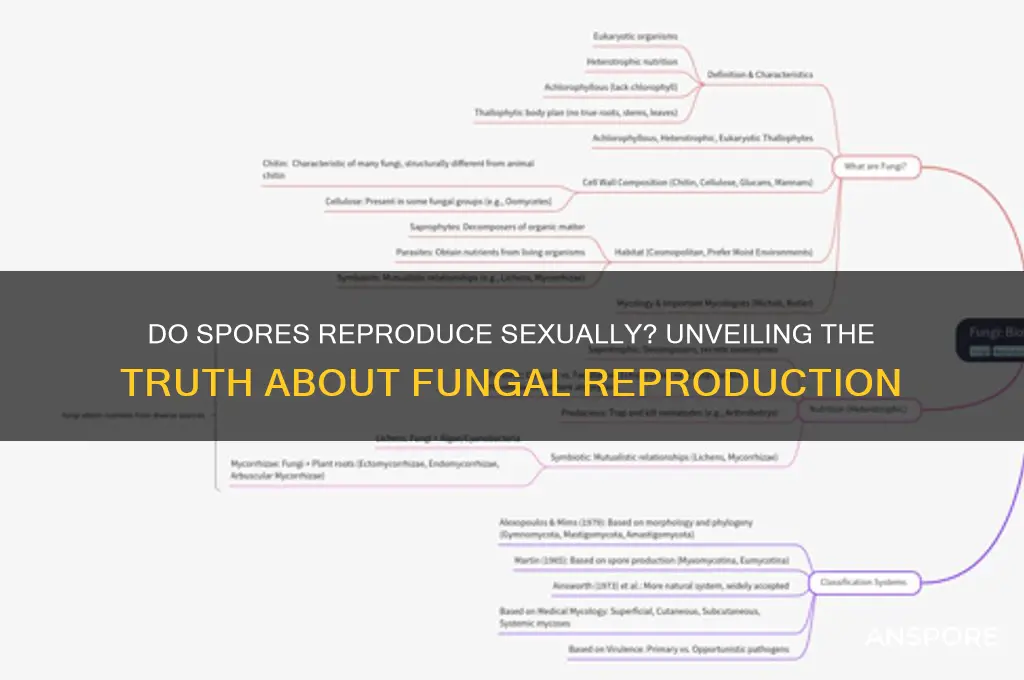

Spores, often associated with fungi, plants, and some bacteria, are primarily known for their role in asexual reproduction, where they develop into new individuals without the fusion of gametes. However, the question of whether spores can reproduce sexually is intriguing, as it delves into the complexity of reproductive strategies in various organisms. While many spores are indeed asexual, certain species, such as those in the fungal kingdom, exhibit a more nuanced approach. Some fungi produce spores through sexual reproduction, involving the fusion of haploid cells to form a diploid zygote, which then develops into a spore. This process, known as meiosis, ensures genetic diversity and adaptability in changing environments. Therefore, while not all spores reproduce sexually, specific types do, highlighting the diverse reproductive mechanisms in the natural world.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Type | Spores can reproduce both sexually and asexually, depending on the organism and environmental conditions. |

| Sexual Reproduction | Some fungi and plants (e.g., ferns, mosses) produce spores through sexual reproduction, involving the fusion of gametes (e.g., zygospores in fungi). |

| Asexual Reproduction | Many spores are produced asexually via processes like sporulation in bacteria, fungi, and plants (e.g., conidia, endospores). |

| Genetic Diversity | Sexual spores increase genetic diversity through meiosis and recombination, while asexual spores are genetically identical to the parent. |

| Function | Spores serve as dispersal and survival structures, enabling organisms to withstand harsh conditions (e.g., heat, drought). |

| Examples | Sexual spores: Fern spores, fungal zygospores; Asexual spores: Bacterial endospores, fungal conidia. |

| Environmental Trigger | Sexual spore production often occurs in response to specific environmental cues (e.g., nutrient depletion, stress). |

| Life Cycle Role | Spores are part of the alternation of generations in plants and the life cycle of fungi, bridging different stages of development. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Spores in Fungi: Most fungi alternate between sexual and asexual spore production for reproduction and survival

- Sexual Spores in Plants: Some plants, like ferns, produce sexual spores via gametophytes for reproduction

- Meiosis in Spore Formation: Sexual spores often result from meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring

- Zygospores in Fungi: Formed by fusion of gametes, zygospores are a sexual spore type in fungi

- Oospores in Algae: Sexual spores in algae, like oospores, develop from fertilized eggs for reproduction

Spores in Fungi: Most fungi alternate between sexual and asexual spore production for reproduction and survival

Fungi are masters of survival, and their reproductive strategies reflect this. Unlike plants and animals, most fungi don’t rely on a single method of reproduction. Instead, they alternate between sexual and asexual spore production, a duality that ensures their persistence in diverse and often harsh environments. This alternation of generations—a lifecycle phase involving both haploid and diploid forms—is a cornerstone of fungal biology. Sexual spores, such as zygospores or ascospores, arise from the fusion of gametes, promoting genetic diversity. Asexual spores, like conidia or sporangiospores, are produced without fertilization, allowing rapid colonization of favorable habitats. This dual approach maximizes adaptability, enabling fungi to thrive in niches ranging from forest floors to human lungs.

Consider the lifecycle of *Aspergillus fumigatus*, a common mold found in soil and indoor environments. When conditions are optimal, it produces asexual conidia, which disperse through the air and germinate quickly to establish new colonies. However, under stress—such as nutrient scarcity or temperature fluctuations—it shifts to sexual reproduction, forming cleistothecia containing genetically diverse ascospores. This flexibility ensures survival in unpredictable ecosystems. For instance, in a hospital setting, asexual spores can cause opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients, while sexual spores may lie dormant, waiting for the right conditions to emerge. Understanding this alternation is critical for managing fungal pathogens and harnessing fungi in biotechnology, such as in the production of antibiotics like penicillin.

From a practical standpoint, gardeners and farmers can leverage this knowledge to control fungal populations. For example, crop rotation disrupts the lifecycle of asexual spores by denying them a consistent host, while maintaining soil health promotes conditions favorable for sexual reproduction, which often reduces virulence. Similarly, in indoor environments, controlling humidity below 60% inhibits the germination of both asexual and sexual spores, reducing mold growth. For those working with fungi in labs, inducing sexual reproduction through stress factors like pH shifts or nutrient limitation can yield genetically diverse strains for research. These strategies highlight the importance of targeting both reproductive modes for effective fungal management.

Comparatively, the alternation of generations in fungi contrasts sharply with the reproductive strategies of bacteria, which rely primarily on asexual division, and plants, which often separate sexual and asexual phases spatially or temporally. Fungi’s ability to switch between modes within a single lifecycle provides a unique evolutionary advantage. For instance, while bacterial mutations are their primary source of genetic variation, fungi can generate diversity through sexual recombination, a process akin to shuffling a genetic deck. This makes fungi both resilient and dynamic, capable of evolving rapidly in response to environmental pressures, such as antifungal resistance in clinical settings.

In conclusion, the alternation between sexual and asexual spore production is not just a reproductive quirk but a survival mechanism finely tuned by millions of years of evolution. By understanding this duality, we can better manage fungi in agriculture, medicine, and industry. Whether combating pathogens or cultivating beneficial species, the key lies in recognizing and addressing both modes of reproduction. This knowledge transforms our approach from reactive to proactive, ensuring we work with, rather than against, the natural strategies of these remarkable organisms.

Playing Spore Without Origin: Requirements and Alternatives Explained

You may want to see also

Sexual Spores in Plants: Some plants, like ferns, produce sexual spores via gametophytes for reproduction

Ferns and other plants that produce sexual spores via gametophytes offer a fascinating glimpse into the diversity of plant reproduction. Unlike the asexual spores commonly associated with fungi and some plants, these sexual spores are the result of a complex, two-step process involving the gametophyte generation. This method ensures genetic diversity, a critical factor in the survival and adaptation of plant species. For instance, ferns release spores that develop into small, heart-shaped gametophytes, which then produce both male and female reproductive cells. This dual-stage lifecycle highlights the intricate balance between stability and variation in plant evolution.

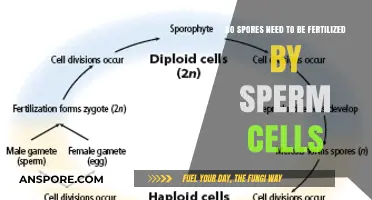

To understand the role of gametophytes in sexual spore production, consider the lifecycle of a fern. It begins with the sporophyte (the mature fern plant) releasing spores through structures called sporangia. These spores germinate into gametophytes, which are typically just a few millimeters in size. The gametophyte is a self-sustaining organism that produces gametes: sperm and eggs. When conditions are right, sperm swim to fertilize eggs, resulting in a new sporophyte. This process is not only a marvel of nature but also a practical example of how plants can thrive in diverse environments, from shady forests to rocky outcrops.

From a practical standpoint, gardeners and botanists can leverage this knowledge to cultivate ferns and other spore-producing plants more effectively. For example, maintaining high humidity and consistent moisture levels mimics the natural habitat where gametophytes thrive, increasing the chances of successful spore germination. Additionally, understanding the sexual nature of these spores can help in conservation efforts, as it underscores the importance of preserving genetic diversity within plant populations. By collecting and propagating spores from a variety of sources, enthusiasts can contribute to the resilience of these species.

Comparatively, the sexual spore production in plants like ferns contrasts sharply with the asexual methods seen in many fungi and algae. While asexual spores are efficient for rapid colonization, sexual spores offer long-term advantages by introducing genetic recombination. This distinction is crucial in agriculture and ecology, where the balance between uniformity and diversity directly impacts crop yields and ecosystem health. For instance, while asexual reproduction might be favored for monoculture crops, sexual reproduction in plants ensures adaptability to changing climates and diseases.

In conclusion, the production of sexual spores via gametophytes in plants like ferns is a testament to the ingenuity of nature. This process not only ensures genetic diversity but also provides practical insights for cultivation and conservation. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can better appreciate and protect the intricate lifecycles of these remarkable plants. Whether you're a gardener, scientist, or nature enthusiast, understanding sexual spores opens a window into the hidden complexities of the plant world.

Removing Drywall: Risks of Spreading Mold Spores and Prevention Tips

You may want to see also

Meiosis in Spore Formation: Sexual spores often result from meiosis, ensuring genetic diversity in offspring

Spores, often associated with fungi and plants, are not merely dormant survival structures but also agents of reproduction. Among these, sexual spores stand out due to their origin in meiosis, a process that reshuffles genetic material to create diversity. Unlike asexual spores, which clone the parent organism, sexual spores inherit a unique blend of traits from two parents, enhancing adaptability in changing environments. This genetic recombination is crucial for species survival, particularly in fungi and certain plants, where it drives evolution and resilience.

To understand meiosis in spore formation, consider the life cycle of a fungus like *Aspergillus*. After compatible hyphae (filaments) from two individuals fuse, specialized structures called asci develop. Inside each ascus, diploid cells undergo meiosis, reducing the chromosome number by half and producing haploid spores. These spores, known as ascospores, are then released to germinate and grow into new individuals. This process not only ensures genetic diversity but also allows fungi to colonize new habitats efficiently. For instance, in agricultural settings, understanding this mechanism can help manage fungal pathogens by disrupting their spore production cycles.

The role of meiosis in spore formation extends beyond fungi to plants like ferns and mosses. In ferns, sexual spores (called zoospores in some species) are produced within structures known as sporangia. Meiosis occurs within the sporangium, generating haploid spores that develop into gametophytes—small, heart-shaped structures that produce eggs and sperm. When these gametes unite, a new sporophyte (the familiar fern plant) grows, completing the cycle. This alternation of generations, driven by meiosis, ensures that each generation inherits a unique genetic makeup, fostering adaptability in diverse ecosystems.

Practical applications of this knowledge abound. For gardeners, recognizing the sexual reproduction of fern spores can inform propagation techniques. By collecting spores from mature plants and providing a moist, shaded environment, one can cultivate new ferns with varied traits. Similarly, in biotechnology, manipulating meiosis in spore-forming organisms could lead to improved crop resilience or novel fungal strains for industrial use. However, caution is necessary; disrupting natural meiosis processes can have unintended consequences, such as reduced fitness in offspring.

In conclusion, meiosis in spore formation is a cornerstone of sexual reproduction in many organisms, ensuring genetic diversity through recombination. From fungi to ferns, this process underpins evolutionary success and ecological adaptability. By studying and applying this knowledge, we can harness its benefits while mitigating risks, whether in agriculture, conservation, or biotechnology. Understanding meiosis in spores is not just an academic exercise—it’s a key to unlocking nature’s potential.

Do Mold Spores Die When They Dry Out? The Truth Revealed

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Zygospores in Fungi: Formed by fusion of gametes, zygospores are a sexual spore type in fungi

Zygospores are a testament to the intricate sexual reproduction mechanisms in fungi, formed through the fusion of gametes from compatible individuals. This process, known as karyogamy, results in a thick-walled, highly resilient spore capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. Unlike asexual spores, zygospores are not produced through simple cell division but are the product of a complex genetic exchange, ensuring genetic diversity within fungal populations. This sexual spore type is particularly prominent in certain groups of fungi, such as Zygomycota, where it serves as a critical survival strategy.

To understand the formation of zygospores, consider the steps involved in their development. First, compatible hyphae (filamentous structures of fungi) from two individuals grow toward each other, guided by chemical signals. Once in close proximity, specialized structures called gametangia form at the tips of these hyphae. The gametangia then fuse, allowing the nuclei from each parent to migrate and unite, forming a diploid zygote. This zygote matures into a zygospore, encased in a protective wall that can remain dormant for extended periods. This process highlights the precision and coordination required for sexual reproduction in fungi.

From a practical standpoint, zygospores are of significant interest in agriculture and biotechnology. Their ability to endure extreme conditions, such as desiccation and temperature fluctuations, makes them valuable for preserving fungal genetic material. For example, in crop protection, zygospores of beneficial fungi can be stored and later reintroduced to soil to combat pathogens. Additionally, understanding zygospore formation aids in controlling harmful fungi, as disrupting their sexual reproduction cycle can limit their spread. Researchers often study zygospore-forming fungi to develop targeted fungicides or improve soil health.

Comparatively, zygospores differ from other sexual spore types, such as ascospores and basidiospores, in their structure and ecological role. While ascospores and basidiospores are produced in fruiting bodies (ascocarps and basidiocarps, respectively), zygospores are typically solitary and lack such elaborate structures. This simplicity reflects their primary function as survival units rather than dispersal agents. However, like other sexual spores, zygospores contribute to genetic recombination, which is essential for fungal adaptation and evolution. This distinction underscores the diversity of reproductive strategies within the fungal kingdom.

In conclusion, zygospores exemplify the sophistication of sexual reproduction in fungi, combining genetic diversity with environmental resilience. Their formation through gamete fusion and their ability to withstand adversity make them a fascinating subject of study. Whether in scientific research, agriculture, or biotechnology, understanding zygospores offers practical insights into harnessing fungal biology for human benefit. By focusing on this unique spore type, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways fungi ensure their survival and thrive in diverse ecosystems.

Anaerobic Bacteria and Sporulation: Do All Species Form Spores?

You may want to see also

Oospores in Algae: Sexual spores in algae, like oospores, develop from fertilized eggs for reproduction

Spores are often associated with asexual reproduction, but certain algae challenge this notion with their unique sexual spores called oospores. These specialized structures are the product of a fascinating reproductive strategy in the algal world. Unlike typical spores that develop from single cells, oospores arise from the fusion of male and female gametes, a process akin to sexual reproduction in higher organisms. This distinction is crucial, as it highlights the diversity of reproductive methods in the plant kingdom, even at the microscopic level.

The Formation of Oospores:

In the life cycle of algae, particularly in species like *Sargassum* and *Fucus*, sexual reproduction is a key phase. It begins with the release of male gametes, often flagellated and motile, which swim towards the female reproductive organs. Upon reaching the female gametangium, fertilization occurs, resulting in the formation of a diploid zygote. This zygote then undergoes a series of transformations, developing a thick wall and accumulating nutrients, eventually becoming an oospore. The process is a remarkable example of nature's ingenuity, ensuring the survival and dispersal of algal species.

A Comparative Perspective:

Oospores can be likened to the seeds of higher plants, serving as a means of dispersal and a reservoir of genetic material. However, unlike seeds, oospores are often more resilient, capable of withstanding harsh environmental conditions. This adaptability is essential for algae, which inhabit diverse ecosystems, from freshwater ponds to marine environments. For instance, in the genus *Chara*, oospores can remain dormant for extended periods, only germinating when conditions are favorable, thus ensuring the species' longevity.

Practical Implications:

Understanding oospore development has practical applications in aquaculture and algal cultivation. By manipulating environmental conditions, such as nutrient availability and light exposure, researchers can induce sexual reproduction and oospore formation in controlled settings. This technique is valuable for the mass production of algae, which has numerous industrial applications, including biofuel production and wastewater treatment. For instance, in the cultivation of *Chlorella*, a green alga, inducing oospore formation can lead to more robust and genetically diverse populations, enhancing its potential as a biomass source.

A Natural Wonder:

The sexual reproduction of algae through oospores is a testament to the complexity and diversity of life's reproductive strategies. It challenges the simplistic view of spores as solely asexual entities and reveals a sophisticated mechanism for genetic recombination and survival. As we explore the microscopic world, we uncover intricate processes that contribute to the richness of life on Earth, reminding us that even the smallest organisms have evolved remarkable ways to thrive and perpetuate their existence. This knowledge not only advances our scientific understanding but also inspires appreciation for the natural world's ingenuity.

Do Flowers Release Haploid Wind-Blown Spores? Unraveling Plant Reproduction Myths

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Spores themselves do not reproduce sexually; they are the product of sexual or asexual reproduction in certain organisms, such as fungi, plants, and some bacteria.

Yes, in some organisms like fungi, spores can be the result of sexual reproduction (e.g., zygospores) or can fuse to initiate sexual reproduction (e.g., gametangial spores).

No, spores can be produced through both asexual (e.g., conidia in fungi) and sexual (e.g., meiospores in plants) processes, depending on the organism and its life cycle.