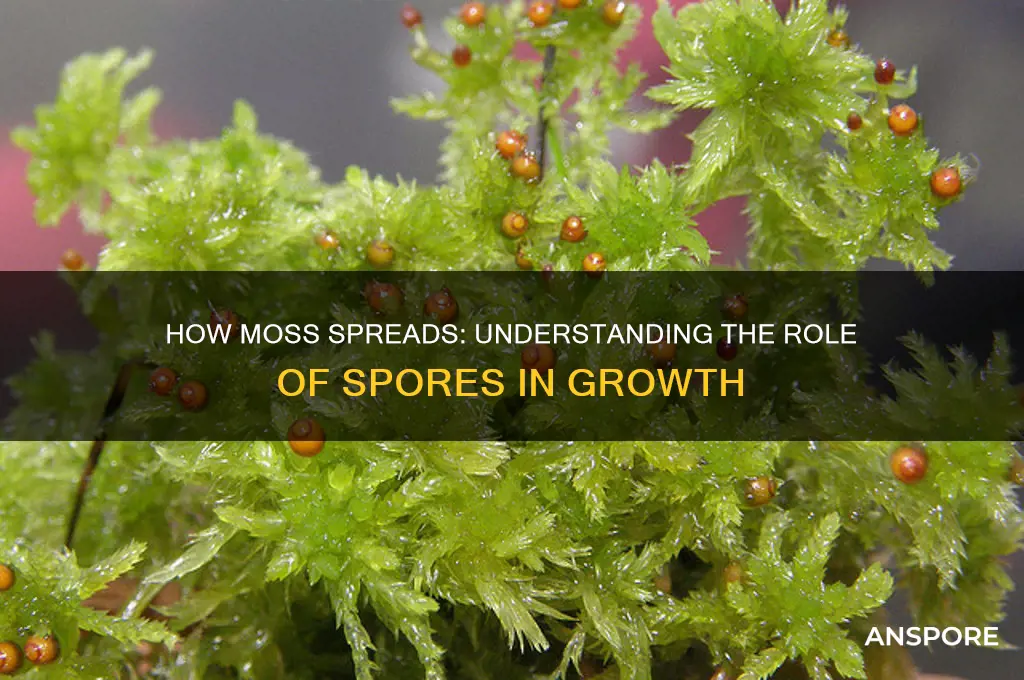

Mosses are a diverse group of non-vascular plants that reproduce primarily through the dispersal of spores, a process known as sporulation. Unlike flowering plants that rely on seeds, mosses produce tiny, lightweight spores within specialized structures called sporangia, typically located on the tips of stalks called setae. These spores are released into the air and can travel significant distances, allowing mosses to colonize new habitats. Once a spore lands in a suitable environment with adequate moisture and light, it germinates into a protonema, a thread-like structure that eventually develops into a mature moss plant. This method of reproduction ensures the widespread distribution of mosses across various ecosystems, from forests and wetlands to rocky outcrops and urban environments. Understanding how mosses spread by spores provides insight into their resilience and adaptability in diverse ecological niches.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Method of Spread | Moss primarily spreads through spores, which are microscopic, single-celled reproductive units. |

| Sporophyte Structure | Moss produces spores in a capsule on a stalk called the sporophyte, which grows from the gametophyte (the green, leafy part of the moss). |

| Spore Dispersal | Spores are dispersed by wind, water, or animals, allowing moss to colonize new areas. |

| Germination | Spores germinate under suitable conditions (moisture, shade, and appropriate substrate) to form protonema, which develops into new gametophytes. |

| Asexual Reproduction | Moss can also spread asexually through fragmentation of the gametophyte, but spore dispersal is the primary method. |

| Habitat Adaptation | Spores enable moss to survive harsh conditions and colonize diverse habitats, including rocks, soil, and tree bark. |

| Life Cycle | Moss has an alternation of generations life cycle, with both sporophyte (spore-producing) and gametophyte (gamete-producing) stages. |

| Spore Production | A single moss plant can produce thousands to millions of spores, ensuring widespread dispersal. |

| Environmental Requirements | Spores require specific environmental conditions (e.g., moisture, temperature) to germinate successfully. |

| Ecological Role | Moss spores contribute to ecosystem processes, such as soil formation and moisture retention, in various environments. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Moss Spores: How They Form

Mosses, unlike flowering plants, do not produce seeds; instead, they rely on spores for reproduction. These spores are microscopic, single-celled structures that develop within specialized organs called sporangia, typically located on the moss plant’s sporophyte generation. The formation of moss spores is a fascinating process that begins with the fusion of gametes—male sperm and female egg cells—during fertilization. This union results in the growth of a sporophyte, which emerges from the gametophyte (the leafy, green part of the moss). The sporophyte consists of a stalk (seta) and a capsule (sporangium) where spore production occurs.

The lifecycle of mosses is alternation of generations, meaning it alternates between a gametophyte phase (haploid) and a sporophyte phase (diploid). Spores are produced via meiosis within the sporangium, ensuring genetic diversity. As the sporangium matures, it dries out, and the spores are released through a small opening called the peristome. This mechanism is often triggered by environmental factors such as wind or changes in humidity. Once released, spores are dispersed, and under favorable conditions, they germinate into protonema, a thread-like structure that eventually develops into new gametophytes.

To observe moss spore formation, one can collect mature moss specimens with visible sporophytes. Place the moss in a humid environment, such as a sealed container with moist paper towels, to encourage spore release. Over time, the sporangium will dry and split open, releasing a cloud of spores. For educational purposes, a magnifying glass or microscope can be used to examine the spores, which are typically 8–50 micrometers in diameter. This hands-on approach provides a tangible understanding of the spore formation process.

While moss spores are resilient and can survive harsh conditions, their successful germination depends on specific environmental factors. Spores require moisture, shade, and a suitable substrate like soil or rock to develop into protonema. For gardeners or enthusiasts looking to cultivate moss, creating a damp, shaded area and sprinkling collected spores can initiate growth. Patience is key, as mosses grow slowly, but the process of nurturing them from spore to mature plant is deeply rewarding. Understanding spore formation not only highlights the unique biology of mosses but also empowers individuals to propagate these ancient plants effectively.

Ostrich Ferns and Their Spore-Bearing Secrets: Unveiling Nature's Mystery

You may want to see also

Spores vs. Fragments: Spread Methods

Mosses, ancient and resilient, employ two primary strategies to colonize new territories: spores and fragments. Spores, microscopic and lightweight, are the moss’s answer to seeds. Produced in capsules atop mature plants, they disperse via wind, water, or animals, traveling vast distances to settle in suitable habitats. This method ensures genetic diversity and allows mosses to reach remote or inaccessible areas. However, spore germination is unpredictable, requiring specific moisture and light conditions to succeed. In contrast, fragmentation relies on the moss’s modular structure. When pieces break off—whether by foot traffic, weather, or wildlife—they can regenerate into new plants if conditions are favorable. This method is localized but highly efficient, as fragments already possess the necessary structures to grow. While spores prioritize exploration, fragments excel in exploitation, rapidly expanding established colonies.

Consider a forest floor where moss thrives. Spores from a single plant might land meters away, but only a fraction will germinate due to competition and environmental constraints. Meanwhile, a fragment dislodged by a passing deer could root within centimeters, doubling the moss’s coverage in weeks. This duality highlights the moss’s adaptive brilliance: spores hedge bets on distant opportunities, while fragments capitalize on proven terrain. For gardeners or conservationists, understanding this balance is key. Encouraging spore dispersal might require open spaces and air movement, whereas fragment-based growth benefits from undisturbed, moist environments.

From a practical standpoint, propagating moss intentionally leverages both methods. To use spores, collect capsules from mature plants in late summer, dry them indoors to release spores, and sprinkle these onto a damp, shaded substrate. Keep the area consistently moist, and within weeks, protonema (the initial growth stage) will appear. For fragmentation, simply tear small pieces from an existing moss patch and press them into soil or stone crevices. Mist regularly to prevent drying, and the fragments will anchor and spread. This hands-on approach mimics natural processes, offering control over where and how moss colonizes.

The choice between spores and fragments depends on the goal. Spores are ideal for introducing moss to new areas or restoring degraded habitats, though patience is required. Fragments are better for quick, targeted expansion within a confined space, such as a garden path or green roof. Combining both methods can maximize success, especially in diverse landscapes. For instance, sow spores in open, sunny spots while planting fragments in shaded, sheltered areas. Monitoring moisture levels is critical for both—mosses thrive in humidity but drown in waterlogging.

Ultimately, the spore-fragment dichotomy reflects the moss’s evolutionary ingenuity. By deploying two distinct strategies, mosses ensure survival across varying conditions, from windswept cliffs to dense forests. For enthusiasts, this knowledge transforms moss cultivation from guesswork into a strategic art. Whether you’re a gardener, ecologist, or hobbyist, tailoring your approach to these methods unlocks the full potential of these remarkable plants. Observe, experiment, and let the mosses teach you their secrets.

Can Mold Spores Spread Through Vents? Understanding Air Duct Contamination

You may want to see also

Wind Dispersal of Moss Spores

Mosses, unlike their vascular plant cousins, lack true roots, stems, and seeds, relying instead on spores for reproduction. These microscopic, single-celled units are produced in vast quantities within the capsule of the moss plant. When mature, the capsule dries and splits open, releasing the spores into the surrounding environment. This is where wind steps in as a crucial agent of dispersal.

Wind dispersal is a passive yet highly effective strategy for mosses. Due to their minuscule size and lightweight nature, spores can be easily carried by even the gentlest breeze. This allows them to travel considerable distances, potentially reaching new habitats far from the parent plant. Imagine a single moss capsule releasing thousands of spores, each a tiny vessel of genetic potential, riding the wind currents like microscopic explorers.

The success of wind dispersal for mosses lies in its unpredictability. While some spores may land in unsuitable environments, others will find themselves in moist, shaded areas conducive to germination. This scattergun approach ensures that at least a portion of the spores will find favorable conditions, increasing the species' chances of survival and colonization.

It's important to note that wind dispersal is not the only method employed by mosses. Water can also play a role, especially in aquatic or damp environments. However, wind's reach and omnipresence make it a dominant force in moss spore dispersal, contributing significantly to the widespread distribution of these ancient plants. Understanding this process not only sheds light on the fascinating reproductive strategies of mosses but also highlights the intricate interplay between organisms and their environment.

Eukaryotic Organisms and Spore Reproduction: Exploring Asexual Strategies in Nature

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Water Role in Spore Spread

Mosses, unlike vascular plants, lack true roots, stems, and leaves, relying instead on spores for reproduction. These microscopic spores are lightweight and easily dispersed, but their journey to new habitats is often facilitated by water. Raindrops, splashing onto moss-covered surfaces, act as tiny catapults, launching spores into the air. This mechanism, known as splash dispersal, is a primary method for mosses to colonize new areas. The effectiveness of this process depends on the moisture content of the environment; in humid conditions, spores remain viable longer, increasing the likelihood of successful dispersal.

Consider the role of water bodies in spore spread. Streams, rivers, and even puddles can transport moss spores over considerable distances. Spores that land on water surfaces may adhere to debris or form part of the biofilm, traveling downstream until they reach a suitable substrate. This aquatic pathway is particularly significant in forested areas where water flow is consistent. For instance, in temperate rainforests, moss spores can travel miles along waterways, contributing to the dense moss carpets often observed in these ecosystems.

To maximize the role of water in spore spread, gardeners and landscapers can employ specific techniques. Creating small water features, such as shallow ponds or trickling streams, near moss-covered areas can enhance spore dispersal. Additionally, misting mosses regularly with water not only keeps them hydrated but also simulates rain, encouraging spore release. For optimal results, use a fine mist setting and apply water in the early morning or late afternoon to mimic natural conditions.

A comparative analysis reveals that while wind is often considered the primary agent for spore dispersal, water plays a more targeted and efficient role in moss propagation. Wind dispersal is indiscriminate, scattering spores widely but with lower precision. Water, on the other hand, often delivers spores directly to moist, shaded areas—ideal conditions for moss growth. This specificity makes water a more reliable medium for establishing new moss colonies, particularly in controlled environments like gardens or green roofs.

Finally, understanding the interplay between water and moss spore spread has practical implications for conservation and restoration efforts. In degraded habitats, reintroducing mosses can stabilize soil and improve biodiversity. By strategically placing water sources or directing water flow, conservationists can enhance spore dispersal to targeted areas. For example, in post-fire landscapes, installing temporary irrigation systems can facilitate moss colonization, aiding in ecosystem recovery. This approach underscores the importance of water not just as a life-sustaining element but as a tool for ecological restoration.

Clostridia's Survival Strategy: Understanding Spore-Based Reproduction Mechanisms

You may want to see also

Germination: Spores to Moss Growth

Mosses, ancient and resilient, reproduce primarily through spores, a process that begins with germination—a delicate yet robust mechanism that transforms microscopic spores into thriving moss colonies. Unlike seeds, spores are unicellular and lack stored nutrients, relying instead on environmental cues to initiate growth. When a spore lands in a suitable habitat—moist, shaded, and rich in organic matter—it absorbs water, swelling and rupturing its protective wall. This triggers the development of a protonema, a thread-like structure that serves as the foundation for future moss growth. Understanding this initial stage is crucial for anyone cultivating moss or studying its ecology, as it highlights the plant’s dependence on specific conditions to thrive.

The germination process is highly sensitive to environmental factors, particularly moisture and light. Spores require a consistently damp surface to activate, as water is essential for cellular expansion and metabolic processes. In nature, this often occurs in microhabitats like crevices, tree bark, or soil surfaces where moisture lingers. Light, though not always necessary, can influence the direction and rate of protonema growth, with some species showing phototropic responses. For enthusiasts attempting to grow moss, maintaining a humidity level above 80% and providing diffused light can significantly enhance germination success. Patience is key, as this stage can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks, depending on species and conditions.

Once the protonema establishes itself, it undergoes a series of transformations that mark the transition from spore to mature moss. The protonema develops buds, which grow into leafy gametophytes—the recognizable, carpet-like structures associated with moss. This phase is critical for colonization, as the gametophytes produce rhizoids that anchor the moss and absorb water and nutrients. Interestingly, some moss species can also reproduce asexually during this stage, forming gemmae—small, disc-like structures that disperse and grow into new plants. This dual reproductive strategy underscores moss’s adaptability and explains its ability to spread rapidly in favorable environments.

Practical applications of this knowledge are vast, from landscaping to ecological restoration. For instance, gardeners can accelerate moss growth by scattering spores on prepared substrates, such as a mix of soil and sand, kept consistently moist. In conservation efforts, understanding germination allows for targeted reintroduction of moss species in degraded habitats, aiding biodiversity recovery. However, caution is advised when collecting spores, as over-harvesting can deplete natural populations. Instead, sourcing spores from cultivated moss or specialized suppliers ensures sustainability. By mastering the germination process, individuals can harness moss’s unique biology to create lush, green spaces or contribute to environmental restoration projects.

Do Seed Plants Disperse Spores? Unraveling Plant Reproduction Mysteries

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, moss primarily spreads by releasing spores, which are microscopic reproductive units that disperse through wind, water, or animals.

Moss spores travel through natural means like wind, water splashes, or by attaching to animals or clothing, allowing them to reach new environments.

While spores are the main method, moss can also spread through fragmentation, where small pieces of the plant break off and grow into new moss in suitable conditions.

It can take several weeks to months for moss spores to germinate and grow into visible moss, depending on environmental conditions like moisture, light, and temperature.