Fungal spores and bacterial spores, while both serving as survival structures for their respective organisms, differ significantly in structure, function, and resistance mechanisms. Fungal spores, such as those produced by molds and yeasts, are typically multicellular, larger in size, and often have complex cell walls composed of chitin, making them more resilient to environmental stresses like desiccation and UV radiation. They are primarily reproductive structures, aiding in dispersal and colonization of new habitats. In contrast, bacterial spores, exemplified by those of *Bacillus* and *Clostridium*, are unicellular, highly resistant dormant forms produced in response to adverse conditions. These spores have a thick, multilayered coat and a dehydrated cytoplasm, enabling them to withstand extreme conditions such as heat, radiation, and chemicals for extended periods. While fungal spores are more about propagation, bacterial spores are specialized for long-term survival, highlighting their distinct evolutionary adaptations to environmental challenges.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Size | Fungal spores are generally larger (typically 1-100 µm) compared to bacterial spores (typically 0.5-5 µm). |

| Structure | Fungal spores are often multicellular or have complex structures (e.g., hyphae, asci, basidiospores), while bacterial spores are unicellular and simpler in structure. |

| Cell Wall Composition | Fungal spores have cell walls primarily composed of chitin, while bacterial spores have cell walls made of peptidoglycan. |

| Resistance | Fungal spores are less resistant to heat, desiccation, and chemicals compared to bacterial spores, which are highly resistant due to their thick, impermeable spore coats. |

| Reproduction | Fungal spores are typically produced through sexual or asexual reproduction (e.g., conidia, sporangiospores), whereas bacterial spores are formed through a process called sporulation as a survival mechanism. |

| Metabolism | Fungal spores are metabolically inactive but can germinate under favorable conditions, while bacterial spores are dormant and require specific triggers to return to active growth. |

| Shape and Morphology | Fungal spores exhibit diverse shapes (e.g., oval, filamentous, multicellular) and often have distinctive features like appendages or pigments. Bacterial spores are usually spherical or oval with a more uniform appearance. |

| Germination Time | Fungal spores generally germinate faster (hours to days) under suitable conditions, while bacterial spores may take longer (days to weeks) to activate and germinate. |

| Environmental Tolerance | Fungal spores are more sensitive to environmental stressors but can survive in a wider range of habitats. Bacterial spores are extremely tolerant of harsh conditions (e.g., extreme temperatures, radiation). |

| Genetic Material | Fungal spores contain a nucleus with eukaryotic genetic material (DNA with histones), while bacterial spores contain prokaryotic genetic material (circular DNA without histones). |

| Dispersal Mechanisms | Fungal spores are often dispersed via air, water, or animals and may have specialized structures for dispersal. Bacterial spores are primarily dispersed through air, water, or soil and lack specialized dispersal mechanisms. |

| Antimicrobial Susceptibility | Fungal spores are generally less susceptible to antibiotics but more susceptible to antifungal agents. Bacterial spores are resistant to most antibiotics but can be killed by specific spore-targeting agents (e.g., heat, chemicals). |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Cell Wall Composition: Fungal spores have chitin; bacterial spores lack chitin, containing peptidoglycan instead

- Resistance Mechanisms: Fungal spores resist desiccation; bacterial spores survive extreme heat, radiation, and chemicals

- Size and Shape: Fungal spores are larger and diverse; bacterial spores are smaller, oval, and uniform

- Reproduction Method: Fungal spores form via meiosis; bacterial spores form via binary fission (endospores)

- Metabolic Activity: Fungal spores remain metabolically active; bacterial spores are dormant until favorable conditions

Cell Wall Composition: Fungal spores have chitin; bacterial spores lack chitin, containing peptidoglycan instead

Fungal and bacterial spores, though both resilient structures, differ fundamentally in their cell wall composition. Fungal spores are fortified with chitin, a tough, nitrogen-containing polysaccharide also found in insect exoskeletons and crustacean shells. This chitinous layer provides structural integrity and protects the spore from environmental stressors like desiccation and predation. In contrast, bacterial spores lack chitin entirely. Instead, their cell walls are composed primarily of peptidoglycan, a complex polymer of sugars and amino acids that forms a robust mesh-like structure. This distinction in composition is not merely academic; it has profound implications for how these spores interact with their environment and respond to antimicrobial agents.

Consider the practical implications of this difference in a laboratory or clinical setting. Chitin, being unique to fungi and certain animals, is a target for antifungal drugs like chitin synthesis inhibitors. These compounds disrupt chitin production, effectively weakening fungal cell walls and spores. For example, nikkomycin and polyoxin are antifungal agents that specifically target chitin synthesis, making them effective against fungal infections but useless against bacteria. Conversely, bacterial spores, with their peptidoglycan-rich walls, are susceptible to antibiotics like penicillin and vancomycin, which interfere with peptidoglycan synthesis. Understanding this compositional difference allows researchers and clinicians to tailor treatments more effectively, ensuring that the right antimicrobial agent is used for the right pathogen.

From a structural perspective, the presence of chitin in fungal spores contributes to their rigidity and durability. Chitin’s β-1,4-linked *N*-acetylglucosamine units form a crystalline structure that resists mechanical stress and enzymatic degradation. This makes fungal spores particularly hardy, capable of surviving extreme conditions such as heat, cold, and UV radiation. Bacterial spores, while equally resilient, owe their toughness to the layered structure of their peptidoglycan-rich cortex and the additional protective layers, such as the spore coat. However, the absence of chitin in bacterial spores means they lack the specific mechanical properties conferred by this polymer, highlighting a key evolutionary divergence in spore design.

For those working in agriculture or food preservation, this compositional difference is critical. Fungal spores, with their chitinous walls, are more resistant to physical and chemical treatments like heat pasteurization and fungicides. For instance, sorbic acid, a common food preservative, inhibits fungal growth by disrupting chitin synthesis, but it has little effect on bacterial spores. Conversely, bacterial spores require more aggressive treatments, such as high-temperature sterilization (e.g., 121°C for 15 minutes in autoclaving) or specific antimicrobial agents like lysozyme, which degrades peptidoglycan. This knowledge informs the development of targeted preservation methods, ensuring that both fungal and bacterial contaminants are effectively controlled in various industries.

In summary, the cell wall composition of fungal and bacterial spores—chitin versus peptidoglycan—is a defining feature with far-reaching implications. It dictates their susceptibility to specific antimicrobial agents, their structural properties, and their resistance to environmental challenges. By understanding this difference, professionals across fields from medicine to agriculture can devise more precise and effective strategies for managing these microscopic survivalists. Whether designing antifungal drugs, preserving food, or studying microbial ecology, this compositional distinction is a cornerstone of practical and theoretical advancements.

Can You Play Spore on Aspire ES1-111M? Compatibility Guide

You may want to see also

Resistance Mechanisms: Fungal spores resist desiccation; bacterial spores survive extreme heat, radiation, and chemicals

Fungal spores and bacterial spores have evolved distinct resistance mechanisms to endure harsh environmental conditions, reflecting their unique ecological niches and survival strategies. Fungal spores excel at resisting desiccation, a critical adaptation for surviving in dry environments. Their cell walls, rich in chitin and glucans, provide a robust barrier against water loss, while internal compounds like trehalose act as protectants by stabilizing cellular structures during dehydration. This desiccation resistance allows fungal spores to persist in soil, air, and on surfaces for extended periods, often years, until conditions become favorable for germination.

In contrast, bacterial spores are masters of surviving extreme heat, radiation, and chemicals, making them among the most resilient life forms on Earth. Their resistance is attributed to a multi-layered protective coat, including a thick spore coat and a cortex rich in peptidoglycan, which provides structural integrity and acts as a barrier to toxins. Additionally, bacterial spores contain high levels of calcium dipicolinate and small acid-soluble proteins (SASPs) that protect DNA from heat, UV radiation, and chemical damage. For example, *Bacillus subtilis* spores can withstand temperatures exceeding 100°C for hours and exposure to hydrogen peroxide at concentrations up to 10% without losing viability.

To illustrate the practical implications, consider the food industry, where bacterial spores pose a significant challenge in sterilization processes. While fungal spores are effectively controlled by desiccation methods like dry heat (e.g., 170°C for 2 hours), bacterial spores require more aggressive treatments, such as autoclaving at 121°C for 15–20 minutes or exposure to gamma radiation at doses of 10–40 kGy. This highlights the need for tailored approaches when targeting these spores in different contexts.

From a comparative perspective, the resistance mechanisms of fungal and bacterial spores reflect their evolutionary trajectories. Fungi, being eukaryotic, have developed strategies to thrive in diverse environments by focusing on desiccation resistance, which aligns with their role in nutrient cycling and decomposition. Bacteria, being prokaryotic and often free-living, have prioritized survival in extreme conditions, including those found in hot springs, deep-sea vents, and radioactive environments. This divergence underscores the principle that survival strategies are shaped by the specific challenges organisms face in their habitats.

In practical terms, understanding these resistance mechanisms is crucial for industries ranging from agriculture to healthcare. For instance, controlling fungal spores in stored grains can be achieved through humidity management, while bacterial spores in medical equipment require high-temperature sterilization. By leveraging this knowledge, we can develop more effective strategies to combat spoilage, infection, and contamination, ensuring safety and efficiency in various applications.

Do Spore Syringes Expire? Shelf Life and Storage Tips

You may want to see also

Size and Shape: Fungal spores are larger and diverse; bacterial spores are smaller, oval, and uniform

Fungal spores and bacterial spores, though both reproductive structures, exhibit striking differences in size and shape that reflect their distinct evolutionary strategies. Fungal spores are generally larger, often measuring between 5 to 20 micrometers in diameter, and display a remarkable diversity in morphology. They can be round, oval, cylindrical, or even intricately sculptured, depending on the fungal species. This variability is linked to their role in dispersal and survival in diverse environments, from air to soil. In contrast, bacterial spores are significantly smaller, typically ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 micrometers, and maintain a consistent oval or elliptical shape. This uniformity is a hallmark of bacterial spores, optimized for resilience and efficient dispersal in harsh conditions.

Consider the practical implications of these size and shape differences. For instance, in laboratory settings, fungal spores are easily visible under a light microscope at 400x magnification, while bacterial spores require higher magnification or staining techniques like the Schaeffer-Fulton stain to be clearly observed. This distinction is crucial for microbiologists identifying contaminants or studying microbial communities. Additionally, the larger size of fungal spores makes them more susceptible to physical filtration methods, such as HEPA filters, which are commonly used in HVAC systems to control indoor air quality. Bacterial spores, due to their smaller size, can more easily bypass such filters, necessitating additional sterilization methods like autoclaving.

From an ecological perspective, the size and shape of fungal spores contribute to their dispersal mechanisms. Larger, diverse spores are often adapted for wind dispersal, with structures like wings or ridges that increase surface area and reduce settling velocity. For example, the spores of *Aspergillus* fungi have a distinctive star-like shape that aids in air travel. Bacterial spores, on the other hand, rely on their small size and uniform shape to remain suspended in air or water for extended periods, increasing their chances of colonizing new environments. This difference highlights how microbial spores are finely tuned to their ecological niches, with size and shape playing pivotal roles in survival and propagation.

For those working in industries like food preservation or pharmaceuticals, understanding these differences is essential. Fungal spores, due to their larger size, are more easily removed during physical processing steps like sieving or centrifugation. However, their resilience to heat and chemicals often requires more aggressive sterilization methods, such as exposure to temperatures above 121°C for 15–30 minutes in an autoclave. Bacterial spores, while smaller and more uniform, are notoriously resistant to environmental stresses, necessitating specific protocols like the use of sporicides (e.g., hydrogen peroxide or peracetic acid) to ensure complete eradication. This knowledge informs the design of effective sterilization processes tailored to the unique characteristics of each spore type.

In summary, the size and shape of fungal and bacterial spores are not arbitrary traits but reflect their distinct biological roles and environmental adaptations. Fungal spores leverage their larger size and morphological diversity for efficient dispersal and survival, while bacterial spores prioritize uniformity and compactness for resilience. Whether in a laboratory, industrial setting, or natural ecosystem, recognizing these differences is key to managing microbial contamination, studying microbial ecology, or developing targeted sterilization methods. By focusing on these specific traits, one gains a deeper appreciation for the intricate ways in which microorganisms have evolved to thrive in their respective environments.

Does Milky Spore Harm Beneficial Grubs in Your Lawn?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Reproduction Method: Fungal spores form via meiosis; bacterial spores form via binary fission (endospores)

Fungal and bacterial spores, though both survival structures, arise from fundamentally different reproductive processes. Fungal spores are the product of meiosis, a sexual or asexual process involving genetic recombination. This mechanism ensures genetic diversity, allowing fungi to adapt to changing environments. For instance, the common bread mold *Rhizopus stolonifer* produces spores through meiosis, enabling it to thrive in various conditions, from damp kitchens to decaying fruit. In contrast, bacterial spores, specifically endospores, form through binary fission, a type of asexual reproduction where a single cell divides into two identical daughter cells. This process lacks genetic recombination, resulting in spores that are genetically identical to the parent bacterium. *Bacillus subtilis*, a soil bacterium, exemplifies this, forming endospores that can withstand extreme conditions like heat and desiccation without altering their genetic makeup.

Understanding these reproductive methods is crucial for practical applications. For instance, in agriculture, fungal spores’ genetic diversity can be harnessed to develop disease-resistant crop strains. By selecting spores with beneficial traits, farmers can cultivate plants better equipped to fend off pathogens. Conversely, the predictability of bacterial endospores makes them ideal targets for sterilization processes. In healthcare, autoclaves use high-pressure steam (121°C for 15–20 minutes) to kill endospores, ensuring surgical instruments are free from contamination. This knowledge also informs food preservation techniques, where understanding spore formation helps in designing effective canning and pasteurization methods.

From a comparative standpoint, the reproductive strategies of fungal and bacterial spores highlight their evolutionary adaptations. Meiosis in fungi promotes survival through diversity, a key advantage in unpredictable environments. Bacterial binary fission, however, prioritizes efficiency and rapid proliferation, allowing bacteria to dominate stable but resource-rich habitats. For example, fungal spores’ ability to disperse widely and colonize new niches explains their prevalence in ecosystems ranging from forests to human lungs. Bacterial endospores, on the other hand, excel in persistence, surviving for centuries in harsh conditions until favorable conditions return. This contrast underscores the importance of tailoring control strategies to the specific reproductive mechanism of each organism.

To leverage this knowledge effectively, consider these practical tips. When dealing with fungal infestations, rotate fungicides to target spores with varying genetic resistances. For bacterial contamination, focus on eliminating endospores through heat or chemical treatments, as their uniform genetic structure makes them vulnerable to targeted interventions. In laboratory settings, differentiate between fungal and bacterial spores using staining techniques like calcofluor white for fungi and Schaeffer-Fulton for endospores. By recognizing the reproductive methods behind these spores, you can implement more precise and effective strategies for control, prevention, and utilization in both scientific and everyday contexts.

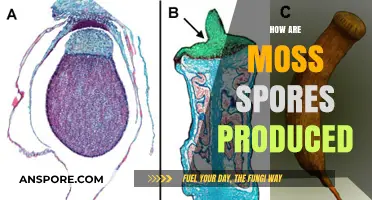

Do Sporophytes Produce Spores? Unraveling the Role in Plant Reproduction

You may want to see also

Metabolic Activity: Fungal spores remain metabolically active; bacterial spores are dormant until favorable conditions

Fungal spores maintain a low but detectable level of metabolic activity, enabling them to respond swiftly to environmental changes. Unlike bacterial spores, which enter a state of dormancy akin to suspended animation, fungal spores continue processes like respiration and enzyme production. This metabolic persistence allows fungal spores to germinate rapidly when conditions improve, often within hours. For instance, *Aspergillus* spores can initiate growth almost immediately upon landing on a nutrient-rich substrate, a trait exploited in industrial fermentation processes where quick colonization is essential.

Consider the practical implications for controlling fungal growth in indoor environments. Since fungal spores remain metabolically active, they can utilize minimal moisture and nutrients to survive and proliferate. This explains why mold appears so quickly in damp areas—the spores are already primed for growth. To prevent this, maintain indoor humidity below 60% and address water leaks promptly. Unlike bacterial spores, which require rehydration and nutrient availability to "wake up," fungal spores only need slight improvements in their surroundings to thrive.

From a comparative standpoint, the metabolic activity of fungal spores versus the dormancy of bacterial spores highlights their evolutionary strategies. Bacterial spores, such as those of *Clostridium botulinum*, are designed for long-term survival in harsh conditions, remaining inert until triggered by specific factors like temperature and pH. Fungal spores, however, prioritize readiness over endurance, sacrificing longevity for rapid response. This distinction is critical in medical and industrial settings: bacterial spores require extreme measures like autoclaving (121°C for 15–20 minutes) for eradication, while fungal spores can often be controlled with less aggressive methods, such as 70% ethanol or quaternary ammonium compounds.

For those working in agriculture or food preservation, understanding this metabolic difference is key to effective spore management. Fungal spores’ active state means they can germinate even in suboptimal conditions, leading to spoilage or disease. For example, *Penicillium* spores on bread can sprout at refrigerator temperatures (4°C), though slowly. In contrast, bacterial spores like *Bacillus subtilis* remain dormant until exposed to heat and moisture, a principle utilized in canning processes where food is heated to 100°C to destroy vegetative cells while spores remain viable but inactive. Tailoring strategies to the spore type—whether targeting active fungal spores or dormant bacterial ones—ensures more precise and efficient control.

UV Lamp Air Purifiers: Effective Mold Spores Killers or Myth?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Fungal spores are typically multicellular or have complex structures, often produced externally on specialized structures like hyphae or fruiting bodies. Bacterial spores, in contrast, are single-celled, highly resistant endospores formed internally within the bacterial cell.

Fungal spores are generally more resistant to desiccation and can survive in harsh environments, but they are less heat-resistant compared to bacterial spores. Bacterial spores are extremely heat-resistant and can withstand high temperatures, radiation, and chemicals.

Fungal spores primarily serve as a means of reproduction and dispersal, allowing fungi to colonize new environments. Bacterial spores are primarily a survival mechanism, enabling bacteria to endure unfavorable conditions until more suitable environments are available.

Fungal spores are formed through processes like meiosis or mitosis, often involving specialized structures like sporangia or asci. Bacterial spores are formed through a process called sporulation, where a single bacterial cell divides internally to create a highly resistant endospore.

Fungal spores vary widely in size and shape, depending on the fungal species, and can range from microscopic to visible to the naked eye. Bacterial spores are generally smaller, uniform in size, and oval or spherical in shape.