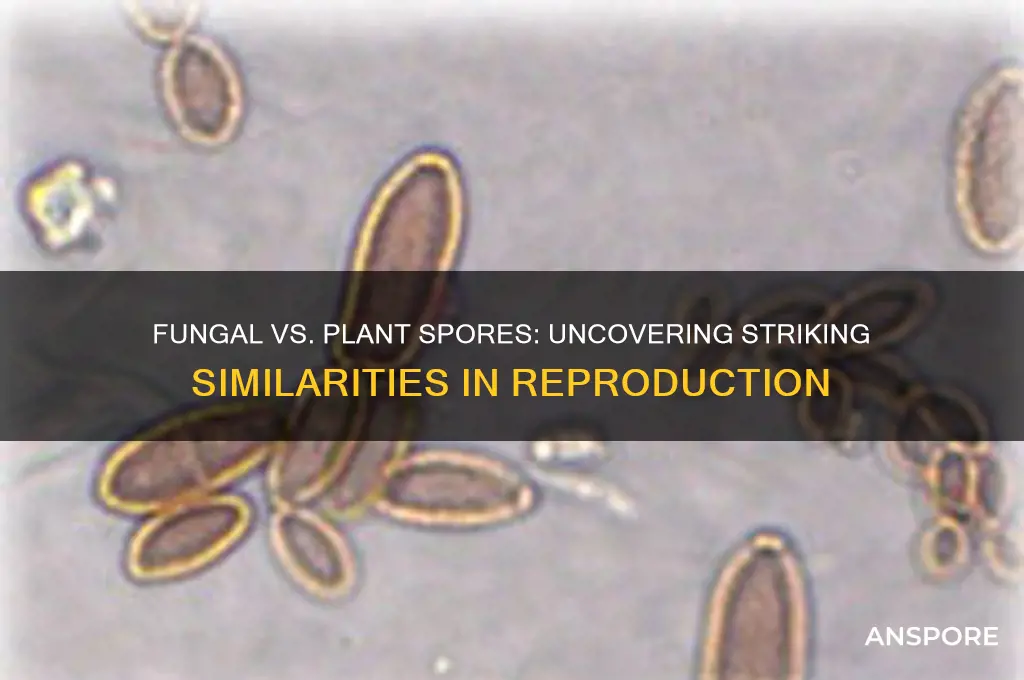

Fungal spores and plant spores share several similarities in their structure, function, and ecological roles. Both are reproductive units designed for dispersal and survival in diverse environments, often lightweight and equipped with adaptations to withstand harsh conditions such as drought or extreme temperatures. Structurally, they are typically unicellular and may possess protective outer layers, such as a cell wall, to ensure durability during dispersal. Functionally, both types of spores serve as a means of asexual or sexual reproduction, allowing organisms to colonize new habitats efficiently. Additionally, they rely on wind, water, or animals for dispersal, highlighting their convergent evolutionary strategies to propagate and thrive in various ecosystems. These parallels underscore the shared challenges faced by fungi and plants in their reproductive cycles.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Reproduction | Both fungal and plant spores are reproductive structures used for propagation and survival. |

| Dispersal | Spores of both fungi and plants are lightweight and easily dispersed by wind, water, or animals to colonize new habitats. |

| Dormancy | They can remain dormant for extended periods, surviving harsh environmental conditions until favorable conditions return. |

| Genetic Material | Both types of spores carry genetic material necessary for the development of a new organism. |

| Asexual Reproduction | Many fungal and plant spores are produced asexually through processes like sporulation or fragmentation. |

| Environmental Resistance | Spores of both fungi and plants have protective outer layers (e.g., cell walls) that provide resistance to environmental stressors like desiccation and UV radiation. |

| Size | They are typically microscopic, allowing for efficient dispersal and colonization. |

| Diversity | Both fungi and plants produce a wide variety of spore types adapted to different environments and dispersal mechanisms. |

| Ecological Role | Spores play a crucial role in ecosystem dynamics, contributing to nutrient cycling, decomposition, and plant reproduction. |

| Germination | Under suitable conditions, both fungal and plant spores can germinate and develop into new individuals. |

Explore related products

$13.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

- Dispersal Mechanisms: Both use wind, water, animals for wide dispersal to reach new habitats

- Survival Structures: Spores are durable, resistant to harsh conditions, ensuring long-term survival

- Reproduction Role: Both serve as primary reproductive units for fungi and plants

- Light Sensitivity: Spores often germinate in response to light cues for optimal growth

- Size and Shape: Tiny, lightweight structures designed for efficient dispersal and colonization

Dispersal Mechanisms: Both use wind, water, animals for wide dispersal to reach new habitats

Fungal and plant spores share a critical survival strategy: leveraging external forces for dispersal. Wind, water, and animals act as their primary vehicles, ensuring spores travel far beyond their origin to colonize new habitats. This mechanism is essential for both fungi and plants to thrive in diverse environments, from dense forests to arid deserts. Without such dispersal, their growth would be confined, limiting genetic diversity and ecological impact.

Consider the role of wind, the most common dispersal agent. Fungal spores, like those of the common mold *Aspergillus*, are lightweight and easily carried by air currents. Similarly, plant spores, such as those from ferns, are designed for aerodynamic efficiency. Both types of spores can travel miles, sometimes even crossing continents, thanks to wind patterns. For instance, a single fungal spore released in a forest can land on a rooftop in a nearby city, while fern spores dispersed in a meadow might find their way to a mountain slope. To maximize wind dispersal, both fungi and plants often release spores in large quantities, increasing the odds of successful colonization.

Water serves as another vital dispersal medium, particularly for species near rivers, lakes, or oceans. Fungal spores, like those of aquatic fungi, can float on water surfaces, drifting to new locations. Plant spores, such as those from water ferns or mosses, exhibit similar behavior. This method is especially effective in humid or aquatic ecosystems, where water flow is consistent. For gardeners or ecologists, understanding this mechanism can inform strategies for controlling or encouraging the spread of specific species. For example, planting water-dispersed plants upstream can help establish vegetation in eroded riverbanks.

Animals, both large and small, play a unique role in spore dispersal. Fungal spores often attach to the fur or feathers of animals, hitching a ride to new areas. Similarly, plant spores, like those of burr-producing plants, cling to animal coats. Even insects, such as bees and ants, inadvertently carry spores while foraging. This symbiotic relationship benefits both the spores and the animals, as the latter often gain access to food sources in newly colonized areas. For instance, mycorrhizal fungi dispersed by animals can enhance soil health, benefiting plant growth in turn.

In practical terms, recognizing these dispersal mechanisms can guide conservation efforts and agricultural practices. For example, preserving wind corridors in urban areas can aid the natural spread of beneficial fungi and plants. Similarly, protecting waterways ensures the continued dispersal of aquatic species. By mimicking these natural processes, such as using animal carriers for seed dispersal in reforestation projects, humans can work in harmony with these strategies. Whether in a backyard garden or a large-scale ecosystem restoration, understanding and leveraging these mechanisms can foster biodiversity and resilience.

Does the Sporophyte Produce Spores? Unraveling Plant Life Cycle Secrets

You may want to see also

Survival Structures: Spores are durable, resistant to harsh conditions, ensuring long-term survival

Spores, whether fungal or plant, are nature's ultimate survival capsules, engineered to endure extreme conditions that would destroy most life forms. These microscopic structures are not just reproductive units; they are fortresses designed to withstand desiccation, radiation, and temperature extremes. For instance, fungal spores can remain viable for decades, even centuries, in soil, while plant spores like those of ferns and mosses can survive freezing temperatures and drought. This durability is not a coincidence but a critical adaptation that ensures the long-term survival of the species.

Consider the mechanism behind this resilience. Both fungal and plant spores achieve their hardiness through a combination of structural and biochemical strategies. Their cell walls are often thickened and composed of robust materials like chitin in fungi and sporopollenin in plants, which provide a protective barrier against physical and chemical stressors. Additionally, spores enter a state of metabolic dormancy, reducing their need for water and nutrients while minimizing damage from reactive oxygen species. This dormancy is so profound that spores can revive even after being exposed to the vacuum of space, as demonstrated in experiments with fungal spores aboard the International Space Station.

To harness this survival prowess in practical applications, researchers are exploring spore-inspired technologies. For example, spores' resistance to radiation has led to their use in developing radiation-resistant materials for space exploration. Similarly, their ability to withstand desiccation is being studied to improve the shelf life of vaccines and other biologics, which could revolutionize healthcare in remote or resource-limited areas. By understanding the molecular basis of spore durability, scientists aim to replicate these traits in synthetic systems, offering solutions to challenges in preservation and sustainability.

However, the very traits that make spores resilient also pose challenges. Their ability to persist in the environment can lead to issues like fungal infections in humans or the spread of plant diseases. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores, ubiquitous in indoor environments, can cause severe respiratory conditions in immunocompromised individuals. Similarly, plant spores like those of ragweed contribute to seasonal allergies, affecting millions annually. Managing these risks requires strategies such as air filtration systems and fungicides, highlighting the dual nature of spores as both marvels of survival and potential threats.

In conclusion, the durability of fungal and plant spores is a testament to the ingenuity of evolution, providing a blueprint for survival in the harshest conditions. By studying these structures, we not only gain insights into the natural world but also unlock practical applications that can benefit humanity. Whether in space exploration, medicine, or agriculture, the lessons from spores remind us of the power of adaptation and the importance of resilience in the face of adversity.

Is Spore Still Functional? Troubleshooting Tips for Modern Systems

You may want to see also

Reproduction Role: Both serve as primary reproductive units for fungi and plants

Fungal and plant spores share a fundamental purpose: they are the primary agents of reproduction for their respective organisms. This similarity is not merely coincidental but reflects a convergent evolutionary strategy to ensure survival and dispersal in diverse environments. Both types of spores are lightweight, resilient, and capable of remaining dormant for extended periods, allowing them to withstand harsh conditions until favorable growth opportunities arise. For instance, fungal spores like those of *Aspergillus* and plant spores from ferns or mosses can persist in soil or air for years, waiting for the right combination of moisture, temperature, and nutrients to germinate.

Consider the reproductive efficiency of these spores. A single fungal organism, such as a mushroom, can release millions of spores in a single dispersal event, while a fern can produce thousands of spores on the undersides of its fronds. This high volume ensures that at least some spores will land in suitable environments, increasing the species' chances of propagation. Similarly, both fungal and plant spores are designed for dispersal over long distances—fungal spores via wind or water, and plant spores often aided by wind, animals, or explosive mechanisms like those seen in spore-bearing plants like sphagnum moss.

The structural adaptations of these spores further highlight their reproductive role. Fungal spores, such as those of yeasts or molds, are often encased in protective walls made of chitin, which shields them from desiccation and predators. Plant spores, on the other hand, are typically encased in a tough outer layer called the exine, which provides similar protection. These protective measures ensure that spores can survive the journey from parent organism to new habitat, where they can germinate and establish new individuals.

Practical applications of this knowledge are evident in agriculture and horticulture. For example, understanding spore dispersal helps farmers manage fungal diseases like powdery mildew in crops by implementing timely fungicide applications or adjusting planting schedules. Similarly, gardeners use spore-based propagation techniques for plants like orchids or ferns, where spores are sown on sterile media to grow into new plants. By mimicking natural dispersal mechanisms, such as controlled humidity and airflow, these methods enhance germination rates and ensure healthy plant development.

In conclusion, the reproductive role of fungal and plant spores underscores their significance as evolutionary marvels. Their shared function as primary reproductive units, combined with specialized adaptations for survival and dispersal, highlights the ingenuity of nature in ensuring the continuity of life. Whether in a forest ecosystem or a laboratory setting, understanding these spores' mechanisms provides valuable insights for both scientific research and practical applications, bridging the gap between biology and human innovation.

Does Spor-Klenz Effectively Kill Mold? A Comprehensive Review

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Light Sensitivity: Spores often germinate in response to light cues for optimal growth

Spores, whether fungal or plant, are remarkably attuned to environmental cues, and light sensitivity stands out as a critical factor in their germination. This phenomenon, known as photodormancy or photostimulation, ensures that spores awaken only when conditions are optimal for growth. For instance, fungal spores like those of *Neurospora crassa* require specific wavelengths of light, particularly in the blue spectrum (400–500 nm), to trigger germination. Similarly, plant spores, such as those of ferns and mosses, often rely on red and far-red light (600–700 nm) to signal the presence of suitable habitats. This shared sensitivity to light underscores a convergent evolutionary strategy: both fungal and plant spores use light as a reliable indicator of surface exposure and resource availability.

To harness this light sensitivity in practical applications, consider the following steps. For fungal spores, exposure to blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for 12–24 hours can significantly enhance germination rates, particularly in laboratory settings. For plant spores, a brief pulse of red light followed by far-red light can simulate the transition from shade to sunlight, encouraging germination in shaded environments. However, caution is necessary: overexposure to intense light, especially UV radiation, can damage spore DNA and inhibit growth. Always use light sources with controlled intensity and duration, and shield spores from direct sunlight unless specifically required for the species in question.

The analytical perspective reveals why light sensitivity is so crucial. Light not only signals the presence of a surface but also provides spatial orientation. For example, fungal spores often germinate toward light sources, a behavior known as phototropism, which helps them grow in directions with higher nutrient availability. Plant spores exhibit similar responses, aligning their growth with light to maximize photosynthesis. This shared mechanism highlights the efficiency of light as an environmental cue, allowing both fungal and plant spores to optimize their chances of survival and proliferation in diverse ecosystems.

From a persuasive standpoint, understanding light sensitivity in spores opens doors to innovative agricultural and ecological practices. By manipulating light spectra and timing, farmers and researchers can enhance seedling establishment in crops and restore degraded ecosystems more effectively. For instance, using blue light to stimulate fungal spore germination in mycorrhizal inoculants can improve plant nutrient uptake, while tailored light treatments for plant spores can boost reforestation efforts. This knowledge not only bridges the gap between fungal and plant biology but also empowers us to work in harmony with natural processes for sustainable outcomes.

Finally, a comparative analysis reveals intriguing differences in how fungal and plant spores respond to light. While both rely on photoreceptors like phytochromes and cryptochromes, the specific wavelengths and durations required vary. Fungal spores often prioritize blue light for germination, whereas plant spores may integrate multiple light signals for more complex responses. Despite these differences, the underlying principle remains the same: light acts as a universal cue for optimal growth. By studying these similarities and differences, we gain a deeper appreciation for the elegance of spore biology and its potential applications across disciplines.

Can Your Body Naturally Combat Tetanus Spores? Unveiling the Truth

You may want to see also

Size and Shape: Tiny, lightweight structures designed for efficient dispersal and colonization

Fungal and plant spores share a remarkable design feature: their minuscule size and lightweight structure, optimized for dispersal and colonization. Typically measuring between 1 and 100 micrometers, these spores are invisible to the naked eye, yet their impact on ecosystems is profound. This tiny scale reduces weight, allowing spores to be carried by wind, water, or animals over vast distances with minimal energy expenditure. For instance, a single cubic meter of air can contain thousands of fungal spores, highlighting their efficiency in reaching new habitats.

Consider the shape of these spores—often spherical, elliptical, or filamentous—which further enhances their dispersal capabilities. Spherical spores, like those of many fungi, minimize air resistance, enabling them to travel farther in wind currents. Plant spores, such as those from ferns, often have intricate wing-like structures or ridges that increase surface area, aiding in buoyancy and glide. These shapes are not arbitrary; they are evolutionary adaptations that maximize the chances of landing in a suitable environment for growth.

To illustrate, compare the spores of *Aspergillus* fungi and mosses. Both are lightweight and aerodynamically shaped, but their dispersal strategies differ slightly. Fungal spores are often released in large quantities, relying on sheer numbers to ensure some land in favorable conditions. Moss spores, while fewer in number, are encased in capsules that open only under specific humidity levels, ensuring release when conditions are optimal for germination. Despite these differences, the underlying principle remains: size and shape are tailored for efficient dispersal.

Practical applications of this knowledge abound. For gardeners, understanding spore size and shape can inform strategies for controlling fungal or plant growth. For example, using fine mesh screens (with pores smaller than 100 micrometers) can reduce spore infiltration in greenhouses. Similarly, knowing that spores are lightweight and wind-dispersed can guide the timing of planting or fungicide application to minimize exposure. Even in medicine, the size of fungal spores is critical; their small diameter allows them to penetrate deep into the respiratory system, making them a concern for immunocompromised individuals.

In conclusion, the size and shape of fungal and plant spores are masterclasses in biological engineering. Their tiny, lightweight designs are not just coincidental but are finely tuned for survival and propagation. By studying these structures, we gain insights into nature’s ingenuity and practical tools for managing ecosystems, agriculture, and health. Whether you’re a scientist, gardener, or simply curious, appreciating these microscopic marvels reveals the elegance of life’s smallest units.

Can You See Spores in Spore Syringes? A Microscopic Look

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Both fungal spores and plant spores serve as reproductive structures, allowing the organisms to disperse and colonize new environments. They are essential for survival, propagation, and adaptation to different conditions.

Both types of spores are typically lightweight and small, which aids in wind or water dispersal. They also often have protective outer layers (e.g., cell walls) to withstand harsh environmental conditions.

Both rely on external agents like wind, water, or animals for dispersal. This passive dispersal mechanism ensures wide distribution and increases the chances of finding suitable habitats for growth.