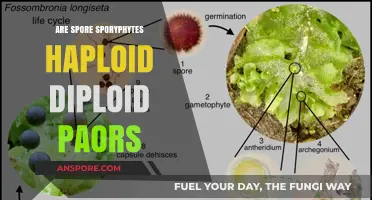

The question of whether spores are alive when released is a fascinating intersection of biology and microbiology. Spores, produced by various organisms such as bacteria, fungi, and plants, are often described as dormant, resilient structures designed to survive harsh environmental conditions. While they lack the metabolic activity and growth associated with living cells, spores retain the potential to revive and develop into new organisms under favorable conditions. This raises intriguing debates about the definition of life and the state of spores during their release, as they exist in a unique limbo between active life and suspended animation, challenging our understanding of biological vitality.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Life | Spores exhibit some, but not all, characteristics of life. They are metabolically inactive and lack growth or reproduction until germination. |

| Metabolic Activity | Dormant; minimal to no metabolic activity when released. |

| Reproduction | Cannot reproduce independently until they germinate under favorable conditions. |

| Growth | No growth occurs in the spore state; growth resumes upon germination. |

| Response to Stimuli | Limited response to environmental stimuli until germination. |

| Genetic Material | Contain genetic material (DNA/RNA) but are not actively expressing it. |

| Cell Structure | Have a protective cell wall and are highly resistant to harsh conditions. |

| Viability | Can remain viable for extended periods (years to centuries) in dormant form. |

| Germination | Become "alive" and metabolically active only after germination. |

| Scientific Consensus | Generally considered dormant or in a state of suspended animation rather than fully alive when released. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores' Metabolic State: Are spores metabolically active or dormant upon release

- Survival Mechanisms: How do spores withstand harsh environments after dispersal

- Germination Triggers: What conditions activate spores to resume growth

- Viability Testing: Methods to determine if released spores are alive

- Life Cycle Role: How do spores contribute to organism survival post-release

Spores' Metabolic State: Are spores metabolically active or dormant upon release?

Spores, upon release, enter a state of metabolic dormancy, a survival strategy honed over millennia. This quiescent condition is characterized by minimal metabolic activity, allowing spores to endure harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and nutrient scarcity. During this phase, spores reduce their energy consumption to nearly undetectable levels, preserving vital cellular components while awaiting favorable conditions for germination. This dormancy is not a passive state but a highly regulated process, with spores maintaining the capacity to sense environmental cues that signal the return of suitable growth conditions.

To understand the metabolic state of spores, consider the analogy of a hibernation chamber. Just as hibernating animals slow their metabolic processes to conserve energy, spores shut down non-essential functions while retaining the ability to reactivate rapidly when conditions improve. For instance, bacterial endospores, such as those produced by *Bacillus* species, exhibit metabolic rates reduced by 99% compared to their vegetative counterparts. This drastic slowdown is achieved through the synthesis of specialized proteins and the accumulation of protective molecules like dipicolinic acid, which stabilize cellular structures during dormancy.

From a practical standpoint, the dormant metabolic state of spores has significant implications for industries such as food preservation and healthcare. For example, in food processing, spores of *Clostridium botulinum* can survive pasteurization temperatures, posing a risk of botulism if not eradicated through more stringent methods like autoclaving. Understanding spore metabolism helps in designing effective sterilization protocols, ensuring that even dormant spores are neutralized. Similarly, in medicine, the ability of fungal spores (e.g., *Aspergillus*) to remain dormant in hospital environments underscores the need for rigorous disinfection practices to prevent nosocomial infections.

Comparatively, not all spores exhibit the same level of metabolic dormancy. Fungal spores, for instance, often retain higher metabolic activity than bacterial endospores, enabling them to disperse and germinate more rapidly under favorable conditions. This variation highlights the diversity of spore survival strategies across different organisms. While bacterial endospores prioritize long-term survival in extreme environments, fungal spores balance dormancy with readiness for rapid colonization, reflecting their distinct ecological niches.

In conclusion, spores are not metabolically active in the conventional sense upon release but exist in a state of regulated dormancy. This condition is a testament to their evolutionary ingenuity, enabling them to persist in environments that would be lethal to most life forms. By studying spore metabolism, scientists and practitioners can develop targeted strategies to control or harness these resilient entities, whether for preserving food, combating infections, or understanding microbial ecology. The dormant spore is not merely alive—it is a master of survival, poised to awaken when the time is right.

Unveiling the Fascinating Process of How Spores Are Created

You may want to see also

Survival Mechanisms: How do spores withstand harsh environments after dispersal?

Spores, upon release, enter a dormant state, yet they retain the capacity to revive under favorable conditions. This resilience is not mere chance but a product of intricate survival mechanisms honed over millennia. To understand how spores withstand harsh environments, consider their structural and metabolic adaptations, each designed to ensure longevity and viability in the face of adversity.

Structural Fortification: The First Line of Defense

Spores are encased in a robust outer layer, often composed of sporopollenin, one of nature’s most durable biopolymers. This protective shell acts as a barrier against desiccation, UV radiation, and chemical stressors. For instance, bacterial endospores have a multilayered coat that includes an exosporium, cortex, and core wall, each contributing to resistance against heat, enzymes, and physical damage. Fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus*, possess melanin in their cell walls, which absorbs UV light and neutralizes oxidative stress. This structural fortification is akin to a suit of armor, shielding the spore’s genetic material until conditions permit germination.

Metabolic Shutdown: Conserving Resources for the Long Haul

Upon dispersal, spores enter a state of metabolic dormancy, drastically reducing their energy consumption. This near-complete shutdown of cellular processes minimizes the need for nutrients and water, allowing spores to endure years, even centuries, in inhospitable environments. For example, bacterial endospores reduce their water content to as low as 10–30% of their dry weight, halting enzymatic activity and DNA replication. This metabolic quiescence is reversible; when conditions improve, spores can rapidly rehydrate and resume metabolic functions, a process triggered by specific environmental cues like temperature shifts or nutrient availability.

Repair Mechanisms: Preparing for Revival

Despite their dormancy, spores are not passive survivors. Many possess DNA repair mechanisms that activate upon rehydration, correcting damage incurred during their dormant phase. For instance, *Bacillus subtilis* endospores use specialized proteins to mend DNA lesions caused by radiation or chemicals. Similarly, fungal spores often contain high concentrations of protective proteins and antioxidants, such as superoxide dismutase, which mitigate oxidative damage. These repair mechanisms ensure that, when the time comes, spores can germinate into healthy, functional organisms.

Dispersal Strategies: Maximizing Survival Odds

The survival of spores is not solely dependent on individual resilience but also on effective dispersal strategies. Many organisms release spores in vast quantities, increasing the likelihood that at least some will land in favorable environments. For example, a single *Aspergillus* fungus can produce millions of spores, while a single fern plant releases thousands of lightweight, wind-dispersed spores. Additionally, some spores are equipped with structures like wings or hydrophobic surfaces that aid in long-distance travel or attachment to surfaces. This combination of quantity and adaptability ensures that spores can colonize diverse habitats, from arid deserts to nutrient-poor soils.

Practical Implications: Harnessing Spore Resilience

Understanding spore survival mechanisms has practical applications in fields like agriculture, medicine, and astrobiology. For instance, spore-forming bacteria like *Bacillus thuringiensis* are used as bioinsecticides, their durability ensuring long-term efficacy in pest control. In medicine, spores of *Clostridium difficile* are targeted in hospital disinfection protocols due to their resistance to standard cleaning agents. Even in space exploration, spores are studied as potential candidates for panspermia, the hypothesis that life could spread between planets via meteorites. By mimicking spore adaptations, scientists are developing technologies for preserving vaccines, seeds, and even human cells in extreme conditions.

In essence, spores are not just alive when released—they are master survivors, equipped with a toolkit of structural, metabolic, and reparative strategies that defy environmental extremes. Their resilience offers both biological marvels and practical lessons for innovation across disciplines.

Are Spore-Based Probiotics Safe for Your Gut Health?

You may want to see also

Germination Triggers: What conditions activate spores to resume growth?

Spores, often likened to nature's survival capsules, remain dormant until specific environmental cues signal it's safe to emerge. These microscopic structures, produced by plants, fungi, and some bacteria, can endure extreme conditions—heat, cold, drought—for years, even centuries. But what precisely awakens them from this suspended state? Understanding the triggers that initiate germination is crucial, whether you're a gardener battling fungal pathogens or a scientist studying microbial resilience.

The Hydration Imperative

Water is the universal key that unlocks spore dormancy. For most species, absorption of a critical volume of water—typically 50–70% of the spore’s dry weight—initiates metabolic activity. This process, termed imbibition, reactivates enzymes and repairs cellular damage accumulated during dormancy. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores require at least 30 minutes of hydration before DNA repair mechanisms engage. However, water alone isn’t enough; it must be paired with other factors to sustain growth. Gardeners should note: Overwatering soil can create a humid environment conducive to fungal spore germination, making moisture management critical in disease prevention.

Temperature Thresholds and Timing

Spores are temperature-sensitive, with optimal ranges varying by species. Fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* germinate efficiently between 25–30°C, while bacterial spores such as *Clostridium botulinum* prefer 30–40°C. Cold-tolerant species, like certain Antarctic fungi, activate at temperatures as low as 4°C. Time at these temperatures matters too; *Alternaria* spores, for instance, require 6–8 hours at 20°C to initiate germination. For practical application, seed banks store spores at -20°C to halt metabolic activity, while food preservation methods often use heat (above 70°C) to destroy spore viability.

Nutrient Availability: The Growth Catalyst

While water and warmth awaken spores, nutrients fuel their transition to active life. Fungal spores, for example, detect amino acids, sugars, and inorganic salts in their environment, with glucose often acting as a primary stimulant. Bacterial spores may require specific germinants—molecules like L-alanine or calcium dipicolinate—to trigger emergence. In agriculture, this knowledge is leveraged to suppress pathogens; crop rotation disrupts nutrient availability, starving spores of the resources needed to germinate. Conversely, compost piles, rich in organic matter, become hotspots for spore activation, underscoring the dual-edged role of nutrients in ecosystems.

Light and pH: Subtle Yet Significant

Less obvious triggers include light and pH. Some fungal spores, such as those of *Neurospora crassa*, germinate faster under blue light, which mimics dawn conditions. pH shifts also play a role; *Penicillium* spores prefer slightly acidic environments (pH 5–6), while *Bacillus* spores tolerate a broader range (pH 6–9). Home fermenters should monitor pH levels, as deviations can inadvertently activate unwanted spores, spoiling batches. Similarly, greenhouse growers use pH-adjusted irrigation to deter fungal pathogens. These subtle factors remind us that spore germination is a finely tuned response to environmental nuance.

Mechanical Disruption: The Physical Nudge

In some cases, physical disturbance acts as a germination cue. Soil tillage, for instance, exposes buried spores to oxygen and nutrients, prompting activation. This phenomenon explains why newly disturbed soil often experiences a flush of fungal growth. Even air movement can trigger germination; wind-dispersed spores of *Cladosporium* may activate upon landing on a moist surface after travel. For homeowners, this means raking leaves or aerating lawns can inadvertently awaken dormant pathogens, highlighting the need for strategic timing in garden maintenance.

Spores’ ability to sense and respond to these triggers underscores their evolutionary brilliance. By manipulating these conditions—whether in a lab, garden, or kitchen—we can either harness their potential or halt their proliferation, turning the invisible world of spore biology into a tangible tool for control and creation.

Are Pterophyta Spores Safeguarded? Exploring Their Protective Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Viability Testing: Methods to determine if released spores are alive

Spores, by their nature, are resilient structures designed for survival in harsh conditions. However, determining whether released spores are alive requires precise viability testing methods. These tests are crucial in fields like agriculture, biotechnology, and environmental science, where spore functionality directly impacts outcomes. Below are key methods and considerations for assessing spore viability.

Direct Viability Assays: Staining Techniques and Germination Tests

One of the most straightforward methods is the use of vital stains, such as tetrazolium salts or fluorescein diacetate, which differentiate live spores from dead ones based on metabolic activity. For example, 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) reduces to a red formazan compound in living spores, providing a visual indicator of viability. Alternatively, germination tests involve placing spores in nutrient-rich conditions and monitoring for signs of growth, such as the emergence of hyphae or protoplasts. This method is particularly useful for fungi and bacteria but requires 24–48 hours for accurate results. A cautionary note: environmental factors like temperature and humidity can skew germination rates, so controlled conditions are essential.

Indirect Viability Assays: Flow Cytometry and PCR-Based Methods

For a more quantitative approach, flow cytometry measures spore membrane integrity and metabolic activity using fluorescent dyes. Propidium iodide, for instance, penetrates damaged membranes, staining DNA in non-viable spores. This technique offers high-throughput analysis, making it ideal for large-scale studies. PCR-based methods, such as reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR), detect mRNA transcripts associated with spore activation, providing molecular evidence of viability. However, these methods require specialized equipment and expertise, limiting their accessibility for field applications.

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

While direct assays like staining and germination tests are cost-effective and easy to implement, they may not detect spores in a dormant but viable state. Indirect methods, though more precise, are resource-intensive and may yield false negatives if spores are metabolically inactive. For instance, a study comparing TTC staining and flow cytometry found that the latter identified 15% more viable spores in a contaminated soil sample, highlighting the importance of method selection based on the research question.

Practical Tips for Accurate Testing

To ensure reliable results, standardize spore concentration to 10^6 spores/mL for consistency across tests. Maintain a controlled environment (e.g., 25°C and 60% humidity) during germination assays to minimize variability. When using molecular methods, include positive and negative controls to validate findings. For field-collected samples, pre-treat spores with a 0.1% Tween 20 solution to remove debris without compromising viability. Finally, replicate tests at least three times to account for biological variability and improve statistical confidence.

By combining these methods and adhering to best practices, researchers can accurately determine spore viability, ensuring the success of applications ranging from crop protection to microbial remediation.

Can Fungi Reproduce Without Spores? Exploring Alternative Reproduction Methods

You may want to see also

Life Cycle Role: How do spores contribute to organism survival post-release?

Spores, upon release, are not alive in the conventional sense but rather exist in a dormant, metabolically inactive state. This quiescent condition is a strategic adaptation, allowing them to endure harsh environmental conditions such as extreme temperatures, desiccation, and nutrient scarcity. By suspending metabolic processes, spores minimize energy expenditure, ensuring survival until conditions become favorable for growth. This dormancy is not a passive state but a highly regulated phase, with spores possessing the genetic machinery to sense environmental cues and activate when resources are available.

Consider the life cycle of *Bacillus subtilis*, a soil bacterium that forms endospores. When nutrients deplete, the bacterium initiates sporulation, encapsulating its DNA within a protective spore coat. These spores can persist for decades, withstanding UV radiation, heat, and chemicals. Upon encountering water and nutrients, the spore germinates, reactivating metabolic processes and resuming vegetative growth. This mechanism ensures the organism’s survival across generations, even in environments where active life would be unsustainable.

From a practical standpoint, understanding spore behavior is critical in fields like food safety and medicine. For instance, *Clostridium botulinum* spores, found in soil and food, can survive boiling temperatures (100°C) for hours. In food processing, this necessitates specific protocols such as pressure cooking at 121°C for 3 minutes to ensure spore destruction. Similarly, in healthcare, spore-forming pathogens like *Clostridioides difficile* require targeted disinfection strategies, as standard alcohol-based sanitizers are ineffective against spores.

Comparatively, fungal spores, such as those of *Aspergillus* or *Penicillium*, play a dual role in survival and dispersal. Unlike bacterial spores, fungal spores are often metabolically active to some degree, enabling them to germinate rapidly upon landing in a suitable environment. This adaptability allows fungi to colonize diverse habitats, from decaying organic matter to human lungs, as seen in aspergillosis infections. Fungal spores also contribute to ecosystem nutrient cycling, breaking down complex materials into simpler forms.

In summary, spores are not alive in the traditional sense post-release, but their dormant state is a masterclass in survival strategy. By halting metabolic activity and fortifying their structure, spores ensure organism persistence through adverse conditions. Whether bacterial or fungal, spores are not merely passive entities but dynamic agents equipped to sense, respond, and thrive when opportunity arises. This resilience underscores their critical role in both natural ecosystems and human-impacted environments, making them a fascinating subject for study and application.

Understanding Mold Spores: Causes, Health Risks, and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, spores are alive when released. They are dormant, unicellular, or multicellular structures that can survive harsh conditions and resume growth when favorable conditions return.

Spores have minimal metabolic activity when released. They enter a dormant state to conserve energy, but they remain viable and capable of reviving under suitable conditions.

No, spores cannot reproduce or grow immediately after release. They require specific environmental triggers, such as moisture, warmth, or nutrients, to activate and begin growth.

Yes, spores are considered living organisms even in their dormant state. They retain the ability to metabolize at a very low rate and can revive when conditions improve.

Spores can remain alive for extended periods, ranging from months to centuries, depending on the species and environmental conditions. Their durability is a key survival strategy.