear, discoloration, or unusual softness, and err on the side of caution by leaving it behind.

Foraging in Alaska requires respect for both the environment and your own safety. Combine these tips—using a guide, checking spore prints, and avoiding compromised specimens—to minimize risk. Remember, no meal is worth poisoning. Start with easily identifiable species like Chanterelles, and gradually expand your knowledge under expert supervision. Alaska’s wild mushrooms are a culinary delight, but their beauty lies in their complexity—approach them with humility, preparation, and precision.

Identifying Edible Mushrooms in Ontario: A Safe Foraging Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Seasonal Availability: Most edible mushrooms in Alaska are found in late summer to early fall

Alaska's mushroom season is a fleeting but bountiful window, primarily confined to late summer and early fall. This timing coincides with the state's cooler, moist conditions, which are ideal for fungal growth. Foragers know to mark their calendars for August through October, when the forests come alive with a variety of edible species. The golden chanterelles, for instance, emerge in late August, their vibrant color contrasting with the mossy understory. Similarly, the prized king bolete begins to appear in September, its meaty texture making it a favorite among chefs and home cooks alike. Understanding this seasonal rhythm is crucial for anyone looking to harvest Alaska's wild mushrooms safely and successfully.

The late summer to early fall timeframe isn’t arbitrary; it’s a biological response to Alaska’s unique climate. As temperatures drop and rainfall increases, the mycelium networks beneath the soil spring into action, producing fruiting bodies above ground. This period also follows the peak of mosquito season, making foraging more enjoyable. However, the narrow window demands efficiency. Foragers must act swiftly, as frosts can quickly end the season. A practical tip: monitor local weather patterns and plan trips after a few days of rain, as this often triggers mushroom growth. Additionally, keep an eye on daylight hours, as shorter days signal the season’s close.

Comparing Alaska’s mushroom season to regions further south highlights its distinctiveness. In the Pacific Northwest, for example, mushrooms like morels appear in spring, while Alaska’s cooler climate delays this process. This delay isn’t a drawback but a feature, as it allows for a concentrated harvest period. Foragers in Alaska can focus their efforts on a few intense weeks rather than spreading them across months. This intensity fosters a sense of community, with local clubs often organizing group forays during peak season. For newcomers, joining these groups can provide invaluable guidance on identifying species and navigating Alaska’s rugged terrain.

A cautionary note is essential: not all mushrooms that appear during this season are safe to eat. The deadly Amanita species, for instance, also thrives in late summer and early fall. Proper identification is non-negotiable. Carry a field guide or use a trusted app, but never rely solely on digital tools. A common rule of thumb is to consume only mushrooms that have been verified by an expert. For those new to foraging, start by targeting easily identifiable species like chanterelles or oyster mushrooms. Avoid anything with white gills or a bulbous base, as these are red flags for toxic varieties.

Finally, the seasonal availability of Alaska’s edible mushrooms offers more than just a culinary opportunity—it’s a chance to connect with the state’s natural rhythms. Foraging during this time encourages mindfulness and respect for the environment. Always practice sustainable harvesting by using a knife to cut mushrooms at the base, leaving the mycelium intact for future growth. Preserve your finds by drying or freezing them, extending their usability beyond the short season. By embracing these practices, foragers can enjoy Alaska’s wild bounty while ensuring its longevity for years to come.

Is Turkey Tail Mushroom Edible? Benefits, Risks, and Safe Consumption Tips

You may want to see also

Legal Foraging Rules: Check state regulations and avoid protected areas when harvesting wild mushrooms

Alaska's vast wilderness offers a treasure trove of edible mushrooms, from the prized morels to the versatile chanterelles. However, before you venture into the woods with your basket, it’s crucial to understand the legal boundaries of foraging. Alaska’s regulations are designed to protect both the environment and foragers, ensuring sustainable practices and safety. Ignoring these rules can lead to fines, habitat destruction, or even poisoning if you harvest in the wrong place.

First, familiarize yourself with Alaska’s state regulations on foraging. While Alaska is generally permissive for personal-use mushroom harvesting on public lands, specific areas like national parks, wildlife refuges, and state-designated protected zones are off-limits. For instance, Denali National Park strictly prohibits foraging of any kind. Additionally, some areas may require permits or have quantity limits, especially for commercial harvesting. The Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR) provides detailed guidelines, so check their website or contact local forestry offices before heading out.

Protected areas aren’t just bureaucratic red tape—they serve a critical ecological purpose. Foraging in these zones can disrupt fragile ecosystems, endanger rare species, and degrade habitats. For example, trampling through a protected wetland while hunting for mushrooms can harm plant life and disturb wildlife. Even seemingly harmless actions, like over-harvesting in a single area, can deplete mushroom populations and disrupt the mycorrhizal networks essential for forest health. Respecting these boundaries ensures that Alaska’s natural resources remain abundant for future generations.

Practical tips can make your foraging experience both legal and rewarding. Always carry a map and GPS device to avoid wandering into restricted areas. Stick to trails to minimize habitat damage, and harvest mushrooms sustainably by leaving some behind to spore and regenerate. If you’re unsure about a location’s status, err on the side of caution and choose another spot. Remember, the goal is to enjoy Alaska’s bounty without compromising its integrity.

In conclusion, legal foraging in Alaska requires diligence and respect for the land. By checking state regulations, avoiding protected areas, and practicing sustainable harvesting, you can safely enjoy the state’s edible mushrooms while preserving its natural beauty. Foraging isn’t just about the harvest—it’s about stewardship and ensuring that Alaska’s wild resources thrive for years to come.

Are Giant Prince Mushrooms Edible? A Comprehensive Guide to Safety

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Alaska is home to several edible mushrooms, including the Chanterelle (*Cantharellus cibarius*), Hedgehog Mushroom (*Hydnum repandum*), Oyster Mushroom (*Pleurotus ostreatus*), and the Velvet Foot (*Flammulina velutipes*). Always ensure proper identification before consuming.

Yes, some poisonous mushrooms in Alaska, like the Destroying Angel (*Amanita ocreata*) and False Chanterelles (*Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca*), closely resemble edible species. It’s crucial to consult a field guide or expert for accurate identification.

The prime mushroom foraging season in Alaska typically runs from late summer to early fall (August through September), when conditions are cool and moist, ideal for fungal growth.

No, it’s not safe to consume wild mushrooms without proper identification. Many species look similar, and misidentification can lead to poisoning. Always consult a knowledgeable forager or mycologist before eating any wild mushrooms.