Moss, a resilient and ancient plant, reproduces primarily through spores, which are microscopic, single-celled structures dispersed by wind, water, or animals. These spores, produced in the moss's sporophyte stage, germinate under suitable conditions—typically moist, shaded environments—to form protonema, a thread-like structure that eventually develops into new moss plants. This asexual method of reproduction allows moss to thrive in diverse habitats, from forest floors to rocky outcrops, making it a fascinating subject for understanding plant life cycles and adaptation. Thus, the growth of moss from spores is not only a fundamental biological process but also a key to its widespread success in various ecosystems.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Growth Method | Moss grows from spores, which are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units. |

| Spores Production | Produced in capsules on the moss plant (sporophyte generation) after fertilization. |

| Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals to new locations. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under suitable conditions (moisture, light, substrate) to form protonema, a thread-like structure. |

| Protonema Development | Protonema develops into gametophores (the leafy, recognizable moss plant) through cell division and differentiation. |

| Life Cycle | Moss has an alternation of generations (sporophyte and gametophyte phases), with the gametophyte being the dominant phase. |

| Environmental Requirements | Requires moisture, shade, and acidic to neutral pH soil for optimal growth. |

| Growth Rate | Slow-growing, with spores taking weeks to months to develop into mature moss plants. |

| Reproduction | Can also reproduce vegetatively through fragmentation, but spores are the primary method for new colonies. |

| Ecological Role | Spores allow moss to colonize new habitats and contribute to ecosystem stability in moist environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Moss Life Cycle Basics: Spores germinate into protonema, developing into gametophytes, the visible moss plant

- Spore Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals spread spores to new environments for moss colonization

- Germination Conditions: Spores require moisture, light, and suitable substrate to successfully sprout and grow

- Role of Protonema: Early stage after spore germination, crucial for anchoring and nutrient absorption

- Environmental Factors: Temperature, humidity, and pH levels influence spore viability and moss growth success

Moss Life Cycle Basics: Spores germinate into protonema, developing into gametophytes, the visible moss plant

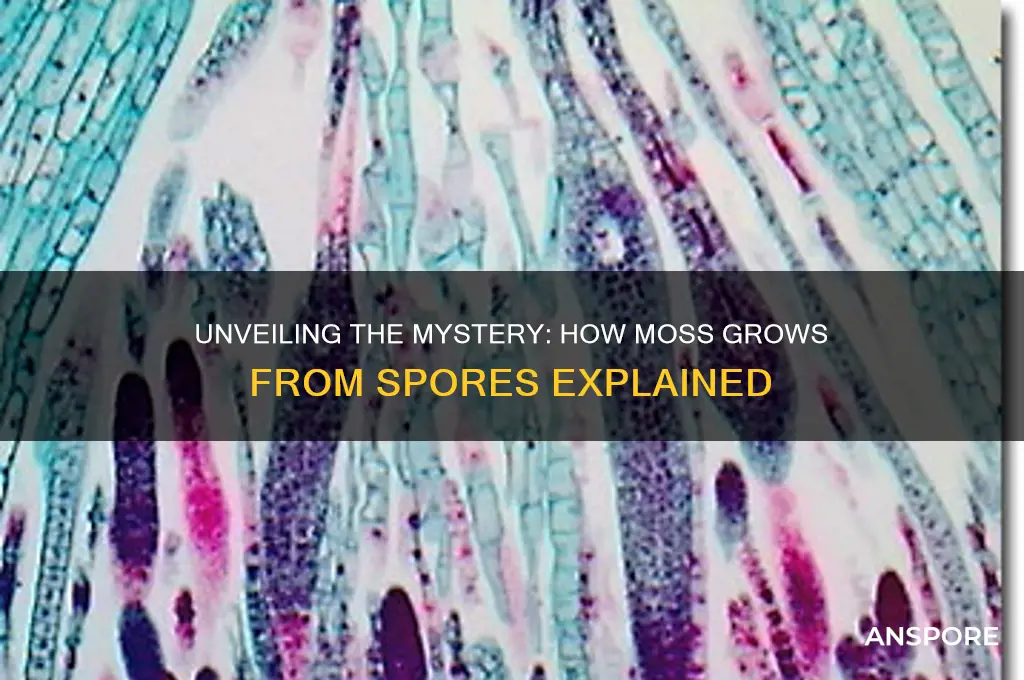

Mosses, unlike most plants, begin their life cycle with a single-celled spore, a lightweight, resilient structure perfectly adapted for wind dispersal. These spores are the starting point of a fascinating journey, germinating under the right conditions of moisture and light. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment, it absorbs water and begins to divide, forming a thread-like structure called the protonema. This stage is crucial, as it anchors the moss to its substrate and sets the foundation for the next phase of growth.

The protonema is not the moss you typically see carpeting forest floors or clinging to rocks. Instead, it’s a delicate, green filament that spreads across surfaces, often resembling a thin, greenish film. From this protonema, buds develop, giving rise to the gametophytes—the visible, leafy moss plants. These gametophytes are the dominant stage of the moss life cycle, producing sex organs (antheridia and archegonia) that allow for reproduction. Understanding this transition from spore to protonema to gametophyte is key to appreciating how mosses thrive in diverse environments, from damp woodlands to arid deserts.

To observe this process firsthand, collect moss spores by gently shaking mature plants over a piece of paper. Sow these spores on a sterile, moist substrate like peat or soil in a clear container to maintain humidity. Keep the container in indirect light and mist regularly to ensure the substrate remains damp. Within a few weeks, you’ll notice the protonema forming, followed by the emergence of tiny gametophytes. This simple experiment not only illustrates the moss life cycle but also highlights the adaptability of these plants to microhabitats.

While the spore-to-protonema-to-gametophyte progression is straightforward, it’s important to note that mosses face challenges in urban or polluted environments. Spores require clean, undisturbed surfaces to germinate, and protonema are sensitive to desiccation. For gardeners or enthusiasts looking to cultivate moss, creating a stable, shaded, and consistently moist environment is essential. Additionally, avoid using fertilizers or pesticides, as mosses absorb nutrients directly through their leaves and are highly susceptible to chemicals.

In comparison to vascular plants, mosses lack true roots, stems, and leaves, yet their life cycle is remarkably efficient. The protonema stage acts as both anchor and nutrient absorber, while the gametophytes focus on photosynthesis and reproduction. This division of labor allows mosses to colonize niches where other plants cannot survive. By studying this life cycle, we gain insights into the resilience of bryophytes and their role in ecosystems as pioneers of barren landscapes and indicators of environmental health.

Are Spores Alive? Exploring the Life Status of Dormant Spores

You may want to see also

Spore Dispersal Methods: Wind, water, and animals spread spores to new environments for moss colonization

Mosses, unlike plants with seeds, rely on spores for reproduction, a process that hinges on efficient dispersal to ensure colonization of new habitats. Wind is perhaps the most ubiquitous method, acting as an invisible courier that carries lightweight spores over vast distances. These spores, often produced in capsules called sporangia, are released into the air in staggering quantities—a single moss plant can disperse thousands of spores in a single release. This strategy maximizes the chances of spores landing in environments conducive to growth, such as damp, shaded areas where moss thrives. However, wind dispersal is unpredictable, and many spores may end up in unsuitable locations, underscoring the importance of sheer volume in this reproductive gamble.

Water, too, plays a critical role in spore dispersal, particularly for moss species inhabiting moist environments. Spores can be carried by raindrop splashes, streams, or even ocean currents, allowing them to travel from one waterlogged substrate to another. This method is especially effective in dense forests or wetlands, where water flow is consistent. For instance, spores from aquatic mosses may hitch a ride on the surface tension of water droplets, eventually settling in crevices or on submerged rocks. While water dispersal is more localized compared to wind, it ensures that spores reach environments with the moisture levels necessary for germination, increasing the likelihood of successful colonization.

Animals, often unwitting participants, contribute to spore dispersal through a process known as zoochory. Small creatures like insects, snails, and even birds can carry spores on their bodies as they move through moss-covered areas. For example, a beetle crawling through a moss patch may pick up spores on its exoskeleton and deposit them elsewhere as it forages. Similarly, birds nesting in mossy habitats can inadvertently transport spores to new locations on their feathers or feet. This method, though less widespread than wind or water, adds a layer of unpredictability and potential for long-distance dispersal, particularly when animals migrate or traverse diverse ecosystems.

Understanding these dispersal methods is not just an academic exercise—it has practical implications for conservation and horticulture. For instance, gardeners cultivating moss for aesthetic purposes can mimic natural dispersal by gently misting spore-laden water onto desired areas or introducing small animals like snails to aid in distribution. Similarly, conservationists restoring moss-dominated ecosystems can strategically place spore sources near water bodies or in windy corridors to enhance natural dispersal. By leveraging these mechanisms, humans can facilitate moss colonization in degraded habitats, preserving biodiversity and the ecological functions mosses provide, such as soil stabilization and moisture retention.

In conclusion, the dispersal of moss spores through wind, water, and animals is a multifaceted process that ensures the survival and spread of these resilient plants. Each method has its strengths and limitations, but together they form a robust system that has allowed mosses to thrive in diverse environments for millions of years. Whether through the whims of the wind, the flow of water, or the movements of animals, spores find their way to new habitats, ready to germinate and continue the cycle of life. This intricate dance of dispersal highlights the adaptability and ecological significance of mosses, making them a fascinating subject for both scientific study and practical application.

Can Carbon Filters Effectively Remove Mold Spores from Indoor Air?

You may want to see also

Germination Conditions: Spores require moisture, light, and suitable substrate to successfully sprout and grow

Mosses, unlike seeds, rely on spores for reproduction, and these microscopic units are the starting point of their life cycle. For successful germination, spores demand specific environmental cues, primarily moisture, light, and a suitable substrate. This trio of conditions is non-negotiable, as each plays a distinct role in triggering and sustaining the growth process. Moisture, for instance, is essential to activate the dormant spore, initiating metabolic processes that lead to sprouting. Without adequate water, spores remain inert, unable to progress to the next stage of development.

Light, though often overlooked, is another critical factor. While mosses can tolerate low-light conditions, spores require a certain threshold of light exposure to signal the onset of germination. This light sensitivity is species-specific, with some mosses thriving in shaded environments and others needing partial sunlight. For example, *Sphagnum* moss spores often germinate in dimly lit peatlands, whereas *Bryum* species prefer brighter, open habitats. Understanding these light requirements is key to cultivating moss successfully, whether in a garden or laboratory setting.

The substrate, or the surface on which spores land, must be conducive to growth. Moss spores are highly selective, favoring materials that retain moisture while providing stability. Common substrates include soil, rock, bark, and even concrete, provided they are free from competing vegetation and excessive nutrients. Interestingly, some mosses, like *Ceratodon purpureus*, are pioneers, colonizing bare, nutrient-poor surfaces where other plants cannot survive. This adaptability highlights the importance of matching the substrate to the moss species for optimal germination.

Practical application of these conditions requires careful consideration. For hobbyists or researchers, creating a controlled environment is essential. A simple setup involves misting spores onto a damp, shaded surface, ensuring consistent moisture without waterlogging. Light exposure can be managed using grow lights or natural sunlight filtered through sheer fabric. Monitoring these factors over time allows for adjustments, increasing the likelihood of successful germination. Patience is paramount, as moss growth is slow, with visible colonies often taking weeks to months to establish.

In summary, the germination of moss spores is a delicate interplay of moisture, light, and substrate. Each condition must be precisely managed to mimic the moss’s natural habitat. By understanding and replicating these requirements, enthusiasts and scientists alike can unlock the potential of these resilient plants, fostering their growth in diverse settings. Whether for ecological restoration, decorative purposes, or scientific study, mastering these germination conditions is the first step in cultivating moss from its earliest form.

Mold Spores and Sore Throats: Uncovering the Hidden Connection

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of Protonema: Early stage after spore germination, crucial for anchoring and nutrient absorption

Mosses, unlike vascular plants, begin their life cycle with a delicate yet vital structure known as the protonema. This thread-like or sheet-like growth emerges immediately after spore germination, serving as the foundation for the moss’s future development. Think of it as the moss’s embryonic stage, a transient but indispensable phase that bridges the gap between spore and mature plant. Without the protonema, mosses would lack the means to establish themselves in their environment, making it a cornerstone of their survival strategy.

The protonema’s primary role is twofold: anchoring the moss to its substrate and absorbing essential nutrients from the surroundings. For instance, in humid environments like forests or wetlands, the protonema secretes a sticky substance that adheres to rocks, soil, or bark, ensuring the moss remains firmly attached. This anchoring mechanism is critical, as mosses lack true roots and rely on this initial foothold to withstand environmental stresses such as wind or water flow. Simultaneously, the protonema acts as a nutrient scavenger, absorbing water and minerals directly from its environment through its thin, permeable cell walls. This dual functionality highlights the protonema’s efficiency as a survival tool in nutrient-poor habitats.

To visualize its importance, consider a moss spore landing on a damp rock. Within days, the protonema begins to grow, spreading across the surface like a green web. This growth is not random; it’s a strategic expansion aimed at maximizing surface contact for both stability and nutrient uptake. Practical observations show that protonema can grow up to 1 cm in length under optimal conditions, though its size varies depending on species and environmental factors. For gardeners or enthusiasts cultivating moss, maintaining a moist substrate during this stage is crucial, as dehydration can halt protonema development and doom the moss’s chances of survival.

Comparatively, the protonema’s role is akin to the radicle in seed-bearing plants, though it serves a broader function. While the radicle primarily anchors the seedling and initiates root growth, the protonema is both anchor and nutrient absorber, laying the groundwork for the moss’s gametophyte stage. This distinction underscores the unique adaptations of mosses to their environments, where resources are often scarce and competition is fierce. By mastering this early stage, mosses ensure their longevity in ecosystems where other plants might struggle.

In conclusion, the protonema is not merely a fleeting stage in the moss life cycle but a critical determinant of its success. Its ability to anchor and absorb nutrients sets the stage for the moss’s entire lifecycle, making it a fascinating subject for both scientific study and practical application. Whether you’re a botanist, a gardener, or simply a nature enthusiast, understanding the protonema’s role offers valuable insights into the resilience and ingenuity of these ancient plants.

Understanding Fungal Allergies: Can You React to Fungal Spores?

You may want to see also

Environmental Factors: Temperature, humidity, and pH levels influence spore viability and moss growth success

Mosses, unlike many plants, do not rely on seeds for reproduction but instead disperse through spores, microscopic units of life that can travel vast distances on air currents. However, the journey from spore to thriving moss colony is fraught with environmental challenges. Temperature, humidity, and pH levels act as gatekeepers, determining whether spores germinate and develop into healthy moss plants.

Understanding these factors is crucial for anyone seeking to cultivate moss, whether for aesthetic purposes, ecological restoration, or scientific study.

Temperature: Moss spores, like all living organisms, have optimal temperature ranges for growth. Most moss species thrive in cool, moist environments, with ideal temperatures ranging between 50°F and 70°F (10°C and 21°C). Extreme heat can desiccate spores, rendering them inviable, while freezing temperatures can damage their delicate cellular structures. For successful moss cultivation, maintain a consistent temperature within this range, avoiding sudden fluctuations.

Consider using a greenhouse or terrarium to provide controlled conditions, especially in regions with extreme climates.

Humidity: Water is essential for spore germination and moss growth. High humidity levels, ideally above 70%, are crucial for keeping spores hydrated and facilitating the development of protonema, the initial filamentous stage of moss growth. Misting the substrate regularly or using a humidifier can help maintain optimal moisture levels. However, excessive moisture can lead to fungal growth, so ensure proper ventilation to prevent waterlogging.

For outdoor moss gardens, choose shaded areas with naturally higher humidity levels, such as near water features or in woodland settings.

PH Levels: The acidity or alkalinity of the substrate, measured by pH, significantly impacts moss growth. Most moss species prefer acidic to neutral conditions, with optimal pH ranges between 5.0 and 7.0. Alkaline soils can hinder nutrient uptake and stunt growth. Test the pH of your substrate using a simple testing kit and adjust it if necessary using sulfur or lime amendments. Remember, drastic pH changes can be harmful, so make gradual adjustments and monitor the moss's response.

By carefully controlling temperature, humidity, and pH levels, you can create an environment conducive to moss spore germination and growth. This knowledge empowers you to cultivate these fascinating plants, contributing to the beauty and biodiversity of your surroundings. Remember, patience and observation are key, as mosses grow slowly and respond subtly to environmental changes. With dedication and an understanding of these environmental factors, you can unlock the secrets of moss cultivation and witness the magic of spores transforming into lush, verdant carpets.

Do All Viruses Have Spores? Unraveling the Myth and Facts

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, moss grows from spores, which are tiny, single-celled reproductive units produced by mature moss plants.

Moss spores are lightweight and can be dispersed by wind, water, animals, or even human activity to colonize new areas.

No, moss spores require specific conditions like moisture, shade, and a suitable substrate to germinate and grow into new plants.

The time for moss to grow from spores varies, but it typically takes several weeks to months, depending on environmental conditions.

While all mosses reproduce via spores, the specific growth requirements and timelines can differ slightly between species.