Tetanus, caused by the bacterium *Clostridium tetani*, is a serious and potentially fatal disease characterized by muscle stiffness and spasms. The bacteria produce spores that are highly resilient and can survive in various environments, including soil, dust, and animal feces. A common question arises regarding whether these spores can survive in a wound that has bled. When a wound bleeds, it creates an environment that is initially aerobic, which is not ideal for *C. tetani* spores to germinate, as they thrive in anaerobic (oxygen-depleted) conditions. However, if the wound is deep, dirty, or contains necrotic tissue, it can quickly become anaerobic, providing a suitable environment for spore germination. Additionally, bleeding does not necessarily eliminate the risk of tetanus, as spores can still persist in the wound if they were present at the time of injury. Proper wound care, including thorough cleaning and, if necessary, tetanus vaccination or booster, is crucial to prevent infection.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Survival in Bleeding Wounds | Tetanus spores can survive in bleeding wounds if conditions are anaerobic. |

| Oxygen Requirement | Tetanus spores thrive in low-oxygen (anaerobic) environments. |

| Wound Conditions Favoring Survival | Deep puncture wounds, crush injuries, or wounds with necrotic tissue. |

| Bleeding Impact | Bleeding may temporarily introduce oxygen, but spores can persist if oxygen is depleted later. |

| Spore Resistance | Tetanus spores are highly resistant to heat, drying, and chemicals. |

| Germination Trigger | Spores germinate into active bacteria in anaerobic, nutrient-rich environments. |

| Toxin Production | Active bacteria produce tetanus toxin in anaerobic conditions. |

| Prevention | Proper wound cleaning, vaccination, and prompt medical care reduce risk. |

| Treatment | Antitoxin administration, wound debridement, and antibiotics if infected. |

| Common Misconception | Bleeding does not guarantee spore elimination; anaerobic conditions still allow survival. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Tetanus spore resistance to bleeding

Tetanus spores, produced by the bacterium *Clostridium tetani*, are remarkably resilient in harsh environments. Unlike many pathogens, they thrive in anaerobic (oxygen-depraved) conditions, which makes deep puncture wounds—like those from nails, needles, or animal bites—ideal breeding grounds. Bleeding, however, introduces oxygen into the wound, creating an environment theoretically hostile to these spores. Yet, their resistance to oxygen is not absolute; it’s their ability to persist in trace amounts and reactivate under favorable conditions that poses the real threat.

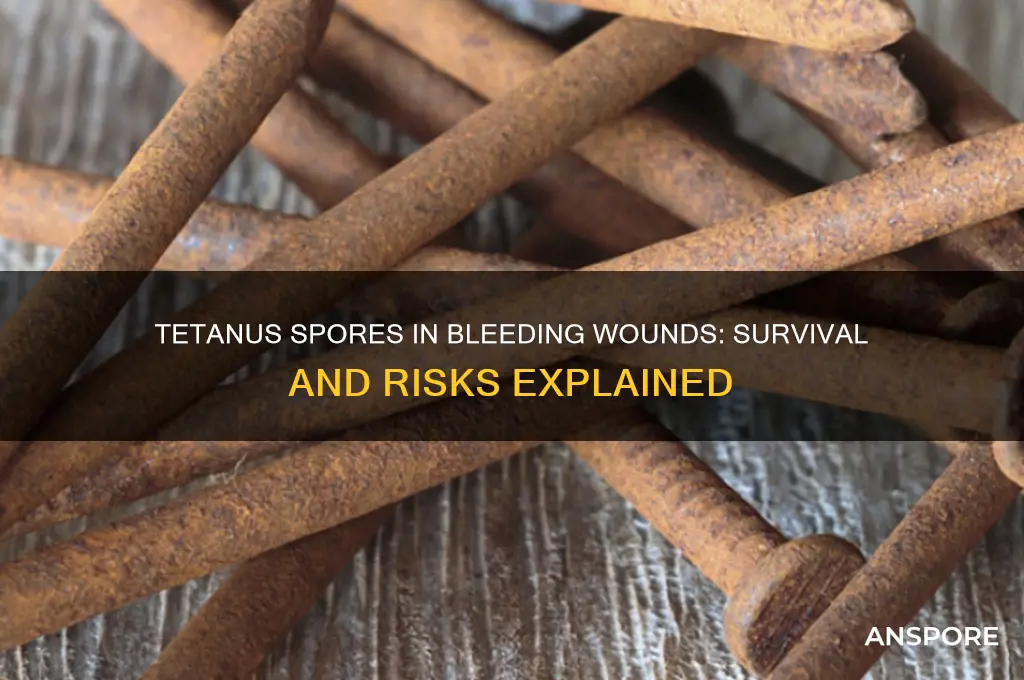

Consider a scenario: a gardener steps on a rusty nail, causing a deep puncture wound that bleeds. Despite the oxygen exposure from bleeding, tetanus spores can survive in the deeper, necrotic tissue where oxygen levels remain low. This is because bleeding does not uniformly oxygenate the entire wound site. The spores’ protective outer layer allows them to endure transient oxygen exposure, waiting for conditions to shift back in their favor. Thus, even a bleeding wound is not a guaranteed safeguard against tetanus.

To minimize risk, immediate wound care is critical. Clean the wound thoroughly with soap and water, removing all foreign debris. For deep or dirty wounds, seek medical attention promptly. A tetanus booster shot is recommended if your last dose was more than 5 years ago, especially for high-risk injuries. For adults, the Tdap vaccine (which also protects against pertussis) is typically administered, while children follow a scheduled series starting at 2 months of age.

Comparatively, other pathogens like *Staphylococcus* or *Streptococcus* are less likely to survive in oxygen-rich environments, making bleeding a more effective defense against them. Tetanus spores, however, are an outlier. Their resistance to oxygen, combined with their ability to produce potent neurotoxins, underscores why even a seemingly minor bleeding wound warrants attention. Prevention through vaccination and proper wound care remains the most effective strategy.

In summary, while bleeding introduces oxygen that can inhibit tetanus spore activation, it does not guarantee their eradication. The spores’ resilience in low-oxygen pockets within wounds highlights the importance of proactive measures. Vaccination, prompt wound cleaning, and medical evaluation for high-risk injuries are essential steps to prevent tetanus, even in wounds that bleed.

Are Psilocybe Spores Legal? Exploring the Legal Landscape and Implications

You may want to see also

Blood's role in spore survival

Tetanus spores thrive in environments devoid of oxygen, a condition known as anaerobiosis. When a wound bleeds, it introduces oxygen into the environment, which can be detrimental to spore survival. However, the role of blood in spore survival is not as straightforward as one might think. While oxygen is toxic to tetanus spores, blood also contains nutrients and growth factors that can potentially support spore germination and bacterial growth. This paradoxical effect highlights the complexity of wound environments and the need for a nuanced understanding of blood's role in spore survival.

Consider the following scenario: a puncture wound, such as a nail or splinter injury, is more likely to become infected with tetanus because it creates a deep, narrow channel that limits oxygen penetration. In this case, the presence of blood may actually facilitate spore survival by providing a nutrient-rich environment. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), puncture wounds account for approximately 20-30% of tetanus cases in the United States. To minimize the risk of infection, it is essential to clean the wound thoroughly with soap and water, removing any foreign debris, and seeking medical attention if the wound is deep or dirty. A healthcare professional may recommend a tetanus booster shot, typically containing 0.5 mL of tetanus toxoid, to individuals who have not been vaccinated or are unsure of their vaccination status.

In contrast, a wound that bleeds profusely may create an environment that is less conducive to spore survival due to the increased oxygen tension. However, this does not mean that tetanus infection is impossible in such cases. The amount of blood loss, the depth of the wound, and the individual's immune status all play a role in determining the risk of infection. For instance, a study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases found that individuals with compromised immune systems, such as those with diabetes or HIV, are at a higher risk of developing tetanus even from minor wounds. To reduce the risk of infection, individuals with chronic conditions should take extra precautions when handling sharp objects or engaging in activities that may result in injury.

The interplay between blood and spore survival has significant implications for wound management and infection prevention. Healthcare professionals should consider the following practical tips when treating wounds: (1) irrigate the wound with sterile saline solution to remove debris and reduce bacterial load; (2) administer a tetanus booster shot if necessary, following the recommended dosage and schedule; (3) monitor the wound for signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, or discharge; and (4) educate patients on proper wound care, including keeping the area clean and dry. By understanding the complex role of blood in spore survival, healthcare providers can develop more effective strategies for preventing tetanus infection and improving patient outcomes. Ultimately, a comprehensive approach to wound management that takes into account the unique characteristics of each wound and patient is essential for minimizing the risk of tetanus and other infectious complications.

A comparative analysis of wound types and their associated risks can further illustrate the importance of blood's role in spore survival. For example, a clean, superficial wound with minimal bleeding is less likely to support spore germination compared to a deep, punctate wound with limited oxygen exposure. Similarly, a wound in a vaccinated individual is less susceptible to tetanus infection due to the presence of protective antibodies. By recognizing these differences and tailoring wound management strategies accordingly, healthcare providers can optimize patient care and reduce the burden of tetanus infection. This may involve implementing targeted vaccination campaigns, improving wound care protocols, and increasing public awareness about the risks associated with certain types of injuries. As our understanding of blood's role in spore survival continues to evolve, so too will our ability to prevent and manage tetanus infection in diverse patient populations.

Hydrogen Peroxide's Power: Can It Effectively Kill Mold Spores?

You may want to see also

Wound conditions favoring spores

Tetanus spores thrive in environments devoid of oxygen, making deep puncture wounds particularly hospitable. When a wound bleeds, it introduces oxygen, which might seem counterintuitive to spore survival. However, the bleeding itself doesn’t guarantee spore eradication. If the wound is deep and narrow—like those from nails, needles, or animal bites—blood flow may not penetrate the entire wound cavity. This creates anaerobic pockets where spores can germinate and produce tetanus toxin, the culprit behind the disease’s severe symptoms.

Consider the mechanics of a puncture wound: the surrounding tissue compresses, limiting oxygen penetration even if bleeding occurs. For instance, a rusty nail wound, a classic tetanus risk scenario, often creates a sealed environment ideal for spore activation. While rust itself doesn’t cause tetanus, it indicates the presence of iron oxide, which can harbor soil-borne spores. If such a wound bleeds minimally or superficially, the internal environment remains anaerobic, allowing spores to persist and multiply.

To mitigate risk, proper wound care is critical. Clean the wound thoroughly with soap and water, removing all debris. For deep or dirty wounds, seek medical attention immediately. A healthcare provider may recommend a tetanus booster if your last dose was over 5 years ago, especially for high-risk injuries. Irrigation with sterile saline or a 0.05% povidone-iodine solution can further reduce spore burden. Remember, bleeding alone isn’t a safeguard—it’s the wound’s depth, cleanliness, and oxygen exposure that determine spore survival.

Comparatively, superficial wounds that bleed profusely are less likely to support spore growth due to increased oxygen exposure. However, don’t rely on bleeding as a protective mechanism. Even minor wounds in contaminated environments, like gardening injuries or animal scratches, can introduce spores. Always assess the wound’s depth, location, and potential exposure to soil or manure. Proactive measures, such as staying up-to-date on tetanus vaccinations and promptly treating injuries, are far more effective than assuming bleeding will neutralize the threat.

In summary, wound conditions favoring tetanus spores include depth, lack of oxygen, and contamination with soil or organic matter. Bleeding may occur but doesn’t ensure spore elimination, especially in puncture wounds. Prioritize thorough cleaning, professional evaluation, and vaccination to prevent tetanus. Understanding these conditions empowers you to act swiftly, reducing the risk of this potentially fatal disease.

Heat-Resistant Bacterial Spores: The Scientist Behind the Discovery

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Immune response to spores in wounds

Tetanus spores, known for their resilience, can indeed survive in wounds, even those that have bled. Bleeding itself does not eliminate these spores, as they are highly resistant to harsh conditions, including exposure to oxygen and blood components. The immune system’s response to these spores in a wound is critical in determining whether infection develops. When tetanus spores germinate into active bacteria, they produce tetanospasmin, a potent neurotoxin that interferes with nerve signaling, leading to muscle stiffness and spasms. The immune response, therefore, must act swiftly to neutralize both the bacteria and the toxin.

Upon entry into a wound, tetanus spores encounter the innate immune system, the body’s first line of defense. Neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells are recruited to the site to engulf and destroy the spores or bacteria. However, tetanus spores are encased in a protective outer layer, making them difficult for immune cells to penetrate. If the immune response is insufficient, the spores germinate and multiply, releasing tetanospasmin into the surrounding tissue. This toxin binds to nerve endings, blocking the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters, which results in uncontrolled muscle contractions.

The adaptive immune response, involving B and T cells, plays a secondary role in combating tetanus. B cells produce antibodies that neutralize tetanospasmin, preventing it from causing further damage. However, this response takes days to develop, and by then, the toxin may have already caused severe symptoms. Vaccination, such as the tetanus toxoid vaccine, primes the immune system by generating memory B cells that can rapidly produce antibodies upon exposure to the toxin. A single dose of tetanus toxoid provides protection for 10 years, while booster shots every 5–10 years maintain immunity in adults.

Practical measures to support the immune response in wound care include thorough cleaning with soap and water, followed by the application of antiseptic solutions like hydrogen peroxide or iodine. Deep or puncture wounds, especially those contaminated with soil or feces, require immediate medical attention. Healthcare providers may administer tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG), which contains preformed antibodies to neutralize the toxin, alongside a booster vaccine. This dual approach ensures both immediate and long-term protection, particularly in individuals with uncertain vaccination histories or high-risk wounds.

In summary, the immune response to tetanus spores in wounds is a race against time. While the innate immune system attempts to contain the spores, the adaptive response, bolstered by vaccination, is crucial for neutralizing the toxin. Proactive wound care and timely medical intervention are essential to prevent tetanus infection, highlighting the interplay between immune function and clinical management.

Are Spores on Potatoes Safe? A Guide to Edible Potatoes

You may want to see also

Effect of bleeding on spore germination

Bleeding at a wound site significantly influences the environment in which tetanus spores reside, potentially altering their ability to germinate. Tetanus spores, produced by *Clostridium tetani*, are remarkably resilient, capable of surviving in soil and other environments for years. However, germination—the process by which spores transform into active, toxin-producing bacteria—requires specific conditions, including anaerobiosis (absence of oxygen) and nutrients. When a wound bleeds, it introduces oxygen into the environment, creating an aerobic atmosphere that is generally inhibitory to *C. tetani*. This oxygen influx can temporarily suppress spore germination, as these organisms thrive in low-oxygen conditions.

Consider the mechanics of a bleeding wound: as blood flows, it not only oxygenates the area but also flushes out debris and potential nutrients that spores might utilize. This dual action—oxygenation and cleansing—creates a less favorable environment for spore activation. However, the effect is not absolute. If the wound is deep, necrotic, or contains devitalized tissue, pockets of anaerobiosis may persist despite bleeding. In such cases, spores could still find localized conditions suitable for germination, particularly if the bleeding is minimal or ceases quickly.

From a practical standpoint, managing a bleeding wound to prevent tetanus involves more than just stopping the blood flow. Thoroughly cleaning the wound with soap and water or a sterile saline solution is critical, as it removes spores and reduces the risk of contamination. For high-risk wounds—such as puncture wounds, crush injuries, or those involving soil or manure—a tetanus booster shot is recommended if more than 5 years have passed since the last dose. This proactive approach ensures that even if spores do germinate, the body is equipped to neutralize the toxin before it causes systemic harm.

Comparatively, non-bleeding wounds, such as puncture wounds or those covered by foreign bodies, pose a higher risk for tetanus because they provide the anaerobic conditions spores require. Bleeding, while not a foolproof safeguard, introduces factors that can delay or inhibit spore germination. However, reliance on bleeding alone is insufficient for prevention. Combining immediate wound care with vaccination remains the most effective strategy to mitigate tetanus risk, regardless of whether the wound bled.

Are Spore Mods Still Supported? Exploring Active Community Creations

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, tetanus spores can survive in a wound that has bled, especially if the wound is deep, dirty, or lacks adequate oxygen supply, as these conditions are favorable for spore activation and bacterial growth.

Bleeding does not necessarily prevent tetanus spores from growing. While blood can introduce oxygen, which tetanus bacteria typically avoid, deep or necrotic wounds may still provide an anaerobic environment suitable for spore activation.

Tetanus spores can remain dormant in a wound for an extended period, sometimes weeks or even months, until conditions become favorable for them to germinate and produce the toxin that causes tetanus.

Properly cleaning a bleeding wound can reduce the risk of tetanus by removing dirt and debris, but it may not eliminate all spores. Tetanus spores are highly resilient and can survive in harsh conditions.

Yes, if your bleeding wound was exposed to soil, rust, or other potentially contaminated materials, it’s advisable to get a tetanus shot, especially if your last vaccination was more than 5–10 years ago, to prevent infection.