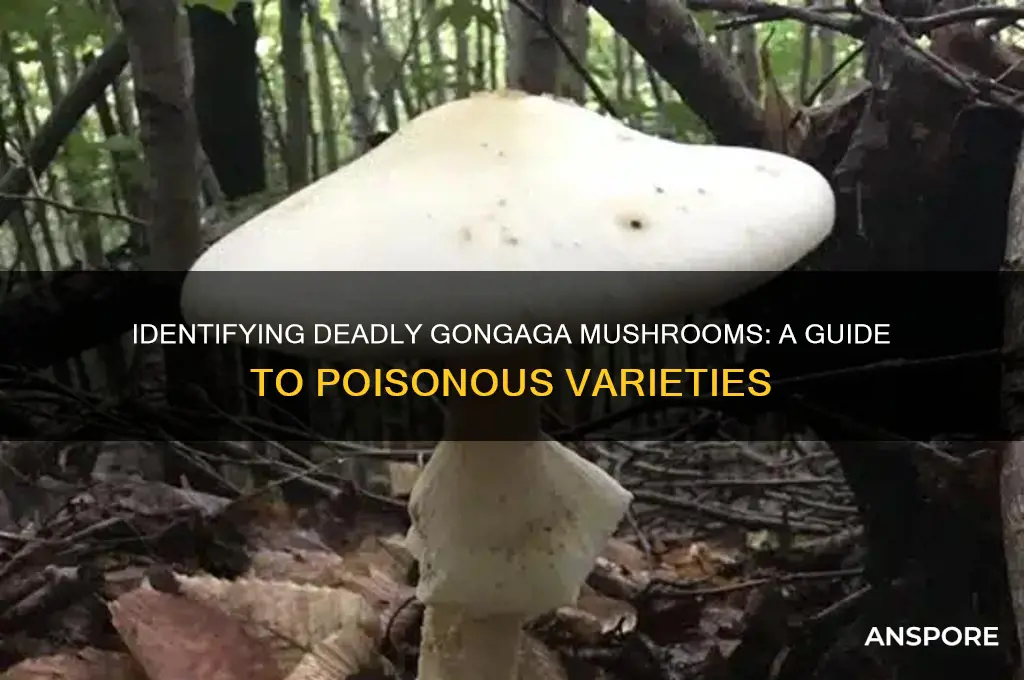

The Gongaga region is known for its diverse mushroom species, many of which are integral to local cuisine and traditional medicine. However, not all mushrooms found in this area are safe for consumption. Among the various types, one particular Gongaga mushroom stands out as highly poisonous, posing a significant risk to those who mistake it for an edible variety. Identifying this toxic species is crucial for foragers and enthusiasts to avoid severe health consequences, making it essential to understand its distinct characteristics and habitat.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Identifying Toxic Gongaga Mushrooms

In the lush, mist-shrouded forests of Gongaga, mushroom foraging can be both rewarding and perilous. Among the diverse species, the Deathveil Cap (*Gongaga venefica*) stands out as the most notorious toxin producer. Its smooth, dark purple cap and bioluminescent gills often lure unsuspecting gatherers, but ingesting even a small fragment (0.5 grams) can induce severe gastrointestinal distress within 30 minutes. Unlike its benign cousin, the Moonlight Parasol, which has a scalloped edge and emits a faint lavender scent, the Deathveil Cap lacks any distinct odor, making olfactory identification unreliable. Always carry a magnifying lens to examine gill structure—toxic varieties typically have tightly packed, iridescent gills.

Foraging safely requires a systematic approach. Start by noting habitat preferences: toxic Gongaga mushrooms thrive in damp, shadowy areas near decaying wood, while edible species favor open clearings. Next, assess spore color by placing the cap on paper overnight; toxic varieties produce black spores, whereas edible ones yield white or cream-colored prints. If unsure, perform a potassium hydroxide (KOH) test: apply a drop of 3% KOH solution to the cap; toxic mushrooms will turn bright green within 10 seconds due to a unique alkaloid reaction. This test, though definitive, requires caution—KOH is caustic and should be handled with gloves.

Children and pets are particularly vulnerable to toxic Gongaga mushrooms due to their lower body mass. A single Deathveil Cap can be fatal to a child under 12 or a small dog. Educate family members to avoid any mushroom with a “skirted stem”—a ring-like structure often present in toxic varieties. If ingestion is suspected, administer activated charcoal (50 grams for adults, 25 grams for children) within 30 minutes to bind toxins, then seek immediate medical attention. Hospitals in Gongaga regions often stock antitoxins specific to *G. venefica*, but early intervention is critical.

Comparing toxic and edible Gongaga mushrooms reveals subtle yet crucial differences. The Ethereal Fan (*Gongaga lumina*), an edible variety, has a translucent cap that glows blue under UV light, whereas the Deathveil Cap remains purple. Texture also matters: toxic species have a slippery, almost gelatinous cap surface when moist, while edible ones feel matte. Foraging groups should designate a “mushroom expert” armed with a field guide and testing kit to verify finds. Remember, no folklore test (e.g., “insect avoidance”) is foolproof—rely solely on scientific methods.

Finally, preservation techniques can inadvertently mask toxicity. Drying toxic mushrooms does not neutralize their poisons; in fact, it concentrates them. If you’re preparing Gongaga mushrooms for consumption, blanch them in boiling water for 5 minutes to deactivate potential toxins, then discard the water. Store foraged specimens in separate containers labeled with collection dates and locations. Foraging should be a mindful practice, blending curiosity with caution—after all, the line between a feast and a fatality is often thinner than a mushroom’s veil.

Identifying Poisonous Mushrooms: Common Traits and Key Characteristics

You may want to see also

Symptoms of Poisoning

The Gongaga mushroom, a term often associated with the fictional world of Final Fantasy VII, doesn't have a real-world counterpart, but the topic of poisonous mushrooms and their symptoms is a critical one. In reality, many mushrooms can cause severe poisoning, and recognizing the symptoms early can be life-saving. For instance, the Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) is one of the most toxic mushrooms, responsible for the majority of fatal mushroom poisonings worldwide. Its symptoms can be deceptive, often delayed, and initially mimic common gastrointestinal issues.

Analytical Perspective:

Poisoning symptoms typically manifest in stages, depending on the toxin involved. Amatoxins, found in the Death Cap, cause a biphasic reaction. The first phase begins 6–24 hours after ingestion, with symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These symptoms may subside, giving a false sense of recovery. However, the second phase, occurring 2–4 days later, is far more severe, involving liver and kidney failure, jaundice, seizures, and coma. Dosage matters—as little as half a Death Cap can be fatal for an adult, while children are at higher risk due to their lower body weight.

Instructive Approach:

If you suspect mushroom poisoning, immediate action is crucial. Do not wait for symptoms to worsen. Call emergency services or a poison control center right away. Preserve a sample of the mushroom for identification, but do not induce vomiting unless advised by a professional. For mild cases, activated charcoal may be administered to prevent toxin absorption. In severe cases, hospitalization is mandatory, often involving intravenous fluids, liver support, and, in extreme cases, a liver transplant.

Comparative Insight:

Not all poisonous mushrooms act the same way. For example, the hallucinogenic effects of psilocybin mushrooms are vastly different from the lethal effects of amatoxins. Psilocybin poisoning typically causes psychological symptoms like hallucinations, anxiety, and paranoia, which resolve within 6–12 hours. In contrast, mushrooms containing orellanine, like the Fool’s Webcap (*Cortinarius orellanus*), cause delayed kidney failure, with symptoms appearing 3–14 days after ingestion. Understanding these differences is key to appropriate treatment.

Descriptive Narrative:

Imagine a scenario where a hiker misidentifies a Death Cap as an edible mushroom. Within hours, they experience intense abdominal pain and uncontrollable vomiting. By the third day, their skin turns yellow, and they become disoriented. Without urgent medical intervention, this could lead to organ failure and death. This grim picture underscores the importance of proper mushroom identification and awareness of poisoning symptoms. Always consult a mycologist or use a reliable field guide before consuming wild mushrooms.

Practical Takeaway:

Prevention is the best defense against mushroom poisoning. Avoid consuming wild mushrooms unless you are absolutely certain of their identity. Teach children to never touch or eat mushrooms found outdoors. If poisoning occurs, time is of the essence. Quick recognition of symptoms and prompt medical attention can mean the difference between recovery and tragedy. Remember, when in doubt, throw it out.

Are Haymaker Mushrooms Poisonous? Uncovering the Truth About Their Safety

You may want to see also

Safe Mushroom Look-Alikes

In the lush forests of Gongaga, mushroom foragers often encounter the striking Amanita muscaria, known for its vibrant red cap and white speckles. While this iconic fungus is psychoactive rather than deadly, its doppelgänger, the Amanita bisporigera, is a silent killer. The latter, often mistaken for its famous cousin, contains amatoxins that can cause liver failure within 24 hours. This highlights a critical foraging principle: safe look-alikes exist, but their similarities can be deceiving. For instance, the edible Fly Agaric (Amanita muscaria) shares the same habitat and appearance with its lethal relative, differing only in spore structure—a detail invisible to the untrained eye.

To avoid such pitfalls, focus on key identifiers beyond color and shape. The Lactarius deliciosus, a prized edible mushroom, resembles the toxic Russula emetica in its orange-hued cap and sturdy stem. However, the former exudes a milky latex when cut, while the latter’s flesh bruises bright red—a telltale sign of toxicity. Always carry a knife and test for these reactions; a simple scratch can save a life. Additionally, note habitat preferences: Russula species often grow in coniferous forests, while Lactarius thrives in mixed woodlands. Cross-referencing these traits reduces the risk of misidentification.

Foraging safely also requires temporal awareness. The edible Chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius) and the toxic Jack-O’-Lantern (Omphalotus olearius) both glow in bioluminescent displays at night. However, the latter grows in clusters on decaying wood, while chanterelles prefer mossy soil. Time your harvest during daylight to avoid confusion, and remember: bioluminescence is not an indicator of edibility. If in doubt, skip the specimen entirely—no meal is worth the risk of ingesting illudin S, the toxin in Jack-O’-Lanterns that causes severe gastrointestinal distress.

Lastly, regional knowledge is indispensable. In Gongaga, the Puffball (Calvatia gigantea) is a beloved edible, but its immature form resembles the deadly Amanita ocreata. The latter, known as the “Destroying Angel,” has a bulbous base and a cup-like volva—features absent in young puffballs. To test, slice the mushroom in half; a puffball should have a solid, white interior, while Amanita species have gills. Foraging classes or local mycological societies can provide hands-on training, ensuring you distinguish between these life-or-death look-alikes. Always prioritize caution over curiosity in the wild.

Florida's Foraging Risks: Poisonous Oyster Mushroom Look-Alikes Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Habitat of Poisonous Varieties

Poisonous Gongaga mushrooms thrive in environments that offer a delicate balance of moisture, shade, and decaying organic matter. These fungi are often found in dense, humid forests where the canopy above blocks direct sunlight, creating a cool, damp microclimate. The forest floor, rich with fallen leaves, rotting wood, and decomposing plant material, provides the nutrients these mushrooms need to flourish. Unlike their edible counterparts, which may prefer more open or disturbed areas, poisonous varieties tend to cluster in undisturbed, mature ecosystems. This habitat preference makes them less likely to be encountered by casual foragers but more dangerous when they are.

Identifying the habitat of poisonous Gongaga mushrooms requires a keen eye for environmental cues. Look for areas with high humidity, such as near streams, wetlands, or in valleys where moisture accumulates. These mushrooms often grow in symbiotic relationships with specific tree species, particularly conifers and hardwoods like oak and beech. Their mycelium networks thrive in the soil beneath these trees, drawing nutrients from the roots while contributing to the ecosystem. Foragers should avoid harvesting mushrooms in these zones, especially during rainy seasons when fungal growth peaks.

A comparative analysis of habitats reveals that poisonous Gongaga mushrooms are less adaptable than their non-toxic relatives. While edible varieties can often be found in a range of environments, from meadows to urban parks, poisonous species are highly specialized. They require stable, long-established habitats with minimal human interference. This specificity makes them less common but more concentrated in their preferred areas. For instance, a single patch of old-growth forest might host a dense cluster of poisonous mushrooms, while nearby clearings yield none.

Practical tips for avoiding poisonous Gongaga mushrooms include staying on designated trails and avoiding foraging in deep, undisturbed forests. If you must venture into their habitat, carry a field guide or use a reliable mushroom identification app. Note the surrounding vegetation and soil conditions, as these can provide clues about the likelihood of encountering toxic species. Never consume a mushroom unless you are 100% certain of its identity, and remember that even experienced foragers can make mistakes. When in doubt, leave it out.

In conclusion, understanding the habitat of poisonous Gongaga mushrooms is crucial for safe foraging. Their preference for mature, humid forests with specific tree associations sets them apart from edible varieties. By recognizing these environmental cues and adopting cautious practices, foragers can minimize the risk of accidental poisoning. Knowledge of their habitat not only protects individuals but also preserves these fascinating organisms in their natural ecosystems.

Purple Mushrooms and Dogs: Are They a Toxic Danger?

You may want to see also

Prevention and First Aid Tips

In Gongaga, where mushroom foraging is a cherished tradition, misidentifying a poisonous species can have dire consequences. The Death Cap (*Amanita phalloides*) and Destroying Angel (*Amanita bisporigera*) are two deadly varieties often mistaken for edible ones due to their similar appearance. Prevention begins with education: always cross-reference findings with a reliable field guide or consult a mycologist. Avoid mushrooms with white gills, a bulbous base, or a ring on the stem—common traits of toxic species.

If ingestion occurs, time is critical. First aid starts with immediate contact to a poison control center or emergency services. Induce vomiting only if advised by a professional, as it can worsen certain poisonings. Administer activated charcoal (available over-the-counter) if accessible within an hour of ingestion, as it binds toxins in the stomach. For children under 12, use 25–50 grams; adults should take 50–100 grams dissolved in water. Monitor symptoms like nausea, diarrhea, or jaundice, which may appear 6–24 hours post-ingestion, and seek urgent medical care.

Prevention extends beyond the forest. Teach children to "admire, not pick" wild mushrooms, emphasizing the dangers of unknown species. For foragers, carry a knife to cut samples for identification, preserving the base and cap for analysis. Avoid consuming alcohol post-ingestion, as it accelerates toxin absorption. Lastly, cook all wild mushrooms thoroughly, though this does not neutralize all toxins—a common misconception.

Comparatively, Gongaga’s poisonous mushrooms share traits with edible varieties, making reliance on folklore risky. For instance, the False Morel (*Gyromitra esculenta*) resembles the edible morel but contains gyromitrin, a toxin causing gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms. Unlike the Death Cap’s delayed onset, False Morel poisoning appears within 6–12 hours. Treatment includes gastric lavage and administration of activated charcoal, followed by medical monitoring for liver damage.

In conclusion, prevention hinges on knowledge and caution, while first aid relies on swift, informed action. Equip yourself with a field guide, avoid risky assumptions, and prioritize professional advice in emergencies. Gongaga’s mushrooms are a treasure, but their beauty masks dangers that demand respect and preparedness.

Are Scotch Bonnet Mushrooms Poisonous to Dogs? A Safety Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Gongaga mushroom known as *Amanita gongagaensis* is considered poisonous and should be avoided.

The poisonous *Amanita gongagaensis* typically has a bright red cap with white spots and a distinct ring on its stem.

No, not all Gongaga mushrooms are poisonous. Only specific species, like *Amanita gongagaensis*, are toxic.

Symptoms can include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dizziness, and in severe cases, liver or kidney damage.

No, it is not safe to consume any Gongaga mushroom unless you are absolutely certain of its species and edibility. Always consult an expert.