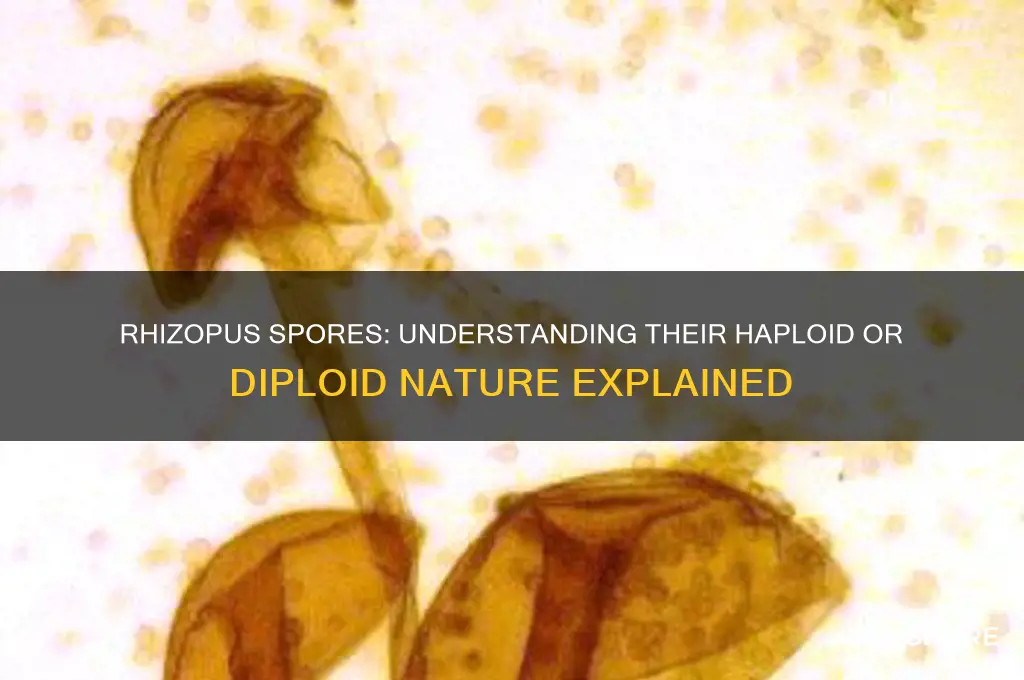

Rhizopus, a common genus of filamentous fungi belonging to the Zygomycota phylum, plays a significant role in various ecological and industrial processes. Understanding the life cycle of Rhizopus is crucial for comprehending its reproductive strategies and genetic makeup. A central question in this context is whether Rhizopus spores are haploid or diploid. This inquiry delves into the fundamental aspects of fungal biology, particularly the alternation of generations and the ploidy levels of different life stages. Rhizopus exhibits a haploid-dominant life cycle, where the majority of its existence is spent in the haploid phase, with diploid stages being relatively short-lived. Spores, which are the primary dispersal units, are typically haploid, arising from the fragmentation of hyphae or the formation of sporangiospores. However, during sexual reproduction, diploid zygospores are formed, which later undergo meiosis to restore the haploid state. Thus, the ploidy of Rhizopus spores is primarily haploid, reflecting the organism's life cycle dynamics.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Rhizopus Life Cycle Overview: Understanding the stages of Rhizopus growth and reproduction

- Sporangiospore Formation: How haploid spores develop within the sporangium

- Zygospores and Diploid Stage: Fusion of gametangia forming diploid zygospores

- Haploid vs. Diploid Spores: Distinguishing sporangiospores (haploid) from zygospores (diploid)

- Genetic Implications: Role of haploid and diploid stages in Rhizopus evolution

Rhizopus Life Cycle Overview: Understanding the stages of Rhizopus growth and reproduction

Rhizopus, a common mold found on decaying organic matter, exhibits a life cycle that is both fascinating and crucial for its survival and propagation. Central to understanding this cycle is the question of whether Rhizopus spores are haploid or diploid. Spores, the primary means of dispersal and survival, are haploid, containing a single set of chromosomes. This haploid state is a defining feature of the asexual phase of the Rhizopus life cycle, known as the vegetative phase. During this stage, the fungus grows rapidly, producing a network of hyphae that absorb nutrients from its substrate, such as bread or fruits. The haploid nature of the spores ensures genetic diversity through subsequent sexual reproduction when conditions allow.

The life cycle of Rhizopus begins with spore germination, a process triggered by moisture and suitable temperature (typically 25–30°C). Once a haploid spore lands on a favorable substrate, it absorbs water, swells, and germinates, forming a germ tube that develops into a network of hyphae. These hyphae are also haploid and grow vegetatively, branching extensively to maximize nutrient uptake. This stage is entirely asexual, with the fungus relying on mitosis to proliferate. The hyphae eventually produce sporangia, structures that contain thousands of haploid spores. These spores are then released into the environment, ready to colonize new substrates or survive harsh conditions.

Sexual reproduction in Rhizopus occurs under specific environmental cues, such as nutrient depletion or overcrowding. When two compatible haploid hyphae (of opposite mating types) come into contact, they fuse in a process called plasmogamy, forming a heterokaryotic cell with two distinct nuclei. This is followed by karyogamy, where the nuclei fuse to form a diploid zygote. The zygote then undergoes meiosis to restore the haploid state, producing haploid spores within a thick-walled zygosporangium. This diploid phase is transient but critical for genetic recombination, enhancing the species' adaptability. The zygosporangium can remain dormant for extended periods, germinating when conditions improve to release new haploid spores.

Understanding the stages of Rhizopus growth and reproduction is essential for practical applications, such as food preservation and fungal control. For instance, preventing spore germination by maintaining dry conditions or low temperatures can inhibit mold growth on stored foods. Conversely, in biotechnology, controlled conditions can encourage spore production for industrial uses, such as in the production of enzymes or organic acids. The haploid nature of Rhizopus spores also makes them valuable in genetic studies, as their simplicity facilitates research on fungal genetics and evolution.

In summary, the Rhizopus life cycle is a dynamic interplay of haploid and diploid phases, each serving distinct purposes. Haploid spores and hyphae dominate the asexual, vegetative growth, ensuring rapid colonization and nutrient acquisition. The brief diploid phase, triggered by specific conditions, promotes genetic diversity through sexual reproduction. This dual strategy allows Rhizopus to thrive in diverse environments, from kitchens to forests, making it a resilient and ubiquitous organism. By dissecting these stages, we gain insights into fungal biology and practical tools for managing this mold in various contexts.

How Mold Spores Spread: Understanding Airborne Contamination Risks

You may want to see also

Sporangiospore Formation: How haploid spores develop within the sporangium

Rhizopus, a common mold found on decaying organic matter, produces spores through a fascinating process known as sporangiospore formation. This mechanism ensures the continuation of the species by generating haploid spores within a specialized structure called the sporangium. Understanding how these haploid spores develop is crucial for grasping the life cycle of Rhizopus and its role in ecosystems.

The process begins with the maturation of the sporangium, a spherical or oval structure located at the tip of a stalk called the sporangiophore. Inside the sporangium, haploid nuclei undergo multiple rounds of mitosis, a type of cell division that results in genetically identical daughter nuclei. These nuclei are then surrounded by cytoplasm to form individual sporangiospores. Unlike diploid spores, which contain two sets of chromosomes, each sporangiospore in Rhizopus carries a single set, making them haploid. This haploid state is essential for the sexual reproduction phase when spores from different individuals combine to form a diploid zygote.

A key step in sporangiospore formation is the breakdown of the sporangium wall, which allows the mature spores to be released into the environment. This dispersal is often facilitated by air currents, ensuring the spores can colonize new substrates. For instance, in laboratory settings, researchers observe this process by culturing Rhizopus on nutrient-rich media, where sporangia develop within 24–48 hours under optimal conditions (25–30°C and high humidity). Practical tips for observing this include using a magnifying glass or microscope to track the development of sporangia and the subsequent release of spores.

Comparatively, the haploid nature of Rhizopus spores contrasts with organisms like fungi that produce diploid spores. This distinction highlights the evolutionary strategy of Rhizopus, which prioritizes rapid colonization and adaptation through genetic diversity. By producing haploid spores, Rhizopus ensures that genetic recombination occurs during sexual reproduction, increasing the species’ ability to survive in varying environments.

In conclusion, sporangiospore formation in Rhizopus is a precise and efficient process that results in the development of haploid spores within the sporangium. This mechanism not only ensures the species’ survival but also provides a model for studying fungal life cycles. Whether in a classroom or a research lab, observing this process offers valuable insights into the biology of molds and their ecological significance.

Can Most Bacteria Form Spores? Unveiling Microbial Survival Strategies

You may want to see also

Zygospores and Diploid Stage: Fusion of gametangia forming diploid zygospores

Rhizopus, a common mold found on decaying organic matter, exhibits a fascinating reproductive cycle that hinges on the formation of zygospores. These structures are pivotal in the life cycle of Rhizopus, marking the transition from haploid to diploid stages. The process begins with the fusion of gametangia, specialized structures that house haploid gametes. When two compatible gametangia merge, their haploid nuclei unite, forming a diploid zygote within a thick-walled zygospore. This zygospore is not merely a product of sexual reproduction but also a resilient survival structure, capable of enduring harsh environmental conditions.

The fusion of gametangia is a highly regulated process, ensuring that only compatible individuals can form zygospores. This compatibility is governed by mating types, analogous to the sex determination systems in higher organisms. In Rhizopus, the gametangia are typically of two types, often referred to as "+" and "–", and only opposite types can fuse. This mechanism prevents inbreeding and promotes genetic diversity, a critical factor in the adaptability and survival of the species. Once fusion occurs, the resulting zygospore undergoes a period of dormancy, during which the diploid nucleus may undergo karyogamy and meiosis, eventually producing haploid spores that can germinate under favorable conditions.

From a practical standpoint, understanding the diploid stage of Rhizopus is essential for various applications, including biotechnology and food production. For instance, zygospores’ resistance to desiccation and extreme temperatures makes them valuable in the study of stress tolerance mechanisms. Researchers can isolate and analyze the genetic and biochemical pathways activated during zygospore formation to develop strategies for preserving microorganisms or enhancing crop resilience. Additionally, the diploid stage is crucial in genetic studies, as it allows for the mapping of traits and the identification of genes responsible for specific characteristics, such as antibiotic production or metabolic efficiency.

Comparatively, the diploid zygospore stage in Rhizopus contrasts with the haploid-dominant life cycles of many other fungi. While species like Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) spend most of their life cycle in the haploid state, Rhizopus emphasizes the diploid phase as a key survival and reproductive strategy. This difference highlights the evolutionary diversity of fungal life cycles and the adaptive advantages of each approach. For educators and students, exploring these contrasts provides a rich opportunity to delve into the principles of genetics, evolution, and ecology, using Rhizopus as a model organism to illustrate complex biological concepts.

In conclusion, the formation of diploid zygospores through the fusion of gametangia is a cornerstone of Rhizopus’ reproductive strategy. This process not only ensures genetic diversity but also equips the organism with a robust mechanism for survival in challenging environments. By studying this stage, scientists and enthusiasts alike can gain insights into fundamental biological processes, with practical applications ranging from biotechnology to education. Whether in the lab or the classroom, the diploid stage of Rhizopus offers a wealth of knowledge waiting to be explored.

Are Psilocybe Spores Legal? Exploring the Legal Landscape and Implications

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Haploid vs. Diploid Spores: Distinguishing sporangiospores (haploid) from zygospores (diploid)

Rhizopus, a common mold found on bread and other organic matter, produces two distinct types of spores: sporangiospores and zygospores. Understanding the ploidy of these spores—whether they are haploid or diploid—is crucial for grasping their roles in the fungal life cycle. Sporangiospores, formed within sporangia at the tips of hyphae, are haploid. This means they contain a single set of chromosomes, making them ready for asexual reproduction and rapid dispersal. In contrast, zygospores, the product of sexual reproduction, are diploid, carrying two sets of chromosomes. This fundamental difference in ploidy reflects their distinct functions in the survival and propagation of Rhizopus.

To distinguish between these spores, consider their formation processes. Sporangiospores are produced through mitosis in the sporangium, a structure that develops at the end of a specialized hyphal branch called a sporangiophore. This asexual method ensures genetic uniformity, allowing the fungus to quickly colonize new environments. Zygospores, however, result from the fusion of two compatible gametangia—structures containing haploid nuclei—during sexual reproduction. This fusion restores diploidy, creating a zygospore that can remain dormant until favorable conditions trigger germination. The diploid state of zygospores enhances genetic diversity, a key advantage in adapting to changing environments.

Practically, identifying these spores requires observation of their morphology and context. Sporangiospores are typically smaller, lighter, and produced in vast quantities, often appearing as a dusty mass within the sporangium. They are dispersed by air currents, facilitating widespread colonization. Zygospores, on the other hand, are larger, thicker-walled, and often pigmented, providing resistance to harsh conditions. They are formed singly or in small clusters and are not dispersed but remain attached to the substrate. For researchers or enthusiasts, examining these characteristics under a microscope can provide clear evidence of their ploidy and function.

From an evolutionary perspective, the distinction between haploid and diploid spores highlights Rhizopus’s reproductive strategy. Asexual reproduction via haploid sporangiospores allows for rapid proliferation in stable environments, while sexual reproduction via diploid zygospores ensures genetic recombination and survival in adverse conditions. This dual approach maximizes the fungus’s adaptability and resilience. For instance, in a laboratory setting, inducing zygospore formation by manipulating environmental factors like nutrient availability or temperature can provide insights into fungal genetics and stress responses.

In summary, sporangiospores and zygospores in Rhizopus exemplify the contrast between haploid and diploid spores. Their ploidy, formation, and function are intricately linked to their roles in asexual and sexual reproduction, respectively. By recognizing these differences, one can better understand the life cycle of Rhizopus and its strategies for survival and propagation. Whether in a classroom, laboratory, or natural setting, this knowledge serves as a practical guide to identifying and studying these spores effectively.

Understanding Spores: Their Role, Survival Mechanisms, and Ecological Impact

You may want to see also

Genetic Implications: Role of haploid and diploid stages in Rhizopus evolution

Rhizopus, a common zygomycete fungus, exhibits a life cycle that alternates between haploid and diploid stages, a feature central to its genetic diversity and evolutionary success. Spores, the primary dispersal units, are haploid, arising from mitotic divisions in the sporangium. This haploid phase is critical for rapid colonization of new environments, as it allows for quick adaptation through genetic recombination during sexual reproduction. When two compatible haploid spores (or gametangia) fuse, they form a diploid zygote, which then undergoes meiosis to restore the haploid state. This alternation of generations ensures genetic reshuffling, a key mechanism for evolution.

The haploid stage in Rhizopus is not merely a passive phase but an active contributor to genetic variability. Haploid spores can undergo mutations, which, when beneficial, can be directly expressed due to the absence of a second allele. This increases the organism's ability to respond to selective pressures, such as nutrient scarcity or antifungal agents. For instance, studies have shown that haploid Rhizopus strains can develop resistance to fungicides like fluconazole more rapidly than diploid forms, highlighting the evolutionary advantage of the haploid phase.

In contrast, the diploid stage, though brief, plays a pivotal role in masking deleterious mutations and stabilizing the genome. Diploid zygospores, formed after gamete fusion, act as a genetic reservoir, allowing for the accumulation of beneficial mutations without immediate expression. This stage is particularly important in environments with fluctuating conditions, where genetic robustness is essential for survival. For example, diploid zygospores of Rhizopus microsporus have been observed to withstand desiccation and extreme temperatures better than their haploid counterparts, a trait linked to their genetic redundancy.

The interplay between haploid and diploid stages in Rhizopus drives its evolutionary trajectory by balancing innovation and stability. Haploid spores facilitate rapid adaptation and colonization, while diploid zygospores ensure long-term survival and genetic integrity. This dual strategy enables Rhizopus to thrive in diverse ecosystems, from soil to food spoilage environments. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for applications in biotechnology, such as optimizing Rhizopus for enzyme production or biocontrol, where manipulating life cycle stages can enhance desired traits.

Practically, researchers can exploit these genetic implications by inducing specific life cycle transitions. For instance, exposing Rhizopus cultures to stress conditions like UV radiation can increase mutation rates in the haploid phase, potentially yielding strains with improved industrial properties. Conversely, maintaining diploid zygospores under controlled conditions can preserve genetic stability, ensuring consistent performance in biotechnological processes. By leveraging the unique roles of haploid and diploid stages, scientists can steer Rhizopus evolution toward desired outcomes, whether in agriculture, food production, or medicine.

Understanding Spores: Mitosis or Meiosis Production Explained

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Rhizopus spores are haploid, as they are produced by mitosis from a haploid mycelium.

Rhizopus zygospores are diploid, formed by the fusion of two haploid gametangia during sexual reproduction.

No, Rhizopus spores are already haploid and are produced by mitosis, not meiosis.

No, the vegetative mycelium and spores are haploid, but the zygospore is diploid before undergoing meiosis to return to the haploid state.

Like many zygomycetes, Rhizopus spores are haploid, similar to other fungi in this group, while the zygospore is diploid, a common feature in their sexual reproduction cycle.