Flowers, the reproductive structures of angiosperms, are primarily known for producing seeds through sexual reproduction involving pollen and ovules. However, the question of whether flowers release haploid, wind-blown spores is rooted in a misunderstanding of plant biology. Haploid spores are characteristic of non-seed plants like ferns and mosses, which reproduce via alternation of generations and release spores for dispersal. In contrast, flowering plants (angiosperms) do not produce spores; instead, they generate pollen grains, which are also haploid but function as male gametophytes in the fertilization process. Pollen is indeed often wind-dispersed in some species, but it is not a spore. Thus, while flowers facilitate pollination and seed production, they do not release haploid, wind-blown spores, as this mechanism is exclusive to spore-producing plants.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Do flowers release haploid wind-blown spores? | No |

| Reason | Flowers are reproductive structures of angiosperms (flowering plants) and produce seeds, not spores. |

| Reproductive method of flowers | Sexual reproduction via pollination (transfer of pollen from anther to stigma) |

| Type of gametes produced by flowers | Diploid (2n) gametes (egg and sperm) |

| Plants that release haploid wind-blown spores | Ferns, mosses, fungi, and some non-flowering plants (e.g., conifers release pollen grains, which are haploid microspores) |

| Structure responsible for spore production in spore-releasing plants | Sporangia (in ferns, mosses) or sporangiophores (in fungi) |

| Type of spores released by spore-releasing plants | Haploid (n) spores (e.g., fern spores, fungal spores) |

| Dispersal method of spores | Wind, water, or animals (depending on the plant species) |

| Role of spores in plant life cycle | Develop into gametophytes, which produce gametes for sexual reproduction |

| Comparison with flower reproduction | Flowers rely on seeds for dispersal and development into new plants, whereas spores develop into gametophytes. |

Explore related products

$13.29 $22.99

What You'll Learn

- Sporangia Structure: Haploid spores develop in sporangia, specialized structures within flower-like parts of certain plants

- Wind Dispersal Mechanism: Spores are lightweight, enabling wind to carry them over long distances for pollination

- Alternation of Generations: Spores represent the haploid phase, alternating with the diploid plant generation

- Non-Flowering Plants: Ferns, mosses, and fungi release spores, not flowers, which are angiosperm-specific

- Misconception Clarification: Flowers produce pollen (haploid) but not spores; spores are from sporophytes in lower plants

Sporangia Structure: Haploid spores develop in sporangia, specialized structures within flower-like parts of certain plants

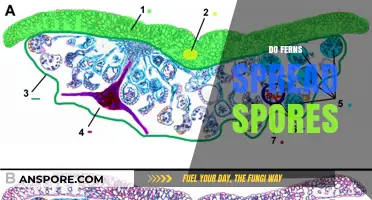

Flowers, as we commonly know them, do not release haploid wind-blown spores. This reproductive strategy is more characteristic of non-flowering plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi. However, the concept of sporangia—specialized structures where haploid spores develop—is crucial to understanding the reproductive mechanisms of these organisms. Sporangia are typically found in the flower-like parts of certain plants, such as the fronds of ferns or the capsules of mosses, where they produce and disperse spores to ensure the next generation.

Analytically, sporangia are marvels of evolutionary adaptation. Their structure is optimized for spore production and dispersal. For instance, in ferns, sporangia are clustered into structures called sori, often located on the undersides of leaves. Each sporangium contains hundreds of haploid spores, which are released through a precise mechanism involving dehydration and the buildup of internal pressure. This design ensures that spores are ejected efficiently, often carried by wind to new locations, maximizing the plant’s reproductive reach.

Instructively, observing sporangia in action can be a fascinating educational activity. To witness this process, collect a mature fern frond with visible sori. Place it in a dry, warm environment for a few hours to encourage spore release. Then, carefully shake the frond over a white piece of paper. The spores, often brown or black, will scatter, forming a visible pattern. This simple experiment demonstrates the sporangia’s role in spore dispersal and highlights the adaptability of non-flowering plants.

Comparatively, while flowers rely on seeds for reproduction, sporangia-bearing plants use spores, which are lighter and more numerous. This difference reflects distinct evolutionary strategies: seeds require pollination and fertilization, whereas spores can develop into new individuals independently. However, both systems share a common goal—ensuring genetic diversity and survival. For gardeners or botanists, understanding these mechanisms can inform cultivation practices, such as creating spore-friendly environments for ferns or protecting flowering plants from pollinators.

Descriptively, sporangia are not just functional but also aesthetically intriguing. Under a microscope, their walls reveal intricate layers of cells, each contributing to spore development and release. In mosses, the sporangium, or capsule, is often perched atop a slender stalk, resembling a miniature lantern. This structure not only protects the spores but also aids in their dispersal, as the capsule dries and splits open, releasing its contents to the wind. Such details underscore the elegance of nature’s design, blending utility with beauty.

Practically, knowing about sporangia can aid in plant care and conservation. For example, if cultivating ferns indoors, ensure they receive adequate humidity to mimic their natural habitat, which supports sporangia function. Additionally, understanding spore dispersal can help in propagating rare plant species. By collecting spores and sowing them in controlled environments, enthusiasts can contribute to biodiversity preservation. This knowledge bridges the gap between scientific curiosity and actionable gardening techniques, making sporangia a vital topic for both botanists and hobbyists alike.

Can You See Rhizopus Spores on a Microscope Slide?

You may want to see also

Wind Dispersal Mechanism: Spores are lightweight, enabling wind to carry them over long distances for pollination

Spores, by their very nature, are designed for dispersal. Their lightweight structure, often just a single cell, allows them to be easily carried by the slightest breeze. This wind dispersal mechanism is a key strategy for plants that rely on spores for reproduction, particularly ferns, mosses, and fungi. Unlike seeds, which are typically heavier and require animals or water for transport, spores can travel vast distances, increasing the chances of finding suitable habitats for growth.

Consider the lifecycle of a fern. After a fern plant matures, it produces spore cases called sporangia on the underside of its fronds. When these sporangia burst, they release thousands of microscopic spores into the air. Each spore is so light—typically weighing less than a milligram—that even a gentle wind can carry it for miles. This long-distance travel is crucial for ferns, which often grow in shaded, isolated areas where direct contact with other plants is limited. For example, a single fern spore has been recorded traveling over 30 kilometers in optimal wind conditions, demonstrating the efficiency of this dispersal method.

The effectiveness of wind dispersal lies in its unpredictability and reach. While animals and water currents can transport seeds in specific directions, wind is omnidirectional, scattering spores in all directions. This randomness increases the likelihood that at least some spores will land in environments conducive to germination. However, this method is not without its drawbacks. Because wind dispersal is passive, many spores may land in unsuitable locations, such as dry soil or areas with insufficient light. To compensate, spore-producing plants often release enormous quantities—a single fern plant can produce millions of spores annually—to ensure that a few will successfully grow into new plants.

Practical observations of wind-dispersed spores can be seen in everyday life. For instance, the dusty coating on car windshields in spring is often composed of pine pollen, a type of spore. Similarly, the green film on ponds in early summer is frequently caused by algal spores carried by the wind. To study this phenomenon, one can conduct a simple experiment: place a clean, white surface outdoors for a few hours and examine it under a magnifying glass. The speckles of dust will likely include spores, identifiable by their uniform size and shape. This activity not only illustrates the prevalence of wind-dispersed spores but also highlights their role in shaping ecosystems.

In conclusion, the wind dispersal mechanism of spores is a testament to nature’s ingenuity. By leveraging the lightest of structures and the most ubiquitous of forces—wind—plants ensure their reproductive success across vast distances. While this method is inefficient in terms of individual spore survival, its scale and randomness make it a highly effective strategy for colonizing new territories. Understanding this process not only deepens our appreciation for plant biology but also offers insights into how we might design more efficient dispersal systems for seeds in agriculture or conservation efforts.

Breathing in Spores: Unraveling Dizziness, Nausea, and Breathing Difficulties

You may want to see also

Alternation of Generations: Spores represent the haploid phase, alternating with the diploid plant generation

Flowers, as we commonly know them, do not release haploid wind-blown spores. Instead, this process is characteristic of non-flowering plants like ferns, mosses, and certain algae, which exhibit a fascinating life cycle known as alternation of generations. In this cycle, the haploid phase, represented by spores, alternates with the diploid phase, represented by the mature plant. Understanding this mechanism sheds light on the diversity of plant reproduction strategies and highlights the evolutionary divergence between flowering and non-flowering plants.

Consider the life cycle of a fern as a prime example. It begins with a haploid spore germinating into a small, heart-shaped structure called a prothallus. This prothallus is the gametophyte generation, producing both sperm and eggs. Upon fertilization, the diploid sporophyte generation develops, eventually growing into the familiar fern plant we recognize. Crucially, this mature fern does not flower; instead, it releases spores from the undersides of its fronds, perpetuating the cycle. This alternation ensures genetic diversity and adaptability, as the haploid phase is more vulnerable to environmental changes but allows for rapid evolution.

In contrast, flowering plants (angiosperms) bypass the spore-producing phase entirely. Their life cycle is dominated by the diploid generation, with flowers serving as reproductive structures that produce seeds. While pollen grains in angiosperms are haploid, they are not spores; they are male gametophytes directly involved in fertilization. This distinction underscores the evolutionary innovation of flowering plants, which have streamlined their reproductive process to enhance efficiency and success in diverse ecosystems.

For gardeners or botanists studying plant reproduction, recognizing these differences is essential. If you’re cultivating ferns or mosses, ensure their environment supports spore dispersal—adequate airflow and humidity are critical. Conversely, when growing flowering plants, focus on pollination and seed development, as these are the primary reproductive mechanisms. Practical tips include using fans to mimic wind for spore-bearing plants or hand-pollinating flowers in controlled environments to ensure successful seed production.

In essence, alternation of generations is a testament to the adaptability of plant life. While flowers do not release haploid wind-blown spores, this process remains a cornerstone of non-flowering plant reproduction. By studying these contrasting strategies, we gain deeper insight into the intricate ways plants ensure their survival and propagation across generations. Whether you’re a hobbyist or a professional, understanding these nuances enriches your appreciation of the natural world and enhances your ability to nurture diverse plant species effectively.

Can Mold Spores Survive on Metal Surfaces? Facts and Insights

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Non-Flowering Plants: Ferns, mosses, and fungi release spores, not flowers, which are angiosperm-specific

Ferns, mosses, and fungi are often overshadowed by their flowering counterparts, yet they play a crucial role in ecosystems worldwide. Unlike angiosperms, which produce flowers and seeds, these non-flowering plants rely on spores for reproduction. Spores are lightweight, single-celled structures that can be dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing these plants to colonize diverse environments. For instance, a single fern can release millions of spores in a season, ensuring at least a few land in suitable conditions to grow. This method of reproduction is not only efficient but also highlights the adaptability of non-flowering plants in the absence of complex floral structures.

To understand the spore-release process, consider the life cycle of a fern. It begins with a sporophyte, the mature plant we commonly recognize, which produces spore cases called sporangia on the undersides of its fronds. When mature, these sporangia release haploid spores, each capable of developing into a gametophyte—a small, heart-shaped structure that grows in moist environments. The gametophyte then produces eggs and sperm, which, when fertilized, grow into a new sporophyte. This alternation of generations is a hallmark of ferns, mosses, and some fungi, contrasting sharply with the seed-based reproduction of flowering plants.

Mosses, another group of non-flowering plants, follow a similar spore-based reproductive strategy. They thrive in damp, shady areas and release spores from capsules atop slender stalks called setae. These spores are incredibly resilient, capable of surviving harsh conditions until they find a suitable substrate to germinate. For gardeners or enthusiasts looking to cultivate moss, maintaining consistent moisture and avoiding direct sunlight are key. A practical tip: collect moss from the wild responsibly, ensuring you leave enough to continue its natural growth, and use a blender to create a moss slurry that can be painted onto surfaces for even distribution.

Fungi, though often grouped with plants, are a distinct kingdom with their own spore-release mechanisms. Mushrooms, for example, produce spores in gills or pores beneath their caps. A single mushroom can release trillions of spores, which are carried by air currents to new locations. This prolific spore production is why fungi can quickly colonize areas after disturbances like wildfires or deforestation. For those interested in mushroom cultivation, controlling humidity and temperature is critical. A humidity level of 85-95% and a temperature range of 65-75°F (18-24°C) are ideal for most species during the fruiting stage.

In contrast to these non-flowering plants, angiosperms (flowering plants) have evolved a different reproductive strategy centered around flowers and seeds. Flowers attract pollinators, ensuring genetic diversity through cross-fertilization, while seeds provide protection and nutrients for the developing embryo. This complexity has made angiosperms the dominant plant group on Earth. However, the simplicity and efficiency of spore-based reproduction in ferns, mosses, and fungi remind us of the diversity of life’s strategies. By studying these non-flowering plants, we gain insights into the evolutionary pathways that have shaped the plant kingdom and the ecosystems they support.

Are Spores Genetically Identical? Exploring the Science Behind Spore Diversity

You may want to see also

Misconception Clarification: Flowers produce pollen (haploid) but not spores; spores are from sporophytes in lower plants

Flowers, with their vibrant colors and intricate structures, are often misunderstood in their reproductive roles. A common misconception is that flowers release haploid wind-blown spores, similar to how ferns or mosses reproduce. However, this is inaccurate. Flowers produce pollen, which is indeed haploid, but it is not a spore. Pollen grains are male gametophytes that serve to fertilize the female ovules within the flower, leading to seed production. Spores, on the other hand, are produced by sporophytes in lower plants like ferns and mosses, and they develop into new individuals through asexual reproduction. Understanding this distinction is crucial for appreciating the diversity of plant reproductive strategies.

To clarify further, let’s examine the life cycles of flowering plants (angiosperms) versus lower plants (e.g., ferns and mosses). In angiosperms, the dominant phase is the diploid sporophyte, which produces flowers. Within these flowers, microsporangia in the anthers generate pollen grains through meiosis, ensuring they are haploid. These pollen grains are then dispersed by wind, insects, or other means to reach the stigma of a compatible flower. In contrast, lower plants alternate between a diploid sporophyte and a haploid gametophyte phase. Spores are produced by the sporophyte and develop into gametophytes, which then produce gametes. This fundamental difference in life cycles explains why flowers do not release spores—their reproductive mechanism is entirely distinct.

From a practical standpoint, this clarification is essential for gardeners, botanists, and educators. For instance, if you’re teaching students about plant reproduction, emphasizing the difference between pollen and spores can prevent confusion. Gardeners should also understand that pollen dispersal is a key factor in plant breeding and hybridization, while spores are irrelevant in this context. A simple tip: observe the structures involved. Flowers have stamens (producing pollen) and pistils (receiving pollen), whereas sporophytes in ferns have sporangia that release spores. This visual distinction can reinforce the conceptual difference.

Persuasively, it’s worth noting that conflating pollen and spores undermines the remarkable complexity of plant evolution. Angiosperms, with their flowers and seeds, represent a highly advanced reproductive strategy that has allowed them to dominate terrestrial ecosystems. Lower plants, while less complex, showcase the foundational mechanisms of plant reproduction. By accurately distinguishing between pollen and spores, we honor the evolutionary ingenuity of both groups. This precision also fosters a deeper appreciation for the natural world, encouraging curiosity and respect for biodiversity.

In conclusion, while both pollen and spores are haploid and often wind-dispersed, their origins and functions are entirely different. Flowers produce pollen as part of sexual reproduction in angiosperms, whereas spores are produced by sporophytes in lower plants for asexual reproduction. Recognizing this distinction not only corrects a common misconception but also enriches our understanding of plant biology. Whether you’re a student, gardener, or nature enthusiast, this clarity empowers you to engage with plants more thoughtfully and accurately.

Exploring Spore Drives: Fact or Fiction in Modern Science?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, flowers do not release haploid wind-blown spores. Flowers are reproductive structures of angiosperms (flowering plants) and produce seeds, not spores.

Plants like ferns, mosses, and fungi release haploid wind-blown spores as part of their life cycle. These are non-flowering plants or organisms.

No, spores and pollen are different. Spores are haploid reproductive cells produced by plants like ferns and fungi, while pollen is produced by flowering plants (angiosperms) and gymnosperms (e.g., conifers) and is part of seed production.

No, flowering plants (angiosperms) do not produce spores. They reproduce via seeds, which develop from flowers after pollination.

Flowers reproduce through seeds. Pollen (male gametes) is transferred to the stigma, fertilizing the ovule, which develops into a seed. This process involves diploid cells, not haploid spores.